The Strand Magazine (1891-1950)

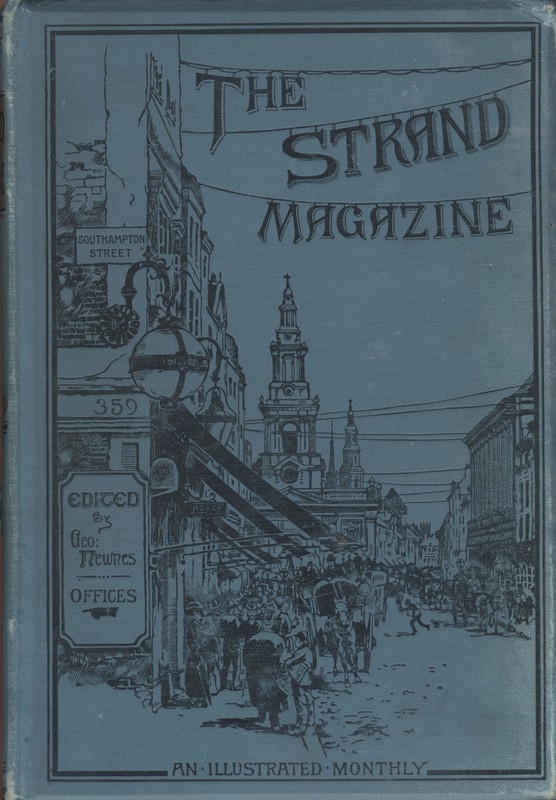

Figure 1 – Front cover by George Charles Haité of The Strand Magazine, volume one (1891).

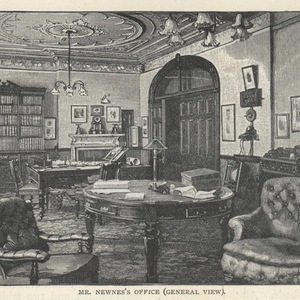

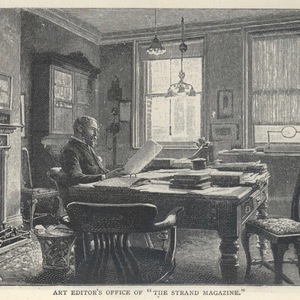

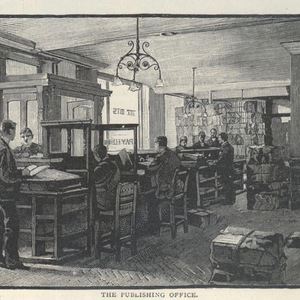

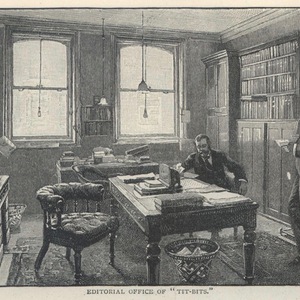

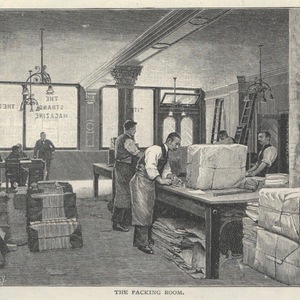

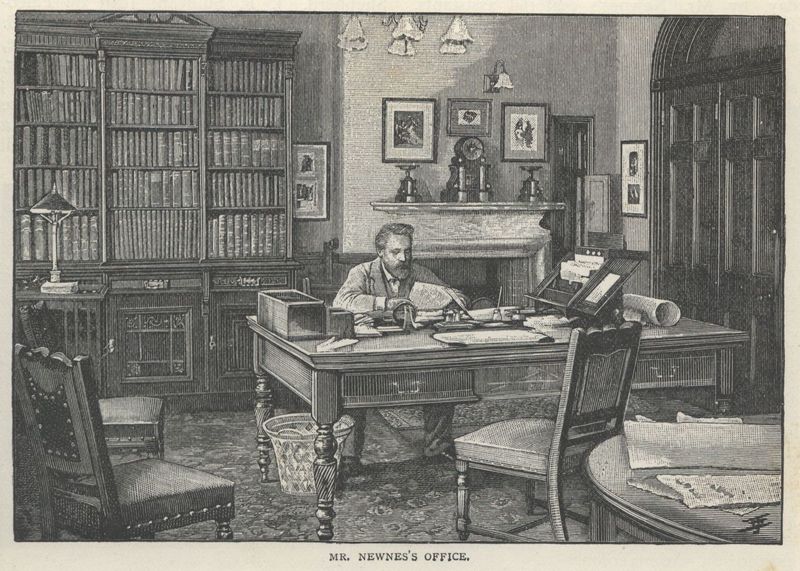

Figure 2 – Illustration by A. J. Johnson titled "Mr. Newnes's Office" from "A Description of the Offices of The Strand Magazine" in The Strand Magazine, volume four (1892).

