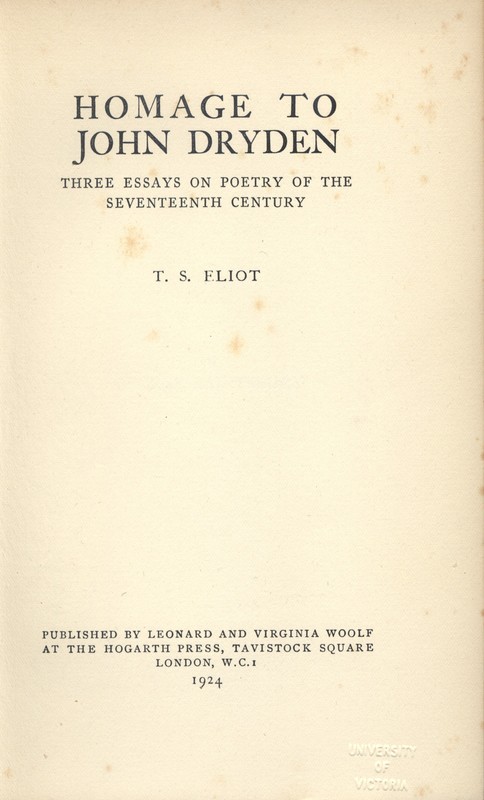

T.S. Eliot, Homage to John Dryden: Three Essays on Poetry of the Seventeenth Century (1924)

