Jean Paul Sartre's Existentialism and Human Emotions (1947, 1957), with marginalia from Robert Sward (1953, 1958)

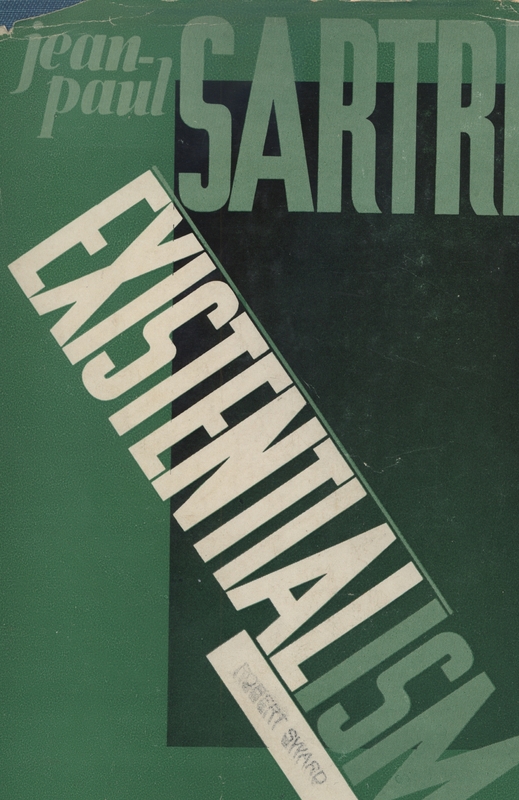

Cover of Jean-Paul Sartre's Existentialism, 1947. Robert Sward's name stamped on the front.

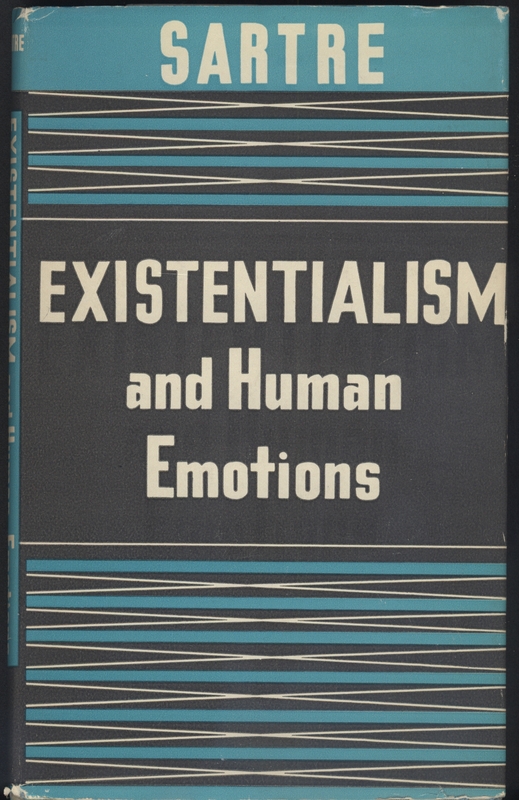

Cover of 1959 edition of Existentialism and Human Emotions.

Introduction

These two books, and their inclusion in the Special Collections Library, make an important twofold statement:

- Authorship, as it pertains to inclusion in Special Collections, is influenced by multiple factors, and cannot necessarily be allotted to a single party.

- Special Collections values the contributions made by multiple authors and influences on the book, and in doing so demonstrates the value of the book as a physical object that can be changed/influenced, the value of the text as it pertains to multiple iterations of any one conceptual object, and the value of textual marginalia.