THE STRAND MAGAZINE—

AN INTRODUCTION

❈

In the introduction to the first volume of The Strand Magazine (1891-1950), George Newnes, founder and publisher of the magazine, wrote that he believed “The Strand Magazine [would] soon occupy a position which [would] justify its existence,” despite the “immense number of existing Monthlies” (3). His hopeful sentiment would soon reach both short-term and long-term fulfillment. The first issue of The Strand would sell extraordinarily well, and the magazine would be in circulation until 1950, a total of 59 years. Prior to founding The Strand, Newnes had already found success as a publisher with Tit-Bits from all the interesting Books, Periodicals, and Newspapers of the World (1881-1984). Tit-Bits was a penny-weekly aimed at giving “light reading” to “superficial readers” (Newnes qtd. in Pittard 2) after the introduction of the Education Act of 1870, and issues would sometimes peak at a circulation of 900,000 copies (“Tit-Bits”). Despite this success, Newnes felt there was a gap in the market for a periodical purely dedicated to the aspirational middle-classes of London (Pittard 2).

In Mirror of the Century: The Strand Magazine 1891-1950 (1966) Reginald Pound, editor of The Strand from 1941 to 1946, notes that Newnes had been heavily influenced by popular American magazines of the time, including titles such as Harper’s and Scribner’s, and feared these titles would soon become more popular in Europe, taking precedence over British titles (30). With a specific demographic in mind, clear international influences that he felt were superior to British-born titles, and thus a want to feature British middle-class tastes, prejudices, and values, The Strand was conceived. By December 1890, the January 1891 issue of The Strand had hit the market. Sold for six pence a copy, this first issue would reach a circulation of roughly 300,000 copies (“Strand Magazine, the”). The Strand was met with fair positivity in key early reviews of the magazine, described as containing “excellent” illustrations (“Our Library Table”), having “bright and interesting articles” (“Our Library Table”) and as being “a wonderful sixpennyworth” (“Book Review”). In one particularly positive review that followed the first issue, the reviewer observes that “the paper is good, and the illustrations numerous and pleasing; it is something like a sixpenny English edition of Scribner or Harper, a cross, perhaps, between the French illustrated magazine and the American monthlies” (Stead, "The Strand Magazine," vol. 3, no. 13, 29). The Strand was clearly well-received, and Newnes’s careful consideration of overseas popular literature was apparent in his work.

With the initial and growing success of The Strand through the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, the magazine stood out against the “immense number of existing Monthlies," as Newnes had initially said it would. The magazine would soon see high-profile political figures as contributors, including Queen Victoria and Winston Churchill. The magazine would also publish early works of key literary figures, such as Agatha Christie, H. G. Wells, and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. The magazine became a mirror for the middle-classes of England, through which they saw themselves clearly represented unlike any other title available to them (Pound 7). This led to a large and loyal readership unprecedented by any other national magazine (9). The Strand would eventually grow to such popularity that it became a symbol of Englishness, representing a sense of shared community among its readers. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, best known for his Adventures of Sherlock Holmes series, of which over fifty stories were published in various issues of The Strand, articulated the sense of community that the magazine represented:

[Arthur Conan Doyle] later wrote of his journey in a letter to the literary editor of The Strand Magazine, remarking that 'Foreigners used to recognise the English by their check suits. I think they will soon learn to do it by their Strand Magazines. Everybody on the Channel boat, except the man at the wheel, was clutching one.' (qtd. in Pittard 1)

I. A Brief Overview of the First Volume of The Strand Magazine

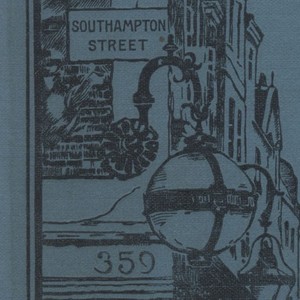

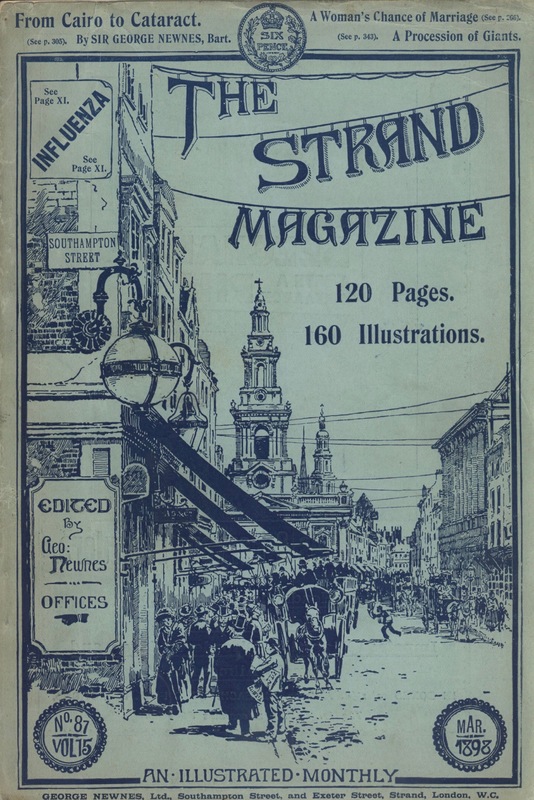

A copy of the January 1891 issue of The Strand is held at Special Collections at The University of Victoria, bound within a six-month volume that includes the first six issues (figure 1). Special Collections contains a wide selection of volumes through the magazine’s entire date-range of 1891 to 1950. The collection also holds one single issue, number 87 from March 1898 (figure 11). While this exhibit focuses on volume one, volume four is also used to provide images and contextualization, and issue 87 is used to compare the single-issue to the six-month volumes.