Homage to John Dryden by T.S. Eliot

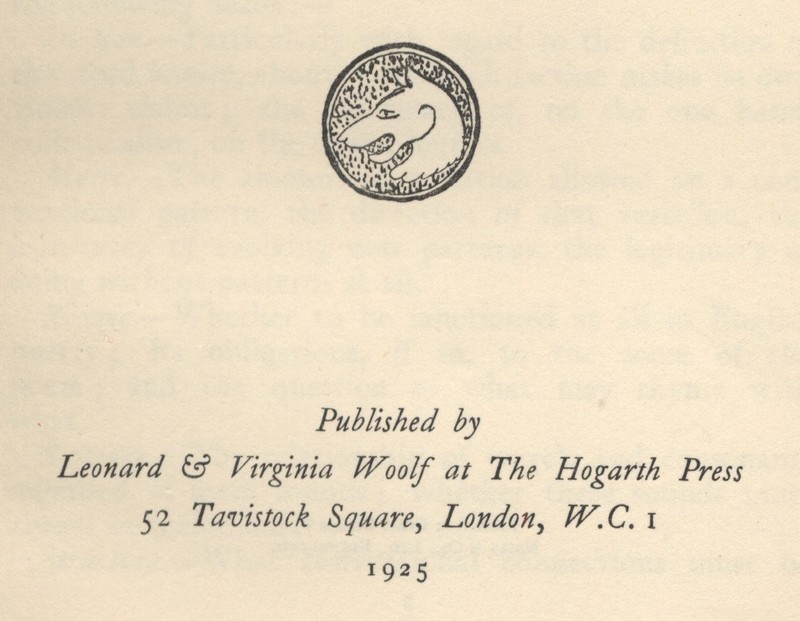

Printed by Leonard and Virginia Woolf at the Hogarth Press

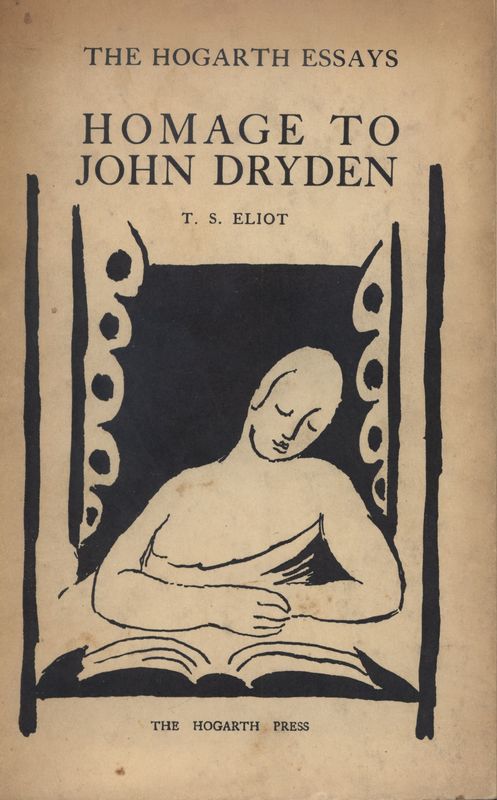

Cover Illustration by Vanessa Bell

Title Page for Homage to John Dryden published at the Hogarth Press

Homage to John Dryden: Three Essays on Poetry of the Seventeenth Century by T.S. Eliot is an intriguing work which is emblematic of many important trends that developed during the inter-disciplinary era known as the modernist period. It is evident from a thorough examination of the text that networks of all kinds were of the utmost importance during the modernist period. The text shows, through its various avenues for analysis, the multitude of connections that existed between artists, disciplines, and members of early-twentieth century society.

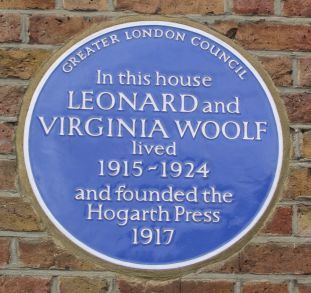

Homage to John Dryden is, on a technical level, a literary pamphlet, and was published in 1924 by Leonard and Virginia Woolf at the Hogarth Press. Tho Hogarth Press has a great deal of historical, cultural, and artistic significance, and also played a vital role in the development of modernist networks. Through its varied publications, interpersonal connections, and diverse viewpoints expressed through a range of texts, the Press was instrumental in the development of a reading public, printed English translations of many important German and Russian modernist works, and encouraged valuable discussion between contemporary thinkers and the greater reading public.

Homage to John Dryden was published as part of a series called The Hogarth Essays, a collection of pamphlets that covered a range of topics including literary criticism, politics, philosophy, history, and aesthetics. Each text was created with the intent to address the public and create a social discourse about ideas and issues that concerned members of early-twentieth century society. Eliot’s text was intended to familiarize readers with Dryden’s seventeenth century poetry, which he considered vastly superior to the work of the Romantic and Victorian poets that preceded the modernist period.

The front cover of each set of texts, as there were two series that were published throughout the Press’ lifetime, were all designed by Vanessa Bell, Virginia Woolf's elder sister. Bell was a permanent fixture of the Hogarth Press, as she designed many front covers and dust jackets, as well as provided textual illustrations, for a number of works. While some believe this to be a choice that arose out of familial ties, proximity, and convenience on the part of the Hogarth Press, there is evidence to suggest that Bell represents, for the Press and the community it created, an important tie to the avant-garde. Considered as a whole, the text is representative of the Hogarth Press' practices as a business and social enterprise, but also as a touchpoint for important trends and themes that developed during the modernist period.