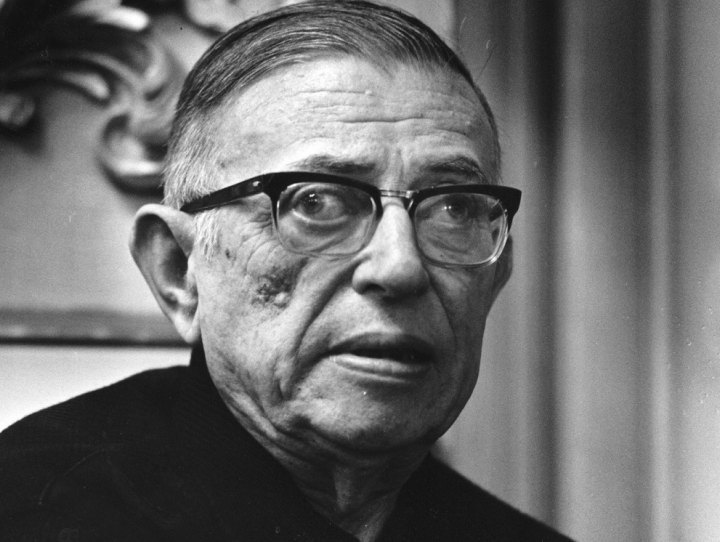

This first image is the cover of a copy of Jean Paul Sartre's Existentialism, published by Philosophical Library in 1947, which bears the name Robert Sward stamped onto the cover.

The second image, the cover of Sartre's Existentialism and Human Emotions, dated 1953, bears a similar geometric design on the dust jacket, with similar colouring, and is the next edition in the same series, by Philosophical Library.

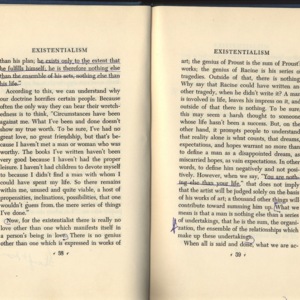

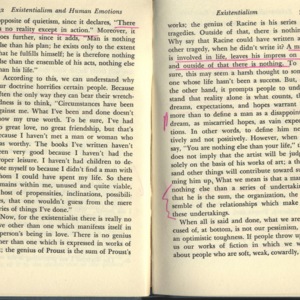

Despite different titles, both of these texts mainly contain the same excerpts from Sartre's paper on "Existentialism as a form of Humanism," with additional excerpts from Sartre's Being and Nothingness.

These texts, however, have a connection beyond the collected works of Sartre: both texts were owned and signed by Robert Sward, poet laureate, novelist, and former University of Victoria teacher and scholar.

Sartre originally delivered this paper as a speech in 1946 under the title L’existentialism est un Humanisme - or Existentialism is a Humanism. Given that the text was originally a speech in French, then translated into English and compiled along with parts of Sartre’s other works and interviews, all in order to capture the North American market, the idea of Authorship, or intended Authorship, is problematic.

The Authorship of these books is also complicated by Robert Sward's name, written on not just the inside of both versions, but the cover of the 1947 edition as well. While Robert Sward's notes in the text are intended to aid his own reading, his influence on the texts and his importance to the University of Victoria, both as a teacher and a writer, has caused these texts to be collected and maintained in the Special Collections section of the McPherson Library.

Authorship

Jean Paul Sartre (1905-1980)

Sartre was a French writer, literary critic, theorist, novelist, political activist, playwright, and biographer. Sartre was of the philosophical school of existentialism, and studied the works of Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger before creating his own theories. His biography as a Nobel Laureate argues that despite working in an existing field, "the existentialism Sartre formulated and popularized is profoundly original" (Nobel Media). Sartre expressed his theories through multiple forms of media, most notably in plays such as Les Mouches (The Flies, 1943), and Huis Clos (No Exit, 1947), as well as notable philosophical works such as L'Etre et le néant (Being and Nothingness, 1943) and L'Existentialisme est un humanisme (Existentialism is a Humanism, 1946), both of which are present in full or in excerpts within the two works in this exhibit. Despite his popularity as a philosopher, it was actually "Sartre's first novel, La Nausée (Nausea), 1938, and the collection of stories Le Mur (The Wall and other Stories), 1938, brought him immediate recognition and success" (Nobel Media). He went on to receive a Nobel Prize in literature in 1964.

Sartre's existentialism was groundbreaking in its time, and "its popularity and that of its author reached a climax in the forties" (Nobel Media). Capitalizing on this popularity, the Philosophical Library publishing company included Sartre's works in a collection of "must-have" books for any home library, many of which, such as the biographies of Albert Einstein and Winston Churchill, place a much greater importance on the name or prestige of the author than the actual content of the works.

