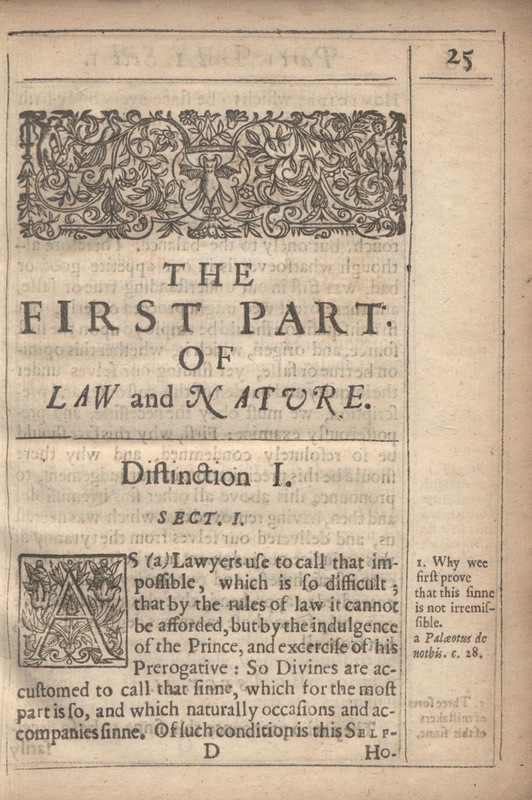

John Donne's Biathanatos (1648)

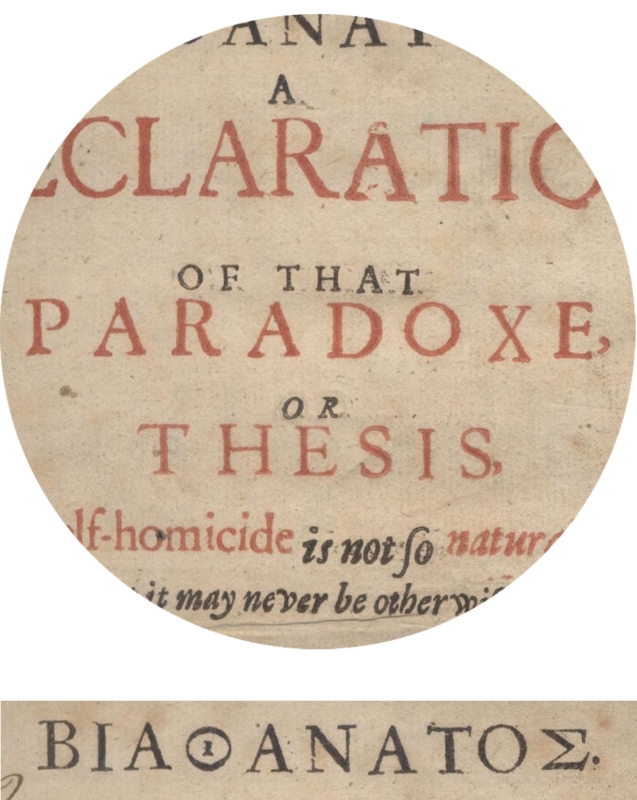

Fig 1. Title page of John Donne's 1648 edition of Biathanatos at the University of Victoria.

Fig 2. Portrait of John Donne from the National Portrait Gallery, London UK. NPG 6790. License.