The first volume of The Strand contains issues one (January 1891), two (February 1891), three (March 1891), four (April 1891), five (May 1891), and six (June 1891) bound by a dark, muted blue hardcover. The cover design, illustrated by George Charles Haité and discussed in detail in the second section of this exhibit, is drawn in black ink. The volume measures a width of 20.6 centimetres, a height of 25.8 centimetres, and a depth of 5.4 centimetres, so it is of a considerable size that lends itself more to being displayed and kept at home, rather than easily carried around as the monthly issues would have been. The spine reinforces this conclusion, as it is decorated with black, but mostly gold, ink. There are a number of decorative details inside of the volume as well. In developing The Strand, Newnes’s goal was for every page of every issue to contain at least one illustration, which no other publication at this time had achieved (Pound 30). While Newnes quickly learned that this was not practical (30), these first issues still contain reproductions of pictures and illustrations on almost every page. For example, the “Introduction” page shows a beautifully decorated floral headpiece that extends down to the decorated initial letter “T” (figure 3). Other examples include a tailpiece that reads “finis” and appears to have pages of unknown publications thrown together in a chaotic pile (figure 4), and a headpiece showing a sixteenth-century illustration of The Strand (figure 5), both from “The Story of The Strand” and illustrated by Haité. Interestingly, the images contained in The Strand are incorporated into the text, rather than placed as secondary additions to the text. The images are almost always in direct relation to the corresponding text; an example of this relationship involves the aforementioned headpiece as it is a historical depiction of The Strand placed within “The Story of The Strand,” an essay that details the history of The Strand. Illustrators are also given credit for their work alongside authors in most cases. These observations, along with Newnes’s original goal to publish a periodical with an illustration on every page, suggest that the illustrations were equally important as the text.

❈

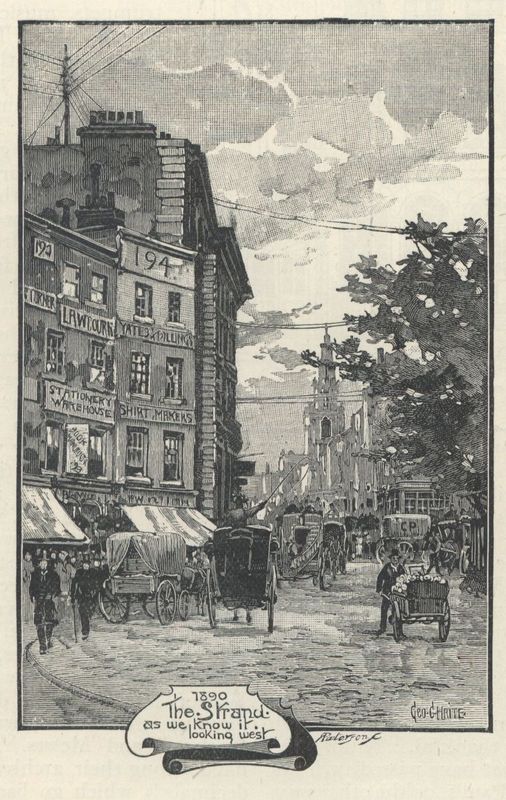

Figure 6 – Illustration by George Charles Haité captioned "1890 The Strand as we know it, looking west" from "The Story of the Strand" in The Strand Magazine, volume one (1891).

Figure 7 – "The Strand, Looking Eastwards from Exeter Exchange," Wikimedia Commons.

Dated 1824, the painting shows The Strand from an almost identical location and angle as Figures 1 and 6.

LOCATION

“The Strand is a great deal more than London’s most ancient and historic street: it is in many regards the most interesting street in the world.”

("The Story of The Strand" 4)

❈

I. Choosing to name The Strand after The Strand

In notes for an autobiography that was never completed, Newnes once argued that the name of a periodical was not integral to its success: “The name of a periodical does not really matter so much as people imagine. If you put such material into the pages as will attract the public, they become so accustomed to the name that after a while it really signifies very little whether the title be a good or bad one” (qtd. in Pound 31). However, he meticulously rejected many titles before finally deciding on The Strand (31). While he was explicit in his belief that the content of a magazine should captivate its readers, Newnes was remarkably specific and strategic in choosing to name his new periodical after Strand Street in London (the street commonly referred to as The Strand). The Strand’s influence on the magazine is seen in a great deal more than the title. Newnes and the team behind The Strand wove this location throughout various aspects of the publication. One example in particular includes the first article in the first volume of the magazine. The essay is titled “The Story of The Strand” and provides a highly detailed look at the history of The Strand. Here, the author describes The Strand as being “a great deal more than London’s most ancient and historic street: it is in many regards the most interesting street in the world” (“The Story of The Strand” 4). The author continues to argue that “it would be impossible to find a street more entirely representative of the development of England than the long and not very lovely Strand” (13). Knowing aspects of Newnes's goals behind founding The Strand, particularly his goals of wanting to appeal to a specific British middle-class audience, coupled with his commitment to reflect British ideals to prevent international titles from infiltrating the market, it appears that his choice to centre his magazine around a specific London location with a deep history and nationalistic reputation was likely an extremely calculated decision.

