Ethel Wilson's Swamp Angel (Macmillan, 1954)

Part I: Swamp Angel—an Introduction

Publication and Reception

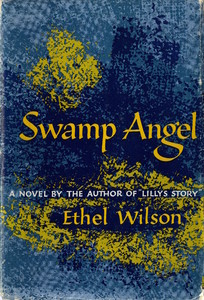

In 1954, with the support of Macmillan Canada, Vancouver author Ethel Wilson published her fourth and most recognizable work of fiction, Swamp Angel—a relatively short but deeply reflective novel about divorce, autonomy, the difficulties and rewards of starting over, and, more broadly, the enigma of human nature and relationships. Set, initially, in the city of Vancouver, the novel records the journey of the middle-aged widow Maggie Vardoe as she leaves an unhappy second marriage and finds work managing a fishing lodge in the British Columbian interior. Starting over with a new community of people who, though an improvement on her needy second-husband, require patience and careful management, Maggie grows in independence and compassion and holds the lodge together on the strength of her integrity and self-awareness. An outlier in terms of 1950s protagonists, the strikingly liberated figure of Maggie Vardoe is one of Wilson's most memorable contributions to Canadian Literature and a significant trailblazer for similarly empowered heroines to come.

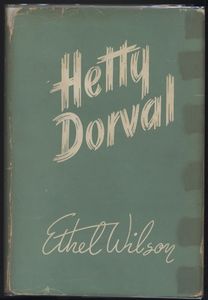

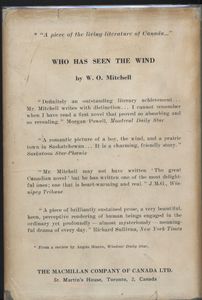

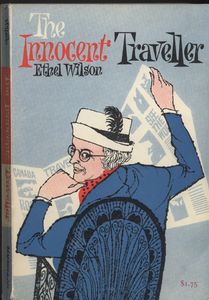

Today, Swamp Angel is widely regarded among Wilson scholars as the author's most philosophically and stylistically accomplished work—historically, however, both popular and critical appreciation for the novel has waxed and waned. When, for example, the book emerged in August of 1954, it did so to mixed reviews. Where some reviewers, such as William Arthur Deacon, lauded Swamp Angel as a “first-rate book” (qtd. in Stouck, Ethel Wilson: A Critical Biography 193), others found it short, lacking in plot and character development, and, because of its reflective nature, inaccessible. Due in part to its formal ambiguity and philosophically complex content, opinions have typically been drawn according to scholarly and non-scholarly lines. Wilson’s biographer, David Stouck, for example, notes that unlike Wilson’s previous three novels (Hetty Dorval [1947], The Innocent Traveller [1948], and The Equations of Love [1952]), Swamp Angel “did not have as much immediate appeal to general readers” (194), while academics have tended, over the years, to find “much of interest” (194) in this novel because of its ambiguity, the way it plays with form, and, since the 1970s, its early depiction of women’s rights issues.

Despite a respectable level of critical success, however, Swamp Angel is still relatively unknown outside of Canadian Literature Departments and, even then, is rarely taught as a core text in Canadian Literature courses. This oversight may have something to do with the fact that Swamp Angel has been notoriously difficult to categorize into any one genre and is, I suspect, overlooked in an effort to select books that are representative examples of definitive literary movements. Written during a distinctly modernist period in Canada’s literary history, Swamp Angel exhibits few of the formal features typically associated with Canadian modernism. And while it is more accurately labeled a “realist” novel, even this descriptor is complicated by poetic or romantic descriptions of place and moments of philosophical speculations that leave us, as Stouck suggests, “with a set of opposing patterns” (202). Certainly, a cursory reading of any number of Wilson’s novels will demonstrate that she is not afraid to interweave and hold in tension multiple literary, religious, and political points of view—a literary strategy concomitant with her personal belief that the world was a series of irreconcilable paradoxes. Thus, throughout Swamp Angel, a kind of proto-feminism is held in tension with a more conservative set of Christian humanist beliefs, realism appears at odds with the book’s metaphysical commentary, pagan mythological symbols emerge alongside religious ones, and the list goes on. As the book’s initial reception suggests, these paradoxes and tensions are what have made the book both “popularly unpopular” and critically interesting—they are also what make this novel such a fascinating and rewarding read.

Best Laid Plans

This page is therefore, in part, an opportunity to bring Ethel Wilson back into the “critical limelight." It is also, however, an attempt to place Wilson within a particular socio-historical context—namely, the writing and publishing arena of mid-twentieth-century Canada (what author Roy Macskimming aptly deems “the perilous trade”).

