Kick it Over (1982-1994)

"THE PASSION FOR DESTRUCTION IS A CREATIVE PASSION, TOO."

- Mikhail Bakunin

Front cover of Kick it Over, Issue 34 - Food and Land issue.

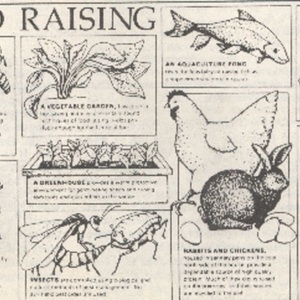

Radical Agriculture article in Kick it Over.

Food not Bombs slogan and logo.

The title of a permaculture article in Kick it Over.

DEFINING KICK IT OVER (1994)

Kick it Over is an anarchist magazine that was published between 1982 and 2004 by the anonymous, underground Kick it Over collective in Toronto, Canada. Kick it Over is a highly sophisticated, organized political tool of resistance employing multiple visual and literary art forms to appeal to, educate, and mobilize a wide variety of readers—from those with no knowledge of anarchism to anarchist-identifying academics or long-term members of the Canadian anarchist community.

Issue 34, the Food and Land issue, was selected for study due to its special emphasis on border issues, radical agriculture, food production, and sustainability, though articles in this issue also explore topics ranging from queer rights activism to anarchist summer camps. Of particular importance to this specific issue is permaculture, affectionately coined the “revolution disguised as gardening” (72) by anarchist James Heckert, who argues that permaculture is an ethical design system for food production that is both sustainable and self-sufficient.

Featured literary works representing the Food and Land issue’s main themes include:

- “Land Trusts: Land Held in Common”

- “Food not Bombs”

- “Permaculture: Focus on the Future”

- “Bread” (an anti-consumerist, anonymously contributed poem)

Noticeably absent from multiple artistic and literary contributions are author and artist names. While some are included, it is important to note that Kick it Over collective members remain unidentified in the magazine, and no official publication address is included. This veil of anonymity would have been a powerful tool protecting contributors from suspicion under government officials.

Despite the magazine’s longevity, many contributors and collective members will move through their lives without ever taking public credit or ownership for their artistic contributions.

Title pulled from within the first few pages of Kick it Over demonstrating anarchist spirit found in the magazine.

LET’S TALK ANARCHY

The International Encyclopedia of Political Science explains that anarchism is etymologically derived from two Ancient Greek words: αν, meaning “absence of,” and Aρχη′f, meaning “ruler” (73). In the most basic of terms, anarchism as a political philosophy denies all authority (Woodcock 11), or phrased more sharply, attacks authority as a fundamental principle in the construction of contemporary societal institutions. As such, argues renown anarchist scholar Jeff Shantz, anarchy “has formed the spectre that has haunted the dreamscapes of capitalist and statist authorities” (1) more so than any other political philosophy. Its implications are entirely dangerous to basic economic, political, and social structures contemporary society is built upon. Anarchism posits that systems of hierarchy, domination, and authoritarianism should be dismantled (Shantz 4). From an economic standpoint, anarchism asserts that integrated power systems like capitalism and consumerism represent forms of control and regulation over citizens (Shantz 5), and must destroyed. Anarchists believe that those eagerly participating in the capitalist, bourgeois civilization are enacting a systematization of power (Heckert 8) operating upon acquiescence of the masses.

So what would the Kick it Over collective members propose as social, political, and economic alternatives to contemporary institutions? Anarchists envision a society in which members possess their own means of production (Woodcock 21)— a society structured to afford all members autonomy, solidarity, and mutual help through social relations (Heckert 7). By freeing citizens from the shackles of authority and oppression, anarchism seeks to release members into a state of peace, justice and equality (Shantz 1).

A photograph of a Food not Bombs protest displaying to readers active resistance. The exact location and date of the photograph remains unknown.

SOCIAL, POLITICAL, AND HISTORICAL CONTEXT OF KICK IT OVER

Kick it Over, first published in 1982, draws its roots from the North American political and social turmoil of the 1950s and 1960s—influenced by the Vietnam War, Cold War (and coinciding calls for nuclear disarmament), student post-secondary revolts, the emergence of second wave feminism, and civil rights movements (Woodcock 387). Issue 34’s publication date of 1994 corresponds to the resurgence of North American anarchism seen in the early 1990s with alternative global justice movements. The 1990s, argues Shantz, brought to life young activists eagerly searching for alternatives to the exploitative and repressive structures of capitalism and hierarchical social organization they were born into (1). Considering this, Kick it Over is both a call to action and mapping of how to enact that political and social action. Anarchist scholar Jamie Heckert notes that:

“Bodies and bullets are real. Painfully real. The concrete does not self-organize into the Wall. No border, invented by human minds, asserts its own existence. No gun shoots itself. There is human action behind every border, every wall.” (72)

Of course, Kick it Over is as concerned with taking action as it is with inaction—political acquiescence and the intellectual sedentariness (Heckert 72) giving rise to it. Kick it Over is meant to stir affect within the placated reader as much as it is meant to stoke the rage of the ardent activist.

