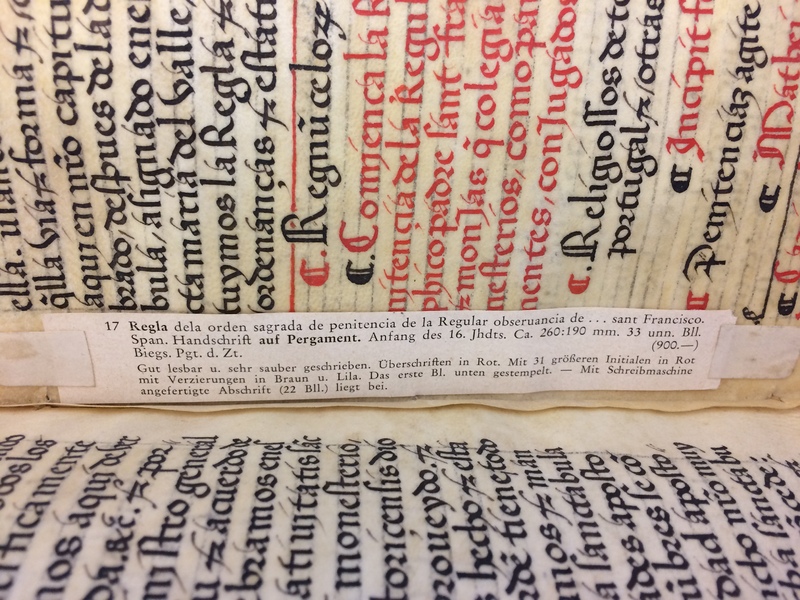

Ms. Span. 1: Antonio de Tablada, Regla de la Sagrada Orden de Penitencia (c. 1528-1530)