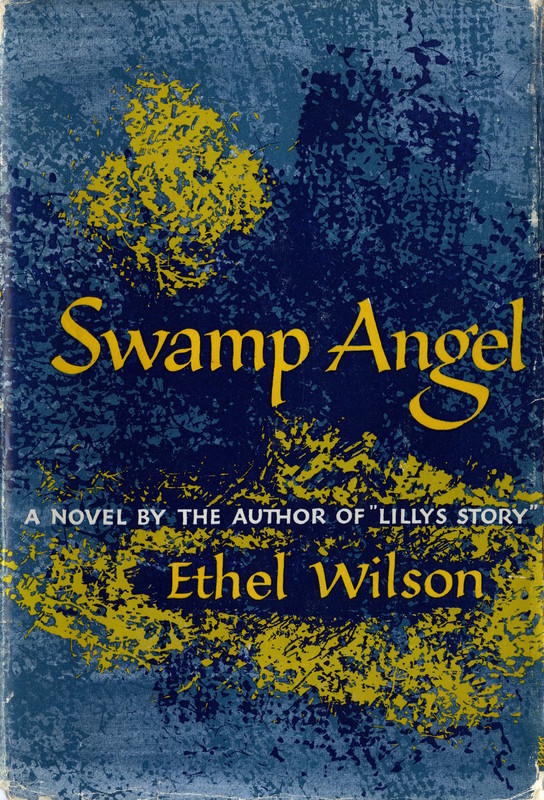

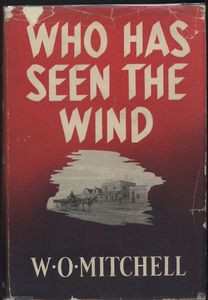

Swamp Angel makes for an intriguing case study in Canadian publishing for a number of reasons—the first of which being that there were actually two versions of the novel, one a Canadian edition published by Macmillan and the other American published by Harper and Brothers, released in the same year. Where the Canadian edition was published first, the American edition contains two additional chapters that Wilson added when her publisher at Harpers suggested that some of the book’s supporting characters appeared underdeveloped. For her part, Wilson agreed and, ultimately, vastly preferred the American edition—not just the text but also the overall aesthetic of the book itself, which “she felt . . . had more distinction than Macmillan’s” (Stouck 192).

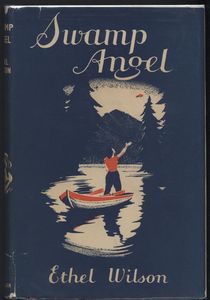

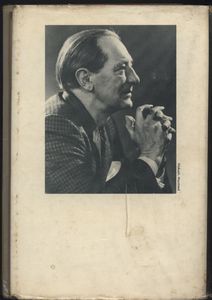

This particular iteration (see Figure #1.2), signed by the author and beautifully preserved in the University of Victoria’s Special Collections Department, is of the “Canadian variety” and is, as such, an opportune point of inquiry for a discussion on the nature of “the Text” and “Authorship” as definitive but practically fluid categories. Given Wilson’s comments on the novel’s “dressings” and aesthetic presence—and, indeed, the complex relationship between an author and his/her publisher as well as the omnipresent influence of economy in publishing more generally—one might wonder, for example, how much control Wilson had over the way her books were marketed and produced. Did she approve the cover art, the author’s blurb, and/or the photo that appears on the back cover? If not, why not? Why is it that the “text” begins and ends with the narrative? To what extent is the book’s wrapping (its dust jacket) an extension of the text? What role, if any, did Wilson’s gender play in the publishing and marketing of her book? The following three sections will attempt to contextualize and answer some of these questions, while providing insight into Ethel Wilson as a woman and an author, a wife and a professional, and, in particular, a female professional involved in the precarious and male-dominated world of publishing in 1950s Canada.

Malkin Family Outdoor Tea (Ethel Wilson - Back row, 6th from left)

Ethel Wilson - Author Portrait, Swamp Angel (1954)

Part II: Ethel Wilson—The Accidental Author?

Just as red hair occurs from time to time in families, or big thumbs, there was a tendency in my father's family towards writing—never very much, nor very good, but certainly never very bad, because they were a critical lot.

Ethel Wilson, excerpted from a letter to Desmond Pacey (July 12, 1953)

This statement from Ethel Wilson is one among many appearing throughout her essays, talks, and correspondence, that illustrate what critics, and in particular Wilson’s biographer David Stouck, have recognized as the author’s dual-persona. Excerpted from a letter to Desmond Pacey, the critic who would later introduce the 1962 edition of Swamp Angel, this quote forms the beginning of Wilson’s response to Pacey’s request for an account of her artistic influences and theory of literature (among other things). What follows is a short description of Wilson’s childhood, an overview of her influences and a significant passage in which she comments on the nature of “Canadian writing”—a frequently debated topic in mid-Century Canada when authors and critics were scrutinizing the country's literary output and reflecting on the extent to which Canada could claim a "national" body of literature at all. The impression that Wilson gives in this portion of the letter is of a confident and self-aware writer highly engaged in her craft and community. At the same time—and in keeping with this introductory quotation—Wilson’s letter is punctuated with qualifiers that diminish her authority and give the paradoxical impression that she is an amateur—an accidental author, so-to-speak. After expressing her love for the “clear, un-lush, and un-loaded” English sentence, for example, Wilson declares, “That does not mean that I cannot make a fine and awful mess of writing—for there is usually a wide span between what one does and what one would desire to do” (Stouck, ed. Ethel Wilson: Stories, Essays, and Letters 184). And, indeed, this kind of double backing from Wilson is not unusual. Elsewhere, in a letter to her editor at Macmillan, John Gray, Wilson maintains:

I am forced to believe that “people” are interested in Lilly’s Story as a bit of work, and that perhaps it has taken its own small place. Isn’t it funny? You never can tell! It has now an entity.

