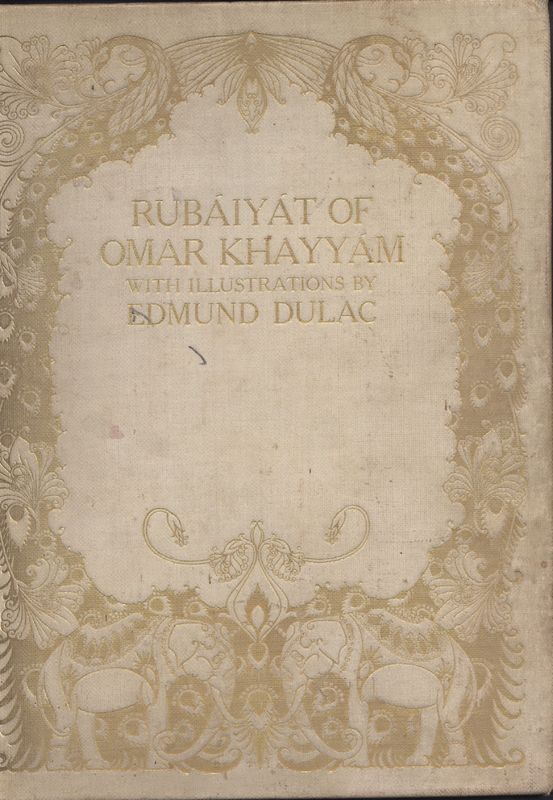

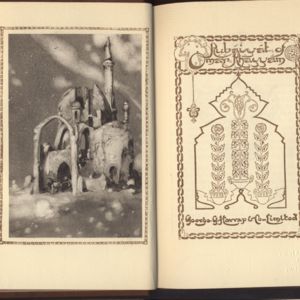

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayam-Translated by Edward Fitzgerald (Hodder & Stoughton, 1909)

Cover page of Fitzgerald's Rubaiyat published by Routledge and Sons (1912)

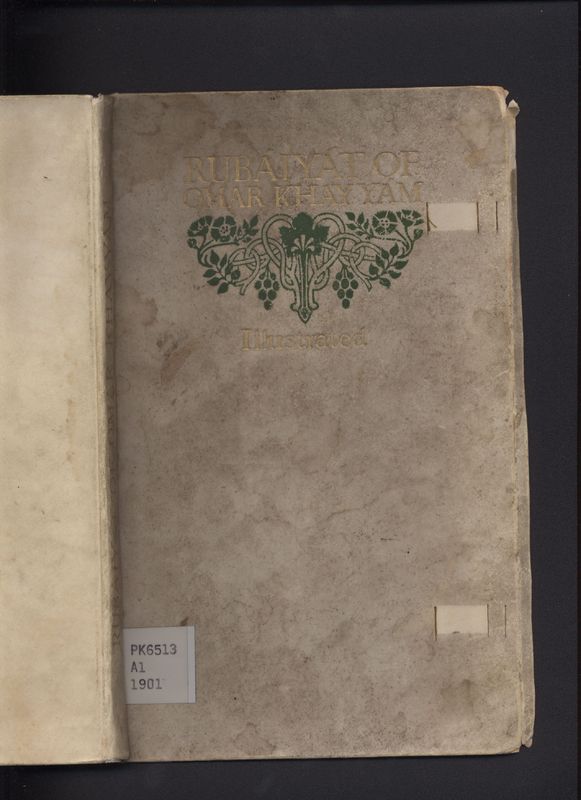

Cover Page of Fitzgerald's Rubaiyat published by John Lane (1901)

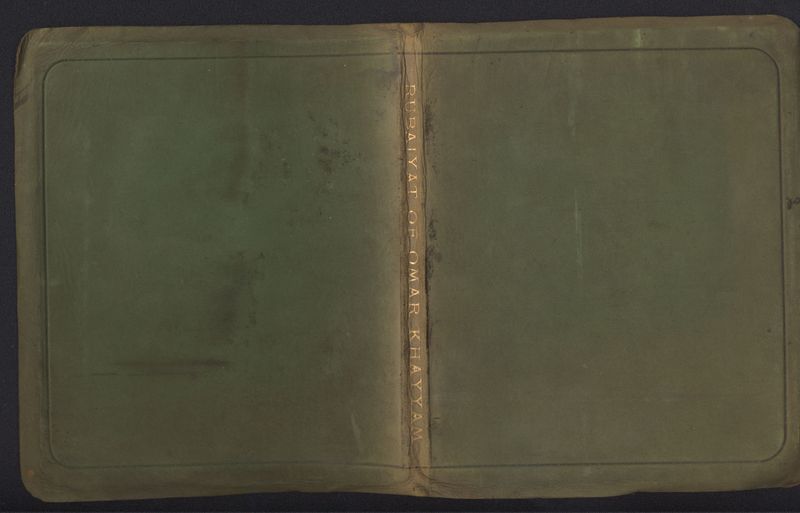

Cover page of Fitzgerald's Rubaiyat published by Siegle Hill &Co. (1911)

