The History of the World (1614)

Portrait minature of Sir Walter Ralegh by Nicholas Hilliard, 1585, National Portrait Gallery, Wikimedia Commons.

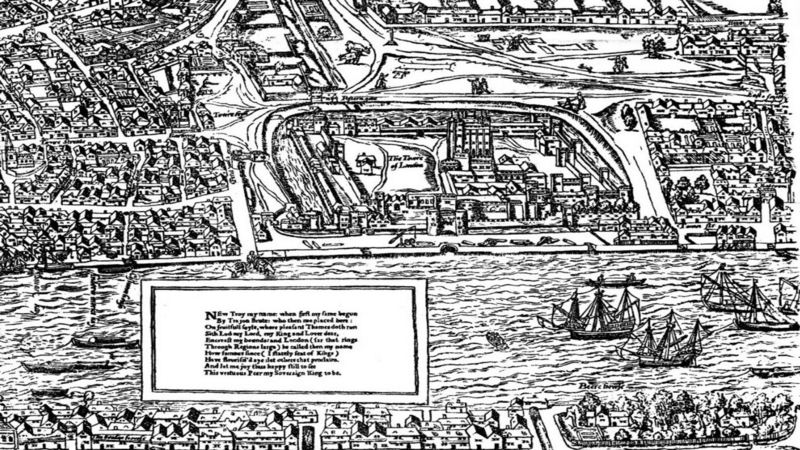

Ralph Agas map depicting the proximity of the Tower of London to the Thames, 1633, Map of Early Modern London.

"To the tune of them that weep": Sir Walter Ralegh's The History of the World, Grief, and Theatricality in Print

I. Intro: Court and Confinement

Crafted in about 1585, Nicholas Hilliard’s miniature of Sir Walter Ralegh depicts him as the ideal Elizabethan. With a ruff that encompasses slightly over half of the frame and vibrant colours that seem to highlight the courtier’s status as one of Elizabeth’s favourites, it is easy to remember Sir Walter Ralegh through a mythic lens. He was a revered poet, one of the most renowned explorers of all time, a soldier, a spy, and some go so far as to speculate that he was a lover of the Queen herself. Yet for the purposes of discussing his 1614 The History of the World, it is necessary to shift focus to the Jacobean Ralegh, who had fallen out of the favour of the court. In 1603, the death of Queen Elizabeth I marked the close of the Elizabethan era, and with it, the end of Ralegh’s royal approval. Later in that same year, Ralegh’s fourteen-year confinement in the Tower of London began based on his alleged involvement with the Main Plot, a "conspiracy against King James I’s life" (Partides 3).

Though he was confined, he was not at all isolated in the Tower. In fact, visiting Ralegh seems to have been something of a fashionable activity for Londoners. From his position in the Tower, the incarcerated explorer could see ships enter and depart the Thames, recalling his past expeditions. His time spent in incarceration would also bring him into direct contact with Ben Jonson, a rival of Shakespeare and perhaps the second most widely-read playwright of the early modern era. As well, he would have been acquainted with Prince Henry Frederick, the heir-apparent to James I who, had he survived into adulthood, would have been England’s King Henry IX. Throughout his time in the Tower, Ralegh was known to write letters of advice to the future monarch. At one point, Henry supposedly said, “‘Only my father would cage such a bird’” (Jones 275). Ralegh and Henry’s relationship has amassed a great deal of scholarly attention over the last four decades. Whether Ralegh wrote his History of the World to advise the Prince as a political action is a question that evades a simple answer. It is also possible that Ralegh appealed to the prince as a plea for mercy or simply to avoid censorship of his potentially scandalous work.

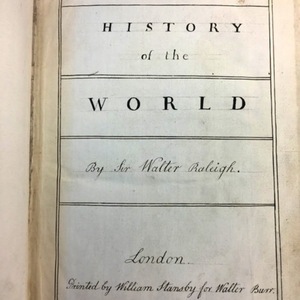

We know that The History of the World was entered into the stationer’s register in 1611 “quite possibly with Prince Henry’s encouragement” (Popper 16), roughly eight years into Ralegh’s fourteen years in the Tower. The first edition of The History of the World was published namelessly in 1614, two years after Prince Henry’s death of typhoid fever. After its publication, the book was quickly suppressed by James on the grounds that it was “too sawcie in censuring princes” (qtd. in Popper 18). Ralegh would eventually obtain a pardon and be released from the Tower in 1617 to find the lost city of El Dorado for King James, during which time a new edition of History would be published, this time bearing his name and sold for royal profit (Tennenhouse 256). The voyage to discover El Dorado would prove disastrous for Ralegh. Not only would it lead to an attack on the Spanish that would result in the death of his son, but it would also lead directly to his execution in 1618.

II. The Reader is Dead

The majority of scholarly attention to The History of the World is focused on its role in Renaissance historiographical culture, and rightfully so. Simply focusing on History as a physical object, the book emblematizes Prince Henry’s death as major fracturing point in the literary culture of the early seventeenth century. Moreover, Ralegh’s frequent use of the language of the stage (discussed in section IV) indicates his awareness of his readers as theatre-goers. To complicate Barthes’s “The Death of the Author”, the lone volume of The History of the World speaks to the actual mortality of the author that is highly connected to the death of the reader. The frontispiece, the preface, the printer’s mark, and the final chapter all indicate that The History of the World is an inherently social text that is part of a literary culture that held Prince Henry as a nationalistic, militaristic, Protestant icon. Paradoxically, Ralegh’s “confinement kept him near the centre of Jacobean affairs” (Popper 16). As such, the text is also a way for Ralegh to communicate with his readership and critique a monarchy from within the Tower. Yet the death of the reader embeds a tragic weight into History itself, forcing it to exist as an item “now left to the world without a Maister” (E5R) as Ralegh was left imprisoned without his best hope for freedom.