Here Wilson seems surprised to find that her work is not just popular, but well-regarded as a significant “bit of work”—despite the fact that discussions were, at this time, underway to turn Lilly’s Story into a film. Wilson, furthermore, could not let even this small admission of success stand without attempting to mediate Gray’s expectations with respect to her next project, Swamp Angel, subsequently urging Gray not to "expect too much" of her new work. "I cannot," she writes shortly after, "do what Walter Scott called 'The Big Bow Wow,' and would be a fool to try. I can only do my own things in my own way" (172). Comments like this are examples of what Misao Dean calls the “affected modesty” of early female authors who felt the need to cloak their authority with a kind of feminine restraint (Practising Femininity 6). Whether or not that reticence was the result of actual insecurity on Wilson’s part or a strategy she employed to avoid “making waves” in a male-dominated environment is impossible to tell—and, at the end of the day, as Dr. Dean suggested in conversation, even if the author were here and asked directly, she might lie.

Even so, Stouck’s biography sheds yet more light on Wilson’s dual persona in its overview of Wilson’s public assertions about herself as a writer and the somewhat different impression given in her letters and papers held at the University of British Columbia. Where, Stouck argues, Wilson presented herself in talks and interviews as a “doctor’s wife with a very full social calendar who, later in life, had a notion to write,” the Wilson Papers suggest that she was already working on The Innocent Traveller and sending work to major publishing houses in States as early as 1930 (Stouck, Ethel Wilson: A Critical Biography 78-79). Stouck also notes that, contrary to her suggestions otherwise, Wilson had never taken the “idea of writing” lightly, referring to her later admission that she was, to start, "frightened to take up a pencil" given what she felt was a lack of artistic consciousness on the West Coast (79). Like Wilson’s letter to Pacey, comments such as these suggest that Wilson was hardly the accidental and amateurish author she sometimes pretended to be, but, rather, a strategic and determined writer with a developed literary awareness.

The Significance of a Dual-Identity

What, you may ask, does Wilson’s so-called “dual-identity” have to do with texts like Swamp Angel, Hetty Dorval, and The Innocent Traveller—did not Barthe pronounce the author “dead”?! Since Barthe's infamous proclamation more and more scholars have begun to recognize the impossibility of doing away with the author and locating, beneath the contextual mire, a pure, unadulterated textual object. Seán Burke, for example, in his now classic text the Death and Return of the Author, makes an interesting case for the importance of authorship by demonstrating how attempts to theorize the author away have inadvertently placed the onus back on the author—alive or “dead” either the historical author or the specter of authorship ultimately factors into textual interpretation. In another insightful work on authorship, scholar Jack Stillinger probes the Barthean method of textual interpretation yet further by posing the question: When we think we have banished the author from his or her text, “how many authors” have we, in effect, banished (4)? For Stillinger, to ignore the “author” is to ignore a work’s collaborative history and feed into what he calls “the myth of solitary genius” (see Stillinger, Multiple Authorship and the Myth of Solitary Genius).

In the case of Swamp Angel, the contextual evidence provided by Wilson’s correspondence and essays, and a broader knowledge of the literary environment in which she wrote, can deepen our interpretation of her books as “texts” and as collaborative textual objects. At the most basic level, knowing Ethel Wilson’s gender, for example, can inform our reading of the Swamp Angel’s liberated heroine, Maggie Vardoe, as she comes to terms with her divorce and starts over in the male-dominated world of fly fishing and lodge-life. Knowing, moreover, something about Wilson’s perception of herself as an author and the ways in which she interacted with her editors, publishers, and even her reading public, may also aid in our interpretation of the book object itself as a collaborative project between Wilson, Macmillan, and John Gray—among others. The following two sections will thus explore Swamp Angel as a discursive product between Wilson the sometimes conflicted author, John Gray her longtime editor and friend, the Macmillan company, and, finally, the socio-cultural milieu of mid-century Canada.

Part III: Publishing in 1950s Canada — Ethel Wilson, John Gray, and the "Perilous Trade"

Publishing Canadian books has always been an experiment. Like the great experiments of building a transcontinental railway and a national broadcasting system, or the primal work of mapping our immense geography, it constitutes one of the nation’s defining acts. Publishing, after all, is a people’s way of telling its story to itself.

Roy Macskimming, The Perilous Trade

Since the mid-nineteenth century, critics, scholars, and authors have wondered at the paucity of Canadian literature in this country. “Why so few Canadian books? Why so little interest in the books that exist? Where are our authors?” some concerned party seemed, until recently, to ask every few years.[1] Though the answers to these questions vary slightly, the common denominator has typically been economy. Sandwiched between two, significantly larger, English-speaking nations (Britain and the United States), each with their own established literary traditions, nineteenth-century Canada was hardly an ideal environment for authors hoping to write for and about a Canadian audience, given that same audience was just as likely to purchase reprints of a Dickens, Austen, or Brontë novel or, later, the newest work from Hemmingway or Steinbeck. For these same reasons, publishing literature by Canadians for Canadians was (and is) an expensive enterprise that major publishing companies were reticent to take on—Until, that is, the early 1950s when editors at a few key houses became strategic about promoting Canadian writers.[2] Driven by a sense of moral obligation to, as Ruth Panofsky suggests, “foster” a “modern literature for Canada” ("The Macmillan Company of Canada"), editors such as Jack McClelland of McClelland & Stewart, Marsh Jeanneret of the University of Toronto Press, William Toye of Oxford University Press, and Ethel Wilson’s own editor John Gray of Macmillan, became foundational figures in what Roy Macskimming calls “the modern era” of Canadian publishing (2).