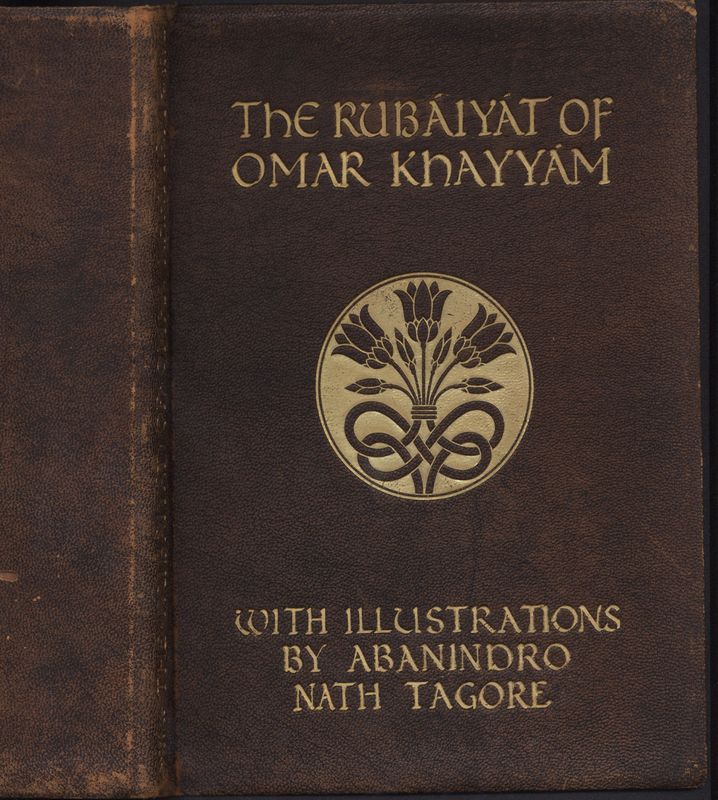

Cover page of Fitzgerald's Rubaiyat published by Leopold B. Hill (1920)

Fitzgerald's Rubaiyats in the Special Collections of the University of Victoria

There are more than twenty versions of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayam, the Iranian mathematician, philosopher and poet of eleventh century, translated by Edward Fitzgerald, available in the Special Collections of University of Victoria’s library. The earliest version is from 1879 and was published in London by Bernard Quaritch (who first published the book in 1859). Two editions were published in 1900: one, introduced by Laurence E. Housman and illustrated by Margaret R. Caird, was published by Collins' Clear-Type Press in London, and the other illustrated by Frank Brangwyn and published in London by T.N. Foulis. UVic's Special Collections also has a copy of Fitzgerald's Rubaiyat published in London and New York in 1901 by the famous John Lane publisher, with illusrations by Herbert Cole. Another edition, from 1910, has twelve illustrations by Abanindro Nath Tagore, and is printed by Eyre & Spottiswoode in London. The collection also boast a pocket 14 cm version published by Siegle, Hill & Co. in 1911 in London, which has red decorative letters at the beginning of the first line of the first stanza on each page, as well as marbled endpapers. The same publisher in the same year published an oversize illuminated version of the book with an introduction by A. C. Benson, reproduced from a manuscript written and illuminated by F. Sangorski & G. Sutcliffe. And that's not the end of the list yet. Special Collections also has an edition with 12 photgravures after drawings by Gilbert James published in London in 1912 by G. Routledge. Finally, there is a copy of the 1938 the Golden Cockerel Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám printed for the first time with translations of the Latin and Persian originals, as well as a critical essay by Sir E. Denison Ross and line engravings by John Buckland-Wright.

Most of these editions are reprinted from Fitzgerald’s translation, which was first published in 1859. A variorum edition published in 1952 by Garden City Doubleday in New York includes variations from the four editions, a biographical introduction and Fitzgerald’s famous preface that is reprinted in most of the versions mentioned above. However Special Collections also has Robert Graves’ translation, with original commentaries by the translator and Omar Ali-Shah, published by Penguin in 1972. This translation focuses mainly on the mystical aspects of Khayam’s poems and the themes that he believed were neglected in Fitzgerald’s translation.

Cover Page of Fitzgerald's Rubaiyat published by Hodder & Stoughton (1909)

Title Page of Fitzgerald's Rubaiyat published by Hodder & Stoughton (1909)