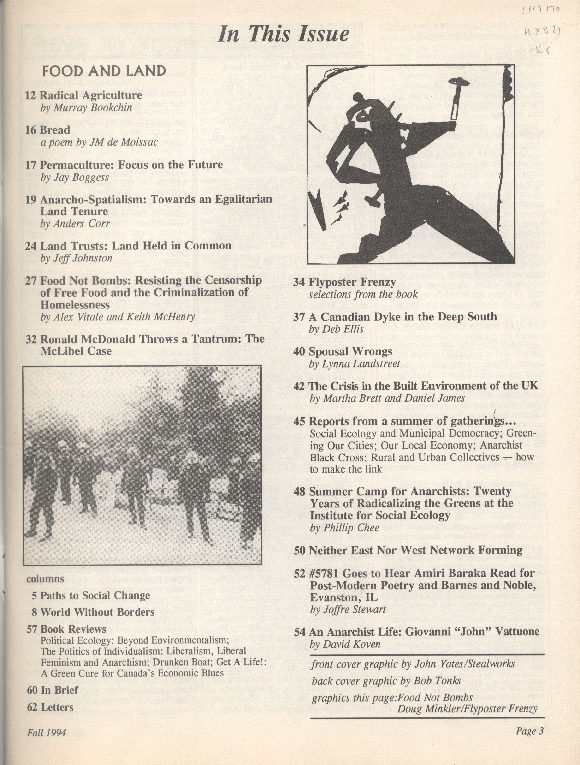

The neatly organized Table of Contents in Kick it Over.

Kick it Over's glossy, colorful back page adheres to the expected format of a magazine's exterior.

KICK IT OVER AS (RE)ACTION

Anarchism has historically been perceived by political and economic elites as threatening, and consequently, anarchism has been condemned by political elites who portray anarchism to be a “force of evil, chaos and harm” (Shantz 1). Contemporary anarchists are often represented in corporate media as political assassins or terrorists carrying forth the “inarticulate rage of the mob” (Shantz 1). Kick it Over would have been consciously produced with the highly attuned knowledge of anarchy’s unappealing reputation in contemporary society. As a result, the magazine stands as a reaction to skewed portrayals of anarchy—an effort to educate those unknowing in the readership. Kick it Over is, at the same time, a conformity to all of the basic features of a typical magazine—it has a glossy and colourful front cover, well-crafted and engaging articles employing humour and satire, and appealing graphics pepper the magazine. In this sense, Kick it Over’s historic struggle to present itself as apart from crass, base urges of the unrefined political agenda is more projected than anything else, and so is its insecurity at being perceived this way. The text must react to anarchy’s unflattering reputation by packaging itself as an organized, neatly presenting weapon. There are no angry tirades between these covers, no eschewing of page numbers or a table of contents—instead, there is a cogent effort to organize information presented in the magazine. Kick it Over is a careful political tool.

KICK IT OVER: ANARCHIST TEXTUAL CREATIVE RESISTANCE

Kick it Over is a piece of creative resistance—an art form, either literary, visual or a combination of both, that communicates the tenants of a political ideology or movement. In the words of Genevieve Lynes, creative resistance is akin to Jacques Derrida’s “teleopoeisis” which evokes both “the aesthetic act of imagining in advance and the political activism of being the change one wants to see in the world” (1). Anarchist creative resistance is concerned with the poesis element of literary production, or “imaginative making” (Lynes 1), and also with the destructive urges of anarchy. Anarchists accept the impulse to “end domination, to smash power over others, to destroy the means through which working people are robbed and exploited” (Heckert 8).

Forms of literary artwork ranges from long-form creative nonfiction (usually personal accounts of resistance), memoir/autobiography, poetry, and crafted anarchist book and poetry reviews.