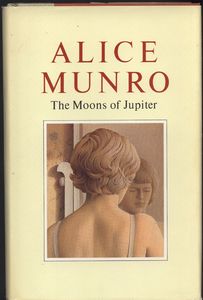

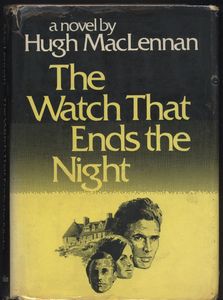

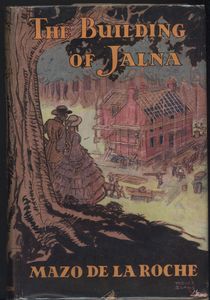

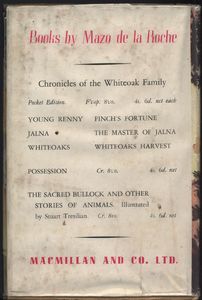

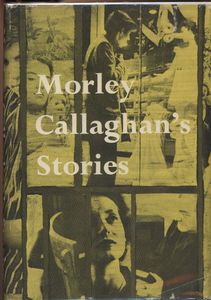

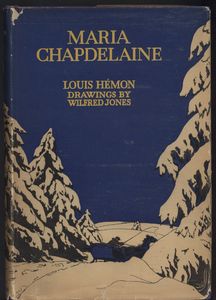

Gray in particular doggedly pursued both new and established talent to the extent that, by the 1950s, most of Canada’s leading fiction writers were publishing with Macmillan Canada. Over the course of his career at Macmillan, Gray was responsible for the success of famous names such as Morley Callaghan, Mazo de la Roche, Hugh MacLennan, and Robertson Davies. Gray was also well regarded within the industry not just for the books he published, but for the warm friendships he developed with authors such as Davies and, notably, Ethel Wilson. Having Gray as an ally in what was still a “perilous” and competitive market would have been to Wilson’s advantage and contributed to the success and/or failure of Swamp Angel. And, indeed, what their exchanges show is a kind of congenial editorial give and take undergirded by genuine affection. Responding, for example, to Wilson’s well-documented insecurities with regard to her Swamp Angel manuscript, Gray, in a letter dated August 4th, 1953, reassures Wilson:

How could you ever doubt again that your writing is good? . . . [J]ust know that we are eager to read you always, certain that even when we have suggestions to make, the reading will have been an illuminating and stimulating experience. (Qtd. in Stouck, ed. Ethel Wilson: Stories, Essays, and Letters 189)

Certainly, Gray’s faith in Wilson’s talent and Wilson’s affection for Gray are evidenced by the number of books the two published together—3 novels, 2 novellas, and a collection of short stories between 1947 and 1961.

[1] See, for example, William Arthur Deacon, “What a Canadian Has Done for Canada.” Poteen: A Pot-Pourri of Canadian Essays, Laurentian Press Syndicate, pp. 51–62; Northrop Frye, “Conclusion to a Literary History of Canada.” Literary History of Canada, edited by Carl F. Klinck, U of Toronto P, 1945, pp. 213–250; Desmond Pacey, “Religionalism and Nationalism.” Essays in Canadian Criticism, 1938–1968, Ryerson, 1969, pp. 159–165.

[2] Macskimming notes that while publishers have operated in Canada since the early 1800s, they were not necessarily publishing Canadian authors. There is, he maintains, “a basic distinction . . . between publishing Canadian books and publishing books in Canada” (2). Up until mid-twentieth century, most publishing houses (often transplants of British and American companies) in Canada simply re-printed and distributed American and British works.

A Tale of Two Texts: Macmillan Canada vs. Harper's (US)

The extent to which Wilson’s insecurities played into the drafting and subsequent revising of her manuscript of Swamp Angel is difficult to determine. Wilson’s literary philosophy is notoriously idiosyncratic—a self-professed lover of the English sentence, it was not unusual for her to stand her ground with regard to the placement of a comma, word choice, or rhythm, but eliminate entire characters at the bequest of her publishers (Dean, "I Just Love Ethel Wilson" 65; Stouck, Ethel Wilson: A Critical Biography 190). The novel began in 1951 as a short story called “Country Matters” that described “life in the Fraser delta region—the Chinese market gardens, the fishing boats on the river, the sawmills on shore” (Stouck 185)—and was later combined with two other stories (“Sweet Influence Doth Impart” and “The Swimmer”) to form the manuscript that would become Swamp Angel. The initial draft met with general approval, but some reservations. Readers at Macmillan felt that the “story was ‘slight’,” certain characters “boring” or “unbelievable,” and the novel lacking in drama and popular appeal. Though Gray shielded Wilson from some of the harsher criticisms, he nonetheless suggested that she cut back on scenic descriptions, prune her philosophical digressions, and alter the novel’s final scene, which had Maggie Vardoe symbolically relinquishing her Swamp Angel pistol to the lake. Recognising, based on Gray’s comments, that the book was “long on style and short on story” (Wilson qtd. in Stouck 187), Wilson ultimately shortened those sections of the text that readers found halting and excised most of the “Country Matters” material. She did, however, stick to her guns regarding the ending. What resulted was a slightly more streamlined novel, but one that was still, Wilson felt, problematically short. For whatever reason (the exact details are unknown), and in spite of his own concerns, John Gray decided to go ahead with publication and, in August of 1954, Swamp Angel made its way to the Canadian market.