The People

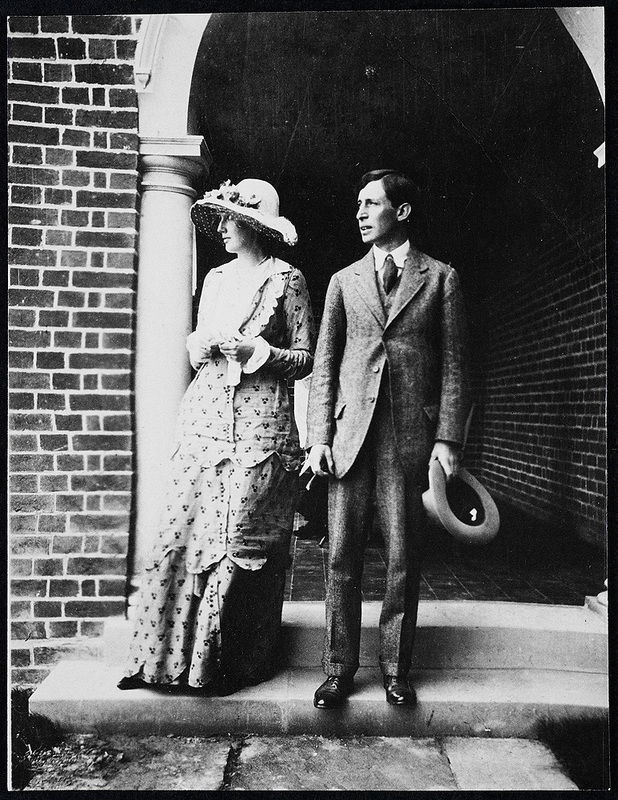

Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf is arguably one of the most important figures of the modernist era, as she, along with James Joyce, was instrumental in the development of stream of consciousness writing as a narrative form. Her contributions extend beyond the realm of fiction, though, as Woolf’s non-fiction works, such as A Room of One’s Own and Three Guineas, were incredibly important in shaping public discourse surrounding gender equality and contemporary ideas of national identity. Her contributions to the literary world are invaluable, evidenced by the fact that she remains a prevalent author in our contemporary world who is the subject of much critical study. However, Woolf’s relevance in the field of modernist studies goes far beyond her personal contributions to the world of literature.

Woolf, along with her husband Leonard, owned and operated the Hogarth Press, which is where Homage To John Dryden was first published, along with scores of other important modernist texts. The Press began in 1917 as a hobby for the Woolfs, but it quickly grew into a thriving business with a broad international and interdisciplinary scope that became incredibly significant to the modernist period.

Ursula McTaggart notes in her article on the Hogarth Press that Woolf was very hands on with regard to the day-to-day operations of the Press. Details from her diaries, in addition to employee accounts, demonstrate that she was not merely a passive overseer — she did a great deal of physical labour and hand-binding with the other workers (66). McTaggart states, “For handprinted material, Woolf stitched the bindings, and when texts were printed by outside firms, she joined servants, employees, and Leonard in packaging and shipping the finished books. John Lehmann recalls Woolf [regularly] working beside employees in overalls” (66-67).

Woolf also states in her diaries and correspondence that she was quite useless when it came to running the financial side of things, as her primary interest in the Press resulted from the creative liberty it afforded her (Woolf and Bell 55). The Hogarth Press allowed her to write and publish whatever she saw fit, while simultaneously absolving her of any concerns regarding censorship at the hands of an external editor or publisher — a fate that many of her contemporaries suffered. This creative liberty did, however, extend to friends, emerging artists, theorists, and critics that her and Leonard saw either potential or immediate cultural value in. This courtesy was extended to the author of this text, T.S. Eliot.

The Press also allowed Woolf to develop connections and friendships with a number of her influential contemporaries, such as Roger Fry, Gertrude Stein, Robert Graves, E.M. Forster, and, as stated earlier, T.S. Eliot (McTaggart 75). These relationships may have occurred regardless, but the Hogarth Press provided opportunities for Woolf to work with these learned persons on a professional level.

Eventually, the work involved with running the Hogarth Press became too onerous for Woolf, so she decided to relinquish her responsibility with the business side of the press in 1938. McTaggart states that Woolf “longed for the lost privacy of her own ‘room.’ In 1937, she bemoaned the publicity required by the Press” (67). Additionally, “the realities of the Press's daily needs became difficult for Woolf. During her moments of dissatisfaction, she expressed to friends or her diary that she hoped to sell it” (67). While Woolf enjoyed the creative liberties the Press afforded her, it simply grew to be too much work.

Leonard Woolf

Once Virginia Woolf chose to extricate herself from the commercial side of the Hogarth Press in 1938, Leonard brought on John Lehmann, whom Virginia had sold her stake in the Press to, as a partner in order to have someone help him run the business (McTaggart 66). Donna Rhein notes in her lengthy study of the Hogarth Press that Leonard remained very hands on, doing much of the physical labour involved with publishing himself, and continued to influence what was published there throughout his lifetime (60). However, she also states that after Virginia’s exit, the Press struggled due to the fact that Lehmann had no practical management experience; as such, focus was shifted away from hand-printing works towards publishing at the Press (7). Critics do generally agree, though, that Leonard had a greater influence with regard to the daily workings of the business, “as he fastidiously maintained the business accounts and managed the Press's employees” (McTaggart 66).