Looking at the covers of the two books, Sartre's name is as large as the title, obviously promoting his popular name to increase sales. Both of these books contain excerpts from multiple works by Sartre compiled along with a larger complete work, which points to the importance of the Author over the importance of the field of study, or even over the importance of individual ideas, thoughts, or works.

In this way, the impact of Jean-Paul Sartre's popularity is just as important to these texts as his authorial voice.

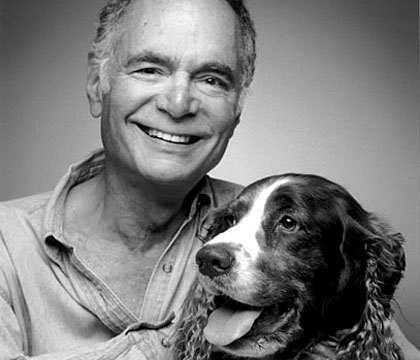

Robert Sward (1933-Present)

Sward began what would become a long and successful career by writing what he refers to in his biography as "Switchblade Poetry" in Chicago at the age of fifteen. This meant using poetry to communicate messages between members of his gang, which started through the innocent act of including rhymed couplets in messages. For example:

The Semcoes meet next Thursday night

at Speedway Koko’s.

Five bucks dues, Foxman, or fight.

- Robert Sward, Biography

Sward joined the Navy and was stationed in Korea in 1952. In 1962, he published Uncle Dog and Other Poems, and began working as a writing teacher at Cornell University in 1964, publishing his second book, Kissing the Dancer and Other Poems in 1964 with the Cornell University Press. Since then, Sward has continued writing and teaching, having taught at the Iowa Writer's Workshop, the University of Victoria, and the University of California, Santa Cruz.

He has also worked in media, conducting 60-minute interviews with Canadian legends like Margret Atwood and Leonard Cohen on the CBC, and writing as a book reviewer and journalist for the Toronto Star and the Globe and Mail in the 1980's.

Some of his other works include Heavenly Sex (2002), The Collected Poems 1957-2004 (2004), and God is in the Cracks (2006).

Sward was clearly influenced by Sartre's work, as he annotated the text twice, with five years in between each annotation. Existential concepts are also present to some extent within Sward's writing. Below is an example of a short poem with clear existential themes, such as the invasive sense of "nothingness." The poem is called "All for a Day," and is taken from his 1964 collection Kissing the Dancer and Other Poems.

All For a Day

All day I have written words.

My subject has been that: Words.

And I am wrong. And the words.

I burn

three pages of them. Words.

And the moon, moonlight, that too

I burn. –A poem remains.

But in the words, in the words,

In the fire that is now words.

I eat the words that remain,

And am eaten. By nothing,

By all that I have not made.

- Robert Sward, Kissing the Dancer and Other Poems

Sward is still actively working and writing, publishing in Canada with the Black Moss Press. He has two forthcoming books, Love Has Made Grief Absurd, and New and Collected Poems, 1957-2017.

Sward on Sward:

Robert Sward on the Marginalia of Robert Sward

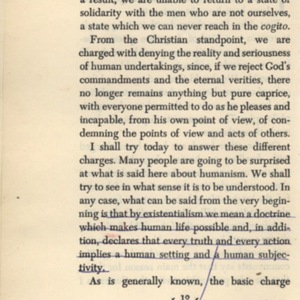

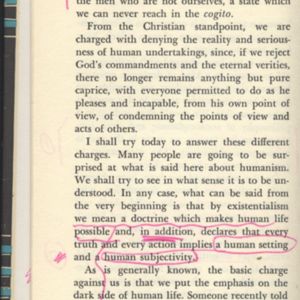

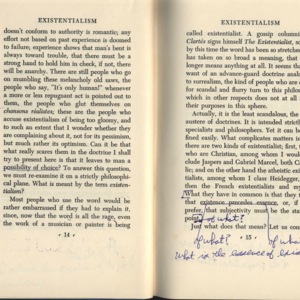

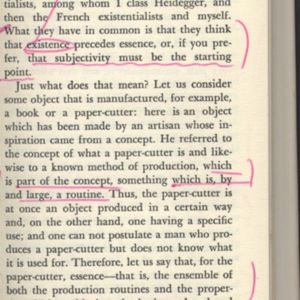

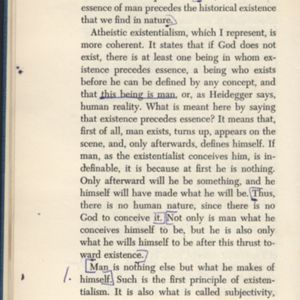

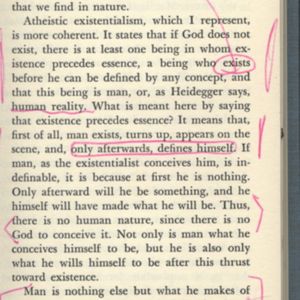

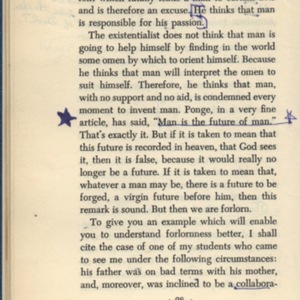

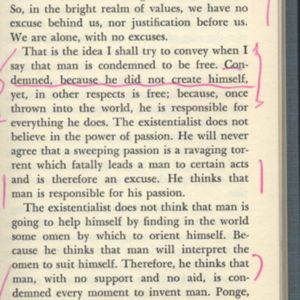

This gallery shows the notes that Robert Sward made in 1953 in the '47 edition of the text as compared to the notes he made in 1958 in the '57 edition of the text.

The notes were scanned by me and sent to Robert Sward in November 2016, and he returned the following comments on his own notes from 60 years earlier.

1. “…the implications for personal action of a universe without purpose.” What is the freedom of which Sartre speaks? How does that “freedom” relate to non-traditional forms like free verse, syllabic verse (à la Marianne Moore or Dylan Thomas…or…) and how does a poetic “voice” speak, and how is it heard by readers in "a universe without purpose?”

For someone like myself, someone deeply influenced by Walt Whitman and Mark Twain and Alan Ginsberg, someone who came of age, so to speak, at the University of Iowa’s Poetry Workshop—I earned a degree and went back to teach at Iowa in the late 1960s— …certainly I was “acutely aware” of my freedom.

2. Still pondering that question, whether or not (my) existence precedes my existentialism. Tonight, the answer to that question is yes, of course.

3. Subjectivity is the starting point. Can existence choose its essence? I’d like to think so!

4. Looking back at these jottings, circa 1953, age 20, just getting out of the Navy, just about to start college, reading Sartre, “…that by existentialism we mean a doctrine which makes human life possible, and in addition, declares that every truth and every action implies a human setting and a human subjectivity.”

I think of William Blake, a human form… and I’m grateful to Sartre. He helps draw the curtain, open the curtain, I guess. I mean, I emerge from the darkness of gray, bleak Chicago, where I was born and raised, and, yes, still admire and love the city… still, happy I joined the Navy as I did, happy for the G.I. Bill, happy to have encountered Sartre… He even influenced my decision to study French in College.

5. And ask, picking up where we left off before, “What of the original action, the creation of the world or universe?"

But if the universe exists without a purpose, if there is no Creator, (no “originality”…), bleak, O bleak!

6. Are any of the standout poets, Canadian and American poets c. 1960s, is any their production not “caprice?” To use Sartre’s word...

Living among the archives:

Robert Sward on Existentialism and Authorship

After discovering these two books in the McPherson Special Collections, and finding the name Robert Sward in the front of each, I started a search for information on the Canadian-American poet/novelist. My search culminated in the best source of information I could hope for on Robert Sward: the man himself. He graciously agreed to look over his old marginalia, and to be interviewed for the exhibition.

Sward kindly agreed to an interview for inclusion in this exhibit. He began answering questions before he received copies of his own marginalia, but has also made specific comments about individual notes in the previous section. The interview was conducted via email between November 24th and December 12th, 2016.

Q:

Your biography says that you were stationed in Korea in 1952, and your signature in the earlier edition says "Robert Sward, August 1953." I'm wondering where your interest in existentialism (and Sartre in particular) started. Is it related at all to your time in the war?