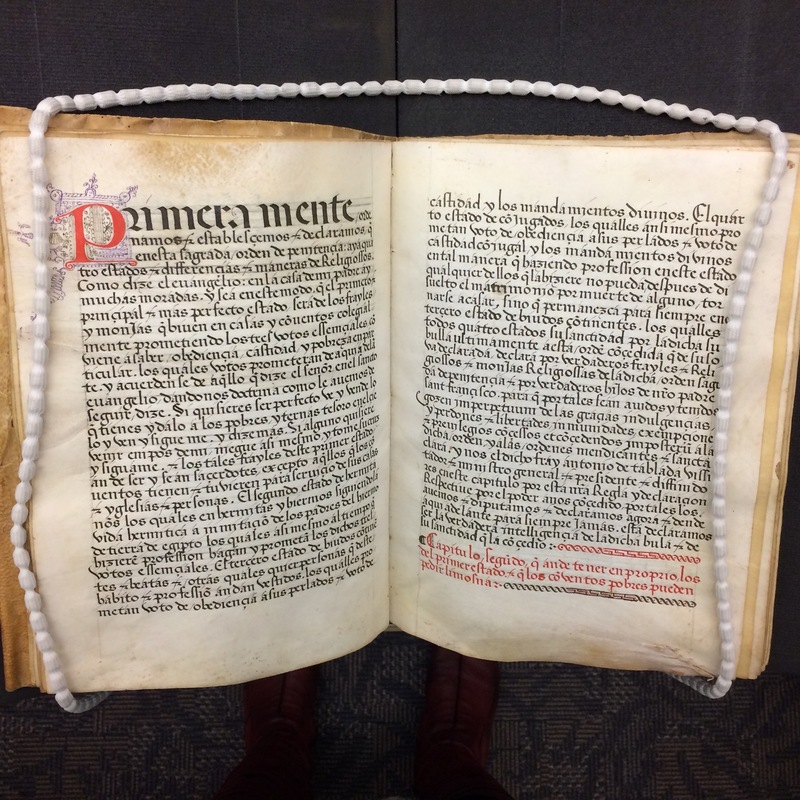

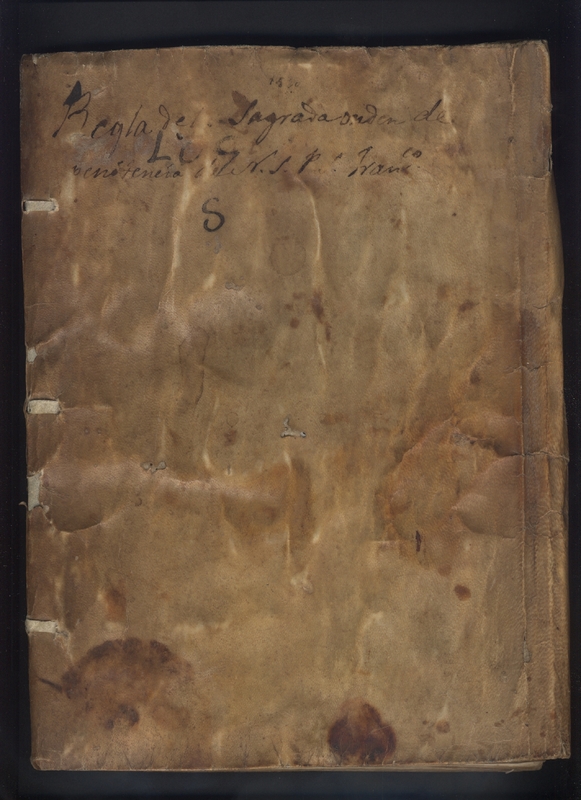

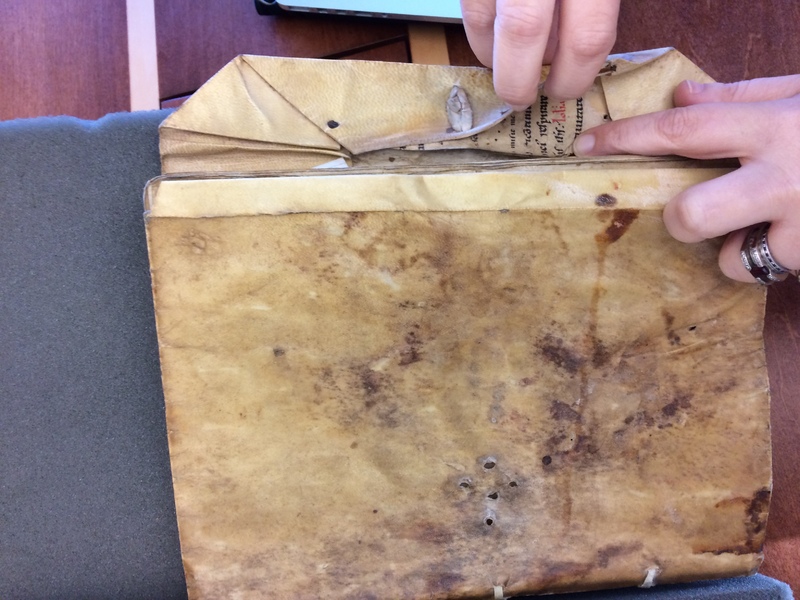

Figure 1.1: Codex cover, Regla de la Sagrada Orden de Penitencia, c. 1528-1530, Spain.

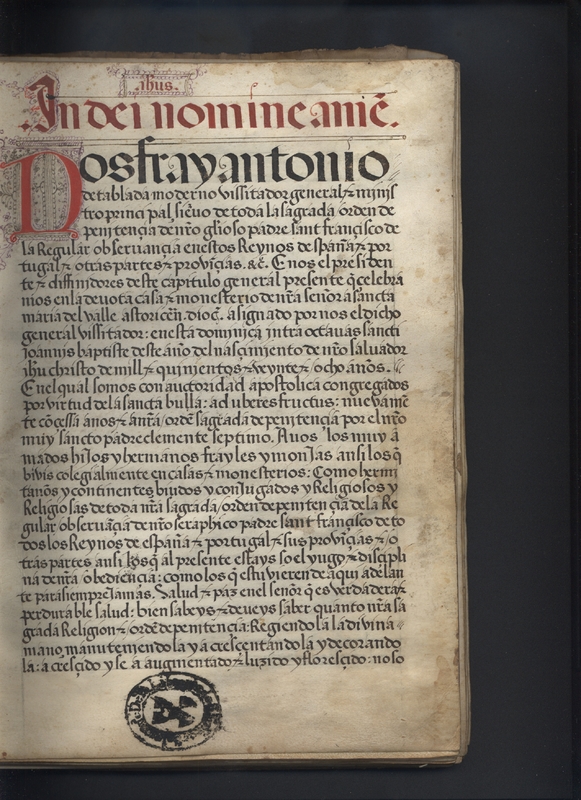

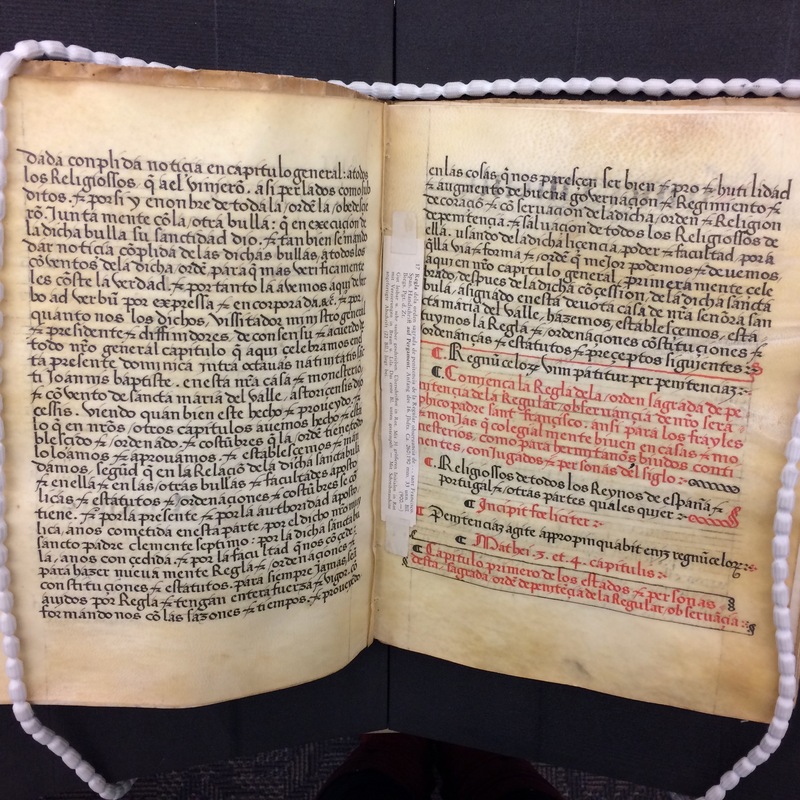

Figure 1.2: Folio 1r. first folio of manuscript.

Figure 1.3: German bookseller slip.

Introduction: The Book As an Object

A note on terminology: All manuscript terminology will appear for the first time in bold, for which definitions can be found at the bottom of the introduction. Further terminology not appearing in the introduction but used later is also included.

Origins and Provenance

With the apparent absence of extant copies, and an almost complete lack of scholarship on the manuscript, the origins of University of Victoria’s MS. Span.1 are somewhat shrouded in mystery. According to the vendor description by Les Eluminures, the manuscript was disseminated by Fray Antonio de Tablada, Visitor General and Chief Minister of this Third Order Regular in Castile and León (as well as Andalusia), for the Brothers and Sisters of Penance of the Third Order Regular, c. 1528-1530. Regla de la Sagrada Orden de Penitencia de la Regular Observancia dela Nuestra Seraphica Padre Sant Francisco (or: “Rule of the Holy Order of Penance of the Regular Observance of our Seraphic Father Saint Francis”), as the manuscript has been dubbed (by a scribe writing in a time period significantly later than the scribe who copied the work itself) is a sixteenth-century Spanish manuscript from the province of Zamora, in Castilla-León, Spain (Les Eluminures). Les Eluminures also claims the manuscript has some connection to the Convento de Santa Maria del Valle. Regla makes mention of Pope Clement VII and includes his papal bull, which implies the manuscript was created sometime after his 1528 Rule (Les Eluminures), in response to the Rule, which was the official endorsement by the pope of the Third Order Regular practising in this part of Spain.