Around the same time, Harper Brothers, the publishing house that had successfully released an American edition of Wilson’s novella Lilly’s Story, arranged to bring out an edition of Swamp Angel for the U.S. market. Unlike Macmillan, however, Harper’s pushed Wilson to lengthen the work and develop some of her secondary characters—a request to which Wilson readily acquiesced given her pre-existing misgivings about the book's length (Stouck, Ethel Wilson: A Critical Biography 192). The two chapters that Wilson ultimately added provided needed context and cohesion; however, by the time she was finished the Canadian edition had already gone to press (193). As a result, two similar but distinct editions of Swamp Angel were introduced to the North American market in the same year. Despite Wilson’s preference for this second version of the text, it was, unfortunately, the Macmillan version that was reprinted in 1962 and again in 1982 as part of McClelland & Stewart’s New Canadian Library series—a decision that testifies to the ever present pressures of speed and economy in Canadian publishing. Though the "death of the author" may be, as Sean Burke suggests, theoretically untenable, it is often a practical "given" in the perilous trade. Indeed, it was not until well after Wilson’s death that David Staines, the series editor for NCL, did his biographical homework and uncovered Wilson’s documented fondness for the Harper edition (Dean, Interview). To his lasting credit, when, in 1990, NCL moved to reprint Swamp Angel as part of Wilson’s Complete Works, Staines ensured that the American edition was used as the edition’s source text.

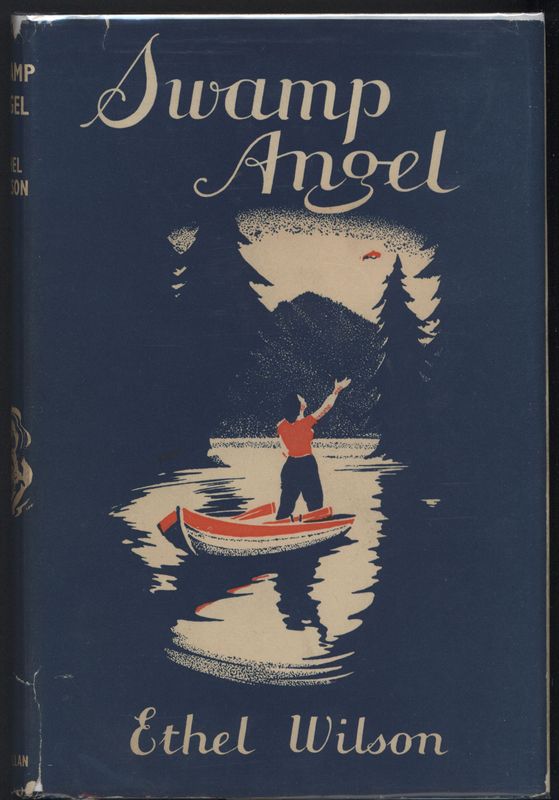

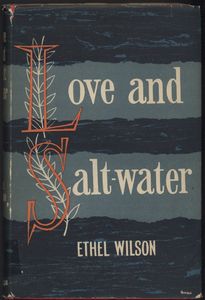

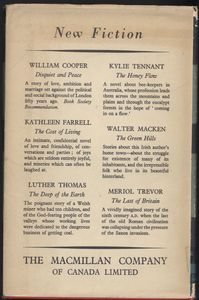

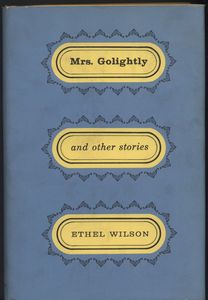

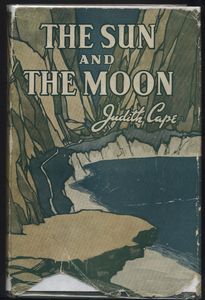

Figure #4.1 – Cover of Swamp Angel (Macmillan, 1954)

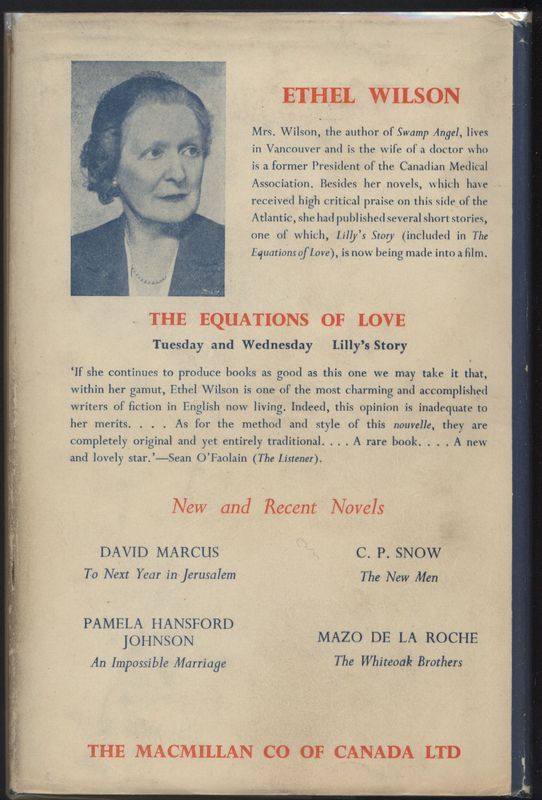

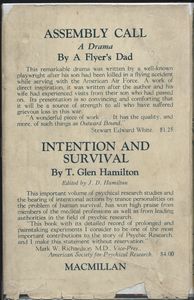

Figure #4.2 – Back Cover of Swamp Angel (Macmillan, 1954)