The Strand was not the first magazine to be linked location, nor was it the only one popular at the time. Three prominent examples, in chronological order by the first date of publication, include Athenaeum (1828-1921), Cornhill (1860-1975), and Belgravia (1867-1899) [1]. Athenaeum, London Literary and Critical Journal was a weekly created by James Silk Buckingham; however, he left the publication within the first two years and the periodical was taken over by Charles Wentworth Dilke (Brake and Demoor 26). At the time of initial publication, the weekly cost eight pence, and its circulation dramatically altered throughout the years, ranging anywhere between 500 and 18,000 copies (“Athenaeum, The”). Second, Cornhill Magazine (1860-1975) was founded by George Murray Smith. Cornhill was a shilling monthly magazine that catered to a broad middle-class audience (Brake and Demoor 145). The magazine began with a circulation of around 110,000, and was able to maintain a circulation of 80,000 for the first two years, after which, circulation steadily declined (145). Similarly, Belgravia: A London Magazine (1867-1899) was a shilling monthly founded by John Maxwell. The magazine reached a circulation of 18,000, and averaged a circulation of 15,000 before steadily declining in the 1870s (145).

Athenaeum, Cornhill, and Belgravia were each named after a specific geographical location that represented the core values their founders sought to exhibit through their publications, as well as inspired the potential reputation each title would eventually have. Athenaeum derived its name from the Ancient Roman school Athenaeum, and its founders wanted it to be “worthy of the name, and, like the Athenaeum of antiquity, should become the resort of the most distinguished philosophers, historians, orators, and poets of [their] day” (unknown qtd. in Marchand 1). Cornhill was named after publisher Smith’s own address of 65 Cornhill, London (Schmidt 203). The magazine became well-known for its pure, family-friendly content (Brake and Demoor 145) that depicted Cornhill as a place of hard work that would lead to a prosperous outcome (Schmidt 203). Belgravia, more expensive than The Strand at one shilling, was named after one of the wealthiest districts in London, and the magazine appealed to a more bourgeois readership (Cooke). Clearly seen by observing their dates of publication, these magazines were popular enough to have been in circulation for a number of years, the shortest being Belgravia at 32 years, and the longest being Cornhill at 115 years. However, while each one was popular among its intended imagined readership, not one reached the same level of success as The Strand.

[1] Special Collections at The University of Victoria holds physical copies of Cornhill Magazine. Microforms holds microfilm copies of Athenaeum, London Literary and Critical Journal and Belgravia: A London Magazine. The selections of issues from Cornhill are dated throughout its entire publication run between 1860 and 1977. The copies on microfilm from Athenaeum are dated between 1830 and 1921. The copies on microfilm of Belgravia are dated throughout its entire publication run between 1867 and 1899.

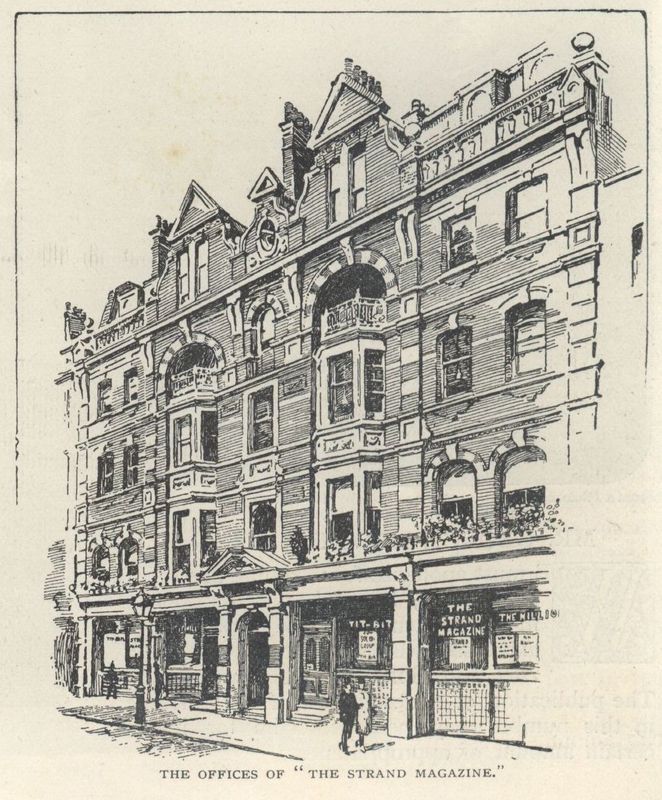

Figure 8 – "The Offices of 'The Strand Magazine'" from "A Description of the Offices of The Strand Magazine" The Strand Magazine, volume four (1892).