A note on the history of Franciscans and the Third Order Regular

Although we know little about the people who used Regla de la Sagrada Orden de Penitencia, we do know quite a bit about Franciscan orders, and the Third Order Regular, which helps us better understand the context of the manuscript. The Third Order of St. Francis springs from twelfth century penitential movements. These early brothers and sisters of penance would embody the lifestyle of sinners, and would, of their own free will, adopt chastity and fasting, would wear simple attire, and would engage in prayer and acts of public charity (Les Eluminures). Although most scholars believe St. Francis did not, in fact, initiate the order, it was inspired by his teachings and his simple religious life. The Third Order was an order for laypeople, being neither mendicant nor monastic, and thus could include those who wished to continue their way of life with their families, albeit in a simpler, more penitential way. Although the order allowed secular people to engage in a religious life while living in their own homes, it required a life commitment, and once entering into it, members were not allowed to give up their vows and go back to their old ways of life (Supra Montem). There were four types of penitents belonging to the Third Order: religious recluses, those living near a monastery so as to be able to participate sufficiently, those living with their families, but taking vows of penitence, notably (but not always) sexual abstinence, and those living in fraternities and participating in acts of charity, such as caring for the sick (Sastre Palmer). These penitential styles, or “states,” of the Third Order Regular, are outlined in the first chapter of Regla, which I have transcribed and translated here.