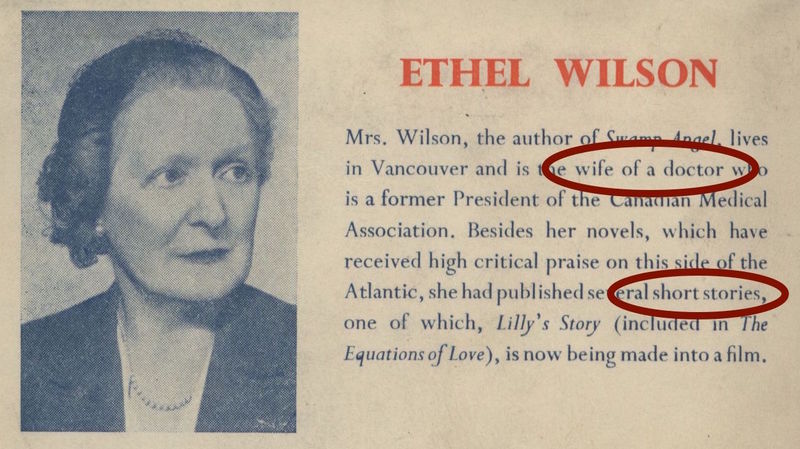

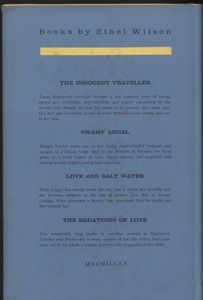

Figure #4.3 – Author Biography

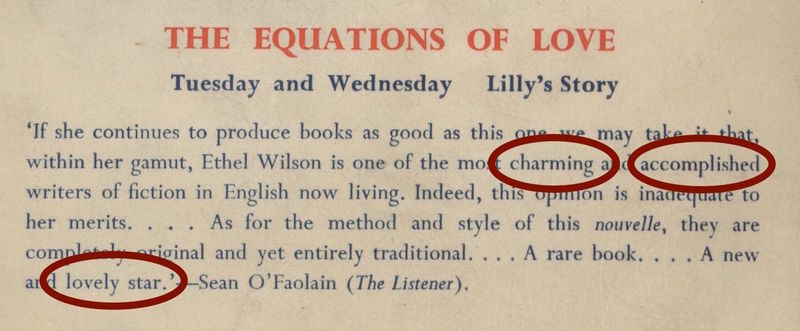

Figure #4.4 – Review of Wilson's Equations of Love

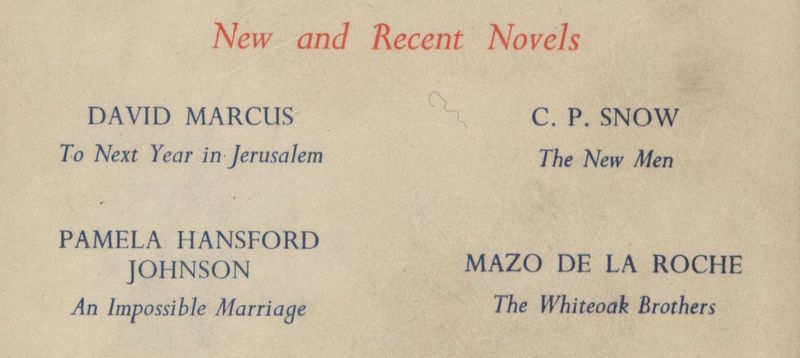

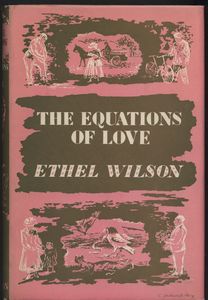

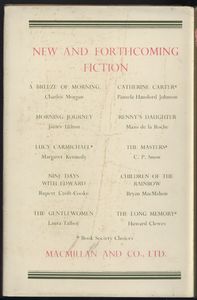

Figure #4.5 – Swamp Angel Adverts

Part IV: Swamp Angel—"The Book Stops Here..."

Judging a Book by its Cover: Or, What a Dust Jacket Has To Say About Women Writers in Twentieth-Century Canada

UVIC’s copy of the 1954 Macmillan edition is remarkably well-preserved. Though, as the image on the left indicates (see Figure #4.1), there is some wear and tear at the corners, given the delicacy of the book’s paper cover we are fortunate that some forward-thinking (anonymous) donor thought to preserve it at all. Too often, dust jackets like this one are discarded—particularly in large libraries where older texts are regularly rebound with sturdy, utilitarian covers—a shame given all that a book’s cover can tell us about the social and economic conditions in which the text emerged.

Taking a look at this particular jacket, for example, we can see that Ethel Wilson has been marketed in gender-specific ways. Her identity as an author is, in her biographical blurb, foregrounded by her identity as the wife of Wallace Wilson, the medical doctor—and, indeed, even her novels seem to take a back seat to her short stories, which were, at the time, considered a more “feminine” literary medium.[1] Slightly less obvious, but no less gender-specific, is the review Macmillan selected, which evaluates Ethel Wilson the person as being “charming,” “accomplished,” and “lovely” and her book as both “original” and “traditional.” With the exception of the word “original,” which is qualified, to some extent, by the word “traditional,” these are all terms that would have been (and still are) “coded” feminine and suggest the extent to which female authors were evaluated in light of their gender well into the twentieth century. Speaking to a similar phenomenon in nineteenth-century women’s poetry in Canada, Carole Gerson notes that the “literary qualities for which a woman poet was praised usually referred back to her gender. . . . Delicacy, beauty, simplicity, piety, purity, closeness to nature, were among the elements frequently lauded in nineteenth-century prefaces” (58). Based on the cover of Wilson’s Swamp Angel, it would seem that even in the 1950s little had changed in this regard.