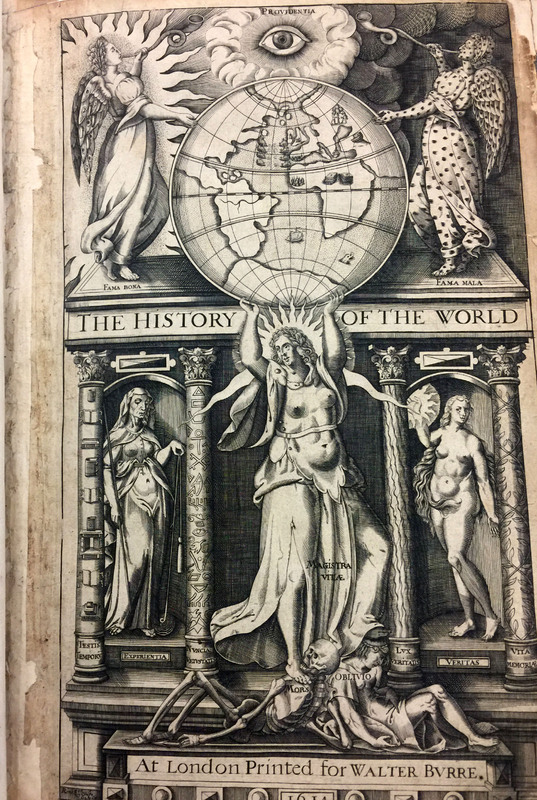

Frontispice from The History of the World by Renold Elstracke, 1614, University of Victoria Special Collections.

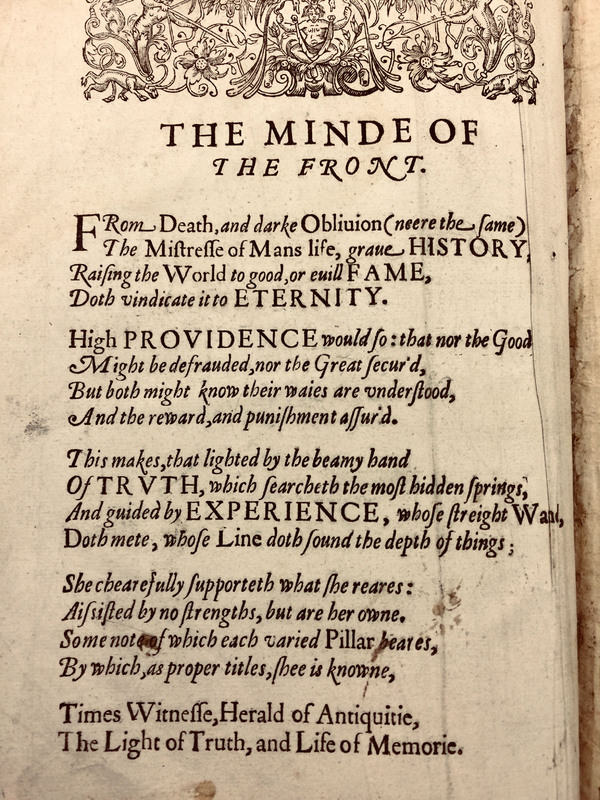

Ben Jonson's Explanatory poem to The History of the World, 1614, University of Victoria Special Collections.

III. Magistra Vitæ: On the Fontispiece and Jonson's Poem

At the very forefront of the book, Ben Jonson’s introductory poem is juxtaposed with Renold Elstracke’s ornate woodcut frontispiece, which is “‘the most elaborate of its kind known in English bibliography’” (William Stebbing qtd. in Partides xv). The frontispiece effectively functions as the point of entry before Ralegh’s providential interpretation of history. It depicts the “Ciceronian maxim that history is ‘the teacher of life, the witness of times, the herald of antiquity, the light of truth, and the life of memory’” (Popper 23). If nothing else, the frontispiece speaks to the text as something that is profoundly important, closely connected to the early modern humanist culture that revered the Greco-Roman past. The frontispiece also depicts ships crossing the Atlantic directly under the eye of providence, indicating Ralegh’s own achievements as an explorer. The presence of Ralegh’s nautical paths hints that readers likely would have had some familiarity with Ralegh’s celebrity. The fact that Elstracke’s woodcut is so detailed, pronounced, and ornate perhaps speaks to the tastes of the readers. The folio-sized book itself becomes a physical symbol of learnedness. That said, it likely would have not have been inexpensive. It is, after all, a book fit for a prince.

The placement of Jonson’s poem with Elstrack’s woodcut establishes the text as an inherently social space. Just as Walter Ralegh’s cell was confining yet social, the book itself is a confined space that holds the work of Ralegh, Jonson, Elctracke, and William Stansby, all too be sold by Walter Burre. The method of textual production would have been far from an isolating activity as Ralegh himself had designed the frontispiece, which had to be designed by Elstracke and poetically introduced by Jonson (Popper 23). It would have been necessary that they all shared the same creative vision to produce the textual output. One of the things that this collaborative space emphasizes, though, is a heightened awareness of death and mortality.

In terms of textual memorialization, recent scholarship by Jonathan Lamb argues that the very design Ben Jonson’s 1616 Folio is similar to the mourning books published for Prince Henry— more specifically, that “Jonson’s Workes uncannily recapitulates the poetics and typography of grief evident in the public mourning of Henry’s loss” (65). To extend his thesis to Ralegh’s History, the 1614 edition ties the act of mourning to the poetry printed in its textual space. The presence of Jonson’s poem is also indicative of an overlap between early modern England’s theatrical and literary cultures. Jonson’s poem in The History of the World indicates the extent to which Prince Henry’s death impacted print culture. The work was printed by William Stansby, who also printed Jonson’s Workes two years after The History of the World was first published.

In the years of 1612-13, Jonson was abroad. This meant that he would receive news of Prince Henry’s death after the nation’s initial shock had subsided. During this time, though, he “was serving as the governor to the youthful Walter ‘Wat’ Ralegh” (Lamb 64). Jonson's mentorship of Sir Walter Ralegh's son is perhaps indicative of a certain degree of closeness between the two figures of early modern celebrity. Between using the same printer for their works and quite probably convening regularly, it is no wonder that Jonson, whose work is so heavily involved in the mourning culture surrounding Prince Henry's death, seems to invoke those same elements of memorialization that are apparent in his introductory poem.