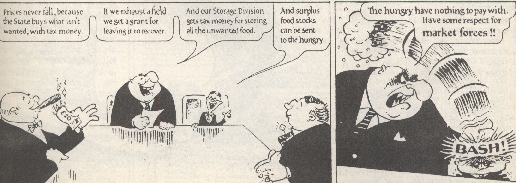

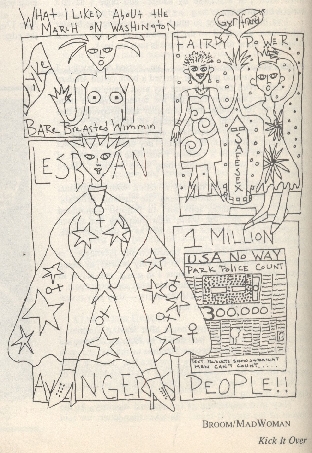

Forms of visual artwork included range from hand-drawn diagrams, anti-capitalist political cartoons, computer designed graphics, and photographs taken on scene at rallies.

The multiplicity of artistic forms presented in Kick it Over demonstrate anarchism’s enthusiastic experimentation with form and subject matter. This scattered, eclectic array of artistic forms is symbolic of anarchy’s essence—in keeping with anarchist poet Lucian Gregory’s philosophy, Kick it Over presents “the lawlessness of art, the art of lawlessness”(Shantz 14). It is an art form which rejects certain ordering principles of text and subject matter that conventional publications abide by.

ANARCHO-POESIS AND CREATIVE RESISTANCE

“Authors are constructive, abrasive, some like a sort of punk rock

whetstone sharpening a prod to society, [with] many sparks to the imagination flying off.”

- Jeff Shantz

Herbert Read’s concept of anarcho-poiesis or “anarchist poetics” (Farr 18) sources power from Mikhail Bakunin’s belief that “destruction” of current oppressive systems is necessary to imagine and create [poesis] new economic, social, political and cultural systems. Read’s anarchy pushed to establish a stronger connection between the “person and the doctrine” via art, to ultimately overcome the distinction between art and life (Farr 22). Not surprisingly, however, corporate media has capitalized upon anarchy’s association with destruction to portray it as a wholly destructive force (Shantz 1)

Anarchist creative resistance seeks to alter and destroy the literal it in Kick it Over’s title—societal systems such as capitalism and consumerism, ecological destruction and power hierarchies that anarchists believe are oppressive to an individual’s freedom. Anarchism relies upon the principle of destruction—of unthinking—in order to rebuild and construct new systems. But simply meditating upon revolt “does not make an anarchist” (Antiliff 13). Political and social action of the anarchist individual is needed as well. Creative resistance is that action. Says anarchist theorist Allan Antiliff: “the anarchist may accept destruction, but only as part of the same eternal process that brings death and renewed life to the world” (15). Anarchy’s destructive nature allows for its creative potential in human action (Heckert 8). New institutions, new ways of knowing, can only be endeavored in the face of annihilation of entrenched systems. Alternative visions of social systems and organization are in themselves a means of creative production mirroring a piece of resistance like Kick it Over. Thinking, in the words of anarchist Hugo Ball “can also be an art” (Farr 22).

For anarchists, creative resistance is the key to directing the anger’s energy into productive action. Forms of “token resistance” (Shantz 1), such as voting or sporadically attending political rallies, cannot overcome the entrenched power systems because, in the opinion of Shantz, they do not constitute directed, purposeful and carefully executed action (1). True to corporate media’s representation of anarchism in popular culture, only the “destructive” aspect of anarchy’s creative existence is showcased, while the nuanced creative movements like Kick it Over remain obscure.

According to Shantz, pieces of art like Kick it Over do not exist in an isolated sphere of “art” but in the affecting, “real” world—held directly in the hands of those carrying out the anarchist agenda.

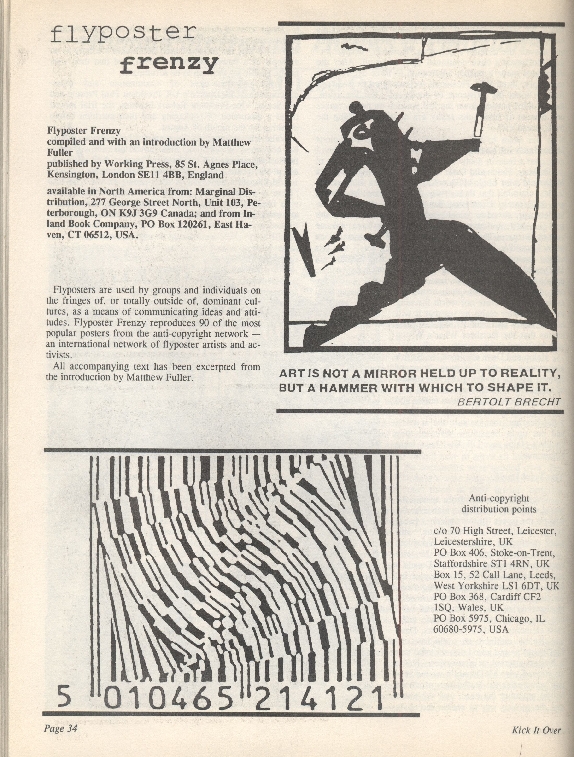

A feature article promoting the use of flyposters.