The extent to which the book’s jacket and its content are at odds are a testament to the collaborative nature of not just Swamp Angel the text, but Swamp Angel the textual object—however, coherent or disjunctive this final product might be. For while it is unlikely that Wilson was given a chance to approve the book’s textual “wrappings,” readers of this or any copy of Wilson’s novel will consciously or unconsciously read the novel in light of its paratextual material.

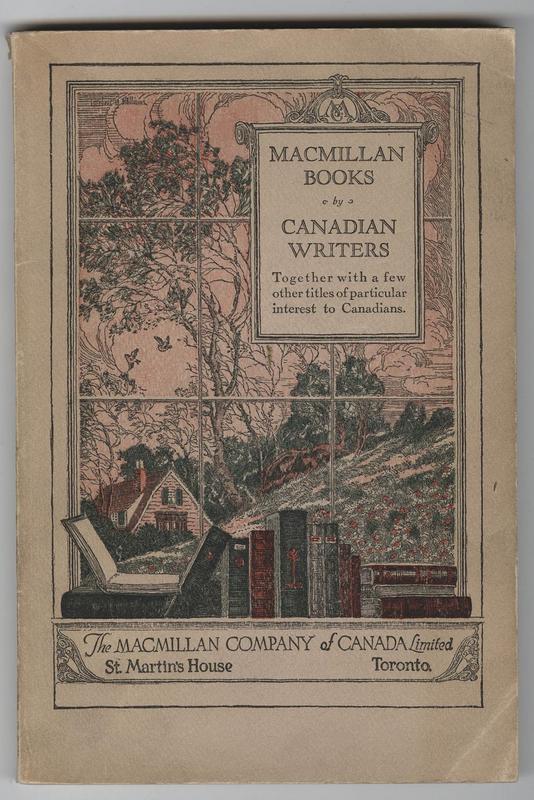

Canadian Women Writers—A Legacy Ill-defined

Interestingly, the advertisements listed on the Swamp Angel’s jacket suggests something different about “marketing” gender, given that Macmillan has attributed equal space to the promotion of “new and recent novels” by two male and two female authors—a surprising ratio in light of the fact that even in 1954 publications by male novelists vastly outnumbered those of their female counterparts. To be sure, this arrangement may simply have been Macmillan’s attempt to market their works as broadly as possible—at the same time, these adverts bear out what Carole Gerson demonstrates has been a historical tendency to misrepresent the number of women writing and publishing in Canada throughout the twentieth century. As early as 1899, for example, Canadian critic Laurence Burpee boasted that “in fiction, as in verse, Canadian women are marching apace with the members of the opposite sex” (Burpee qtd. in Gerson p. 193)—a claim that even well into the twentieth century was not statistically supportable. A brief look at the fiction section of Macmillan’s 1929 publication catalogue (see Figure #3.1) for example, which lists 28 novels authored by men and only 10 by women, attests to the inaccuracy of Burpee’s claim—however well meant.

Gerson attributes this phenomenon to our human tendency to confuse to visibility—or, in the case of early women authors, notoriety—with abundance, stating, in the conclusion to her book Canadian Women in Print, 1750–1918,

A potent explanation for this pattern appears in references to Samuel Johnson’s oft-cited comparison of a woman preacher to a dancing dog: ‘Sir, a woman preaching is like a dog’s walking on his hind legs. It is not done well; but you are surprised to find it done at all.’ . . . This unacknowledged sense of abnormality, I would argue, accounts for our distorted notion of the presence of women in Canada’s literary history. The few dogs teetering on their hind legs, above the many who stand normally on four, are briefly more visible and seem more abundant than their actual numbers. (195–196)

Bolstered, in recent decades, by the recuperation of Canadian authors like Sarah Jeanette Duncan, this “myth of abundance,” persists and is, Gerson argues, reified every time someone (be it a literary critic or interested reader) extols famous figures like Margaret Atwood or Alice Munro as the metonymic faces of contemporary Canadian literature. Even today, she insists, “achieving celebrity is not the same as enjoying canonicity” (196).

Ethel Wilson: A Legacy to Be Defined

What, if anything, does this distinction mean for an author like Ethel Wilson who seems to have enjoyed neither? Has Wilson been overlooked precisely because she is thought to be the lesser of the “many” women authors Canada has to offer? Since the 1970s, Wilson has reappeared from time to time as part of a (still ghettoised [see Gerson 196, 197]) canon of Canadian women writers, but is rarely discussed in relation to other “canons” or literary movements or, indeed, simply on the merit of her work as literature. In 1981 Wilson was the topic of a symposium series inaugurated by the University of Ottawa “as a means of directing attention . . . to Canadian authors meriting reassessment” (McMullen 1). Given the dearth of Wilson scholarship, however, the Wilson conference was, as Lorraine McMullen notes in her introduction to the published collection, “prompted by a desire for what might more properly be termed an assessment rather than a reassessment” (1). To its credit, the symposium gave rise to eleven excellent papers ranging from personal reflections on Wilson by those who knew her to scholarly presentations on Wilson’s literary technique, nascent feminism, and relation to other authors such as Edith Wharton and Willa Cather. Since then, several articles have been written that have drawn Wilson, and Swamp Angel in particular, back into the critical sphere—most notably, perhaps, Li-Ping Geng's account of the book's rival editions in 2002, which gave rise to a critical edition of Swamp Angel published by Tecumseh Press in 2005. Wilson’s “assessment,” however, is hardly finished. In his conclusion to the aforementioned conference volume, for example, Canadian scholar W. H. New suggests examining Wilson in terms of politics—both governmental and sexual—while David Stouck, in his assessment of Swamp Angel looks forward to ecocritical and/or bioregional readings of Wilson’s work. I myself was pleasantly surprised, just this year, to hear a colleague give a queer reading of Maggie's emotional and physical journey to the interior! Thus, while Wilson’s relative obscurity is a shame, it is also an invitation to contribute something new and exciting to a diverse range of critical conversations and, in so doing, shed light on a Canadian author well worth exploring.