Jonson's interpretation of Elstracke's frontispiece also brings to the book a certain level of acclaim, since after all, he was an poet and playwright of great renown. Not unlike Ralegh, Jonson had a status of literary celebrity, which make it a curious fact that the first editions of History appeared without Ralegh or Jonson’s names in print. There likely would have been no doubt regarding who wrote the books, even in the absence of their names. The frontispiece's depiction of ships bear quite a clear association to Ralegh, whose presence is clarified as he makes several references in his preface to his status as a known figure who specifically fell from the grace of Queen Elizabeth:

"For my ſelfe, if I haue in any thing ſerued my Country, and priſed it before my priuate: the general acceptation can yeeld me no other profit at this time than doth a faire ſunſshine day to a Sea-man after ſhipwrack & the contrary no other harme than an outragious tempeſst after the Port attained. I know that I loſt the loue of many, for my fidelity towards Her, whom I muſt ſtill honor in the duſt..." (A1R).

As demonstrated through the juxtaposition of nautical imagery with mourning Queen Elizabeth I's death, there is little doubt that readers would have been aware of the man behind the book. The idea of "ſtill honor[ing] in the duſst," moreover, speaks directly to the obsession with grief that prevades History.

To expand upon Lamb’s idea that “to read Jonson’s Folio is to become a mourner” (66), I argue that reading Jonson’s explanatory frontispiece to The History of the World asks us to assume that same status.

“From Death and darke Obliuion (near the ſame)

The Mistreſſe of Mans life, graue HISTORY,

Raising the World to good, or euill FAME,

Doth uindicate it to ETERNITY” (ln. 1-4)

reads the first stanza of Jonson’s introductory poem. Bearing in mind that the poem would have been probably been written in about 1614 since it explains the frontispiece that we know to be published in that year, it is fitting that it is attuned to the overtones of death as it would have been close to the publication of Jonson's mourning books (see Lamb's "Ben Jonson's Dead Body" for a thourough discussion of Jonson's mourning books). The concluding lines of the poem allow it to take on an extra significance when considering Jonson’s involvement in textual mourning:

“Times witneſſe, Heralde of Antiquitie,

The Light of Truth, and Life of Memorie” (ln. 17-8).

The poetry is quintessentially Jonsonian, harkening back to antiquity and prizing ideas of truth and memory. Yet what is evident from the frontispiece and from the explanatory poem is the idea that the text is a way to transcend the typical human lifespan, to lift the world from “Death and darke Obliuion” through studying the past. Jonson, like Ralegh, is a figure who was obviously concerned with memory. In the absence of its ability to edify Prince Henry, the text also appealed to readers concerned with their own demise. The ornate frontispiece speaks literal volumes of the humanist idea that a text could allow the author to take on a life after death. Yet still, it cannot be avoided that the death of the heir-apparent some two years prior establishes the overtone of mourning for The History of the World.

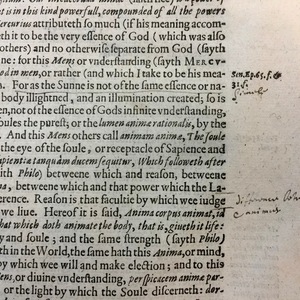

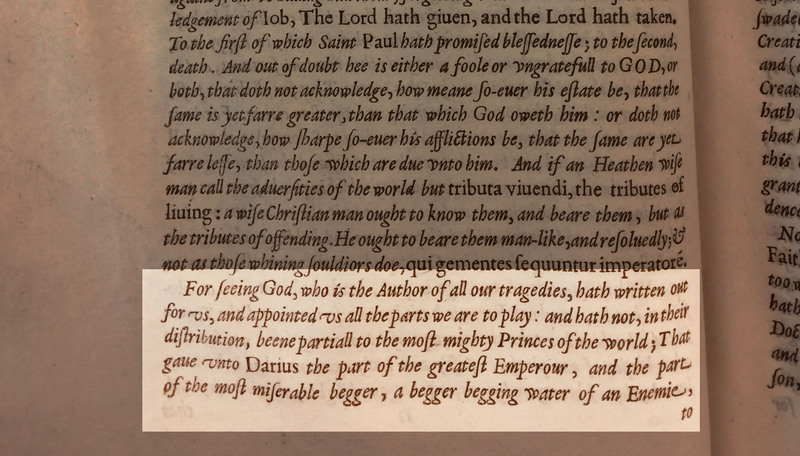

Excerpt from Preface, D1v, University of Victoria Special Collections.

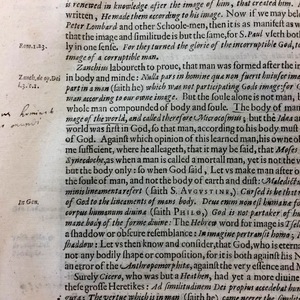

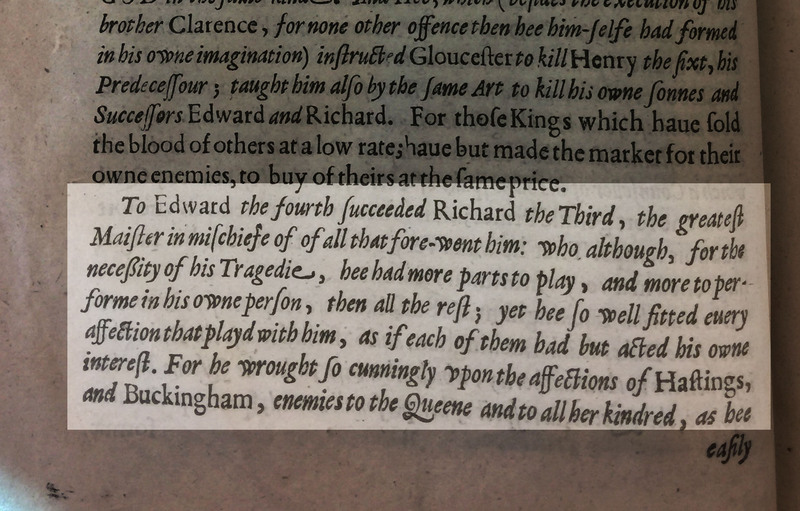

Excerpt from Preface A3R, University of Victoria, Special Collections.