Printers and Paradoxes

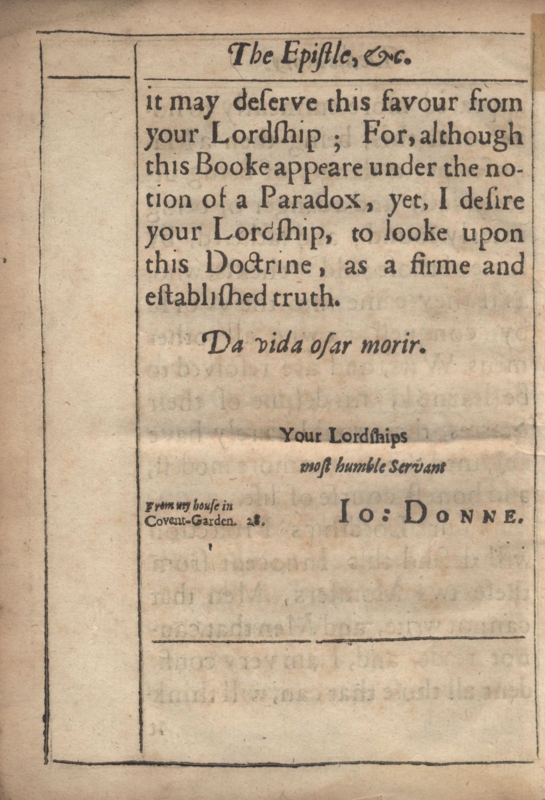

"For, although this Booke appeare under the notion of a Paradox, yet, I desire your Lordship, to looke upon this Doctrine, as a firme and established truth."

❦

So ends the dedicatory epistle John Donne's son wrote to Lord Phillip Harbert when he sought approval to publish his father's highly controversial Biathanatos, a work named after the Greek word meaning a "violent death." Arguing against the presumed sinfulness of suicide—or self-homicide as this act was called in the seventeenth century—this book participates in the complex political and theological tensions of early modern London. The assertion of truth in this opening letter takes a bold and provocative stance, questioning knowledge during the Civil War (1642–1651) and a precarious time of censorship and religious conflict.

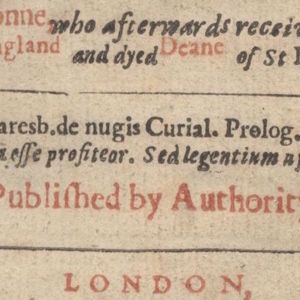

Written by the influential John Donne (1572-1631), who also served as the Dean of St. Paul's Cathedral, Biathanatos existed only in manuscript form after the poet's death. The two earliest surviving versions of the book bear the dates 1644 and 1648, but many scholars believe these copies were both first printed in 1647 (Sullivan 63-4). The book would later be printed again in 1700, creating a history of printing that indicates the text had enough popularity—or notoriety perhaps—to inspire revived readership for over half a century.

The edition of Biathanatos in Special Collections at the University of Victoria includes the 1648 date on its title page, situating it at a crucial time when the Civil War limited resources and heightened social and political conflict. Who would print and read such a controversial book at this time? It is impossible to know precisely who read Biathanatos, but the edition in Special Collections offers evidence that makes it possible to trace the types of readers who might have been drawn to it. This examination will show how the layout of each page speaks to the printer's imagined audience and how the introductory material that accompanies the main text illuminates Donne's ideal reader, even if he never intended to publish the work. The controversial book further reveals how authors, printers, publishers, and readers interacted in the seventeenth century and positions these individuals in conversation with one another.

The materiality of the book and its social context reveal the various types of readers imagined during the long process that brought Biathanatos from its manuscript to the printer and, finally, to a wider audience. Understanding how Biathanatos crafts an imagined reader is crucial not only for locating Donne's work in a vital theological conversation but also for examining how the materiality of the book reaffirms and echoes its arguments.

Art and Argument

i. The Rhetorical Page

In his efforts to persuade readers of the theological acceptability of suicide, Donne employs rhetorical language and structures that make it difficult for readers to doubt or contradict the authority of his claims. The printer's conception of Donne's work complements this argumentative stance and blends art and argument in the very material representation of the text.

Since the book was published posthumously, the printed versions of Biathanatos that emerged in the 1640s were created without the author's direct involvement. How did the printer interpret the manuscript copy, and what imagined reader did the printer have in mind when producing the copy now preserved at the University of Victoria?

This edition of Biathanatos is a quarto, meaning its pages were made by folding large sheets of paper into quarters. As paper was the most expensive cost of printing (Levy and Mole 77), the resulting pages could be compiled into generally cheaper books. The economical use of space on these small pages further suggests that the book was not meant to draw attention to itself as a gift or decorative book might; rather, Biathanatos appears logical, solemn, and practical, echoing the rational attitudes its content espouses.

ii. Of Grids and Hierarchies

The authoritative tone created through the structure of the book is linked to its transition from manuscript to print. As Mark Bland writes, printed books employ a strict layout that necessitates repetition and order: "The rigid structure of the page, and the consistency of letterforms introduced a precise and ordered structure to the printed book; whereas, with manuscript, variation was inevitable" (118). In Biathanatos, the orderliness of the printing press is evident in the grid-like appearance of the text, which is organized into dense and uniform lines. The precision of the letters imbues the book with a similar sense of order, creating an impression of authority—both figuratively and literally as the type pressed ink into the page—before the reader even interprets its content.