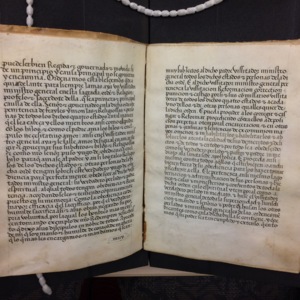

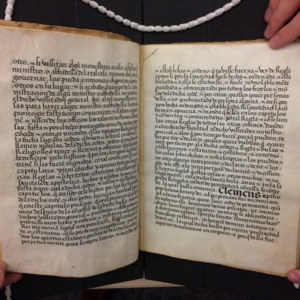

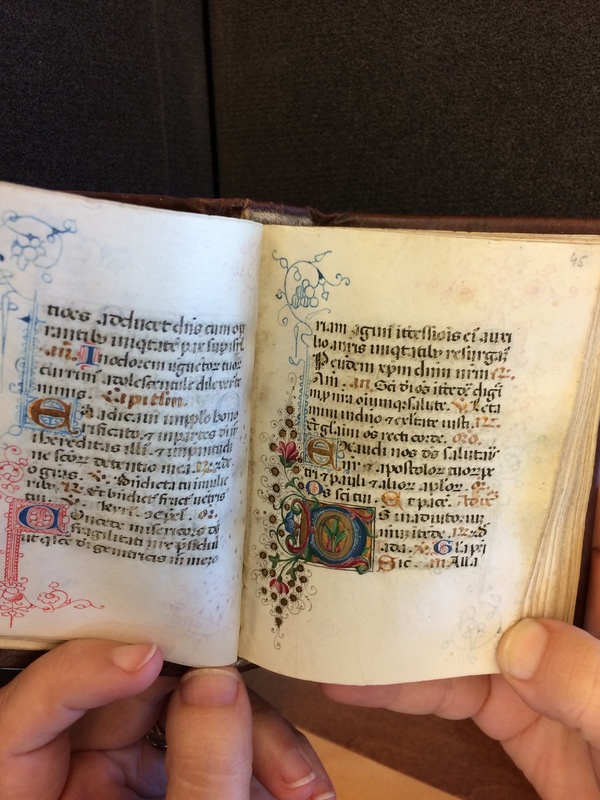

Manuscript appearance

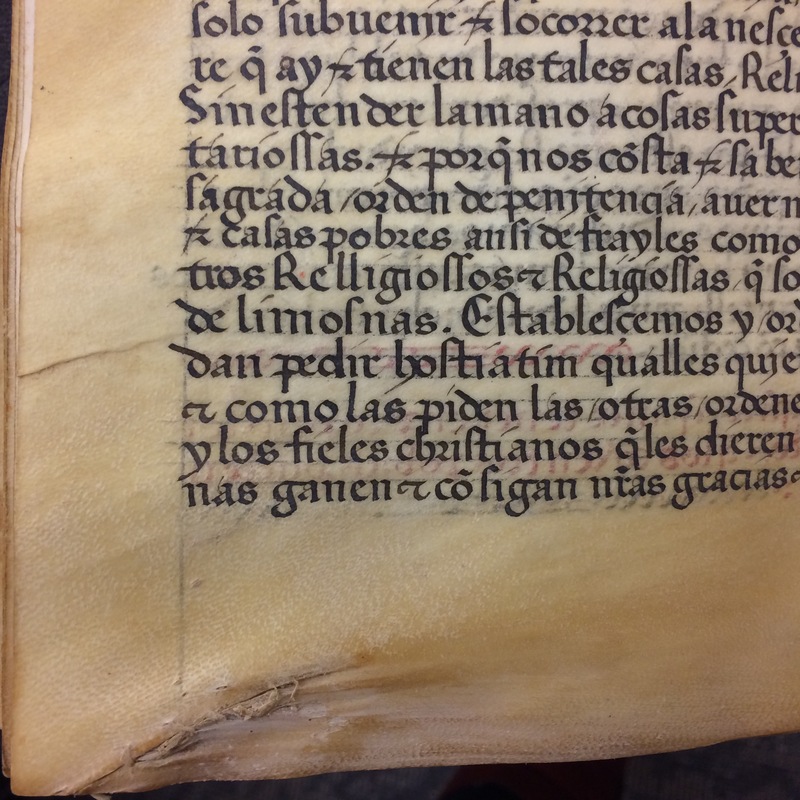

Appropriate to its name (“Rule of the Holy Order of Penitence”), the appearance of the manuscript is somewhat ascetic, and although it was clearly put together with care (the bookhand is a very legible Iberian Gothic Rotunda, and chapters are well organized and easy to follow, each beginning with enlarged, decorated initials), the book is in no way ostentatious. The codex cover, like the rest of the manuscript, is in parchment (animal skin), and shows evidence of its previous life in its wear – the parchment is wrinkled, and looks like old skin. The book still has its original wallet binding (Les Eluminures), a late medieval limp binding that, due to its lack of wooden binding board, was lighter and easier to carry around. Two leaves appear to be lacking (of an original thirty-three leaves), but otherwise the text is intact. The exterior of the manuscript is wrinkled and worn-looking, and seems to be missing a clasp, leaving four small holes in the parchment of the reverse binding where the clasp once would have attached. Two tiny worm holes poke through the front outer binding, accompanied by their trails. Despite its age and some wear, however, the text remains very legible.

While the manuscript does have a somewhat humble appearance, it is organised with care, according to typical practices during this period (wallet binding, rubrication, decorated initials). Chapters begin with decorated, rubricated initials, headings to introduce new sections are also rubricated, and the text is in a very legible Iberian Gothic Rotunda bookhand in black ink. Elegant yet unpretentious line-fillers with alternating red and black ink appear at the beginning and end of some sections near the beginning of the manuscript, decorative lines in black and red ink used to mark the beginnings and ends of sections, often surrounding rubricated text which serves to introduce the chapter which follows. Paraph markings are used to draw attention to certain passages. Catch words appear in the lower margins of the verso folios to act as binding aids to ensure the right folia are bound together.

A note on my transcription of the text

I have provided a transcription and translation of the first chapter of the text, and have elected to do a fairly diplomatic transcription, visibly expanding contracted words (using italics for letters which have been omitted). I have maintained Early Modern Spanish spellings. One noticeable difference between Early Modern spellings and modern equivalents is the interchangeability of u’s and v’s––meaning that the modern Spanish “evangelio” may appear as “euangelio.” Another noticeable, though less surprising difference, is the interchangeable use of v and b (common in Modern Spanish mis-spellings of words, due to the similar sound of the two letters). It is also important to note that the double l in Spanish (“ll”) found in words like “llamar” (to call), which in Modern Spanish makes a “y” sound, in Early Modern Spanish seems to be indistinguishable from the singular “l,” and so words often having only one “l” in Modern Spanish may have two in Early Modern Spanish. While I have maintained the original spellings in my transcription, I have, however, chosen to include punctuation (which does not exist in the manuscript, except very rarely, and not in its modern forms), for greater facility of reading.

Where does the Early Modern manuscript fit into the history of the book and print culture?

Perusing a modest, yet carefully organised and even beautiful Early Modern manuscript such as Regla de la Sagrada Orden de Penitencia offers an important glimpse into the history of pre-print culture. The time-consuming effort it would take to copy out a manuscript such as this by hand, in such an elegant and neat bookhand (not to mention the extra work done by rubricators to demarcate new chapters and important sections), bespeaks the importance of recording the information. While this particular manuscript hails from Spain, its contents tell us something about a religious order that extended throughout Europe, and today has spread considerably, stretching across world as far as Asia and South America (Bede). It is therefore a valuable part of both global cultural history, and the history of the written word.

Medieval Manuscript Terminology

Manuscript: A book which is written by hand, (manu: “hand,” derived from the Latin “manus,” and script: “writing, derived from the Latin “scribere”).

Codex: A book format, especially used referring to ancient manuscripts.

Folio: A leaf of parchment, or of paper.

Recto: The front side of a folio.

Verso: The back side of a folio.

Bifolium: A folded piece of paper or parchment, creating two leaves.

Quire: A group of bifolia bound together (usually four or five, yielding 8-10 leaves).

Initials: Enlarged capital letters.

Rubrication: The use of red to make certain text or symbols stand out.

Paraph: A symbol used to indicate a new section of text (sometimes, but not always, used to indicate what would today be a paragraph).

Bookhand: A formal script.

Scribe: The copier of the manuscript, not necessarily the author of the text.