IV. History as a Stage

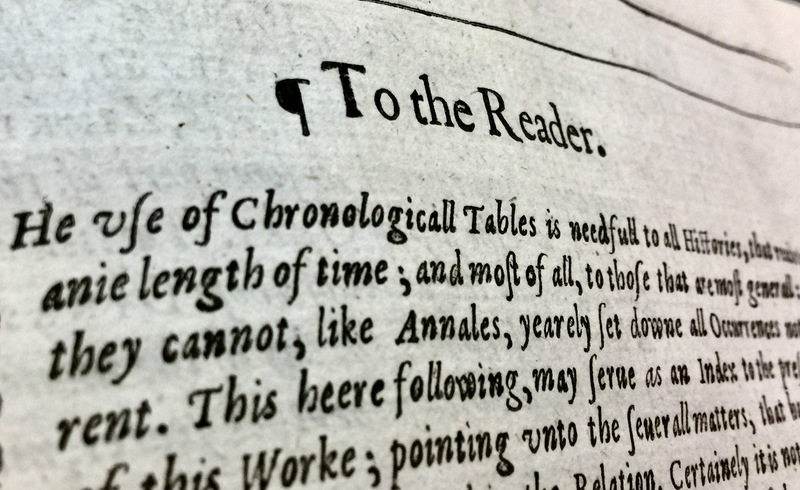

Based on the fact that Jonson’s are the first words printed in the book, History cannot resist immediate theatrical association. Andrew Gurr argues that “we can envision Shakespeare’s audiences as being composed not only of a ‘great variety of playgoers,’ but also a great variety of readers” (qtd. in Clegg 11). Since attending the theatre is hearing a written script performed, playgoing is closely tied to the act of reading itself. While readers certainly would have been in attendance at the theatres, inversely, theatregoers would have also been present at the book stalls. Ralegh’s work, in effect, seems to have been crafted with an acute awareness of his reading audience as playgoers.

In his introduction, Ralegh uses theatrical language liberally with relevance to history, stating that “For ſeeing God, who is the Author of all our tragedies, hath written out for vs, and appointed vs all the parts we are to play: and hath not, in their distribution, been partiall to the most mighty Princes of the world” (D1R). Ralegh asking his readers to imagine life as a tragedy allows him to expand his providential view of history while using theatrical language to call to mind that theatre, like history, functions as an educational tool to understand the moment at hand. More specifically, Ralegh expands the imagined theatrical space so that God is the playwright and all of mankind are actors in their hour upon the stage. It is difficult to overlook his references to 'Princes' as a relatively limpid reference to Prince Henry.

Ralegh indicates the overlap between theatrical culture and historiography in writing about Richard III, stating that he was “the great Maister in mischief of all that fore-went him: who although, for the necessity of his Tragedie, hee had more parts to play, and more to performe in his own person, than all the rest” (54). As Ralegh is discussing the historical monarch, it almost seems as though he is discussing Shakespeare’s play, staged in 1592. While I do not wish to be as prescriptive as to state that Raleigh would have seen the play in Queen Elizabeth's court, what I do want to note is the fact that, at the very least, Ralegh is aware of Richard III's status in the mind of his readers as a theatrical, rather than a historical figure. History plays overlap with historical culture. The stage is a historical space just as Ralegh's historiographical text is a theatrical space.

On a broader level, the theatrical undercurrent of Ralegh’s words exhibits a knowledge of theatrical culture and uses it as a point to establish common ground with his readership. With such an introduction that almost reads as the prologue to a play and a frontispiece that almost resembles a stage, it is fitting that Ben Jonson's words should be the first that readers see.

In terms of Ralegh’s awareness of the interplay between his text and the stage, it was not uncommon to see a portrayal of Ralegh or a reference to him in the Jacobean theater. This indicates not only his celebrity, but speaks to the presence of a theatrical culture that was keen on staging Ralegh’s likeness. In Thomas Middleton and William Rowley’s An/The Old Law, likely performed around 1618, the year of Ralegh’s death, Creon makes a possible reference to Ralegh’s imprisonment:

“He that has been a soldier all this days

And stood in personal opposition

‘Gaintst darts and arrows, the extreme heat

And pinching cold, has treacherously at home

In his securèd quiet by a villain’s hand" (1.1.237-41).

While it is not abolutely certain that Creon's reference directly evokes Ralegh, no doubt audiences would have been familiar with the image of the former soldier "In his securéd quiet by a villain's hand," the memory of his execution fresh in their minds or looming in the near future. It is also not uncommon for scholars to argue that Don Adriane de Armado in Shakespeare’s Love’s Labour’s Lost bears certain characteristics of Sir Walter Ralegh and those more prescriptive have speculated that Hamlet’s “To be or not to be” speech references Ralegh’s attempted suicide in the tower that was conveyed in a letter by Robert Cecil in 1603 (Pemberton 153). Those who entertain the possibility that Shakespeare did not write the plays attributed to him have also proposed Sir Walter Ralegh as a possible author.

William Stansby's Printer's Mark in 1614 History of the World, University of Victoria Special Collections.

A Sermon preached from St. Paul's Cross in 1614, John Gipkyn, Society of Antiquaries, London. Wikimedia Commons.

This is St. Paul's depicted the year that History came into publication and was sold there.