While Virginia Woolf’s works were undoubtedly more commercially successful, and have also experienced longevity in the realm of critical study, she was not the only Woolf interested in the Press as a means to retain creative freedom; Leonard printed a number of works at the press, though his texts were primarily concerned with politics and literary criticism (Rhein 1). Leonard saw the Hogarth Press as more than a hobby, as it allowed him to expound his opinions and views to the public.

Leonard’s contributions to the Hogarth Press are also what made the text at hand possible, as literary and political pamphlets, which is the category that Homage to John Dryden falls under, were his idea. Melissa Sullivan explains in her study on the Hogarth Press that "Leonard found the Hogarth Press pamphlets [to be] a unique way of introducing the British reading public to otherwise obscure thoughts and ideas in modern literature, poetry, art, philosophy or history” (60). Leonard wanted to create a public discourse surrounding topics he believed were culturally relevant, and saw inexpensive pamphlets as the answer.

Leonard is obviously not a cultural icon in the same manner as Virginia Woolf, but he was instrumental in the Press’ success, which consequently had a significant impact on the modernist era as a whole. Without Leonard Woolf, there would have been no Hogarth Press, and the history of modernism as we know it would be drastically different.

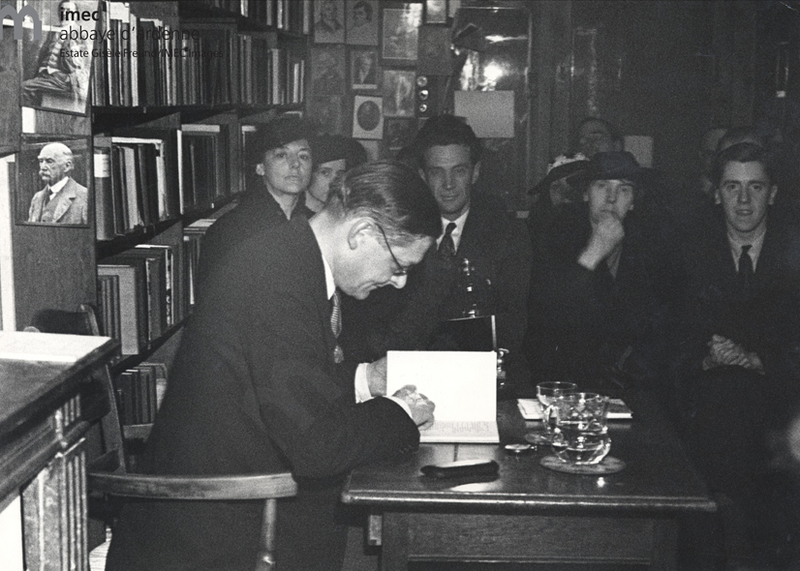

T.S. Eliot

T.S. Eliot is another incredibly important figure for literary modernism. As Joseph Laurence Black, editor of the Broadview anthology of British literature, states, “the poetry and prose of T.S. Eliot probably did more than that of any other writer to transform the face of twentieth-century English writing” (442). The Waste Land, which was printed at the Hogarth Press in 1923 (Rhein 23), was revolutionary in both form and content, and embodied many paradoxes that characterized the age (Black 442). These traits extend to the majority of his other writing, “which [decisively] established him as the voice of a disillusioned generation” (443).

Eliot’s collection entitled Poems was the first of his texts to be printed at the Hogarth Press in 1919, but it was far from the last work he had published there. The Waste Land, which had previously been printed in the periodical founded by Eliot called Criterion, was printed in book format for the first time in 1923 by Leonard and Virginia Woolf (Rhein 23). This was a significant achievement for the Hogarth Press; it increased their prestige as a press, established them as a major contender in the printing world, and helped them gain popularity and appeal amongst the European reading public (24). Up until this point, as Nicola Wilson puts it, the Hogarth Press may have suffered from a public perception of “supposed insularity as a small, independent publisher which shunned the tastes and desires of the substantial middlebrow bookselling world. This may be true of the Hogarth Press in its infancy, but this image becomes ahistorical” when you consider the fact that they printed works, such as Eliot’s, that had a wide appeal throughout the world of English literature (256). The benefits were not solely on the side of the Woolfs, though, as the printing of Poems in 1919 helped to encourage Eliot, who was currently at work on other poems, to continue writing (Rhein 24).