[1] Carole Gerson notes, for example, that “[a]s the medium is inseparable from the message, the physical form in which an author’s words appear plays an important role in signalling their significance.” The book, because of its cultural and religious significance, is “historically a more masculine medium” as opposed to newspapers, magazines, or short stories, which, because of their supposed “ephemerality” were coded feminine (67).

Works Cited

Brown, E.K. On Canadian Poetry. Ryerson, 1943.

Burke, Seán. The Death and Return of the Author: Criticism and Subjectivity in Barthes, Foucault and Derrida. Edinburgh UP, 1998.

Deacon, William Arthur. “The Rise of Realism.” Canadian Novelists and the Novel, edited by Douglas Daymond and Leslie Monkman, Borealis, 1981, pp. 125–132.

———. “What a Canadian Has Done for Canada.” Poteen: A Pot-Pourri of Canadian Essays, Laurentian Press Syndicate, pp. 51–62.

Dean, Misao. “I Just Love Ethel Wilson: A Reparative Reading of The Innocent Traveller.” English Studies in Canada vol. 40, no. 2, 2014, pp. 65–81.

———. Personal Interview. 30 November 2016.

———. Practicing Femininity: Domestic Realism and the Performance of Gender in Early Canadian Fiction. U of Toronto P, 1998.

Frye, Northrop. “Conclusion to a Literary History of Canada.” Literary History of Canada, edited by Carl F. Klinck, U of Toronto P, 1945, pp. 213–250.

Geng, Li-Ping. "The Rival Editions of Ethel Wilson's Swamp Angel." Essays on Canadian Writing, no. 77, 2002, pp. 63–69.

Gerson, Carole. Canadian Women in Print 1750–1918. Wilfrid Laurier UP, 2010.

Macskimming, Roy. The Perilous Trade: Book Publishing in Canada, 1946–2006. McClelland & Stewart, 2007.

McMullen, Lorraine. Introduction. The Ethel Wilson Symposium, U of Ottawa P, 1982, pp. 1–5.

Pacey, Desmond. “Regionalism and Nationalism.” Essays in Canadian Criticism, 1938–1968 , Ryerson, 1969, pp. 159–165.

Panofsky, Ruth. The Literary Legacy of the Macmillan Company of Canada. U of Toronto P, 2012.

———. “The Macmillan Company of Canada.” Historical Perspectives on Canadian Publishing, http://hpcanpub.mcmaster.ca/case-study/macmillan-company-canada. Accessed 18 November 2016.

Stillinger, Jack. Multiple Authorship and the Myth of Solitary Genius. Oxford UP, 1991.

Stouck, David. Ethel Wilson: A Critical Biography. U of Toronto P, 2014.

Stouck, David, editor. Ethel Wilson: Stories, Essays, and Letters. U of British Columbia P, 1987.

For additional information on the history of book publishing (editors, illustrators, printing and publishing companies, etc.) in Canada see the following excellent articles and case studies online:

Garay, Kathy. “Marian Engel: A Life in Writing.” Historical Perspectives on Canadian Publishing, http://hpcanpub.mcmaster.ca/case-study/marian-engel-life-writing. Accessed 18 November 2016.

Kozakewich, Tobi. “Mazo de la Roche and the Atlantic Monthly Award.” Historical Perspectives on Canadian Publishing, http://hpcanpub.mcmaster.ca/case-study/mazo-de-la-roche-and-atlantic-monthly-award. Accessed 18 November 2016.

Lennox, John. “William Arthur Deacon: Reviewing, Advertising, and Publishers.” Historical Perspectives on Canadian Publishing, http://hpcanpub.mcmaster.ca/case-study/william-arthur-deacon-reviewing-advertising-and-publishers. Accessed 18 November 2016.

“Production (Design, Illustration, Technology).” Historical Perspective on Canadian Publishing, http://hpcanpub.mcmaster.ca/theme/production-design-illustration-technology. Accessed 18 November 2016.

Spadoni, Carl. “Publishers’ Catalogues and a Chariot on Yonge Street: Marketing Canadian Books.” Historical Perspectives on Canadian Publishing, http://hpcanpub.mcmaster.ca/case-study/publishers-catalogues-and-chariot-yonge-street-marketing-canadian-books. Accessed 18 November 2016.

NB/Fall2016

!["St Martin's House" - Home of Macmillan of Canada, [n.d.] "St Martin's House" - Home of Macmillan of Canada, [n.d.]](../../../../files/fullsize/d0ae8faad5b42ee9df97714aa076cc5d.jpg)

![[text] [text]](../../../../files/thumbnails/bf0153fd98ecf5298a4d8f9d853223f6.jpg)

![[Untitled] [Untitled]](../../../../files/thumbnails/8f7f2a548cb045ca08b3d486d164197a.jpg)