V. "At the ſigne of the Crane": St. Paul's Cathedral

In the seventeenth century, St. Paul’s Cathedral was essentially the social hub of London. More than that, it was a highly theatrical space, at one time housing its own playhouse where The Children of St. Paul’s preformed their repertoire of city-comedies. Paul’s Cross was also home to open-air preaching, which is a theatrical event in and of itself. As a place with a thriving textual and mercantile culture, Reavley Gair states that it was “the Elizabethan equivalent of an indoor shopping mall” (31). Thomas Dekker gives a sort of cast list for St. Paul’s in his Paul’s Steeples Complaint:

“You could see: The Knight, the Gull, the Gallant, the upstart, the Gentleman, the Clowne, the Captaine, the Appel-squire, the Lawyer, the Usurer, the Cittizen, the Bankerout, the Scholler, the Begger, the Doctor, the Ideot, the Ruffian, the Cheater, the Puritan, the Cut-throat, the Hye-men, the Low-men, the True-man and the Thiefe: of all trades & professions some, of all Countreyes some […]” (qtd. in Gair 33).

A variety of "characters" from different backgrounds and social statuses would have been present at any given time, characterizing the place that History would have been sold. St. Paul’s is effectively a space of overlap between theatrical, mercantile, ecclesiastical, and literary culture. The fact that History was sold there speaks to reading as an often communal activity, further allowing Raleigh to communicate with the masses from within the Tower itself.

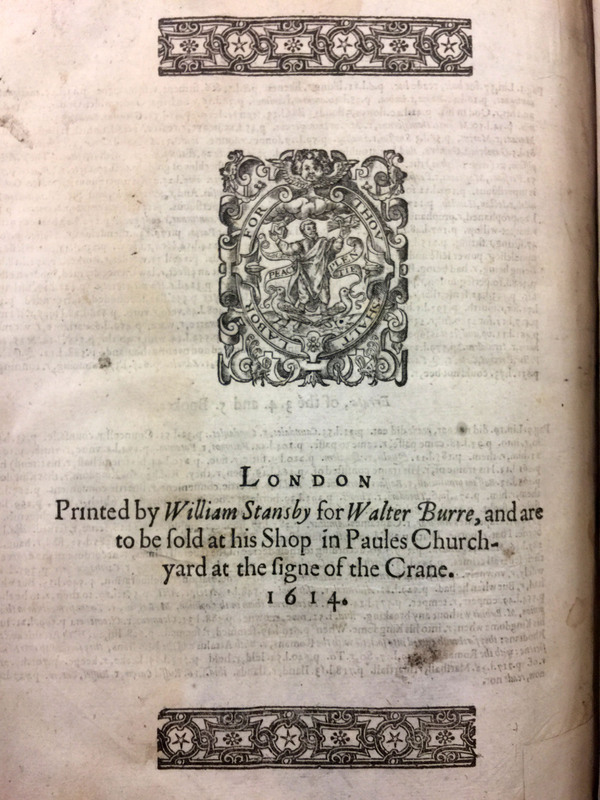

The bookplate on the final page of History states that the book reads, ‘Printed by William Stansby for Walter Burre, and are to be ſold at his Shop in Paules Church-yard at the ſigne of the Crane- 1614.” As stated previously, William Stansby was a particularly important figure in the print culture of Jacobean London because he “ran one of the largest printing business is London, producing small quantities of high-quality texts by famous authors such as Donne, Ralegh, and Jonson, whose Workes he printed in 1616” (Quinn). There seems to have been a high status associated with Stansby’s works. The 1616 Folio of Jonson’s Workes is one of the most famous in early modern print culture because it was published during the playwright’s lifetime and he was closely involved in the printing process. Though Ralegh would have been kept from the same proximity to the printing process simply on the basis of his incarceration, the sheer magnitude of The History of the World is a literary achievement. Not only its number of pages, but the nature of the textual fixtures like maps and graphs would have demanded a skilled, advanced printing operation. Folio-size texts also indicated a certain esteem. As Stephen B. Dobranski notes, “A brief survey of William Stansby’s folio catalogue reveals mostly historical and philosophical texts. Before printing and publishing Jonson’s volume, Stansby had worked on Richard Hooker’s Of the Lawes of Ecclesiasticall Politie, Walter Ralegh’s The History of the World, William Camden’s first volume of his Annals, and William Martyn’s The History, and Lives, or Twentie Kings of Engliand. These books, with their ample margins and generous layout, were both erudite and dignified— just what a poet/ dramatist like Jonson would have wanted to evoke in trying to establish his laureate status” (104). As such, Stansby’s work seems to cater to the more educated, gentlemanly classes. Walter Ralegh may have fallen out of Royal favour, but he was nevertheless a key figure in London’s print culture. Cross-referencing Stansby with the English Short Titles Catalogue reveals that he was behind new fewer than 528 printed works in his time, ranging from pamphlets to plays to poems to works by early modern antiquarians. It is appropriate that The History of the World draws upon the theatrical, the poetic, and of course, the historical. Presumably, the copies of The History of the World sold quite well as several editions followed the first.

The History of the World’s association with bookseller Walter Burre is slightly more complicated as there is simply less information available with regard to booksellers. Robin Myers and Michael Harris note that around Saint Paul’s there was “a dense concentration of booksellers living and working in premises of varying size, though all on a small scale, and interspersed with the shops of other small-scale artisans, together with a few larger houses of wealthier professionals” (51). Unlike the massive number of printed texts attributed to the press of William Stansby, the ESTC only reveals about 50 books associated with Walter Burre, several of which are printed sermons and Ben Jonson’s plays. Appropriately for a discussion on Sir Walter Ralegh, the first entry in 1615 is by C.T., entitled, “An aduice on hovv to plant tobacco in England:.”

St. Paul’s was the key to London’s social scene. As such, it is fitting that a work that gained enough notoriety as to attract the attention of King James himself would be published and sold there. The Bookstalls were effectively a melding of classes, a place where theatrical, news, poetics, and if History is any indication, humanist culture all met. Ralegh’s text is heavily social, as displayed by how many hands it passed through by the time it reached the hands of the reader. With an association with Stansby and Jonson, the text would have been a signifier of class if illustrated by nothing other than its folio size. The remarkable preservation of it and the apparent lack of readership, though, shows that History was likely something of an ornament, something more decorative than useful.