The title of an autobiographical account (memoir) in Kick it Over.

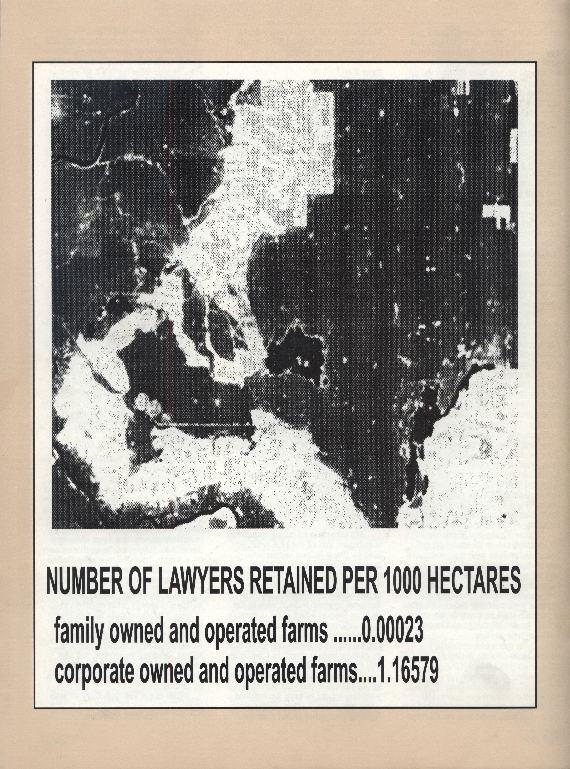

An anti-capitalist cartoon in Kick it Over.

A detailed drawing a bread loaf accompanying a poem on food production.

HISTORY OF ANARCHIST CREATIVE RESISTANCE

Anarchism as a political force has contributed to broad historical, cultural and literary art movements (Shantz 4), influencing publications like Kick it Over. Social movements like communism and socialism, argues Shantz, have been the impetus for new forms of literary production invented to express radical values (4). Antiliff explains that anarchists “create art in tandem with the transformation of society anarchically…interrogating it with this aspiration in mind” (14). In turn, art production within a culture is diversified.

Contemporary anarchist creative resistance first developed internationally during communist mobilization of the 1930s, with the production of socialist folk and jazz music, realist art, and proletarian fiction (3). These movements paved the way for new artistic experiments in North America produced during the 1960s and 1970s. It was during this period that underground, leftist presses (often feminist in nature) began to thrive. Cultures of resistance supported the ideological needs of the counter-movements that produced them (Shantz 4). Common themes found in anarchist creative resistance in both past and present art include: critiques of corporatization, the prison industrial complex, patriarchal norms and ecological destruction. Most importantly, common themes in anarchist creative resistance provide an interior glimpse into the desires and dreams of citizens imagining alternative ways of living (Shantz viii). Aligning with the anarchist commitment to expanding individual thought, and freeing oneself from oppressive institutions, anarchist creative resistance has been historically marked by experimentation with style and form (Shantz 10). In a magazine that holds political cartoons alongside flyposters, memoir alongside elaborate sketches, this tradition of experimentation is clear in the pages of Kick it Over.

A hand-drawn graphic accompanying an article on queer anarchism. This particualr graphic takes inspiration from DIY culture and zine philosophy.

ANARCHIST LITERARY AESTHETICS

“Artistic forms, as words, sounds, images, or movements, symbolize our individual experiences of being human; they materialize our subjective versions of reality, and they contribute to new social forms by communicating our inner worlds to other members of society.”

- Herbert Read (From Nutting's "Art and Organicism" 82)