II. Inserting The Strand into The Strand – The Self-Reflexive Nature of The Strand

In addition to the title of the magazine, perhaps one of the more obvious examples of its connection to The Strand is the famous front cover, illustrated by George Charles Haité. Haité’s depiction places the observer at ground-level on Strand Street, looking West toward the Royal Courts of Justice and the church of St. Mary-le-Strand (figure 1). He illustrated a similar piece for “The Story of the Strand” (figure 6), and when both of these illustrations are compared to other depictions of this location (such as figure 7), we can see that Haité took care to be geographically correct. By doing so, readers who had been to Strand Street, or who have seen depictions of it, could easily place the recognizable location. The small sign on the left of the cover reads “Southampton Street” (figure 9). Southampton was the street that the George Newnes, Limited offices were located on. This connection is further emphasized by the number “359,” which was the building number of the offices, and even more explicitly shown through the sign reading “offices” with a hand pointing to the left. Notably, some early issues of The Strand showed a sign that read “Burleigh Street” rather than “Southampton Street.” Burleigh is the street that actually intersects with The Strand, roughly in this area, so while this version of the cover was perhaps more geographically correct, it was less self-reflexive. Finally, Haité intigrates the title of the magazine into the scene, as each letter hangs from the overhead telegraph wires.

The self-reflexive nature of connecting The Strand to The Strand is carried within the text as well. In “The Story of the Strand,” the text opens with a decorated initial “the” (figure 10). These decorative letters are placed against a background comprised of the cover of The Strand Magazine, a copy of Tit-Bits, and a flyer for the publication’s office. By placing a copy of The Strand within “The Story of the Strand,” an essay detailing the history of Strand Street, Newnes asserts that his publication will be more than just simply influenced by this specific location, but will rather become a part of its history. He establishes The Strand as being intrinsically connected to this location while suggesting that it can also influence the location's history through its readership. As the author states that The Strand is “the most characteristic and distinctive” of London (13), Newnes prepares The Strand for being equally as characteristic and distinctive of London and its people.

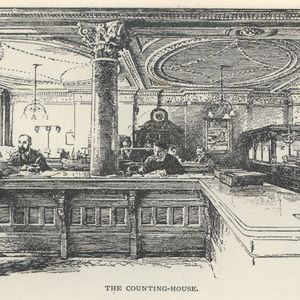

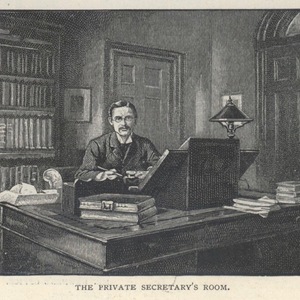

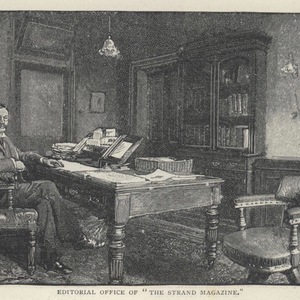

The above illustrations by A. J. Johnson were selected from "A Description of the Offices of The Strand Magazine," an article in the fourth volume of The Strand Magazine. The article explains how interested readers are concerning what goes on behind the scenes of The Strand: "Visitors to these offices have so much interest, and letters of inquiry have so constantly reached us from those who are unable to come themselves, that we think no apology is needed for the following brief description of the work involved in producing The Strand Magazine and its fellow publications" (594).

❈

Figure 11 – Front cover of The Strand Magazine, issue 87 (1898).

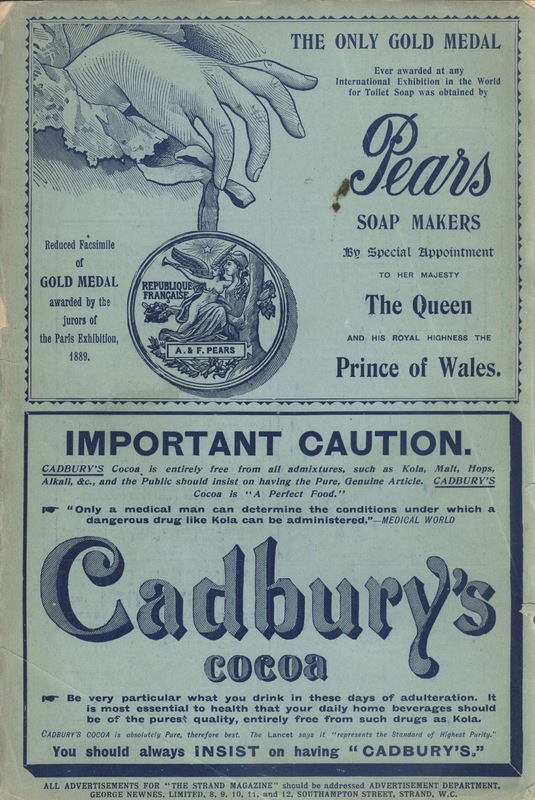

Figure 12 – Back cover of The Strand Magazine, issue 87 (1898).

REMEDIATION

“The modern reader of nineteenth-century periodicals is, however, confronted with a paradox. The physical objects with which we have to deal are likely to be the bound volumes on the library shelves. The nineteenth-century middle-class habit of binding favourite periodicals in volume form has ensured that vast numbers still survive, though the crumbling paper inside the covers bears witness that stay of execution is only temporary. However, it is these volumes which provide our texts.”

(Beetham 23)

❈

I. Periodicals and Time

Contemplation on the remediation process is integral to understanding how The Strand developed itself into being a national signifier through reproducing the values of the middle class. In short, the remediation process involves transforming one form of media into another; here, the term is used to discuss the different mediations of a magazine, particularly the single-issue form, the volume form, and the digital form, with a focus on what is changed or kept the same from form to form. The different mediations of the magazine can work both independently and dependently to produce and reproduce meanings, shaping identities on individual and communal levels. The majority of the copies used in this exhibit have themselves been remediated. While The Strand was released in monthly instalments that were “issued regularly in the early part of each month” (Newnes 3), the magazine would later be bound into six-month volumes.