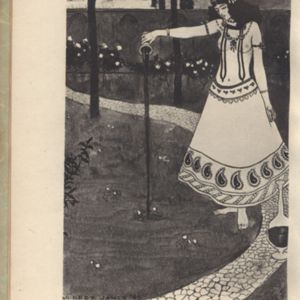

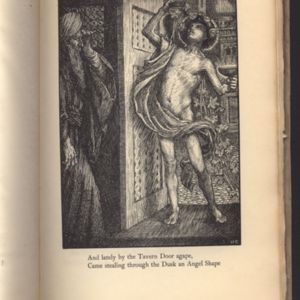

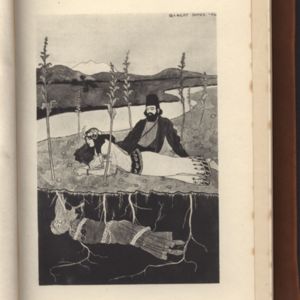

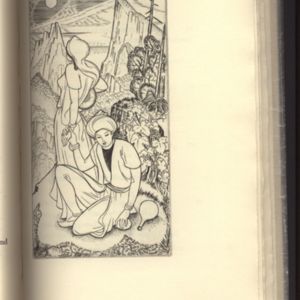

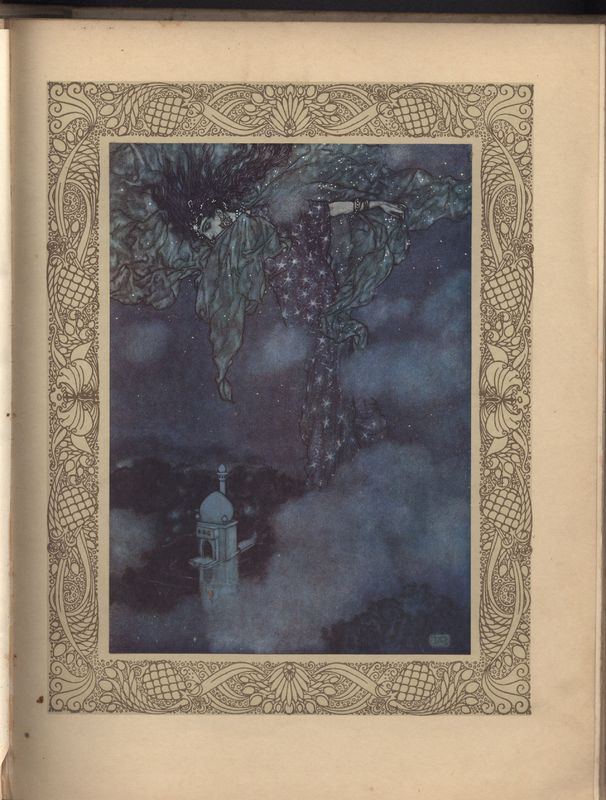

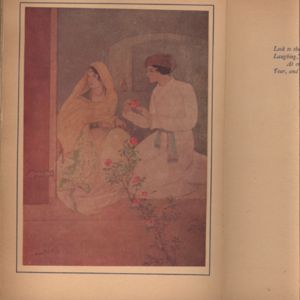

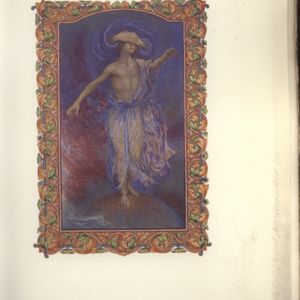

Illustration by Edmund Dulac for Fitzgerald's Rubaiyat published by Hodder & Stoughton (1909)

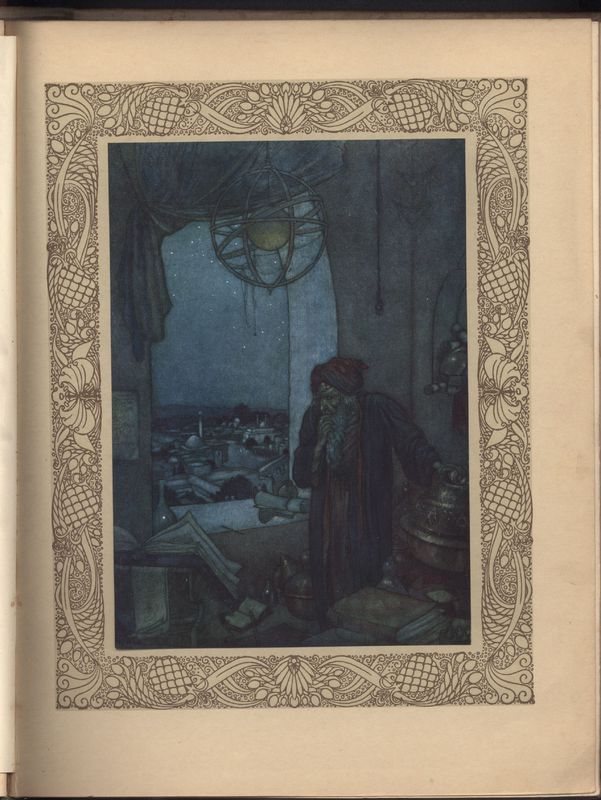

Illustration by Edmund Dulac for Fitzgerald's Rubaiyat published by Hodder & Stoughton (1909)