However, Eliot and the Woolfs were far more than mere mutual beneficiaries of a successful business relationship, as “the Woolfs came to regard Eliot as one of their best friends. Publishing his poems was one of the highlights of this friendship and of the Woolfs' printing and publishing experiences” (Rhein 22). The Woolfs had the utmost respect for his perspectives on art, culture, and literary criticism, which is arguably why Homage to John Dryden was included in the first series of the Hogarth Essays in 1924, as they believed Eliot’s thoughts were worthy of a wider audience.

It is unclear whether or not the Hogarth Press had any vested interest in the poetry of John Dryden, as Homage is the only publication from the Press that analyzes his works in any in-depth way, but Eliot clearly had a profound affinity for his work. Eliot’s interest in Dryden stemmed, in large part, from his distaste with Romantic and Victorian Poets. As Eliot states in the preface to Homage, “I have long felt that the poetry of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, even much of that of inferior inspiration, possesses an elegance and a dignity absent from the popular and pretentious verse of the Romantic Poets and their successors” (197). He believed that Dryden was the “ancestor of nearly all that is best in the poetry of the eighteenth century” (199), and that only once we gained a mastery of his work would we be able to appreciate the immense body of work generated by his contemporaries (199-200). Eliot saw in Dryden a genius and sensibility that was unparalleled by any poet of the 19th century.

These proclamations are also indicative of Eliot’s modernist tendencies with regard to manner in which he conceptualizes poetry. Eliot’s poetry is characterized by a move away from Romanticism, an appreciation for history and the metaphysical poets, a departure from established conventions of form and content, and allusions to works that he finds important to the development of literature as a field of study (Black 442-43). For Eliot, Dryden represents the highest form of satire, the expression of thoughts in a precise and concentrated manner, and language that reflects natural speaking rhythm (Eliot 202). Eliot’s fondness for Dryden is significant when considered in the context of his poetics, as he declares in “Tradition and the Individual Talent” that writers, and readers for that matter, ought to be well versed in literary history and tradition (Black 465); art needs to be understood in the context of what came before it and what surrounds it, as it never exists in a vacuum. Eliot also saw poetry as an escape from emotion, rather than a turning loose of it (465). As the editors of the Broadview anthology state, “Eliot’s introduction of these ideas to the literary world helped pave the way for the critical approach known as ‘New Criticism’” (443).

Eliot’s theories regarding literary criticism and his approach to writing denote the importance of networks and connections, and his relationship with the Woolfs, as well as the community he was a part of with the Hogarth Press, support this idea.

Portrait of Vanessa Bell, 1902

Portrait of Vanessa Bell and Virginia Woolf as children

Hogarth Press Logo Designed by Vanessa Bell in 1925

Vanessa Bell

Vanessa Bell, Virginia Woolf’s elder sister, was a painter and illustrator whose oeuvre is described by many critics as abstract, impressionist, and post-impressionist. Her subject matter ranges from modest scenes extracted from her personal life to pieces that challenge and critique social norms, such as the role that women are expected to play within society. A number of her works are characterized as conversational pieces (Brockington 141), which speaks to an important theme that developed during the modernist period: that of discourse. Well-informed discourse and open-minded conversations regarding issues that faced the public were of incredible significance during the modernist era, especially with right-wing political ideologies on the rise in many European countries. This concept was also highly valued by those involved with the Hogarth Press; Leonard and Virginia Woolf, as well as the artists and intellectuals who had their works published there, were devoted to the promulgation of valuable discussion within society.

Bell is perhaps most well-known for her membership to the Bloomsbury group, which was a group of artists, writers, and intellectuals who worked or studied in the Bloomsbury area of London during the early-twentieth century — Virginia Woolf and Leonard Woolf were also members. While some critics, as Tony Bradshaw states, “have used (or, rather, abused) [the term] indiscriminately to describe almost anyone in intellectual London between the wars” (9), the Bloomsbury monicker was, in reality, “the denomination given to a group of intimate friends, drawn together through university and family connections, who… gathered at the house in Gordon Square” (9). Despite the group’s humble origins, they had a significant impact on early-twentieth century society. The Bloomsbury group's perspectives on literature, criticism, and art greatly influenced public discourse with regard to these topics. Additionally, their works helped shape public perception surrounding ideas such as feminism, pacifism, and economics.