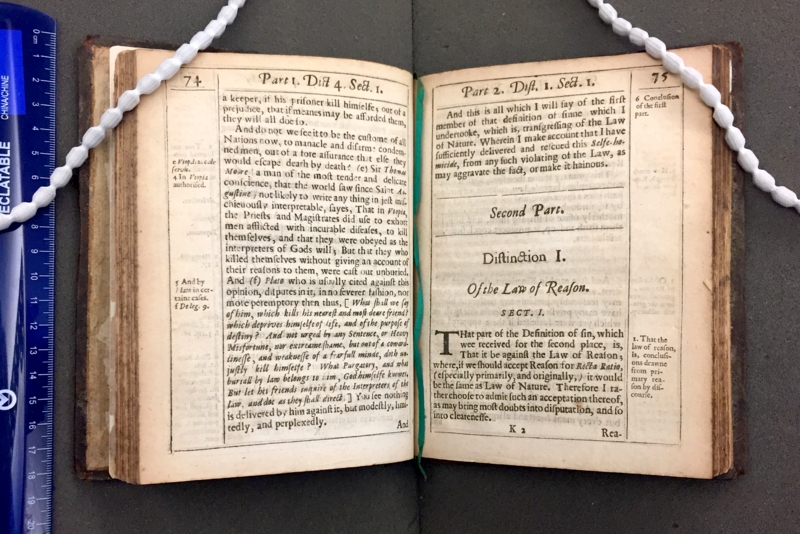

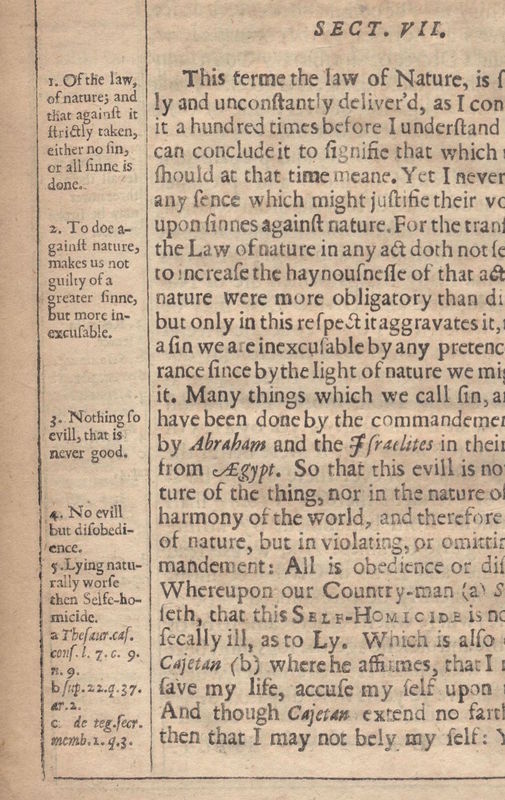

These blocks of text are further enclosed in dark black lines that divide the page. In figure 3, each section of text occupies a clearly defined space: the main body of the work is located in the largest box, annotations are constrained to the narrow right column, section headings are included in the largest upper area, and page numbers appear in the upper right corner. Organizing the page into visible compartments helps readers identify the relationships between these textual elements, especially as they could interpret these features from other books printed in the seventeenth century (see, for instance, figure 24). It is clear that reading is as much an act of interpreting the spatial relationships between words as an act of interpreting their semantic meanings. Such organization indicates that the book was designed and printed in a way that aims to persuade audiences of its legitimacy.

Just as the page is divided into clear sections, the overall structure of the book contains a hierarchy of information. Biathanatos is divided into three main parts: "Of Law and Nature," "Of the Law of Reason," and "Of the Law of God." Not only are the titles formulaic in their structure, but each "part" of the book is further divided into "distinctions" which are then subdivided into "sections." The table of contents offers a detailed outline of these divisions, and glancing through the list makes it clear that each individual argument is given a well-defined space. The extensive numbering of these sections allows readers to see how ideas relate to one another hierarchically, encouraging them to make connections between broader arguments.

Fig 6. (Above) Printed marginalia in Biathanatos (page 36).