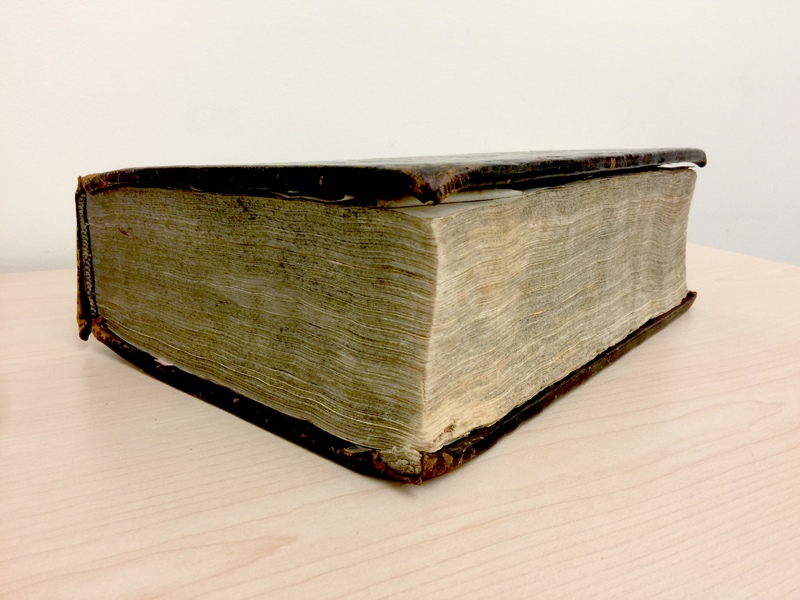

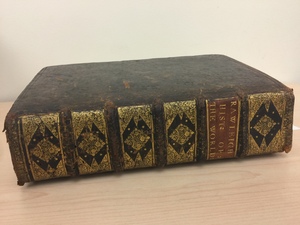

Binding of Sir Walter Ralegh's History of the World, 1614, University of Victoria, Special Collections

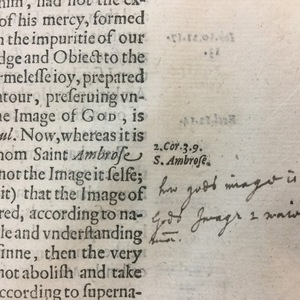

VI. Readership and Booktraces

In Nicholas Popper’s History of the World and the Historical Culture of the Late Renaissance, he remarks that most surviving copies “contain no markings or only a few inscrutable scribbles and jotting of the owner’s name, sums, or geometric designs, and many of their pages give off a dank, malevolent odor borne of centuries of moisture and neglect” (255). The University of Victoria’s 1614 copy is no exception to Popper’s observation. There are few book traces between the covers of History. The only information left by four centuries of readership (or lack thereof) is that the book was at one point sold for £350, that someone had written their name above the preface in a show of ownership, and that someone had used the blank front pages to practice penmanship. Since none of the books in the early modern era would have been sold bound, the binding of the book hints at a value ascribed to it some time after its publication. Comparisons to bindings in the Folger Shakespeare Library's LUNA database seem to hint that what is present is a relatively ornate mid-eighteenth century binding, if not later. Popper further presents the idea that “[s]ome owners of History viewed the book primarily as a physical object associated with Ralegh” (256). The importance of the History is strictly based on its association with Ralegh. Its marked lack of readership, though, proves that the memory of the man is more prized than the context of his massive work.

In the 1617 edition of The History of the World, a copy of which is also in UVic’s special collections, the marginalia is even more scarce and the pages exhibit even less wear. The frontispiece has been torn out of this edition, though Jonson’s poem has been reinforced by a page that has been written by hand and attempts to replecate the original frontispiece. The fact that Elstracke’s frontispiece has been removed but great care has been made to obscure the extraction indicates that it was likely sold separately from the book. Again, this hints toward the value of the book as a physical object associated with Sir Walter Ralegh, not something that was particularly revered for the information that it holds.

Both the 1616 and 1614 copies of The History of the World are remarkably preserved precisely because they appear to have been so scarcely read. The pages are remarkably sturdy. They are crisp and their ink is still clear. In the 1614 edition, all marginalia stops about 38 pages into the book. What is present merely exhibits some knowledge of Latin as indicated by the phrase “corpus hominis” (the human body) and some awareness of rhetorical features like ‘simile.’ There are, however, some marginal notes in what appears to be an eighteenth-century hand in which the word "image" is legible. It is possible that whoever owned the book was interested in its connection to Protestantism and idolatry. Whomever the diligent note-taker was, though, did not manage to sustain their dedication past Genesis.

It is difficult to deduce any clear thesis from the present marginal notes. What is most profound is the lack of evidence of readership. Many of the books in the University of Victoria's Special Collections are archives in and of themselves. In a text that appears to have been so revered, it exhibits such little use. Its value exists strictly from its association with its author. While it never reached the hands of Prince Henry, it fell into the possession of many readers who left Ralegh’s laborious work symbolically untouched.

The marginialia that is present in the pages of History indicates general textual observations and displays evidence of ownership; however, it is scarce and only visible in the first few sections of the book. The marginalia provides evidence about previous ownership and one reader's interest in rhetorical devices and biblical ideas.