There are some critics who denounce Bell’s importance to the Bloomsbury group, and to modernist art in general, as they believe she was only associated with these influential artists and thinkers as a result of proximity. Grace Brockington sums up these arguments in her article on Vanessa Bell when she states, “the story has been that her technique was amateur…, her modernism derivative…, her ideas wilfully apathetic…, and her vocation compromised by family responsibilities. There is an impression that she fails the quality test, even if it is not her fault” (129). However, Brockington argues that Bell’s career as a painter “made an original contribution to European modernism, and that her art was an acute intervention in the critical debate about modern art” (130).

As stated earlier, Bell’s conversation pieces are indicative of a trend that was of the utmost importance during the modernist period: a commitment to open discourse. As Brockington argues, Bell’s conversation paintings establish discourse as “the method for working out new, ‘revolutionary’ ideas, and friendship the model for a freer, more egalitarian society” (141). The notion of its necessity, too, was not limited to a discussion between fellow artists and critics, but extended, as will be shown later, to the greater public. In this way, Bell’s paintings are emblematic of a defining feature of the age (138).

Vanessa Bell was also incredibly important to the Hogarth Press. As Helen Southworth notes, Vanessa Bell typically influenced the visual design of the books printed there, and she famously designed the first dust jacket ever done by the Hogarth Press for Woolf’s Jacob’s Room in 1922 (198). Furthermore, every Virginia Woolf text published at the Press from there on out, apart from Orlando and Letter to a Young Poet, was accompanied by a Vanessa Bell dust jacket (Willson Gordon 72). Bell’s contributions did not end there, though, as she regularly did in text illustrations and designed covers for a multitude of works produced by other artists and intellectuals, many of which were responses to political and social issues of the era (Southworth 198). These dust jackets “drew on a mixture of styles and… were difficult to pin down and categorise. Some books were more akin to fine printing, some moved towards convention, and others, like much of the material contained within them, looked, and were, experimental and even avant-garde” (198). Additionally, Bell designed the Hogarth Press’ first logo, which appeared in 1925 and depicted a wolf’s head enclosed in a medallion (194). This logo was later replaced in favour of one designed by E. McKnight Kauffer which featured “a strong, nearly abstract animal head more like a wolfhound than a wolf but unmistakably bold and modern” (194).

The cover art for Homage to John Dryden was illustrated by Vanessa Bell, and features a bold design of a woman reading. This illustration was used on a number of pamphlets from the Hogarth Essays’ first series, and new covers were devised for the later volumes of the first series. Despite some critics’ claims to the contrary, Bell was not a fixture of the Hogarth Press due to proximity, familial ties, or convenience. She represented an important connection to the avant-garde, added to the interdisciplinary nature of the press, and contributed to the community it sought to create.

The Hogarth Press

In 1917, the Woolfs bought a small hand-press that they learned to operate in their living room as a hobby (Southworth 1). The Hogarth Press, as it was named shortly after, quickly grew into a flourishing commercial enterprise (1). In its infancy, the Press was merely a tool that allowed Virginia and Leonard Woolf to exercise creative liberty, but it served a much larger purpose when the overall trajectory of Virginia Woolf’s career is considered. As McTaggart argues, the Press essentially allowed Woolf to canonize herself (71). The early days of the Press experienced fairly small readership (Jaillant 121), but as notable artists, such as T.S. Eliot, began to have their works published with Leonard and Virginia, the Hogarth press became a major publishing house with a list of appealing titles and an aggressive marketing strategy (122). Their success is also due, in large part, to the quality of the books they printed. While they never completely mastered the technique involved with printing, they created books that were meant to be easily read (Rhein 5). They also chose not reprint classics in new, aesthetically appealing editions, as many other small presses did, “[insisting instead] that content should precede material aesthetics, and by focusing on living, avant-garde authors, the Hogarth Press generated a literary and political conversation instead of beautifying personal libraries” (McTaggart 64).