Fig 7-10. (Below) Detailed views of marginalia.

iii. Printed Marginalia

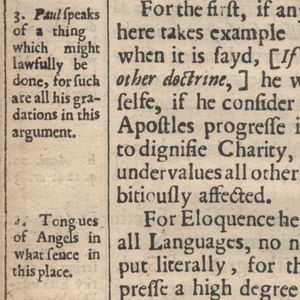

This hierarchy of information is then supplemented with notes printed in the right column with slightly smaller letters (see figures 6-10), which point readers to Donne's primary sources, explanations, and other information that supports the arguments of the main text. Marginalia often appears in early manuscripts that existed long before the printing press, and including them in early modern books was thought to establish a sense of authority. Examining the reasons that motivated printers to include such notes, William Slights argues that "a good way to make a book seem important and, hence, marketable was to accentuate its affiliation with older traditions of textual production" (3). The marginal notes in Biathanatos resemble those of an older manuscript, even if translated into type, and create an impression of authority that readers would have perceived. Even in modern books, the presence of footnotes in a critical edition implies a sense of authority even if the reader ignores them.

The margins of Biathanatos also contain notes marking where different sections of the argument begin, serving further organizational purposes. The eighth section listed under the preface, for instance, includes the heading "What reader I desire to have" (see figure 14), and a slightly modified version of this statement appears in the margin when Donne addresses the four types of readers (see figure 15). This structure is useful as the book guides readers through the various levels of the argument, making it possible to visually connect broad ideas with in-depth explorations. The book becomes persuasive, in part, because it remains accountable to its overarching structures and purposes.

A Note on the Origins of the Marginalia

While few seventeenth-century copies of Biathanatos survive, one of the most intriguing is the transcribed manuscript copy Donne Sr. gave to Lord Herbert, which is now housed in the Bodleian Library. Critic Edward Sullivan traces the history of this manuscript and states that it was transcribed by a professional copyist, but he notes that this manuscript also contains Donne Sr.'s own handwriting in the introductory letter, the marginal annotations, and a short "sixteen-word correction added to the text" (Sullivan 54). Scholars are unsure which manuscript served as the printer's copy and became the model for the first edition, but the early history of the text indicates that Donne was indeed responsible for the extensive annotations that contribute to the argumentative style of the book, and the printer's inclusion of such notes suggests that their imagined readers were similar.

"All aspects of the text's physical form are capable of constituting meaning. Choices of paper, format, type, ornament, illustration, binding and page layout were made by one or more agents, singly or collaboratively."

(Bell 632)

iv. First Impressions

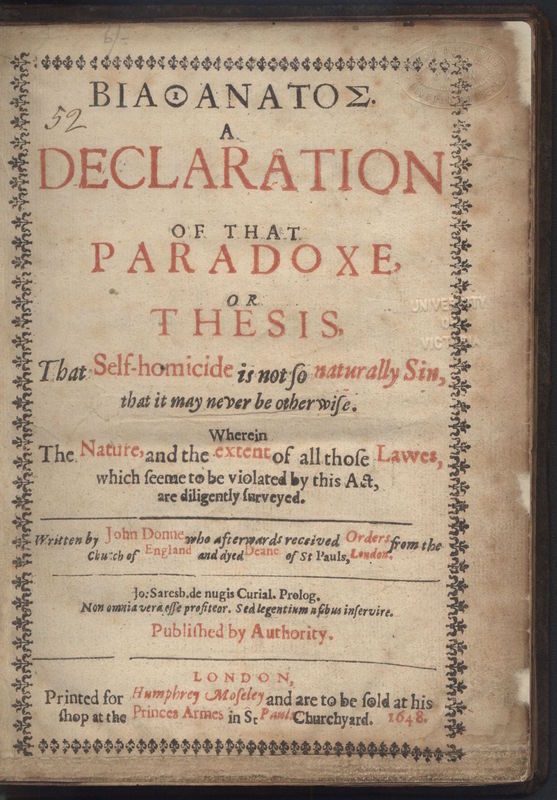

Among the most recognizable features, the printer's title page also serves important rhetorical purposes. This page includes a decorative border and unique typography that, alongside its use of Greek characters, manipulates the size, style, and colour of letters. The genre of the book is clearly forefronted, and the title page introduces readers to the key concepts of this theological thesis.