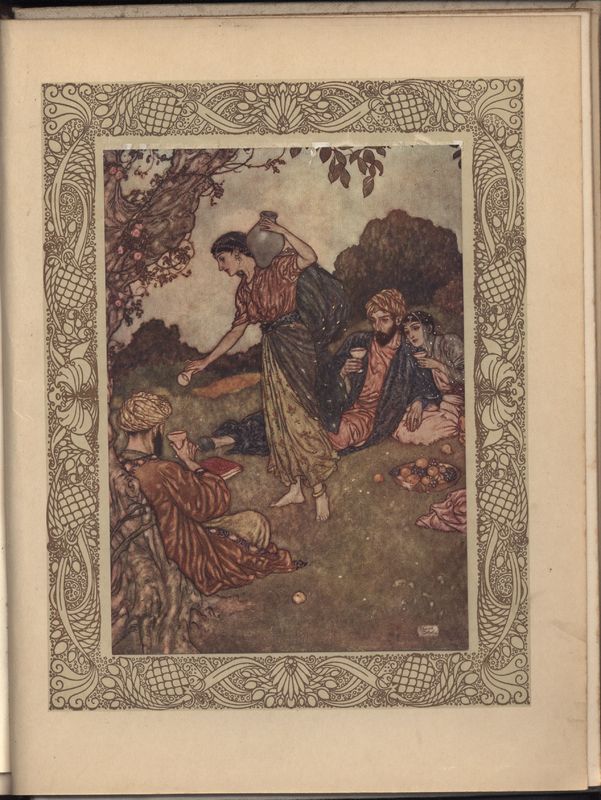

Illustration by Edmund Dulac for Fitzgerald's Rubaiyat published by Hodder & Stoughton (1909)

Hodder & Stoughton Edition

For my Omeka project I chose the Hodder and Stoughton edition published in 1909, with illustrations by Edmund Dulac that became famous and were reprinted in several other editions. It is not always easy to make connections between the illustrations and the quatrains. However the visual representation of Rubaiyat by Dulac depicts many Eastern elements and, compared to the illustrations that appear in other versions of Rubaiyat (as shown in the gallery of images at the end of this page), creates a meaningfully balanced harmony with the poems.

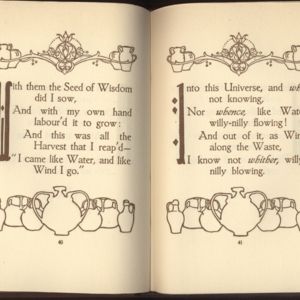

The Hodder and Stoughton edition is based on the second edition of Fitzgerald’s translation and includes 110 quatrains. The book has mounted color plates that are framed within illuminated borders. As mentioned in the library catalogue, the book is printed on one side only, excepting four preliminary leaves. The title and text are also within decorative borders; it has letter pressguard-sheets and peacock feather motif end-papers. The illustrated title page is printed in brown and sage with the designer's initials E.D. at the foot within ornaments. The second page states that the volume is “Printed from the second edition by kind permission of Messrs. Macmillan & Co. Ltd.” The book was first published in a limited edition in 1909.

Hodder and Stoughton is one of the biggest publishing groups in England. It was founded in 1868 by Matthew Henry Hodder and Thomas Wilberforce Stoughton on Paternoster Row in London. They published a variety of fiction and non-fiction books. According to their official website, their “publishing in the early years included books from Winston Churchill, JM Barrie and GK Chesterton, and The Bible. The 1920s 'Yellow Jacket' series were the precursors to the first paperbacks and included bestsellers from John Buchan, Sapper and Edgar Wallace.”

In University of Victoria's Special Collections there are many books published by Hodder & Stoughton such as Central Africa, Japan, and Fiji : a story of missionary enterprise, trials and triumphs by Emma Raymond Pitman (1882), When a man's single : a tale of literary life and My lady Nicotine by J. M. Barrie (1888, 1890) and The shadowy waters by W. B. Yeats (1900).

The Hodder and Stoughton edition of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayam, translated by Edward Fitzgerald, is based on the second edition of Fitzgerald’s Rubaiyat that was originally published in 1868. The second edition had the largest number of quatrains: 110 which was reduced to 101 in the third and fourth editions. From the 674 quatrains of the Ouselley and Calcutta manuscripts, Fitzgerald's translation was based on 75 quatrains. Norman Kelvin, in his review of the first edition of the translation explains Fitzgerald’s “rendition” of the Persian into English as follows:

He rendered Persian into English by freely adapting the Persian quatrain , the stanza known as a rubayi, into an original English language work of his own. Although his rhyme scheme was somewhat faithful to the original he used aaba and the Persian varies between aaba and mono-rhyme. He selected and arranged the quatrains to narrate a single day in the life of the persona of the poem, an arrangement for which the manuscript neither gave authority nor encouragement. (119)

Quatrains 1&2 of Fitzgerald's Rubaiyat: Hodder & Stoughton (1909)

Quatrains seventy nine and eighty from Fitzgerald's Rubaiyat published by Hodder and Stoughton (1909)

Quatrains Seven and Eight from Fitzgerald's Rubaiyat Published by Hodder & Stoughton (1909)

Fitzgerald’s Translation or “Transmogrification”

In 1859 Fitzgerald printed at his own expense the first edition of his translation of the Rubaiyat which contained seventy five quatrains from the Ouselley and Calcutta manuscripts. Bernard Quaritch published 250 copies of the book, his name appeared on the title page and the translator was not identified. The book remained unsold until Whitely Stokes, a Celtic scholar, bought one and found it fascinating. He mentioned the book to D. G. Rossetti, who took the a copy to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood literary gatherings, and the book soon started to have a wider readership. Four editions were published during Fitzgerald life time in 1859, 1868, 1872 and 1879, together with innumerable cheap, pirated or luxurious reprints that made it, according to Kelvin, “into a literary mountain” (120). This constant process of editing, and the transformative nature of Fitzgerald’s translation, has made his Rubaiyat one of the most curious cases of translated poetry.