Anarchist aestheticism, coined by anarchist writer Herbert Read, argues that art which grows out of individual subjective experiences and is free from the constraints of conformity can constitute a revolution in expression (Nutting 82). This aestheticism is seen in the efforts of Kick it Over’s visual and literary art pieces. Anarchist aestheticism, stressing the creative capacities of all members in society, focuses on Do it Yourself (DIY) culture (Shantz 2). Expressive aesthetic practices draw upon punk styles, which emphasize personal freedom of the art producer (Shantz 2). DIY culture and punk influences give some aspects of Kick it Over its more “roughly hewn” and grassroots tone and layout. Anarchist art “names reality and describes reality” (Nutting 82), seen in Kick it Over’s political cartoons—art is key to human survival and is indistinguishable from everyday human existence. Read’s philosophy of anarchist art espoused this accessibility of art—for Read, art was meant to connect individuals to knowledge that would not normally have been accessible (Nutting 82). Anarchist aestheticism contends that as much as art may connect the artist or viewer/reader with the collective, communal anarchist instinct, so too will art provide insight into the self—and it is individual self-awareness and consciousness that anarchists believe will spark social revolution. Art is effective at transmitting political philosophy, anarchists claim, because art communicates aspects of human nature inherently tied to anarchy: imaginative capabilities, consciousness, and perceptiveness (Nutting 85). Anarchist aestheticism contends a confident philosophy of itself: “anarchist literature,” says Vittorio Frigerio, “expects to have an impact on the world” (1).

THE ANARCHIST IMAGINATION

An analysis of the anarcho-poetics giving rise to Kick it Over must entail consideration of the anarchist imagination. Anarchy, and the ensuing social change it champions, could not be envisioned—or enacted—without the radical anarchist imagination. Shantz calls once again to anarchist writer Herbert Read to explain the privileging of the creative, anarchist imagination in the production of literary work. The imagination is considered the pinnacle of anarchist power, representing an ultimate freedom to dream and desire. The creative imagination, argues Shantz, allows the anarchist to experience new realms of consciousness (88). Production of art expands human consciousness, developing an individual’s awareness of the human condition (Shantz 89), and producing fertile imaginative grounds to envision and re-imagine social and economic institutions. The artistic forms in Kick it Over, whether literary or visual, aim to influence the reader’s imagination. The question for anarchist art is “not how to achieve, maintain, and administer power…but rather to awaken and inspire initiative” (Shantz 8). Inspiring the reader of anarchist creative resistance to action cannot occur on the basis of coercion— hence, an anarchist would argue that a piece of artwork like Kick it Over serves the very real purpose of stirring voluntary action within the reader. The autonomy of the reader must not be manipulated, and experiencing Kick it Over as art protects this autonomy.

THE ANARCHIST AS ARTIST

As much as anarchy is opposed to political regulation, limits, and boundaries, it is also opposed to cultural censorship and control. The anarchist artist is not considered to exist in a separate, privileged existence—anarchists believe that anyone who makes art is an artist (Shantz 3). Therefore, all contributors, graphic designers, sketch artists and cartoonists in this issue would be considered artists. Art has a social role in the anarchist culture of resistance, hence anarchist artists remain very much connected to the society they are attempting to transform (Nutting 90). The anarchist artist is also the anarchist educator. By emphasizing that the artist does not operate as a “professional artist” (Shantz 1), and ensuring that no division exists between the artist and non-artist members of society, art is considered to be easily accessible to all. The identity of the “professional artist” is further discouraged because this identity implies a type of expertise in production—that is, the professional artist must produce to validate their existence. Art created by the expert producer implies that the art becomes commodified—the antithesis of what anarchist art is premised to be.

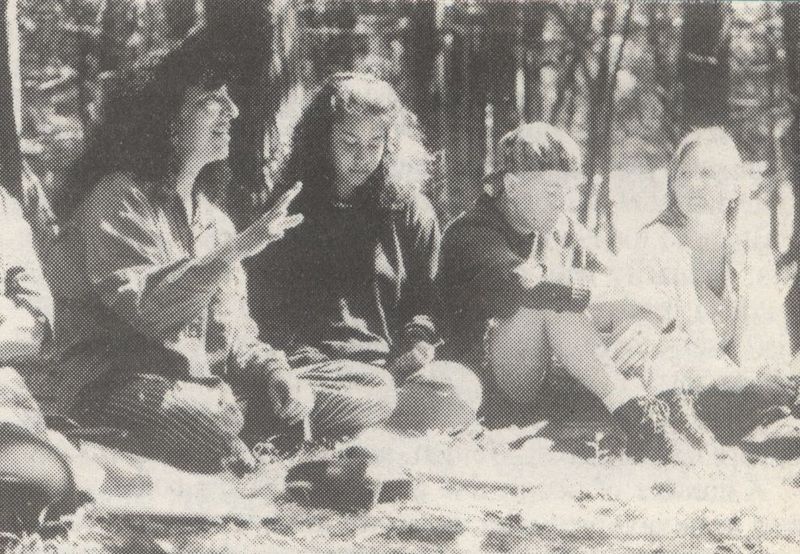

A photograph of anarchists gathered at a summer camp. Though the date and location are unknown, the photograph is an example of the community Kick it Over was supporting in its creative resistance.