Presence and Absence

Emphasizing its genre with large capital letters, the title page declares that Biathanatos is itself a "DECLARATION." The most important features of early modern title pages were the title and publisher, with the "printer and author being of less significance and not always recorded" (Bland 66). The book therefore demonstrates the conventions of its time: the title is large and occupies most of the page, and the publisher's name is written in red ink for emphasis. Aligning still with typical practices, the printer's name is not included. The title page only diverges from common practices when it emphasizes John Donne's name with red ink. The attention given to the author may have been motivated by his contradictory role; the title page states that Donne held an important religious position, yet the book challenges established theological views.

Shifting attention away from the printer could function as a rhetorical move, particularly as it obscures the source of many stylistic choices regarding the material manifestation of the book. This decision may impact how readers interpret the text, but its effects are unclear. Does the erasure of the printer suggest that the material book has no origin? Could a book simply exist as a "firm and established truth" as Donne's son might believe in his dedicatory letter?

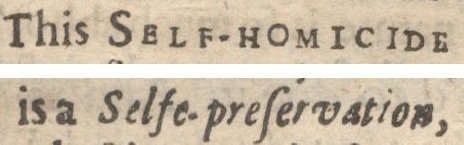

Much like the manipulation of font sizes, red ink also draws attention to key words on the title page. These words highlight the argumentative genre of the book by emphasizing words such as "declaration," "paradox," and "thesis." Red ink also identifies key subjects such as "self-homicide" and "naturally sin," and it points to important people associated with the book. These names include John Donne—who readers would have recognized from his influential poetry and sermons—alongside the prominent Humphrey Moseley, who published works by Milton, Middleton, and Beaumont and Fletcher. A reader could easily glance at the page and identify the most important features of the book, learning the genre, subject, and sources of the text without being burdened by extra details.

Advertisement

Extra title pages were often printed to serve as advertisements for early modern books, indicating that printers also needed to remain conscious of the intended reader for financial reasons. As Bland writes, "many title pages are explanatory, indicating the nature of their contents; ... for a prospective purchaser, these details gave a very brief synopsis of the nature of the material" (66). The title page already looks to attract readers both inside and outside the object of the book, serving not only as a label but as a means of encouraging readership as well. The full title of Biathanatos is transcribed below and offers a precise description of what the reader could expect:

ΒΙΑΘΑΝΑΤΟΣ.

A

DECLARATION

OF THAT

PARADOXE,

OR

THESIS,

That Self-homicide is not so naturally Sin,

that it may never be otherwise.

Wherein

The Nature, and the extent of all those Lawes,

which seeme to be violated by this Act,

are diligently surveyed.

These features of the title page, considered alongside the orderly structure of later pages, suggest that the printer was deeply invested in a presentation of the text that would attract readers who care about theological paradoxes and rhetorical exercises. It seems necessary that a book which discusses these ideas should also demonstrate logic and rationality. The material manifestation of this book parallels the logical and argumentative ideas that Donne circulated only in manuscript form during his life. The printer influences how readers interact with Biathanatos, guiding the reader through the text from the moment of seeing an advertisement to the final numbered leaf. Despite the printer's absence from the title page, this unidentified voice speaks to an ideal reader who also exists only in traces of evidence that the book preserves.

Spunges, Howre-Glasses, Bigges, and Sives

i. Pondering Paratexts

While much of Biathanatos is contained in the three major parts outlined earlier ("Of Law and Nature," "Of the Law of Reason," and "Of the Law of God"), the book is also composed of several additional interrelating texts, or paratexts, that serve different rhetorical and structural purposes. Gérard Genette identifies two unique types: peritexts, which exist within the book and include texts such as introductions and illustrations, and epitexts, which are located outside the book and might include interviews or journals (3-5). These materials, although diverse in type and function, all impact the reception of a book and shape how readers experience the perceived "main" text.

According to Genette, a paratext "constitutes a zone not only of transition but also of transaction: a privileged place of a pragmatics and a strategy, of an influence on the public, an influence that ... is at the service of a better reception for the text and a more pertinent reading of it" (2). Even in modern texts, the mere inclusion of paratextual information is significant. As Levy and Mole write, "paratexts can send messages even if you don’t read their text. The presence of a long section of endnotes displays the scholar’s erudition even before you start to read them" (6). Even the examination of Biathanatos displayed on this page could shape how future readers interpret the written text. In a collaborative effort spanning the decades between the initial composition of Biathanatos and its publication in the 1640s, Donne, the publisher Humphrey Moseley, and the unidentified printer would need to anticipate how readers might react to certain paratexts and include only those which are the most persuasive and effective.