In Nineteen Ways of Looking at Wang Wei, Eliot Weinberger maintains that “the transformations that take shape in print, that take the formal name of 'translation,' become their own beings, and set out on their own wanderings” (180). What are some of the main differences between the original poems by Khayam and Fitzgerald’s translation? Is it, as Robert Frost maintains, the “poetry” that “gets lost in translation”? Or does the cultural and historical gap between the source text and the target text create differences between the two works? Octavio Paz argues that “Each civilization, as each soul, is different and unique. Translation is our way to face this otherness of the universe and history” (159). How does Fitzgerald face this Eastern “otherness” from the distant past that has reached him in the Victorian era?

In a letter to Tennyson, Fitzgerald describes his own feeling about his poetry:

I do not care about my own verses . . . They are not original—which is saying, they are not worth anything. They may possess sense, fancy etc.—but they always recall other and better poems. You see all moulded rather by Tennyson etc. than growing spontaneously from my own mind. No doubt there is original feeling, too; but it is not strong enough to grow up alone and whole of itself. (338)

According to Christopher Decker, an editor of Fitzgerald’s Rubayiat, “there is no truer judgment on all Fitzgerald’s poetry than this, yet in the Rubaiyat he realized his genius in transfusing another’s genius, whether in translating a kindred co-author like Omar Khayam or in alluding” (217). He argues that in Fitzgerald's translation of Rubaiyat there are allusions to the works of other poets like Pope and Tennyson. He uses these literary allusions, recontextualizes them, but at the same time keeps their original state where they are in a “fond contestation” with the text , and not “called into question”. His translation uses allusions frequently and “prevails upon other poems for memorable speech without necessarily seeking to prevail over them” (218).

Decker maintains that, in Fitzgerald's Rubaiyat, “the sense of the passage is 'echoed' or imitated not by the sounds of English speech but by the act of allusion” (218). However according to Decker Fitzgerald has a different attitude towards biblical passages where he gets “aggressively revisionary” (218). The biblical allusions become part of the textuality of Fitzgelad’s work but still “striking an undercurrent of readerly memory,” which is “channeled” into the hedonistic themes of his translation.

According to Decker the recurrent image of “moulding earth” and “clay” in Khayam’s poems creates a “metaphorical relation” in Fitzgerald’s translation with the “actual reworking of verbal substance” and the “matter-moulded forms of speech” which he borrows from other poets (219). Fitzgerald describes his translation as a “transmogrification” in a letter written to his friend Cowell, a Sanskrit and Persian scholar who introduced him to Khayam through the Ouselley’s collection at the Bodleian library:

My translation will interest you from its form, and also in many respects in its detail: very un-literal as it is. Many quatrains are mashed together: and something lost, I doubt, of Omar's simplicity, which is so much a virtue in him [...] I suppose very few people have ever taken such Pains in Translation as I have: though certainly not to be literal. But at all cost, a thing must live: with a transfusion of one's own worse life if one can’t retain the original's better. Better a live sparrow than a stuffed eagle. (352)

According to Cutter, a “move from a literal to a metaphorical understanding of the process of translation” happens in translations that “involve an active participation with the source text” which are “creative and imaginative, rather than passive, literal, and constrained” (32). Fitzgerald was very obsessive over his translation and never felt satisfied with it. The philosophical depth of Khayam’s poetry led him along this long editorial process. Mark Wormald contends that the translation of Rubaiyat by Fitzgerald gave him an opportunity to respond “to what he regarded as wrongheaded recent scholarship” to show his “disdain for the kind of lazy verbosity that had unfortunate echoes in much Victorian poetry” (385). Wormald, in his review of Decker’s critical edition, maintains that each version of Rubaiyat “was a response to different pressures, biographical, aesthetic, commercial; each was the result of a different set of negotiations; each won its own devotees. And none of them ever permanently satisfied Fitzgerald” (386). The publication of the fifth edition of the book based on Fitzgerald’s marginal notes in his fourth edition copy “along with numerous pirated editions, generations of enthusiasm for each of Fitzgerald's versions,and the vagaries of editorial taste, have made ‘Fitzgerald's poem the Proteus of modern book production’” (386). Decker maintains that “The Rubaiyat is each one of its texts and all of the texts together”.(220)

As mentioned above, Fitzgerald did not view his translation as literal because he “mashed together” the stanzas, and didn’t recreate the form and ideas of the original work. The meteres are different, but as Reynold Nicholson maintains, he “gives us as near an equivalent as possible in English” which is a stanza of “four iambic lines, of which the third one is generally unrhymed, while the first, second, and fourth rhyme together” (28). According to Nicholson Fitzgerald, “quatrains are not independent units but serve a constructive purpose,” which is different from the Persian rubai where each quatrain is a “solitary” entity that is complete in itself (28).