A:

Truth is, I wasn't formally stationed in Korea. At age 19 or 20, I served in the U.S. NAVY on board an LST, Landing Ship Tank 914, and engaged in manoeuvres in and around Korea. Dangerous duty, officially a Combat Zone because waters were mined and some of our manoeuvres, later, were occurring off the coast of China.

Among other duties, I served as the Ship's Librarian and found time to read everything I could find, including Sartre. I'd say yes, my interest in existentialism began at that time, cruising over mines. As flat-bottomed LST, we sailed easily over mined waters, but as you can imagine, there were no guarantees.

For me, having missed out on WW2, I wanted to gain experience, wanted to test myself in combat situations. And Sartre, though at age 19-20 I scarcely knew anything about him, or about existentialism, or what exactly I was with looking for, somehow gravitated toward this... mysterious philosophy, which seemed to offer a way by which one could understand...

Q:

My next question regards your time at University of Victoria as a visiting lecturer and assistant professor. How did your time at the University and on Vancouver Island influence your writing? In 1970, you founded the Soft Press in Victoria, and I was wondering if you could comment on that, or on the influence of the University/your time here on that project?

A:

Full answers to your questions about UVic and Soft Press, etc., are contained in “Contemporary Authors, CA,” Volume 206, published by Thomson Gale. Here is a relevant sample:

“In 1969, Invited by Robin Skelton, I came to Victoria to visit some classes and give a fifty-minute poetry reading. Soon after, I was offered and accepted a teaching position that was supposed to keep me in British Columbia for nine months. I met my classes and wrote poems about prehistoric English crocodiles, tea-drinking Royalists, Tories in their glory. I held classes at our home in Oak Bay. This was said to be unorthodox. There were complaints. My teaching methods were said to be controversial which, I suppose, is true. Nonetheless, to my surprise, I was rehired to teach a second year. My daughter, Hannah, was born in 1970, and I purchased a three-story, tudor-style home in quiet, stodgy Oak Bay for $18,500. In 1971 I was promoted to assistant professor, given a bonus and a new two-year contract and other inducements.

“In 1973 I met and in 1975 married a Russian-born, French-Canadian artist, Irina Schestakowich. What started out as a fifty-minute, Northwest Poetry Circuit appearance led to my living in Canada for fourteen years. Later I became and to this day remain a Canadian citizen…"

Another sample follows:

“ ...Anyway, apart from writing a book—and what led, or may have led, to the writing—there is always the story of the author’s adventures in seeing the volume through the editing, design and production stages and into print. Founder of a Canadian publishing house (Soft Press, Victoria, B.C.) and, later, production manager at a commercial publishing firm, I like to be as involved as possible in all aspects of a book’s creation. My podiatrist father used to say that it takes as many as thirty people to produce a good pair of shoes. Quality book production is also a collaborative process. Still, no matter how involved an author has been, at one stage or another, it is necessary to surrender control and simply pray for the best. Like a mother in labour, one never really knows what your creation is going to look like until you hold it in your hands…"

Q:

This semester, we have been discussing Roland Barthes concept of "the death of the author." In your opinion, how important or unimportant is knowledge of the author or the author's life to understanding and interacting with their works? Do you prefer your readers to know about you as an author?

A:

Yes, I feel that if readers do know something about me that can—generally speaking—enhance the experience, add to the overall understanding of the work. In the late 1950s, a graduate student at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, we were reading the then-standard text “Understanding Poetry,” yes, fifty odd years ago, but I remember the so-called New Criticism, which encouraged the reader to stay away from an author’s biography. The “science” of criticism (critics like Brooks and Warren, R.P. Blackmur, et al) were all the rage at the time.

The “work” was the thing, we were told. If you were a serious scholar or would-be critic, you were asked to forget whether an author was or was not a liar, cheat or just a run of the mill nincompoop. Liar, cheat or nincompoop, she or he might still have written a masterpiece. Students at the time were instructed to read and dissect the work with zero concern about whether or not the author was a “bad” or “good” human being. All the student’s attention was to be directed to “the work itself.”