In “Towards a Theory of the Periodical as a Publishing Genre” (1990), Margaret Beetham asserts that the periodical genre is intrinsically linked to time, time being the defining characteristic of the genre (19). Released at specific intervals, whether it be daily, weekly, or monthly, these magazines become a regularly-scheduled occurrence in the day-to-day lives of many. Beetham refers to them as “the first date-stamped commodity,” that was “designed both to ensure rapid turnover and to create a regular demand” (21). She refers to them as “read today and rubbish tomorrow [texts]” (19), where readers are expected to buy their issue, consume it, and then move on to buying the next. Similar to how, with newspapers, content would be time-sensitive, a periodical’s content could become “old” by the next issue’s release. It did not necessarily matter that magazines such as The Strand included content that we now know would still be read in the twenty-first century, such as Arthur Conan Doyle’s “A Scandal in Bohemia” in the seventh issue, as it was often the format of the magazine that would necessitate its temporary status. Utilizing cheaper paper and a lack of hardcover for mass distribution (22) meant that for the average reader who was not extremely careful with his or her copy, it would not last. Preservation was not the goal of these commodities, though, as the goal was to keep readers interested enough to buy the next issue.

In “Cohering Knowledge in the Nineteenth Century: Form, Genre and Periodical Studies” (2009), James Mussell takes a similar approach to periodical studies as seen in Bentham’s work. Still on the subject of time, Mussell argues that periodicals sold their new content in old and established ways; periodicals would adopt reoccurring structures, such as categories that would remain the same throughout the entire run, but would change the content within each category, making new content have a sense of familiarity to the reader (95). As a result, future unknown content would already have a place within the magazine, as long as it could relate to some theme already within the magazine (97). Beyond categories as a means of familiarity, many periodicals would use serials to drive a continued readership. Newnes, however, wanted each issue to be organically complete, and made the choice to avoid serials (Pound 30). This did not mean that each issue was not deeply connected to past and present issues. For example, each issue of The Strand contained an immensely popular article titled “Portraits of Celebrities at Different Times of their Lives.” Each issue would feature three-to-five portraits of a handful of celebrities at various points in their life, along with a short biography. Frequent consumers would come to expect content such as this.

II. Remediating The Strand

Despite the disposable nature of periodicals, it was a habit of the nineteenth-century middle-class to bind their issues into volumes as a means of preservation for these texts (Beetham 23). It is in this sense that the concept of time takes on a complex dual role. Looking at The Strand, we begin with the monthly issue that utilized cheaper paper, a lack of hardcover, and was filled with advertisements, everything signaling a sense of temporariness and a need to last only until the next issue. However, we then see the monthly issue being bound alongside five other issues. After this process, the physical product no longer feels temporary, but rather something stable. At the crux of Beetham’s argument is her noting of the importance of what is not considered to be worth preserving and is instead left out of these bindings, most often being endpapers and advertisements (23), as is the case with The Strand. Similarly, Mussell observes these changes, adding that along with the removal of content, content such as prefaces, indices, or supplemental issues were often added into the volumes (94). We can see from the first volume that all advertisements were removed from each of the six issues, [1] and that the front cover was stripped to remove any issue-specific content. For example, a note advertising “120 pages” and “160 illustrations” was removed (figure 13), the price of six pence for the issue was removed (figure 14), and a note that reads “influenza” and “see page xi” was removed (figure 15). Each of these examples are an attempt to advertise the content of the magazine to a potential buyer, so the removal of this content suggests differences in how the six-month volume was advertised and distributed. A consumer at a railway station, a location issues of The Strand were sold (Pittard 2), would perhaps see “influenza” and wonder what was on page xi, or would see the advertisement for the amount of illustrations, along with the price, and would want to pick up their own copy. However, the six-month volume does not need to be marketed in this way. The content of the issues has already been published, but now it must be preserved.

In addition to their connection to time, periodicals are also intertextual in nature. Each text can generate meaning, but when these texts are placed alongside each other they appropriate and absorb each other, and do so in relation to their placement in the periodical format (Brake 55). Essentially, when you are reading a short story that is published within a periodical, you are not reading that story in isolation, and that story does not generate one particular meaning based on that text alone; instead, that story draws meaning from the texts and images published alongside it in the issue, as well as from the periodical as a whole. In the process of remediating the text from single-issue to six-month volume, these meanings are further renegotiated (Beetham 23). Beetham argues that this shift suggests each issue of the periodical is incomplete until it is bound together and preserved as a whole; however, this occurs at the cost of the issue’s original form (23). Meanings become renegotiated as they are now consumed in something that is presented as long-lasting and complete, as well as the different texts now appropriating and absorbing each other. Further, these meanings become renegotiated through the exclusion of what is not considered worth preserving. In the case of The Strand, it is the advertisements that are excluded.