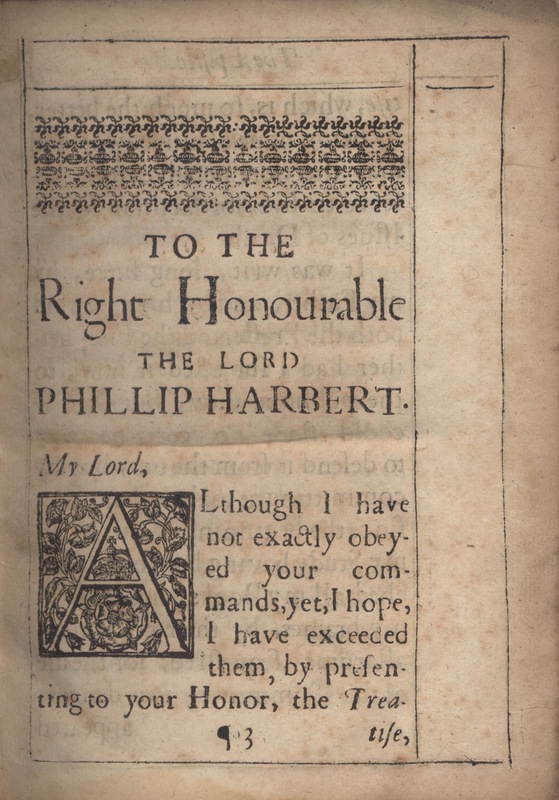

Dedicatory Epistle

Genette's notion of transaction is especially relevant in thinking about the paratextual letter included at the beginning of Biathanatos, which was sent from John Donne’s son to Lord Phillip Harbert (see figures 12 and 19). This letter asks Harbert to support the publication of Biathanatos on the understanding that the book is a "firme and established truth," but publishing this claim extends its influence to a wider audience. In many ways, the dedicatory epistle becomes an open letter to the reader. While it originally sought approval for the publication of the book, the letter is repurposed and becomes a correspondence between the text and its new readers. The letter as a type of paratext emphasizes, with particular clarity, the underlying sense of transaction inherent to all effective paratexts.

The letter also attempts to channel the authority of Harbert, who must have approved the publication, into the book itself. The appeal to authority therefore demonstrates how paratexts can create a "better reception" of the text, as this rhetorical move may have persuaded readers to explore a potentially dangerous book. If the lord approved it, could it be heretical? The issue of authority is also relevant in light of the closing signature on this document. The letter is signed "Io: Donne" (or John Donne), which could give the impression that Donne—the poet and Dean of St. Paul's Cathedral, not his son who bears the same name—penned the letter. How might the audience react if they mistakenly inferred that Donne claimed his work was a firm and established truth? Perhaps more importantly, was the printer aware of the possible confusion and allowing the ambiguity for rhetorical purposes? Even if the reader knew the letter was written by Donne's son, the familial link between the Donnes would have offered its own authority that could encourage readership.

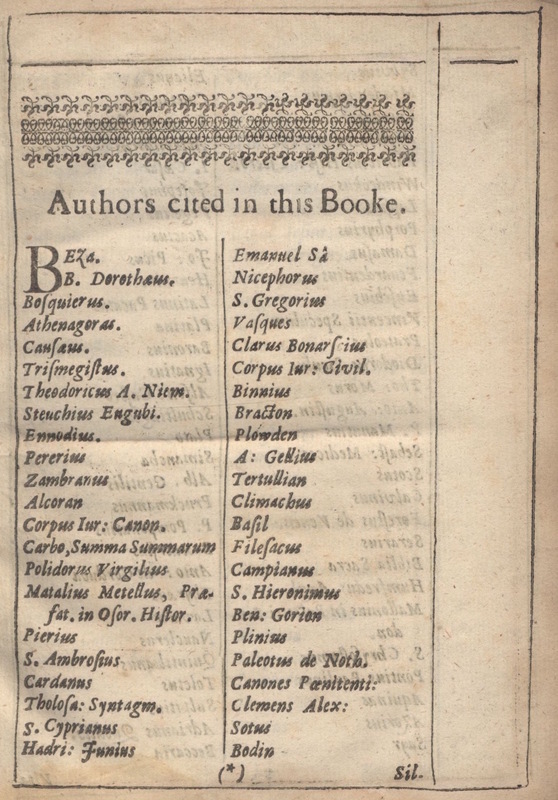

Fig 13. First of four pages listing authors cited in the book.