The title of an article describing an writer's experience of anarchist summer camp. Similar to the photograph above, the article is catering to a specific anarchist readership.

ANARCHIST LITERARY CULTURE AND COMMUNITY

The cultural and artistic expression of anarchy in the pages of publications like Kick it Over creates anarchist lifestyle solidarity (Shantz 6). Despite multiple names of contributors and artists purposefully excluded from the magazine under the guise of anonymity, a reader of Kick it Over understands that the magazine is a collaborative effort. Collectively produced works of art demonstrate a breaking free from “corporate re/production of culture and art, in both consumption and exchange” (Shantz 7). For the anarchist, cultural productions are designated for personal and community use, rather than for monetary gain. Consequently, works of art like Kick it Over are considered to be gifts, rather than capitalist objects (Shantz 7). Both DIY culture and punk culture align with anarchist artistic expressions encouraging this separation between capital and art. In capitalist, patriarchal society, individuals have little say over the creation of cultural products—commodities—that are consumed. The DIY, punk anarchist retains a high level of control over their garment or object, just as collective members producing the independently run Kick it Over would have had in terms of the magazine’s layout, design, and subject matter. While the average reader of a standard magazine is subject to the consumption and influence of advertisements, Kick it Over’s mocking “advertisements” satirize the coercive nature of actual advertisements. The reader of Kick it Over consumes an “advertisement” and flips over the page enlightened, rather than manipulated. Exposure to an anarchist publication like Kick it Over carries far-reaching cultural implications—more so than a reader’s simple exposure to satirical cartoons or artwork. Kick it Over prompts an alteration of the self that is shackled in authoritarian culture (Gifford 325). The subject matter explored in Kick it Over carries the potential to not only support anarchist literary culture, but to broaden mainstream, corporate conceptions of what constitutes consumer material, and more importantly, what constitutes the magazine as a text.

Cultural experimentation and exchange are key features of anarchist gatherings such as the Active Resistance conferences and numerous anarchist book fairs in Montreal (Shantz 7) where East-coast born Kick it Over would have been shared. Contemporary anarchist creative resistance is built to engage with the needs of the real, working-class community of anarchists, seen here in this article showcasing Anarchist Summer Camp, or in the Discussion Forum section of the magazine. Anarchist community would have been nurtured by its own creative resistance—by the art itself that is, in a sense, collectively produced under a singular political philosophy. Social organization of community for anarchists takes the form of communication, rather than regulation and control. Mutual aid, cooperation, and shared experience all are supported by literary and visual pieces of art like Kick it Over. Nuttig echoes Read when she notes that “words and symbols constitute the very fabric, the synthetic structure, of society” (90).

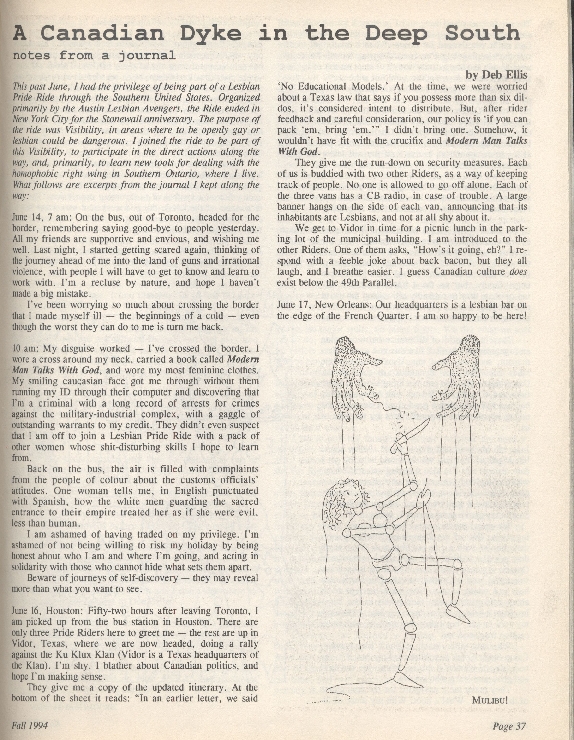

An autobiographical account of a queer anarchist experience, entitled "A Canadian Dyke in the Deep South".

QUEERING ANARCHIST CREATIVE RESISTANCE

“Here’s a queer proposal: the state is always a state of mind…it is self-consciousness, self-policing, self-promotion, self-obsession.”