Some critics believe that the Hogarth Press abandoned its humble roots and became fundamentally highbrow, but as Lise Jaillant asserts, the Press can neither be reduced to its origins as a hobby, nor can it be classified solely as a highbrow publishing enterprise (121-22). In an attempt to connect and start a discussion with the vast majority of the reading public, the Hogarth Press printed an array of contemporary voices with varied opinions about society, politics, criticism, and art. As Nicola Wilson puts it, “despite its reputation for independence and the avant-garde and Woolf's oft-quoted comments in her diaries about the artistic license it gave her, the Hogarth Press still needed to publish books that would sell and appeal to the average reader” (247). They toed the line between low and highbrow content, aimed to connect with the public, and wanted to encourage well-informed discourse. The Press was fundamentally centred on an exchange of ideas (McTaggart 67).

Ursula McTaggart argues in her article that the Hogarth Press was also a manifestation of sorts of an organization called “The Outsiders’ Society” that Woolf introduces later on in her 1938 text Three Guineas (65). McTaggart states that “The Outsiders' Society was Woolf's imagined means of piecing together a multiplicity of private actions to exert political influence, and though the organization never came to life, the Hogarth Press both prefigured and arguably influenced Woolf's vision of this political strategy by challenging both male-dominated literary history and nationalistic patriarchy” (65). This community of outsiders was able to critique the society in which they found themselves, and offered alternative viewpoints to the greater public that often contradicted the ideas that were being espoused by mainstream media. Woolf believed the public news media gave voice to “salacious and pompous [ideals] that supported patriarchal attitudes and righteous, often nationalist, violence” (73). But, ”because the Hogarth Press was detached from mainstream publications, artists [were able] to use this alternative social forum to pursue their work on literary criticism and language and participate in conversations on modern literature and culture with the leading figures of the day” (Sullivan 60). In addition to the obvious networks and relationships forged between contemporary artists and intellectuals, the Hogarth Press developed and encouraged networks between members of society from various walks of life, and initiated a discourse that undermined the violent, sexist, and nationalistic notions being put forward by other publications.

The Era

The period of time in which the Hogarth Press opened its doors was one characterized by flux and uncertainty. The world was still reeling from the effects of WWI, and as a result of such a traumatic event, large groups of people began to question the validity of traditional values and hierarchies (Black XXXVIII). As Joseph Black puts it, “the intellectual underpinnings of twentieth-century modernist literature are intimately connected with the ideas of philosophers of language such as Bertrand Russel, the social philosopher Karl Marx, and of the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud (XXXVIII). The ideas espoused by public intellectuals such as these led to many of the conventions we associate with modernist art and literature. One such example is the development of ‘stream of consciousness’ writing as a narrative form, which was largely derived from the psychological theories of William James (XXXIX). Modernist art tends to embrace multiplicity, assert the unreliability and instability of language, and advocate individualism over collectivism (XXXIX). This last feature is likely a response to the rise of communist and fascist ideals in a number of European countries.

The turmoil and instability found in much of modernist art is directly reflective of the society in which it was conceived. As stated earlier, fascism and right-wing political beliefs were cropping up in various European countries, and women were still largely considered second class citizens. In response to this, the Hogarth Press established a wide, politically effective range of articulations that sought to undermine these oppressive ideals (McTaggart 76). At this point in history, the reading public was as large as it had ever been, and the Hogarth Press took advantage of this by printing works they knew would engage the public. Their goal was to spark a dialogue between members of society who would not normally interact with one another. It is out of this social and political climate that The Hogarth Essays series emerged.