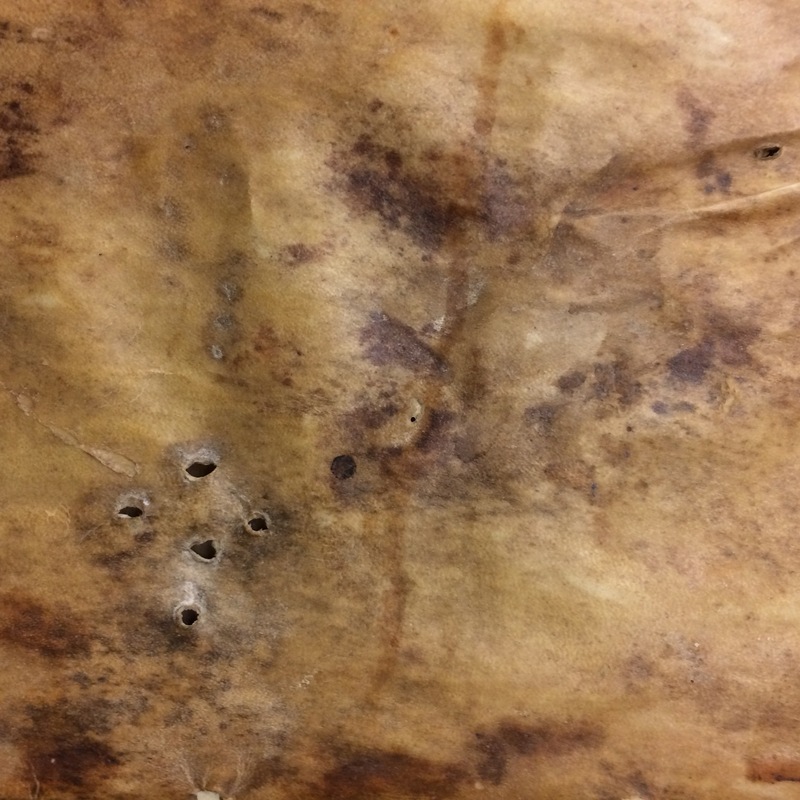

Figure 2.1: Binding holes where clasp would once have been attached.

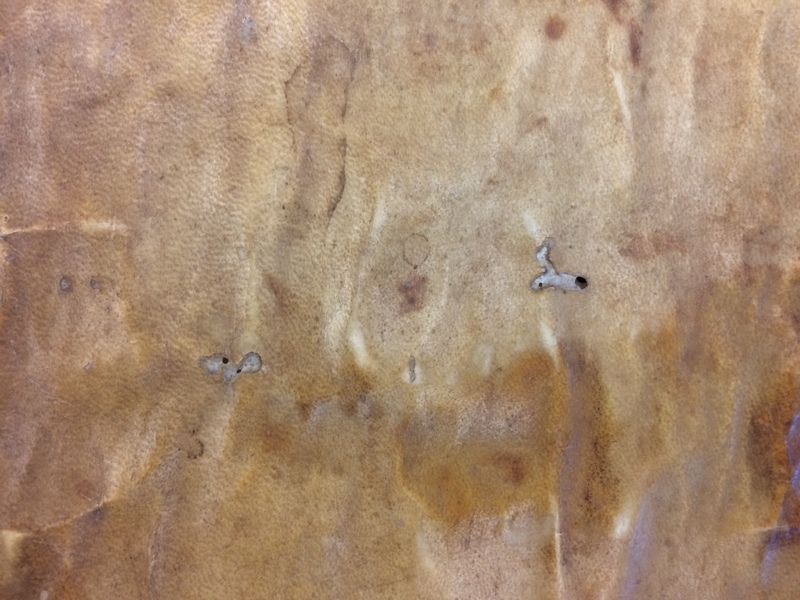

Figure 2.2: Binding holes from missing straps.

Figure 2.3: Stitched tear in the manuscript.

Figure 2.4: Worm holes.

Figure 2.5: Binding support from a medieval breviary.

Figure 2.6: Finger print in lower margins of recto folio.

Manuscript materials and wear

If the manuscript tells a part of the story of print culture by indicating the traditions from which print culture sprang, the ageing of the manuscript itself tells a more microscopic version of that narrative. Binding holes point to what the book might have looked like at an earlier time, and also to the desire to safeguard the ideas held within. Rips in the parchment and holes eaten by book worms (woodworms) can lift the reader out of the content momentarily and remind them of its pre-existence as an animal. Binding supports hide the histories of previous manuscripts, now lost or re-used. Finger prints show pages most frequently read, and connect readers of past and present. Traces of the different phases of the manuscript’s existence show how the manuscript was used, give hints of those who used it, and even point to its pre-book origins.

Binding Holes

Holes seen in figures 1.1 and 1.2 show where a clasp might once have been attached, which would allow the manuscript to be clasped shut (Les Eluminures). Clasping the book shut would help keep it safe from wear and tear, especially if it were carried around. Both the manuscript’s relative lightness, due to the limp wallet binding, and the emphasis of the Third Order on conversion (Sastre Palmer) indicate that this could have been how the manuscript was used.

Rips and tears: how they're made and how they're fixed

To make parchment, workers first used a knife to scrape away as much hair as they could before submerging the animal hide in a lime solution which then loosened the remaining hair. After sitting for a couple of days, the rest of the hair would be removed, and the hide would be once again cleaned. At this stage, the hide had to be stretched while drying, at which point it was possible for the skin to tear (Clemens 9-12; Medieval and Early Modern Manuscripts 9). Since the making of parchment was a time-consuming endeavour, and the finished product was, as a result, an expensive commodity, less expensive manuscripts often included pages with rips that had been stitched together, or holes which the scribe wrote around (Clemens 12-13). The lower margins of figure 2.3 show where a folio in Regla de la Sagrada Orden has been stitched together after a tear.

Wormholes

Holes in the manuscript can also appear because of woodworms, as is the case in the front cover of the Regla, seen in figure 2.4. Wormholes are generally easily distinguished from holes due to tearing during the drying process, because tears allow the scribe to write around the hole, whereas wormholes often eat through text. Often, these worms burrow through multiple pages (Clemens 13), but luckily for us, these worms stopped after two attempts at the cover.

Binding supports

In addition to burrowing worms (or traces of them, at least), the cover of the Regla also contains a piece of what appears to be a medieval breviary burrowed into the binding to act as a binding support. Such binding supports were sometimes made from new pieces of parchment, but they were frequently taken from scraps in which the scribe had made an error, or from old manuscripts (Clemens 51). The breviary fragment found in Regla (figure 2.5) is from a much earlier manuscript, and has been dated broadly to sometime between the twelfth and fourteenth century (Les Eluminures), but the script indicates it is likely from after the twelfth century. Most of the text is, of course, covered, but the visible words: “et continuis tribulationibus laborantem propitius respirare” reveal its former life in a medieval breviary.

Traces of the readers left behind

Just as the wrinkling of the parchment and the presence of hair follicles remind us of the animal that existed before the book, finger prints left in the margins of folios with heavy use (such as those in figure 2.6) point to the readers who came before. The manuscript is therefore both object and container in a way that is perhaps more obvious than is a printed book. All this metadata functions to tell a miniature history of the book, in its development from animal to object, from ideas to words, and from one method of textual organisation to another.