Yet, anyone who attends a live poetry reading and brings to the event a certain body of knowledge about the author and his or her background and some sense of the context out of which he or she writes… Ask yourself, does that “advance" knowledge of the reader and his or her biography, does that in any way enrich the listener’s experience?

One final point: in the 1950s there were the academic poets, formalists often, “gray-faced academics” they were called (by the Beats) and poetry then was to a large extent ignored by the public, readings sparsely attended… a lonely art one shared with a few close friends. That was then. In the late 1950s in the U.S. at least, Ginsburg, Kerouac… Charles Bukowski… Al Purdy in Canada… a breath of fresh air!

Q:

My final question: to what extent does authorship of a book change? These books have been saved in the Special Collections Portions of the McPherson Library because of your annotations and links to the university, not the original content from Sartre. One of them bears your name on the cover alongside his (albeit smaller and stamped). How do you, as an author, feel about the idea of authorial fluidity within the text? Do you think of these annotated texts as your own works, in any sense?

A:

The short answer is "Good heavens no!"

The annotated texts are just me responding to an idea with this way I have of engaging, now and then, with the text. I'm thinking out loud, an exchange, if I can call it that, with a mind, Sartre, that provokes a response. A private exchange. That's it! Surely you're not imagining me as someone looney enough to think... to hallucinate, to think of these idea twitches as a form of authorship?

If I put my name on a book, cover or anywhere else, it's just a way of increasing the odds that the book will be returned. In a sense it's a sign I value the work, that I want to share it, but that I also want it back. *Not* because I somehow contributed something under the heading of authorship, but just want the damn thing back.

Conclusion

While the concept of Authorship is debatable and problematic, especially in texts such as these, the power of the author is still present. The importance and popularity of Jean-Paul Sartre as an author led his works across the ocean, and into the hands of Robert Sward.

Being somewhat of an existentialist myself, I had, before interviewing Mr. Sward, accumulated a great many ideas about the profound meaning of his name on the cover of Sartre's work. Hoping to gleam some insight, I asked him if he felt any claim to the text, or authorship over it, since his influence had let to its being saved in Special collections. As in the above interview, Sward's response put into perspective just how speculative my previous theories had been.

The authorship of a text such is always somewhat problematized by the massive influences that went into the text, as with the influences on these texts by translations, publisher preferences, compilations of works, and the influence of Sartre himself and his popularity. However, despite the many complications to expressing authorship in a text such as this, it is clear that the importance of a text can come from both the author itself and the influence that it has on others. Just as Sartre studied Heidegger and Husserl before him, Robert Sward studied Sartre. In his own words, these notes were not made in an attempt at authorship, but rather to find "a way by which one could understand" (Sward, 2016).

Works Cited:

"Jean-Paul Sartre - Biographical". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB 2014. Web. 9 Dec 2016. <http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/1964/sartre-bio.html>

Sartre, Jean Paul. Being and Nothingness. New York: Routledge. 2003. Print.

Sartre, Jean Paul. Existentialism. Trans. Bernard Frechtman. New York: Philosophical Library. 1947. Print.

Sartre, Jean Paul. Existentialism and Human Emotions. Trans. Bernard Frechtman, Hazel E. Barnes. New York: Philosophical Library. 1957. Print.

Sartre, Jean Paul. Existentialism is a Humanism. Trans. Phillip Mairet. Web. http://homepages.wmich.edu/~baldner/existentialism.pdf

Sartre, Jean Paul. Existentialism and Human Emotions. Trans. Bernard Frechtman, Hazel E. Barnes. New York: Philosophical Library. 1957. Print.

Sartre, Jean Paul. Existentialism is a Humanism. Trans. Phillip Mairet. Web. http://homepages.wmich.edu/~baldner/existentialism.pdf

Sward, Robert. Biography. Robertsward.com/about

Sward, Robert. Email Interview. 24/11/16-12/12/16.

Sward, Robert. "All for a Day." Kissing the Dancer and Other Poems. Cornell UP, 1964.

Sward, Robert. Notes on Marginalia. Nov 28th, 2016.

MR / Fall 2016