Being literal in translation is connected to verbal fidelity and keeping the form of the original work which as discussed above, doesn’t happen in Fitzgerald’s Rubaiyat. But Herbert Tucker has a different view in this regard. He maintains that Fitzgerald’s translation is literal in the sense that he takes the literal meaning of the words, and not the figurative and mystical meaning conveyed through the symbolic imagery and figures such as wine, flowers, pottery or women which create together a spiritual meaning for the poems as they belong to the Iranian literary and cultural tradition of wine and mystical nature poetry.

Fitzgerald’s constant editing and his selection of the quatrains, reordering them, and the transformations are seen as auto-ekphrasis according to Tucker. Auto-ekphrasis is defined as “literary works that reflect on their own status as aesthetic objects” in waxekphrasis website. In the preface to the edition of 1868 he states that "many of these quatrains seem unaccountable unless mystically interpreted; but many more as unaccountable unless literally" (35). Tucker maintains that “Fitzgerald's literalist affirmation so often took a feisty form because it was embroiled from the start in a polemic against Omar Khayyam's allegorizers” (70). This, according to Tucker, is the reason for the popularity of his book through its “poetic presentation” that made it (as Decker maintains) "the most popular verse translation into English ever made" (225). Tucker defines Fitzgerald’s translation as “textually materialist” and “signifier focused,” in alignment with what he calls “materialist and hedonist” themes of the poems which he believes is foregrounded in Fitzgerald’s handling of metaphor and mystical and symbolic elements in the poems which he takes very literally.

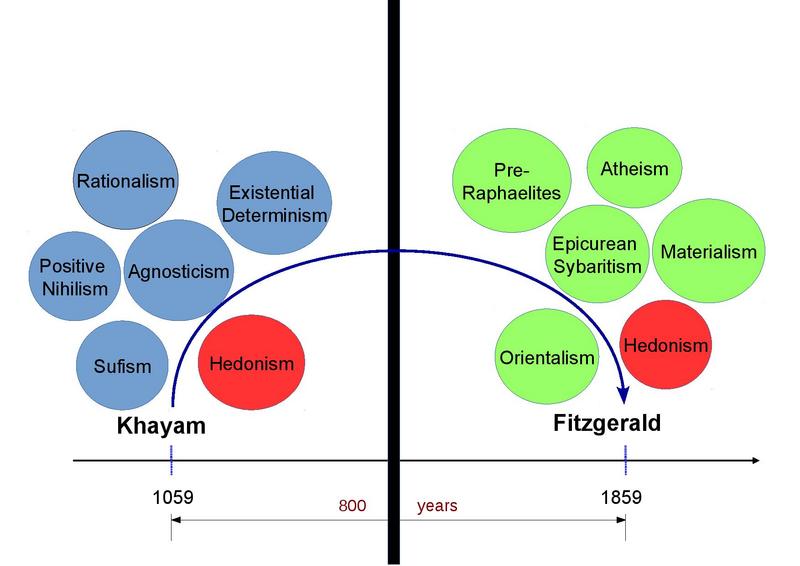

Diagram Showing Differences Between Eastern and Western Reading of Rubaiyat of Omar Khayam according to Mehdi Aminrazavi

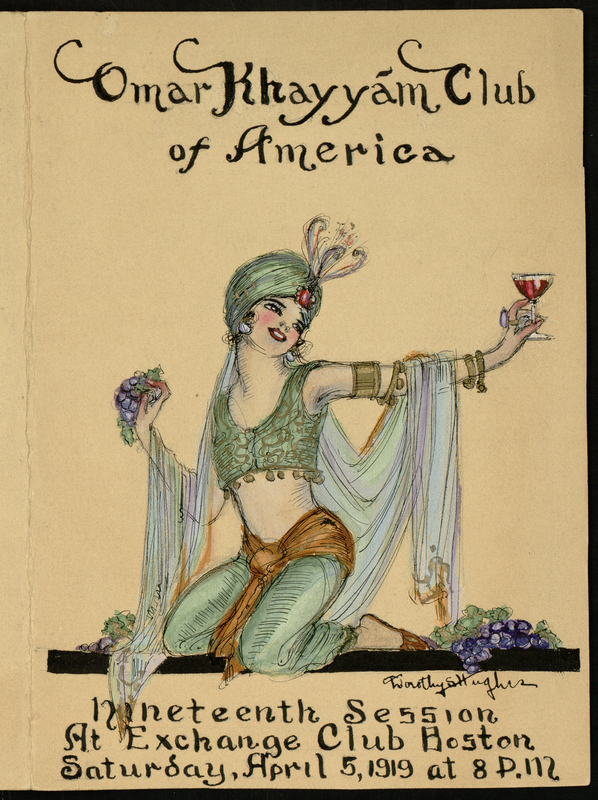

Souvenir menu for the annual dinner of The Omar Khayyam Club of America from 1919. (Image courtesy of the Harry Ransom Center)