The Text as an Organisational Tool to House and Situate Ideas

Catchwords

To assist in the binding process (manuscripts were written in generally before they were bound), catchwords, also known as “stitchwords,” would sometimes appear at the end of a quire to indicate the word, or words, that should follow on the next folio so the manuscript would be bound in the right order. In MS.Span.1, the word “muy” in the lower right margins of the verso folio seen in figure 4.1 indicates the first word on the following page.

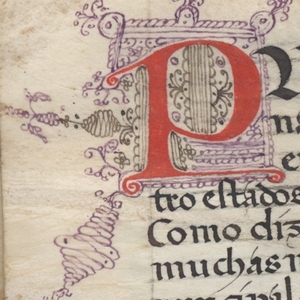

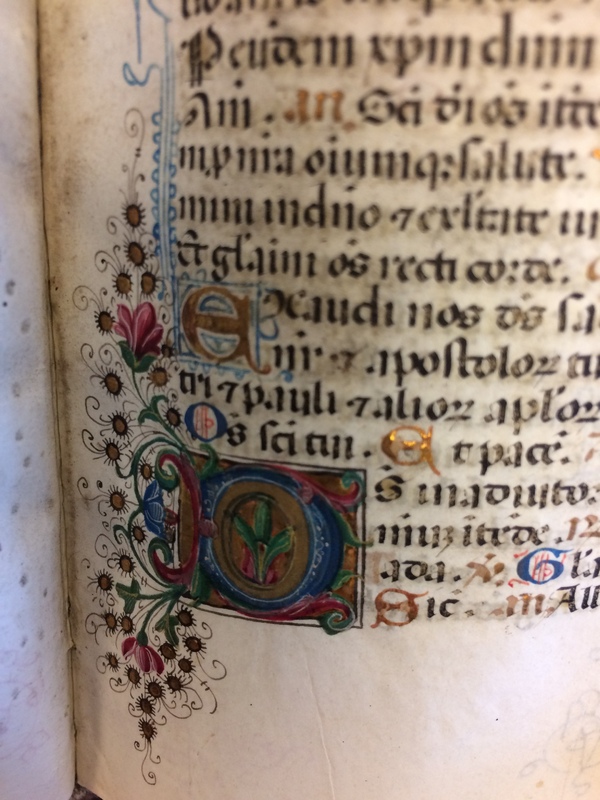

Initials

Enlarged or decorated initials, letters which were often rubricated and decorated in pen flourishes, served to draw the reader’s attention to a particular section, including (but not limited to) the beginning of a new chapter (such as the decorated capital P in figure 4.2). They were partly used to decorate the manuscript, thus adding to the book’s overall value (to different degrees, depending on how elaborately the initial was decorated). Some initials, called “historiated initials,” incorporated elaborate pictures of humans and scenes while others were merely rubricated, or included minimal vine-like designs (Clemens 27). Some were illuminated with gold or silver leaf, and others were decorated with ink. Initials appearing in the middle of a passage of text could be enlarged (while remaining plain) to point to an important section or word. Folio 5r from the Regla contains the word: “clemens” (figure 4.3), the Latin word for “merciful,” in enlarged capitals.

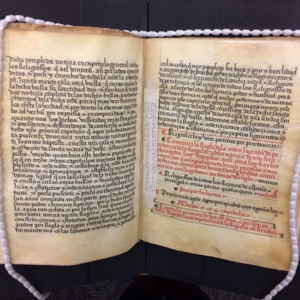

Rubrication

In addition to decorating initials, as seen in figure 4.2, rubrication was used in a variety of ways, but it generally served to direct the eye to important sections of the work, especially the beginning and the end (Clemens 24). Rubrication sets sections apart when it contrasts with black ink (or ink of another colour) text. Figure 4.4 shows the alternating use of rubricated and black paraphs immediately followed by text of a contrasting colour. The first rubricated text here announces the beginning of the Rule (after the preface) and, notably, the closing border design which follows this text is black. Latin often appears in rubrication, as in the manuscript’s opening text (“In Dei nomine amen”), and here, in the words: “Incipit foelicites," Latin for "beginning very happily." The following quote from Matthew is in black text, again, to aid the eye by contrast, and it is then cited in rubrication. As is the case with all the chapters in the manuscript, the words announcing the first chapter at the bottom of the page are also rubricated.

A Humble Container for Religious Text

The following transcription, taken from the first chapter of the manuscript, captures well both the humble, penitent life of the Third Order Regular and the seriousness with which the order conducted itself. I have elected to maintain the Early Modern Spanish spellings in my transcription, but have added punctuation to facilitate better comprehension. My many thanks to Adrienne Williams Boyarin for assistance with transcription concerns and general manuscript detective work, and to Pablo Restrepo-Gautier for his help on a particularly puzzling translation issue.

Modified Transcription

Primeramente ordenamos, y establesçemos, y declaremos que en esta sagrada orden de penitencia aya quatro estados, y differnçias, y maneras de Religiossos. Como dize el euangelio: “En la casa de mi padre ay muchas moradas.”

Y sea en este modo que el primero, y principal, y mas perfecto estado sera de los frayles y monias que biuen en casas y conuentos, colegialmente prometiendo los tres votos essemçiales. Conviene a saber obediençia, castidad, y pobreza en particular. Los quales votos prometeran de aqui adelante, y acuerdense de aquello que dize el sennor en el sancto euangelio, dandonos doctrina como le auemos de seguir. Dize: “Si quisieres ser perfecto, ve y vende lo que tienes, y dalo a los pobres, y ternas tesoro en el cielo, y ven y sigue me.” Y dize mas: “Si alguno quisiere venir empos de mi niegue asi mesmo y tome su cruz, y siguame.” Y los tales frayles deste primer estado an de ser, y sean sacerdotes, exçepto aquellos que los conuentos tienen, y tuvieren, para seruiçio de sus casas, y yglesias, y personas.