Using issue number 87 from March 1898 as a representative example of what was excluded from the six-month bindings, the issue contains 52 pages dedicated exclusively to advertisements, split between two sections at the front and back of the magazine. The inside of the front cover as well as the entire back cover are also filled with advertisements. The advertisements spread to fill the extra space on the contents page. Advertisements range in content, some examples include: a small advertisement for The Fairy Belt, a corset from Hindes, Limited that promises to “[change] the shape of the waist from oval to round”; a half-page advertisement for Cadbury’s Cocoa, warning consumers to “be very particular what you drink in these days of adulteration” (figure 12), to a to a full-page advertisement for Williams’ Shaving Stick that claims to be “incomparable for its great, creamy luxurious lather” (examples of these advertisements can be seen in the gallery below). However, despite these advertisements filling up 52 out of a total of 120 pages in the issue, not one is carried over into the six-month volume.

[1] Reginald Pound’s Mirror of the Century: The Strand Magazine 1891-1950 (1966) features scans of the advertisements from the first issue (January 1891) of The Strand Magazine.

The series of images above are advertisements from issue 87 of The Strand Magazine.

❈

Final Connections

“It may be said that with the immense number of existing Monthlies there is no necessity for another. It is believed, however, that The Strand Magazine will soon occupy a position in which will justify its existence.”

(Newnes 3)

❈

I. The Strand as Community-Building and the Periodical as Meaning-Making

Before the publication of the first volume of The Strand Magazine, Newnes had sensed a gap in the market for a British periodical that would appeal to the aspirational middle class (Pittard 2), that would take influence from foreign titles (Pound 30), and one that would prevent the people of Great Britain from seeking publications from overseas. By looking at the success of the first volume of The Strand, we can conclude that Newnes was correct about that gap. Through deep connections between The Strand and The Strand, Newnes was able to build an imagined community of readers; although not every contemporary reader of this first volume lived on Strand Street, nor even lived in London, the magazine connected each and every reader to that location. If, following the work of scholars like Beetham and Mussell, we consider periodicals to be intrinsically connected to time, intertextual in nature, and able to derive meaning through various remediations of the text, how does this imagined community of readers fit? As both Beetham and Mussell observe, remediations can create different meanings through the removal or addition of material (Beetham 23; Mussell 94). With the initial first issue of The Strand, readers experienced Strand Street not only through the images and texts inside the periodical, but also through the physicality of the temporary object, and the products advertised. With the remediation to the six-month volume, this representation that is presented to readers is now something stable. Further, by incorporating self-reflexive elements to his work, Newnes was able to insert The Strand into the history of Strand Street from the first issue. By doing so, he also placed each and every one of his readers into this history. Contemporary readers were able to derive meaning from each article in relation to both the periodical genre and Strand Street, but Strand Street has derived meaning from its focus in The Strand. Both The Strand and The Strand were able to develop over time, whilst influencing the histories, reputations, and stories told of the other. Through the specific appeal to the middle-class reader, contemporary readers were able to see a “[clear] image of themselves in print” (Pound 7), and that image involved a connection to a physical location they may have never visited.

Figure 17 – My remediation and interpreted meaning of the first volume of The Strand Magazine.

By placing my work within my work, I am mimicking the self-reflexive nature of The Strand.

II. Final Remediation—Conclusion

The third step in this process is digitalization, and for this step I will use this very exhibit as an example. Through the general theme of readership, I have examined how The Strand was centred around Strand Street, a specific geographic location. I have argued that The Strand was self-reflexive as it placed itself in its own work that discusses or depicts Strand Street, and therefore placed itself within the history of The Strand. These observations, coupled with the popularity of the magazine, developed a widespread community of readers who were (and are) able to renegotiate meanings of The Strand based on The Strand, and vice versa. Further, I have looked at how the remediation process from single-issue to six-month volume has renegotiated these meanings. Throughout this argument I have pulled material, both visual and textual, from multiple volumes of The Strand. I have described the physical features of the first volume, and provided context on Newnes’s vision for this early work. I have included content from a single issue of The Strand, and compared it to the volumes. And finally, I have provided contemporary reviews and scholarly research throughout. I have provided my own remediation of The Strand, and throughout this process I have pulled these materials as a means to negotiate my own meaning. Beetham observes that the remediation of a text from single-issue to six-issue volume is done to preserve the text (23), so digitization is a way to further preserving the text and discover new meanings. This exhibit is placed alongside other exhibits in Movable Type: Print Material in Special Collections, each focused on a different object held within The University of Victoria’s Special Collections. Beetham argues that the magazine format invites intertextual readings of each text in relation to those it has been bound with, as well as the magazine as a whole, of which each text is a part (55). Therefore, the meaning of this digital remediation absorbs and appropriates the works that it is presented alongside, further renegotiating both meanings.

❈

❈

Find The Strand Magazine:

The University of Victoria's Special Collections holds a number of volumes of The Strand Magazine, along with one single issue. For access online, Project Gutenberg shares a selection of volumes, and Archive.org shares digital flipbooks of some volumes.

See related texts in The University of Victoria's Special Collections for further reading:

Special Collections also holds a number of illustrated late-nineteenth century periodicals, some of which include: Cornhill Magazine (1860-1975), The Savoy (1896), and The Yellow Book (1894-1897).

See related projects from Movable Type: Print Material in Special Collections:

There are a number of wonderful exhibits held within this collection. For recommendations that are similar to aspects of this page, I recommend the following:

HOUSEHOLD WORDS, CONDUCTED BY CHARLES DICKENS (1850-59)

For another nineteenth-century periodical.