Khayam in the West

The multi-faceted Khayam in Fitzgerald’s translation has one face only. Aminrazavi maintains that “while we are indebted to his translation which introduced Khayam to the literary community, he is also responsible for the misconceptions he created precisely due to the selective nature of his translations” (360). He believes that this selection was based upon Fitzgerald's emotional condition and through this translation he tried to “deal with his profound unhappiness” (374). The recurrent theme of sadness in Fitzgerald's Rubaiyat according to Norman Kelvin, “with only drink as consolation” undermines the “role of will” and diminishes “the complexity of meaning” (118).

Aminrazavi’s contention is that “Khayam’s profound existential philosophy became the victim of this stereotypical exotic, esoteric, oriental philosophy”, a romanticization of his views that makes him the “embodiment of the so-called oriental wisdom” (360). This attitude, according to him, could be seen in the description of the first session of Khayam’s club of America by its founder: “from the persian vase in the table’s center with its one rose of Kashmir to the various items of the menu from Chilo to Shirazi Wine and Persian rose leaves, the session was decidedly Omarian” (379).

The historical environment of the late 19th century and early 20th played an important role in creating the Western image of Omar Khayam which, according to Aminrazavi, is an incomplete one. He maintains that:

Khayam’s Western exotic image is not an accurate depiction of this mysterious and misunderstood philosopher, poet and scientist of the 11th century. The first world war in Europe and the Civil War in America had left deep scars on the soul of Western societies, it is not surprising therefore to see that Khayyam’s message concerning suffering and evil resonated deeply with the Western audience. On the other hand, materialism, secularism and spiritual humanism as is evident in the case of the “New England School of Transcendentalism” was on the rise. The puritanical spirit of the founding fathers was slipping away into what the Christian fundamentalists saw as the rise of a new paganism. The exotic East embodied in the very being of Omar Khayam, as represented in his Rubaiyat advocated freethinking, rebellion against religious thought and establishment, spiritualism and living in there here and now. It must have been intriguing to the Victorian audience who saw humanism as the fruit of the renaissance to discover that the wise master from the East also advocated the same. (380)

There are differences between the Eastern and Western reading of the Rubaiyat. The central theme in Khayam according to Aminrazavi is “the notion of impermanence” and life being “fundamentally unjust” (160). In this situation “the wise have no choice but to focus on the here and now.” Doubt, death, existential determinism, skepticism, and the concept of wine are the main themes of his poems which according to Aminrazavi can have very different interpretations: The wine could be “the intoxicating wine," “the wine of love” and “the wine of wisdom” (180). And the theme of the “here and now” could provoke “Buddhist path of moderation,” “epicurean sense of hedonism” or “the Sufi as the child of the moment” (181).

The diagram in this section shows some of the main differences between the Eastern and Western images of Omar Khayam. Both sides have the hedonistic themes in common. However Eastern Khayam is agnostic, rational, puzzled by the mysteries of life and deals with existential concepts while the Western Omar is atheist, sybaritic and epicurean. These dissimilarities, however, are not caused by Fitzgerald’s translation only and as Cutter maintains speak more of the “separate and contradictory cultural and linguistic entities” where the “permeation of barriers” hardly ever happens (32). Despite all the differences between the Eastern and Western image of Khayam, Fitzgerald's translation remains the best translation of Rubaiyat because he "captures the heart and soul" (184) of the poems and transfers it to the reader.

Works Cited

Aminrazavi, Mehdi. The Wine of Wisdom: The Life and Philosophy of Omar Khayam. One World Publications. 2005.

Barrie, J. M. When a man's single : a tale of literary life. Hodder and Stoughton, 1888. (Special Collections: PR4074 W5; 1888)

Barrie, J. M. My lady Nicotine. Hodder and Stoughton, 1890. (Special Collections: PR4074 M9; 1890)

Cutter, Martha J. Lost and Found in Translation: Contemporary Ethnic American Writing and the Politics of Language Diversity. The University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

Decker, Christopher. "Edward Fitzgerald and other men's flowers: allusion in the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayam." Literary Imagination, Vol. 6, no. 2, 2004, pp.213-239.

Fitzgerald, Edward.The Letters of Edward Fitzgerald. Edited by Alfred McKinley Terhune and Annabelle Burdick, 4 vols., no. 3, 1980, pp. 337.