- Martha Ackelsberg (73)

What does queering anarchism entail? Anarchist scholar Martha Ackelsberg asks “isn’t anarchism enough of a bogeyman that any effort to ‘queer’ it would only make it more alien and irrelevant to mainstream culture?” (1). Queer anarchism parallels contemporary anarchist theory in that it draws links between strict political and economic hierarchies and fixed constructions of an individual’s gender and sexuality (Heckert, Shannon &Willis 1). Queered anarchism critiques identity and subjectivity construction, and examines how certain freedoms and privileges are stripped from an individual when forced to mold their identity according to heteronormative categorization. Queer anarchist cultural production is evident in Kick it Over’s autobiographical, long form feature “A Canadian Dyke in the Deep South”, which explores a Canadian activist’s journey into the United States to attend a series of queer rallies. The feature’s exploration of borders and land is well suited to the Food and Land issue of Kick it Over, but examining the subtleties of the article reveals a metaphor for anarchist queerness. Queer autobiography, states lesbian poet Daphne Marlatt, is the preoccupation of “a border crosser. Or a gender/genre crosser” (viii). Autobiography in particular offers the reader an opportunity to “queer”—to make strange—their conception of what defines (or undefines) anarchist creative resistance. To queer anarchism is to make the strange even stranger. Queering anarchism suggests that anarchy is malleable. Anarchy’s malleability evokes the agency and power of the anarchist’s ability to flex their autonomy within and over this political philosophy. Queer anarchism requires a self-reflexive activist in motion, one who is always performing critique.

Queerness, and its implicit crossing, unraveling, or deconstruction of identity, suggests “the creation of a new itself” (Heckert, Shannon & Willis 3) that creates alternative identities—just as anarchism promotes a destruction of oppressive political and social institutions in favour of alternative options for societal organization.

TENSIONS BETWEEN ANARCHIST PHILOSOPHY AND LITERARY CULTURAL PRODUCTION

Tension exists between Kick it Over’s technical, physical production and communicative format and the philosophical principles of anarchism. Language, argues anarchist poet Hugo Ball, has become a commodity in itself (Nutting, 19). As such, literary forms of communication produced for mass consumption “now mimic, or rather animate, the processes of capitalist production” (Nutting 25). Kick it Over’s denial and resistance to capitalism can be construed as a form of engagement with the very systems it seeks to defines itself in opposition to. Kick it Over, costing $3.00 Canadian, has been given a monetary value by its own anarchist collective. In the first few pages, the collective makes a call out to its readership, imploring for monetary donations to keep the magazine afloat. The collective must participate in capitalism in order to survive, whether or not it actively publicizes this fact. In defense, anarchists argue that organized communication forms constitute social organization (Shantz 24).

Another point of contention embedded in the production of Kick it Over is the magazine’s reliance on technology for survival. Anarchists have historically been wary of technological proliferation, when anarchist writers in the mid-nineteenth century noticed the displacement of workers by machines—and the consequent unemployment and mass production that resulted (Gordon 490). But in keeping with the anarchist commitment to support collective communication, contemporary anarchists promote the development of communication technologies such as the internet, mobile phone, and printing press. Technologies that strengthen environmental sustainability, organic farming techniques, eco-architecture, and permaculture design promote anarchist ethos (Gordon 490). Still, critics of anarchist creative resistance could argue that a publication like Kick it Over, with its sales tag and financial contract established between buyer and object, stands as antithetical to the basic principles of anarchism. How can the pages of Kick it Over demonstrate DIY culture in literary and artistic expression, but adhere to capitalist systems? Is Kick it Over really still considered a “gift” (Shantz 8) as opposed to a commodity? The developed physical qualities of Kick it Over tell a very different story from the magazine’s grittier cousin, the zine. Kick it Over’s experimentation in form and subject matter, replicated time and time again in each issue, could be perceived as institutionalized. Countering these critiques is the anarchist defence that anarchy creates “autonomous zones” (Shantz 9) within the capitalist, patriarchal system that sustain anarchist communities. Kick it Over, then, would have been argued to exist within this anarchist autonomous zone, excusing its participation in capitalism.

PRESENT DAY ANARCHIST CREATIVE RESISTANCE, THE FUTURE OF ANARCHIST CREATIVE RESISTANCE, AND THE EXCLUSION OF ANARCHIST CREATIVE RESISTANCE FROM THE LITERARY CANON AND ACADEMY

Kick it Over’s most recent publication available in the University of Victoria’s Special Collections was published in 2004. No information is available online to provide clues regarding Kick it Over’s demise. It is possible that the Kick it Over opted to forgo print issues in favour of a digital platform. One website, http://kickitover.org/, heralds itself as an anarchist economic project supported by Adbusters. The site encourages university students to download activist buttons and stickers, and has resources for budding anarchists, such as the Revolution Planning 101 downloadable booklet. No definitive correlations can be drawn between the print publication of Kick it Over and the website, and the most recently updated post on the website was published in 2015.