El segundo estado, de hermitannos, los quales en hermitas y hiermos seguiendo la vida hermitica a inmitacion de los padres del hiermo de tierra de egipto, los quales asi mesmo, al tiempo que hizieren profession, hagan y prometan los dichos tres votos essemçiales.

El tercero estado, de biudos continentes y beatas y otras quales quier personas que deste habito y profession andan vestidos. Los qualles prometan voto de obediençia a sus perlados, y voto de castidad, y los mandamientos diuinos.

El quarto estado, de coniugados, los qualles ansi mesmo prometan voto de obediençia a sus perlados y voto de castidad coniugal y los mandamientos divinos en tal manera que haziendo profession en este estado qualquier dellos que la hiziere no pueda despues de disuelto el matrimonio por muerte de alguno, tornarse acasar, sino que permanezca para siempre en el terçero estado de biudos continentes.

Los qualles todos quatro estados, su sanctidad, por la dicha su bulla ultimamente a esta orden conçedida, quede su sova declarada, declara por verdaderos frayles, y Religiossos, y monias Religiossas, de la dicha orden sagrada de penitençia, y por verdaderos hiios de nuestro padre, sant françisco, para que portales sean auidos y tenjdos. Gozen im perpetuum de las graçias indulgençias, y perdones, y libertades, inmunidades, exempçiones y preuilegios conçessos et conçedendos imposterum ala dicha orden, y a las ordenes mendicantes, y sancta clara, y nos el dicho fray Antonio de Tablada, vissitador y ministro general, y presidente, y diffinidor es en este capitulo, por esta nuestra Regla y declaraçion, Respectiue por el poder a nos conçedido. Portales los auemos y diputamos y declaramos agora y dende aqui adelante para siempre iamas. Esta declaramos ser la verdadera intelligençia de la dicha bula y de su sanctidad que la conçedio.

Translation

First we decree, and establish, and declare that in this sacred penitential order there are four states and different kinds of religious persons. As the gospel says: “in the house of my father there are many dwelling places.”

And let it be in this way that the first and principal most perfect state will be of the monks and nuns who live in houses and convents together, promising the three essential vows. It is advisable to know obedience, chastity, and poverty, in particular. They will swear these vows from this time forward, and remember that which the Lord says in the holy gospel, giving us doctrine that we should follow. He says, “If you would like to be perfect, come and sell what you have, and give it to the poor, and you will have riches in heaven, and come and follow me.” And he says more: “If anyone wants to come after me, deny yourself and take up your cross, and follow me.” And those brothers of this first state must be, and should be, priests, except for those that the convents have and would have for servants of its houses, and churches, and people.

The second state, of hermits, who in hermitages and wastelands pursuing the hermitic life in imitation of the fathers of the desert of the land of Egypt, who like this, at the time that they take their vows, carry out and promise the aforementioned three essential vows.

The third state, of chaste and blessed widowers and whoever else who go clothed in this habit and way of life, those who promise their vow of obedience to their prelates and vow of chastity and the commandments of the divine.

The fourth state, of married persons, precisely in this way promise vows of obedience to their prelates and vows of conjugal chastity and of the divine commandments in such a way that, taking vows in this state, whosoever does it cannot afterwards dissolve the marriage through the death of either, or marry again, but must always remain in the third state of chaste widowers.

All such four states, His Holiness (by the said papal bull recently granted to this order in its declared penitence) will declare for the true monks and religious persons, and religious nuns of the aforementioned holy penitential order, and for true sons of our lord, Saint Francis, so that doorways are opened, and held open. Delight for eternity in the merciful indulgences, and pardons, and freedoms, immunities, exemptions and privileges, concessions and allowances in the hereafter, in the said order, and to the mendicant orders, and St. Clara, and Fray Antonio de Tablada, who is the visitor and general minister, and president, and definer in this chapter, by this, our Rule, and declaration, respected by the power granted to us. We have validation, and we delegate and declare here and now, from this time forward, for ever and ever. This we declare to be the true intelligence of the said (papal) bull, and of his holiness that granted it.

Figure 5.1: Decorated initial: rubricated capital letter A, decorated in black ink.

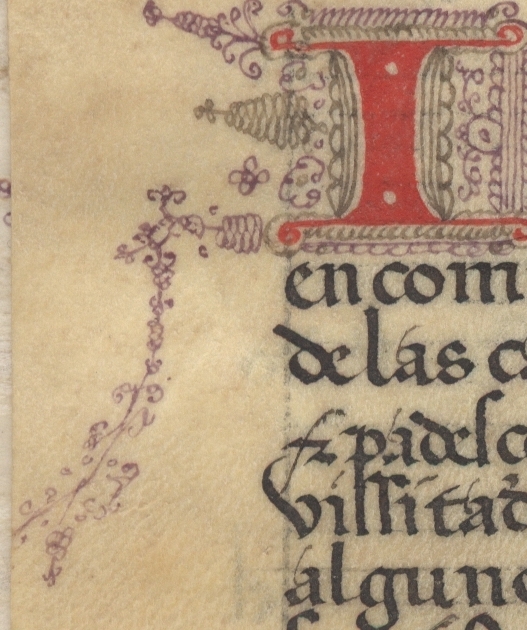

Figure 5.2: Decorated initial: rubricated capital letter I, decorated in purple and black ink.