Fitzgerald, Edward. Rubaiyat of Omar Khayam. Hodder & Stoughton, 1909. (Special Collections: PK6513 A1 1909)

Fitzgerald, Edward. Rubaiyat of Omar Khayam. Bernard Quaritch, 1879. (Special Collections: PK6513 A1 1879)

Fitzgerald, Edward. Rubaiyat of Omar Khayam. Collins' Clear Type Press, 1900.(Special Collections: PK6513 A1 1900a)

Fitzgerald, Edward. Rubaiyat of Omar Khayam. T.N. Foulis, 1900. (Special Collections: PK6513 A1 1900)

Fitzgerald, Edward. Rubaiyat of Omar Khayam. John Lane Publisher, 1901. (Special Collections: PK6513 A1 1901)

Fitzgerald, Edward. Rubaiyat of Omar Khayam. Eyre& Spottiswoode, 1910. (Special Collections: PK6513 A1 1910)

Fitzgerald, Edward. Rubaiyat of Omar Khayam. Siegle, Hill & Co., 1911. (Special Collections:PK6513 A1 1911a)

Fitzgerald, Edward. Rubaiyat of Omar Khayam. Siegle, Hill & Co., 1911. (Special Collections:PK6513 A1 1911)

Fitzgerald, Edward. Rubaiyat of Omar Khayam. Routledge, 1912. (Special Collections:PK6513 A1 1912)

Fitzgerald, Edward. Rubaiyat of Omar Khayam. Golden Cockerel, 1938. (Special Collections: PK6513 A1 1938)

Fitzgerald, Edward. Rubaiyat of Omar Khayam. Garden City Doubleday, 1952. (Special Collections: PK6513 A1 1952)

Fitzgerald, Edward. Rubaiyat of Omar Khayam. Penguin, 1972. (Special Collections: PR6013 R35 O6 1972)

Fitzgerald, Edward. Rubaiyat of Omar Khayam. Edited by Christopher Decker. UP of Virginia, 1997.

Fitzgerald, Edward. Rubaiyat of Omar Khayam. Edited by Reynold Alleyne Nicholson. A & C. Black Ltd., 1933.

Hodder and Stoughton Website. "Hodder & Stoughton Company Profile." 11 Dec. 2016, www.hodder.co.uk/Information/About Us.page.

Kelvin, Norman. "Rubaiyat of Omar Khayam, edited by Christopher Decker." Victorian Poetry, Vol. 36, no. 1, Spring 1998, pp.117-122.

Paz, Octavio. The Poet's Other Voice: Conversations on Literary Translation. Edited by Edwin Honig. University of Massachustts, 1985.

Pitman, Emma Raymond. Central Africa, Japan, and Fiji : a story of missionary enterprise, trials and triumphs. Hodder and Stoughton, 1882. ( Special Collections: BV3520 P58)

Tucker, Herbert F. "Metaphor, Translation and Autoekphrasis in Fitzgerald's Rubaiyat." Victorian Poetry. Vol. 46, no. 1, 2008, pp. 69-85.

Wax Ekphrasis Website. "Ekphrasis." 11 Dec. 2016, ww.waxekphrastic.wordpress.com/ekphrasis/

Weinberger, Eliot. Nineteen ways of Looking at Wang Wei: How a Chinese Poem is Translated. Edited by Octavio Paz. Moyer Bell Limited, 1987.

Wormald, Mark. "Rubaiyat of Omar Khayam, edited by Christopher Decker." Review of English Studies, Vol. 49, No. 195 (Aug., 1998), pp. 385-386.

Yeats, W. B. The shadowy waters. Hodder and Stoughton, 1900. (Special Collections: PR5904 S4; 1900)

AK/Fall 2016

Decorations Made by Willy Pogany for Fitzgerald's Rubaiyat Published by Spottswoode, Ballantyne & Co. ( 1932)

Illustration and Decorations Made by Willy Pogany for Fitzgerald's Rubaiyat Published by Spottswoode, Ballantyne & Co. (1932)

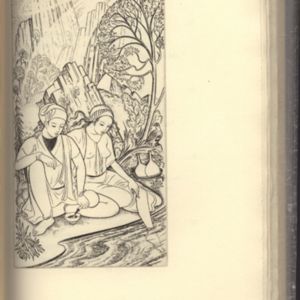

Illustration Made by Abanindo Nath Tagore for Fitzgerald's Rubaiyat Published by Leopold B. Hill (1920)

Illustration made by F. Sangorski and G. Sutcliffe for Fitzgerald's Rubaiyat Published by Siegle,Hill and Co. (1911)

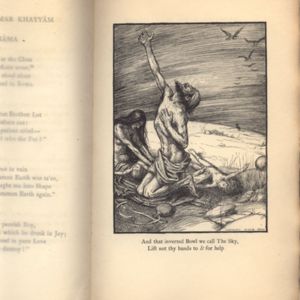

Illustration made by John Buckland Wright for Fitzgerald's Rubaiyat Published by Golden Cockerel Press (1938)

Gallery of Illustrations and Decorated Pages from Different Editions of Fitzgerald's Rubaiyat Available at the University of Victoria Special Collections Showing the Thought-Provoking Differences in the Visual Representations of the Rubaiyat in the Works of Mainly Western Artists