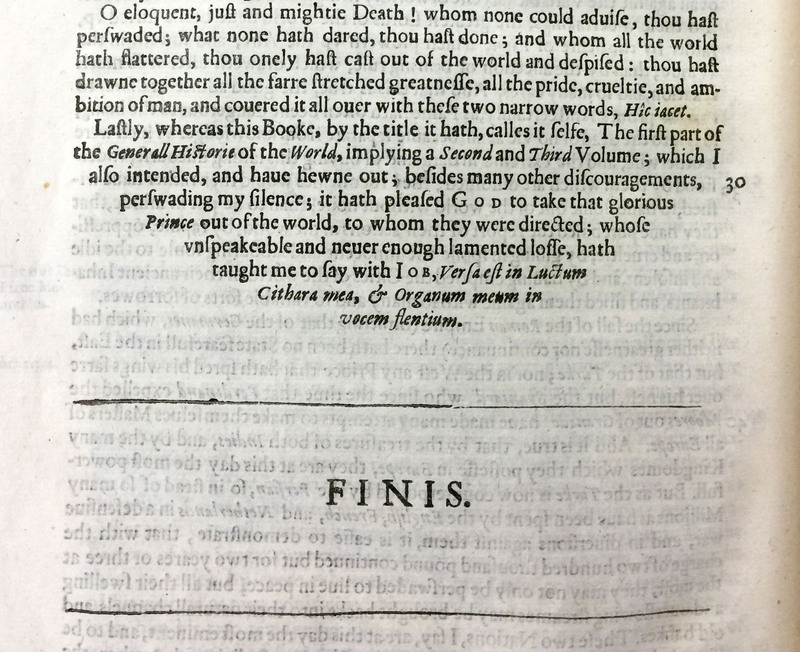

Final page of Sir Walter Ralegh's History of the world (6.S.12), 1614, University of Victoria Special Collections.

"To the Reader" heading of Sir Walter Ralegh's The History of the World, 1614, University of Victoria Special Collections.

VII. Hīc Iacet (Here he Lies)

On the note of Prince Henry’s death, it is fitting to end alongside Ralegh, who in his conclusion notes that he has dashed plans for the future texts:

“whereas this Booke, by the title it hath, calles it ſelfe, The Generall Historie of the World, implying a Second and Third Volume; which I alſo intended, and haue hewne out; beſides many other diſcouragements, perſwading my ſilence; it hath pleaſed G O D to take that glorious Prince out of the world, to whom they were directed; whoſe vnſpeakeable and neuer enough lamented loſſe, hath taught me to ſay with I O B, Versa est in Luctum Cithara mea, & Organum meum in vocem flentium” (6.S.12).

The final Latin words translate to “My harp also is tuned to mourning, and my organ to the voice of them that weep.” It seems that in this massive textual endeavour, left to the world “without a maister” (E5R) follwing Prince Henry’s death, Ralegh has learned the lessons of mourning. It is fitting that he should cast himself as a character not unlike Job, who himself suffered under Ralegh's providential history. Yet is Ralegh mourning for his own life or for Henry's? In the textual space of the book, the two are closely connected. We would supposedly have more history, more words written, if Henry had lived. Yet the text ends in about 162 BC, leaving a massive section of time only expanded upon in the preface.

Ultimately The lack of readership, the final meditation on death, and the last words allow Ralegh to effectively conclude his historical narrative with a note of mourning:

“O eloquent, juſt and mightie Death! Whom none could aduiſe, thou haſt perſwaded; what none hath dared, thou haſt done; and whom all the world hath flattered, thou onely haſt caſt out of the world and deſpiſed: thou haſt drawn together all of the farre ſtretched greatneſſe, all the pride, crueltie, and amtition of man, and couered it all ouer with theſe two narrow words, Hīc Iacet [here he lies]” (6.S.12).

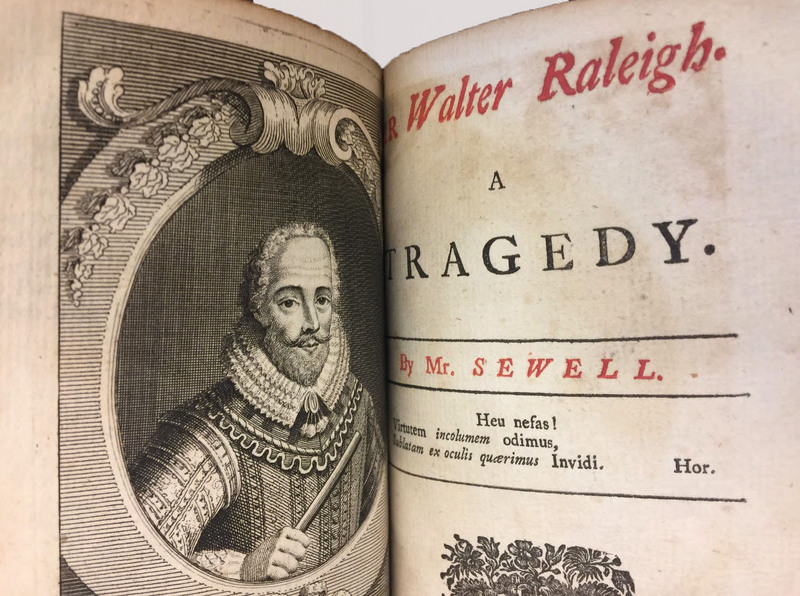

George Sewell's Sir Walter Raleigh: A Tragedy, 1619, University of Victoria Special Collections.

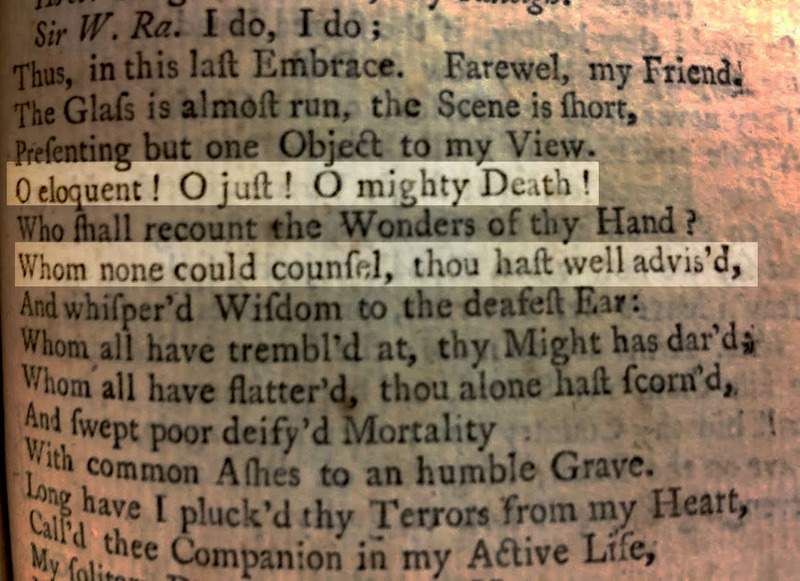

Final speech of George Sewell's Sir Walter Ralegh: A Tragedy, 1719, University of Victoria Special Collections.