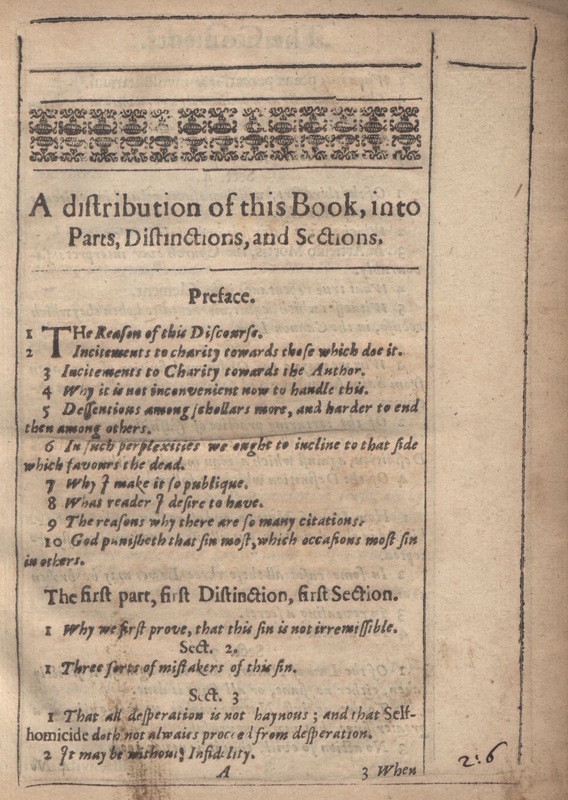

Fig 14. A detailed list of parts, distinctions, and sections.

Citation and Evidence

Continuing the emphasis on legitimacy and authority, the book includes a paratextual list of authors cited in the work (see figure 13). The list spans four pages with double columns and includes 173 names, but it fails to inspire aesthetic attractiveness or engage readers through an explicit argument. Instead, the greatest impact of the list is its length and the sheer quantity of names—which readers may or may not have recognized—that can be used to support Donne's defence of suicide. The list implies that Biathanatos is grounded in strong textual evidence and partakes in a conversation with ancient and contemporary authorities, features that help persuade skeptical readers. This dialogue between writers, despite the fact that Donne died over a decade before its publication, legitimizes his arguments as it situates the work in an established scholarly context. Moreover, this type of list appears in other theological books, indicating that Biathanatos engages with an early modern tradition and style of argumentation.

A Distribution of this Book

The "Distribution" of Biathanatos follows the list of authors and resembles a modern table of contents (see figure 14). This paratext divides the three major parts of the main text into "distinctions" and smaller, numbered "sections." While similar content lists are used to give structure to other early modern books, the high level of detail in Biathanatos demonstrates how Donne carefully and deliberately constructs his arguments. His ability to identify and summarize every feature of the book in great detail, paired with the amount of time it would have taken Donne to annotate these arguments throughout the margins of the full text, indicates that he valued his work. The level of detail allows potential readers to see this value as well. Readers could, moreover, scan through the contents for arguments that were especially appealing and read sections selectively. Although a reader could only understand the full argument by reading the entire book, offering easier ways into the text ensures that the work will not simply overwhelm readers—an important consideration in such a dense and difficult book.

A paratext "constitutes a zone not only of transition but also of transaction: a privileged place of a pragmatics and a strategy, of an influence on the public, an influence that ... is at the service of a better reception for the text and a more pertinent reading of it."