WILKIE COLLINS - THE WOMAN IN WHITE. SERIALIZED IN ALL THE YEAR ROUND, EDITED BY CHARLES DICKENS. (1859-60)

For serialized work in a nineteenth-century periodical.

❈

❈

Acknowledgements

I would like to personally thank the team at The University of Victoria's Special Collections for their help with the completion of this exhibit. Also, I extend my thanks to Doctor Alison Chapman for her direction on this project; her insight and feedback throughout this project's development was immensely helpful, and is much appreciated. Further, I would like to thank the rest of my ENGL500 peers for their feedback and encouragement, as well as for sharing their wonderful projects.

❈

Works Cited

"A Description of the Offices of The Strand Magazine," illustrations by A. J. Johnson. The Strand Magazine, edited by George Newnes, vol. 4, Jul.-Dec. 1892. George Newnes, Limited. Special Collections, University of Victoria, Victoria, call number: AP4 S8.

"Athenaeum, The." The Waterloo Directory of English Newspapers & Periodicals: 1800 – 1900. Accessed 17 Nov. 2017.

Beetham, Margaret. “Towards a Theory of the Periodical as a Publishing Genre.” Investigating Victorian Journalism, edited by Laurel Brake, Aled Jones, and Lionel Madden, The MacMillan Press Ltd., 1990, pp. 19-32.

“Book Review.” The Athanaeum, no. 3294, 13 Dec. 1890, p. 815. Accessed 17 Nov. 2017.

Brake, Laurel. “Writing, Cultural Production, and the Periodical Press in the Nineteenth Century.” Writing and Victorianism, edited by J. B. Bullen, Longman, 1997, pp. 54-72.

Brake, Laurel, and Marysa Demoor. Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century Journalism in Great Britain and Ireland. Academia Press, 2009.

Cooke, Simon. "Belgravia: A London Magazine." The Victorian Web, 5 Jun. 2014. Accessed 30 Nov. 2017.

Marchand, Leslie A. The Athenaeum: A Mirror of Victorian Culture, The University of North Carolina Press, 1941.

Mussell, James. “Cohering Knowledge in the Nineteenth Century: Form, Genre and Periodical Studies.” Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 42, no. 1, 2009, pp. 93-103.

Newnes, George. "Introduction." The Strand Magazine, edited by George Newnes, vol. 1, Jan.-Jun. 1891. George Newnes, Limited. Special Collections, University of Victoria, Victoria.

“Our Library Table.” The Athenaeum, no. 3324, 11 Jul. 1891, pp. 60-61. Accessed 17 Nov. 2017.

Pittard, Christopher. “‘Cheap, Healthful Literature’: The Strand Magazine, Fictions of Crime, and Purified Reading Communities.” Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 40, no. 1, 2007, pp. 1-23.

Pound, Reginald. Mirror of the Century: The Strand Magazine 1891-1950, A. S. Barnes and Co., Inc., 1966.

Schmidt, Barbara Quinn. “Introduction: ‘The Cornhill Magazine’: Celebrating Success.” Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 32, no. 3, 1999, pp. 202–208.

Stead, William Thomas. “The Strand Magazine.” The Review of Reviews, vol. 3, no. 13, Jan. 1891, p. 29. Accessed 17 Nov. 2017.

———. “The Strand Magazine.” The Review of Reviews, vol. 3, no. 18, Jun. 1891, p. 580. Accessed 17 Nov. 2017.

“Strand Magazine, The.” The Waterloo Directory of English Newspapers & Periodicals: 1800 – 1900. Accessed 17 Nov. 2017.

"The Story of The Strand." The Strand Magazine, edited by George Newnes, vol. 1, Jan.-Jun. 1891. George Newnes, Limited. Special Collections, University of Victoria, Victoria.

The Strand Magazine, edited by George Newnes, vol. 1, Jan.-Jun. 1891. George Newnes, Limited. Special Collections, University of Victoria, Victoria, call number: AP4 S8.

The Strand Magazine, edited by George Newnes, vol. 15, no. 87, Mar. 1898. George Newnes, Limited. Special Collections, University of Victoria, Victoria, call number: AP4 S8.

“Tit-Bits.” The Waterloo Directory of English Newspapers & Periodicals: 1800 – 1900. Accessed 17 Nov. 2017.

Works Consulted

Anderson, Patricia. “Illustration.” Victorian Periodicals and Victorian Society, edited by Rosemary T. VanArsdel and J. Don Vann, University of Toronto Press, 1994, pp. 127-142.

Cranfield, J. L. “Arthur Conan Doyle, H. G. Wells and The Strand Magazine’s Long 1901: From Baskerville to the Moon.” English Literature in Transition, 1880-1920, vol. 56, no. 1, 2013, pp. 3-32.

Hale, Ann M. and Shannon R. Smith. “’You see, but you do not observe’: Hidden Infrastructure and Labour in the Strand Magazine and Its Twenty-First Century Digital Iterations.” Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 49, no. 4, 2016, pp. 664-693.

Fyfe, Paul. By Accident or Design: Writing the Victorian Metropolis, Oxford University Press, 2015.

KF/Fall 2017