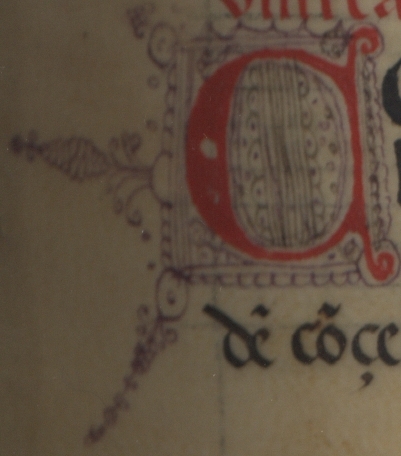

Figure 5.3: Decorated initial: rubricated capital letter C, decorated in purple and black ink.

Figure 5.4: Decorated initial: rubricated capital letter O, decorated in black ink.

Figure 5.5: Decorated initials with gold leaf from Codex Pollick.

Figure 5.6: Historiated initial from Codex Pollick.

Decorated Initials

The initials in Regla de la Sagrada Orden de Penitencia, as can be seen in figures 5.1 through 5.4, are decorated with varying degrees of ornamentation. Some are relatively simple in their pen-flourishes, as in figures 5.1 and 5.4, while others, such as the letters in figures 5.2 and 5.3, have more extensive flourishes which spill into the margins and include two colours of ink (black and purple). The initials seen in figures 5.5 and 5.6, by contast, are from University of Victoria MS.Lat.3, or, Codex Pollick, and feature similar pen flourishes, but include gold leaf, and beautiful historiated initials.

The Codex As a Spiritual Tool: End Prayers For the Scribe

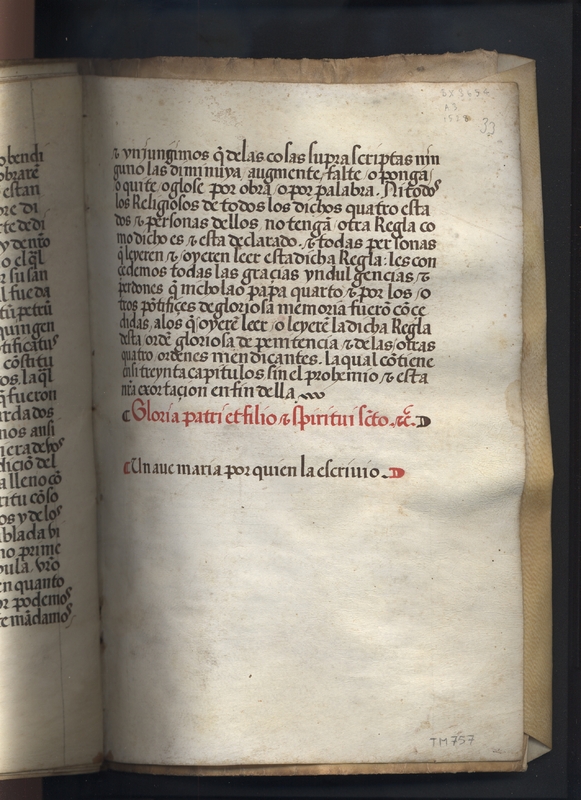

Although scribes did not always sign their names during this period, they would sometimes end their work with a request that the reader pray for their souls (Clemens 117), as is the case in Regla de la Sagrada Orden. Here, the scribe offers two prompts to prayer. As seen in figure 6.1, the first line to the “Gloria Patri” (“Gloria patri et filio et spiritu sancto,” or, “Glory to the father, and the son, and the holy spirit.”) appears in rubrication. Following this, the scribe returns to the Early Modern Spanish that characterises the majority of the manuscript, prompting the reader to pray for him: “Un aue maria por quien la escriuio” (“a Hail Mary for he who wrote it”). Unfortunately, our scribe does not name himself, as some did, so his identity will likely remain a mystery.

Works Cited and Consulted

Bede, Jarrett, et. al. "Third Orders." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 14. Robert Appleton Company, 1912.

Bihl, Michael. “Order of Friars Minor,” The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. 6, New York, 1909.

Breviarium Lingonense. Harvard College Library, 1926. Google Books. Accessed on 5 Dec. 2016.

Clemens, Raymond and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca; London: Cornell University Press, 2007.

The Concise Oxford English Dictionary. 8th ed. Oxford, 1990.

"Decoration and Illumination." Manuscripts and Special Collections. University of Nottingham.

Les Eluminures. "Vendor Description." University of Victoria.

Harrington, K. P. Medieval Latin. University of Chicago Press, 1969.

Latdict: Latin Dictionary and Grammar Resource.

Latin Dictionary. Babylon, 2008.

Medieval and Early Modern Manuscripts: Bookbinding Terms, Materials, Methods, and Models. Yale University, 2015.

Memoriale Propositi (English translation of the original Rule of the Third Order of 1221)

More, Alison. "Institutionalizing Penitential Life In Later Medieval And Early Modern Europe: Third Orders, Rules, And Canonical Legitimacy." Church History 83.2 (2014): 297-323. ATLA Religion Database with ATLASerials.

"Minsheu Dictionary." Early Modern Spain. King's College, 2006.

MS Span. 1. McPherson Library, University of Victoria.

Nicholas IV. Supra Montem (1289 bull affirming the Rule of the Third Order, in English)

Regla de la Sagrada Orden de Penitencia de la Nuestra Seraphica Padre Sant Francisco. Transcribed by Rachelle Ann Tan. University of Victoria, 2016.

Sastre Palmer, Nicholas. “History of the Franciscan Third Order Regular,” trans. Seraphin Conley, Franciscan Friars: Third Order Regular of St. Francis

"Spanish-English Dictionary." Word Reference. Online Language Dictionaries, 2016.

Wheelock, Frederic M. and Richard A. Lafleur. Wheelock's Latin. 7th ed., Harper Collins, 2011.

I would like to acknowledge and thank Dr Adrienne Williams Boyarin for her advice on transcription, and her help with general manuscript inquiries, Dr Pablo Restrepo-Gautier for his help with some perplexing Early Modern Spanish translation issues, and Dr Mark Nugent, for his assistance with a Latin query.

IL/Fall2016