Homage to John Dryden: Three Essays on Poetry of the Seventeenth Century

Homage to John Dryden: Three Essays on the Poetry of the Seventeenth Century is part of a series published by the Hogarth Press in 1924 called The Hogarth Essays. The goal of the series was to offer the reading public an inexpensive, yet intellectually stimulating, piece of literature that would keep them informed with what was currently happening in the worlds of politics and art. Pamphlets printed at the Hogarth Press were inexpensive, they covered a wide variety of topics, but they still retained the high quality paper and content that the Press was known for; much of the Press’ political sway came from its pamphlet series. As McTaggart states, “pamphlets, the Woolfs believed, were a crucial means of fostering cheap and widely accessible topical discussions” (66). She goes on to say, “The Woolfs used the Press to challenge imperialism by addressing urgent political questions. Emerging as it did in 1917, mired in the international upheavals of World War I and the Russian Revolution, the Press engaged international politics with special urgency” (76). Those involved with the Hogarth Press evidently sought to connect the greater population to ideas and individuals they believed to be culturally relevant. It is fitting that T.S. Eliot’s collection of essays belongs to this series, as he was one of the most influential poets and literary critics of his time. While Homage to John Dryden does not espouse a political viewpoint or make any claims about the manner in which society ought to function, it is indicative of the route literary criticism was headed during the modernist period. Homage asserts that writers and readers of literature need to know the literary tradition from which they emerge, an idea that Eliot, as well as other critics of the age, firmly proclaim to the public.

There were two series of Hogarth Essays produced, each with a different cover design by Vanessa Bell. Homage belongs to the first series which began printing in 1924, and the second series began publication two years later in 1926.

Later Editions of The Hogarth Essays

From the First Series

Further Reading

The University of Victoria has a number of other works from The Hogarth Essays series in Special Collections. Should you wish to pursue independent research of your own, the titles and call numbers for these texts can be found below.

Henry James at Work by Theodora Bosanquet, Call No: PS2123 B6 1927

Histriophone: A Dialogue on Dramatic Diction by Bonamy Dobrée, Call No: PR6007 O354H57 1925

Anonymity: An Enquiry by E.M. Forster, Call No: PR6011 O58A634 1925

Art and Commerce by Roger Fry, Call No: N7445 F74

Contemporary Techniques of Poetry: A Political Analogy by Robert Graves, Call No: PR6013 R35C65 1925

Catchwords and Claptrap by Rose Macaulay, Call No: PE1443 M3 1926

In Retreat by Herbert Read, Call No: PR6035 E24 I6 1925

Poetry and Criticism by Edith Sitwell, Call No: PR6037 I8P57 1926

Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown by Virginia Woolf, Call No: PR6045 O72M49 1924

Works Cited

Black, Joseph Laurence, editor. The Broadview Anthology of British Literature. Broadview Press, 2006.

Bradshaw, Tony. The Bloomsbury Artists: Prints and Book Design. Scolar Press ; Ashgate, 1999.

Brockington, Grace. “A ‘Lavender Talent’ or ‘The Most Important Woman Painter in Europe’? Reassessing Vanessa Bell.” Art History, vol. 36, no. 1, Feb. 2013, pp. 128–53. Wiley Online Library.

Eliot, T.S. “Homage to John Dryden.” The Hogarth Essays, Ed. Leonard Woolf and Virginia Woolf. Books for Libraries Press, 1970.

Eliot, T. S. Homage To John Dryden : Three Essays On Poetry Of The Seventeenth Century. 1st ed., Published By Leonard & Virginia Woolf At The Hogarth Press, 1924. PR6009 L7H65 1924

Forster, E. M. Anonymity: An Enquiry. L. & V. Woolf, 1925. PR6011 O58A634 1925

Jaillant, Lise. Cheap Modernism: Expanding Markets, Publishers’ Series and the Avant-Garde. Edinburgh University Press, 2017.

McTaggart, Ursula. “‘Opening the Door’: The Hogarth Press as Virginia Woolf’s Outsiders’ Society.” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature, vol. 29, no. 1, 2010, pp. 63–81.

Rhein, Donna E. The Handprinted Books of Leonard and Virginia Woolf at the Hogarth Press, 1917-1932. UMI Research Press, 1985.

Southworth, Helen. Leonard and Virginia Woolf, The Hogarth Press and the Networks of Modernism. Edinburgh University Press, 2010. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Willson Gordon, Elizabeth. Woolf’s-Head Publishing: The Highlights and New Lights of the Hogarth Press. University of Alberta Libraries, 2009.

Wilson, Nicola. “Virginia Woolf, Hugh Walpole, The Hogarth Press, and The Book Society.” ELH, vol. 79, no. 1, 2012, pp. 237–60.

Woolf, Virginia, and Anne Olivier Bell. The Diary of Virginia Woolf. Hogarth Press, 1977.

A. P. / Fall 2018