If it is not possible to fully deduce the fate of Kick it Over, the curator is pressed to ask: what is the future of anarchist creative resistance?

To start, the many anonymous articles and graphics published in Kick it Over during its long publication run—and which painstakingly document anarchist historical events—now go without recognition. A lack of engaged analysis of contemporary anarchist politics in academia means that anarchist creative resistance, and alternative forms of cultural production, remain overlooked. Jeff Shantz, the frequently quoted anarchist scholar in this exhibit, notes that a “substantial gap in understanding overlook[s] connections between anarchist perspectives and cultural expression” (13), and that this gap continues to grow in academia. Shantz would know—he is one of few prolific, contemporary anarchist scholars whose research on anarchist cultural production is widely available online.

When anarchist art is examined in academia, it is understood to be simply one component of a larger leftist project (Antiliff 11), meaning that the nuanced complexities of anarchist art are not thoroughly attended to via serious scholarly inquiry. Most noticeably, it is the absence of Kick it Over from digital archives that reveals its perceived insignificance to current humanities researchers.

Without the attentive and critiquing eye of the academy, anarchist creative resistance will continue to risk being perceived as an immature, underdeveloped or unrefined art form. Worse, without sustained analysis, anarchist creative resistance is susceptible to the reproduction of corporatized messages about its identity that swirl within North American cultural memory. Study of anarchist creative resistance is necessary to continue dispelling myths about anarchism that define it as a violent and unsophisticated political philosophy.

The demise of Kick it Over, and its minimized existence within academia, suggests troubling inquiries that merit further research: (1) Why is there such a lack of scholars who study anarchist creative resistance? (2) Is success in academia not synonymous with anarchist existence or self-identification? (3) What other forms of anarchist cultural production are being overlooked or understudied? And (4) What form of literature does Kick it Over become in the face of post-anarchism? (Rousselle 236)

Kick it Over serves to remind humanities scholars to continue investigating the obscure, and to continue making strange what they find there.

Works Cited

Ackelsberg , Martha. “Preface.” Queering Anarchism: Addressing and Undressing Power and Desire, Edited by C.B. Daring et al., AK Press, Edinburgh, 2012, pp. 1–4.

Antiliff , Allan. Anarchy and Art: From the Paris Commune to the Fall of the Berlin Wall. Vancouver Arsenal Pulp Press, 2007.

Farr, Roger. “Poetic License: Hugo Ball, the Anarchist Avant-Garde, and Us.” A Creative Passion: Anarchism and Culture, Edited by Jeff Shantz, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle, 2010, pp. 15–30.

Frigerio, Vittorio. “Against All Authority: Anarchism and the Literary Imagination.” Anarchist Studies, 2012.

Gifford, James. “Place, Personalism, Anarchism, &Amp; Fantasy: Recasting Late Modernism.” Literature Compass, vol. 12, no. 7, 2015, pp. 322–333.

Gordon, Uri. “Anarchism and the Politics of Technology.” Working USA, vol. 12, no. 3, 2009, pp. 489–503.

Heckert, Jamie, and Abbey Volcano . “Anarchy without Opposition.” Queering Anarchism: Addressing and Undressing Power and Desire, Edited by C.B Daring and J Rogue, AK Press. Edinburgh, 2012, pp. 63–75.

Heckert, Jamie et al. “Queer Anarchism .” International Encyclopedia of the Social &Amp; Behavioural Sciences , 2nd ed., 2015, pp. 747–751.

Lynes, Genevieve. “Poetic Resistance and the Classroom without Guarantees.” Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature, vol. 15, no. 3, 2012.

Nutting, Cathering M. “Art and Organicism: Sensuous Awareness and Subjective Imagination in Herbert Read’s Anarchist Aesthetics.” Ungovernable Hearts: Anarchism and Literature, vol. 45, Georgia State University Press, 2014, pp. 81–94.

Rousselle, Duane. “Georges Bataille's Post-Anarchism.” Journal of Political Ideologies, vol. 17, no. 3, 2012, pp. 235–257.

Shantz, Jeff. Against All Authority: Anarchism and the Literary Imagination. Exeter, Imprint Academic, 2011.

Shantz, Jeff. “Introduction .” A Creative Passion: Anarchism and Culture , Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle, 2010, pp. 1–15.

Shantz, Jeff. “Introduction .” Ungovernable Hearts: Anarchism and Literature , vol. 45, Georgia State University Press, 2014, pp. v-viii.

Woodcock, George. Anarchism : A History of Libertarian Ideas and Movement. University of Toronto Press, 2004, ProQuest.

RL/Fall2016