VIII. A Theatrical Afterlife

When discussing Sir Walter Ralegh biographically, it is difficult to overlook his presence as a tragic figure. As a courtier, a soldier, a poet, a spy, a prisoner, and a historiographer, his 66 years were certainly riddled with revered achievements. Yet his final years were a tragedy of almost theatrical proportions. Needless to say that the stage-portrayals of Ralegh do not end with his death. As a clear indication of this, UVic’s Special Collections contains a 1719 copy of Dr. George Sewell’s play entitled Sir Walter Raleigh: A Tragedy. In its final moments, Sewell’s Ralegh echoes the final lines from The History of the World:

“O eloquent! O juſt! O mighty Death!

Who ſhall recount the Wonders of thy Hand?

Whom none could counſel, thou haſt well advis’d

And whiſpered Wiſdom to the deafeſt Ear” (z3).

Sewell’s play depicts the heavily theatrical lens through which Sir Walter Ralegh is remembered. The weighty, largely unread copies of The History of the World tell a story beyond simply the encyclopedic recounting of history from Genesis to a few hundred-and-some-odd years before Christ. The story of the book itself is one that takes on a new literary significance when we account for the voice of the author and the loss of its Prince. It is not any of Ralegh's poems, not his famous letter to his wife, not even his Discovery of New Guinea that he quotes, but the final lines of The History of the World. The History of the World itself, then, becomes part of the history of the world with the passing centuries. If we can bear the endeavour, then we, as readers, are not unlike "monarchs to behold the swelling scene" (Shakespeare 1.1.4) in cracking its cover.

See Also in Special Collections:

Barrow, John. A collection of authentic, useful, and entertaining voyages and discoveries. 1765.

Birch, Thomas. The works of Sir Walter Ralegh, kt. 1751

Drake, Samuel G. A brief memoir of Sir Walter Raleigh, 1862.

The last fight of the Revenge... Related by Sir Walter Ralegh. 1595.

Lorimer, Joyce. Sir Walter Ralegh's Discoverie of Guiana. 1879?.

See Also in Moveable Type:

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland. The Death of the Author. The Critical Tradition, ed. David H. Richter, Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2007, pp. 874-8.

Clegg, Cyndia Susan. Early Modern Books and Audience Interpretation. Cambridge UP, 2017.

Dobranski, Stephen B. Readers and Authorship in Early Modern England. Cambridge UP, 2005.

Jones, Nigel. Tower: An Epic History of the Tower of London. St. Martin’s Griffin, 2013.

Gair, Reavley. The Children of Paul’s: the story of a theatre company, 1553-1608. Cambridge UP, 1982. Print.

Lamb, Johnathan P. "Ben Jonson’s Dead Body: Henry, Prince of Wales, and the 1616 Folio." Huntington Library Quarterly, vol. 79 no. 1, 2016, pp. 63-92. Project MUSE.

Middleton, Thomas and William Rowley. An/The Old Law. Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works, ed. Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino. Oxford UP, pp. 1391-1396, 2007.

Myers, Robin and Michael Harris. A Genius For Letters: Booksellers and Bookselling from the 16th to the 20th Century, St. Paul’s Bibliographies, 1995.

Partides, C.A. “Introduction.” The History of the World, Sir Walter Ralegh, ed. C.A. Partides, Macmillan, 1971.

Pemberton, Henry. Shakespeare and Sir Walter Ralegh. Haskell House, 1971.

Popper, Nicholas. Walter Ralegh’s History of the World and the Historical Culture of the Late Renaissance. U of Chicago P, 2012.

Quinn, Mary Katherine. "Stansby, William." The Oxford Companion to the Book. Oxford University Press, 2010. Oxford Reference 2010.

Sewell, Dr. George. Sir Walter Raleigh: A Tragedy. J.P. and J.W., London, 1739.

Shakespeare, William. Henry V, ed. T.W. Craik, Arden, 1998.

Sir Walter Raleigh. The History of the World. William Stansby, London, 1614.

Sir Walter Raleigh. The History of the World. William Stansby, London, 1617?.

Tennenhouse, Leonard. “Sir Walter Ralegh and the Literature of Clientage. Patronage in the Renaissance. Ed. Guy Fitch Lytle and Stephen Orgel. Princeton UP, 1981, p.235-58.

Works Consulted (see Also)

Beer, Anna R., ""Left to the world without a Maister”: Sir Walter Ralegh’s “The History of the world’ as a Public Text.” Studies in Philology, vol. 91, no. 4, p. 432.

Gurr, Andrew, The Shakespearean Stage 1574-1642. Cambridge UP, 2009.

Hinks, John and Victoria Gardner. The Book Trade and Early Modern England: Practices, Perceptions, Connections. Oak Knoll Press, 2014.

Marshall, Tristan. “’That’s the Misery of Peace’: Representations of Militarism in the Jacobean Public Theatre, 1608-1614.” The Seventeenth Century, vol. 13, no. 1., pp.1-21, Taylor and Francis Online, 2013.

Rutter, Tom. Shakespeare and the Admiral’s Men. Cambridge U P, 2017.*

Between 1603-1612, The admiral’s men were known as “Prince Henry’s Men.”

Smuts, Malcom. “1. Court-Centered Politics and the Uses of Roman Historians, c. 1590-1630.” Culture and Politics in Early Stuart England, Ed. Kevin Sharpe and Peter Lake, Stanford UP, 1993.

Straznicky, Marta. The Book of the Play: Playwrights, Stationers, and Readers in Early Modern England. U of Massachusetts Press, 2006.

Willks, Timothy. Prince Henry Revived. Paul Holberton Publishing, 2007.

CT/Fall 2017