(Genette 2)

ii. Imagining Donne's Imagined Reader

Coterie Culture

It is impossible to know precisely who an author imagined while composing a text—assuming the author was conscious of an intended audience at all—but the study of readership becomes even more difficult when the writer never intended to publish the work. As critic James Kuzner observes, the delay in publication was caused by Donne's persistent fear that readers might misinterpret his work: "Although Donne wrote Biathanatos in the first decade of the seventeenth century, the text was not actually published until the 1640s, more than a decade after its author's death. Donne was exceedingly reluctant to share his text" (76). Donne's hesitance to publish Biathanatos was linked to its controversial subject matter and even a mistrust of the reader, especially as printing the text could have easily attracted accusations of heresy.

To the small group who knew of Biathanatos, Donne actively separated himself from the work by attributing the text to "Jack Donne," the identity often associated with his early erotic poetry, rather than "Dr Donne," his esteemed religious identity that dominated the later half of his life (Kuzner 70). Instead of publishing the work, Donne circulated the manuscript among a trusted coterie—a small group of like-minded individuals—who were interested in interrogating its paradoxical arguments. In addition to a manuscript copy that was sent to "Sr Robert Carre [Ker]" (Sullivan 55), evidence indicates that Henry Goodyer also expressed interest in reading a copy of the text. In a letter to Goodyer, Donne wrote, "it is impossible for me to give you a copy so soon, for it is not of much lesse then 300 pages. If I die, it shall come to you in that fashion that your Letter desires it. If I warm again ... you and I shal speak together of that [a copy of Biathanatos] before it be too late to serve you in that commandment" (qtd. in Sullivan 57-8). Whether or not Donne planned to one day publish Biathanatos, it is clear that he initially intended to share the text with a close group of friends who knew his writing and would not misinterpret the provocative thesis.

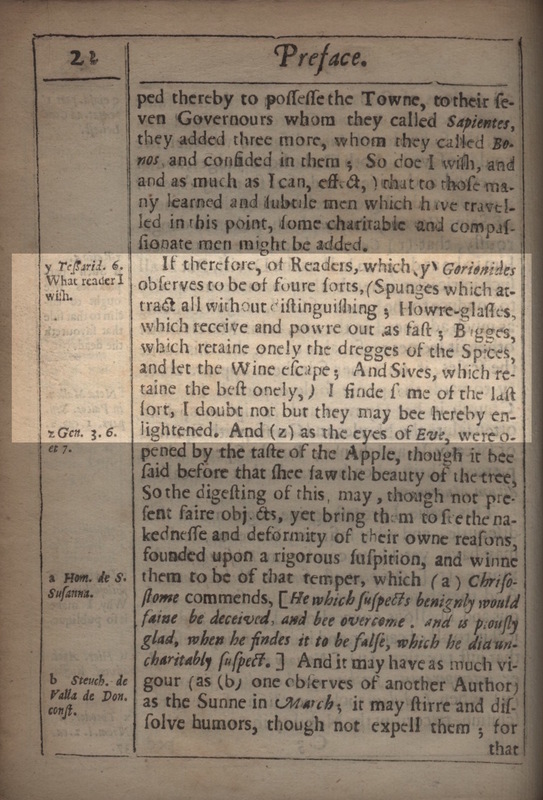

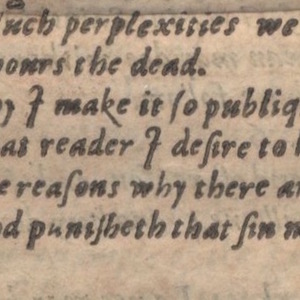

Read like a Sieve

Alongside these specific historical readers who appear in Donne's letters, the book imagines other types of readers who might encounter the text. In the preface of Biathanatos, Donne clearly outlines his ideal reader and contrasts this persona against ineffective or faulty styles of reading. This rhetorical move urges readers to think critically about their own roles and establishes a potential dialogue between reader and writer. Beside a marginal note labelling the section "What reader I wish" (see figure 15), Donne includes the following declaration:

If therefore, of Readers, which (y) Gorionides observes to be of foure sorts, (Spunges which attract all without distinguishing; Howre-glasses, which receive and powre out as fast; Bigges, which retaine onely the dregges of the Spices, and let the Wine escape; And Sives, which retaine the best onely,) I finde some of the last sort, I doubt not but they may bee hereby enlightened. (Biathanatos 22)

The writer compares readers to the various qualities of sponges, hour-glasses, bags, and sieves, stating that the last type of reader will benefit from the work. Donne challenges readers to think about both the true and faulty aspects of Biathanatos and to sieve through the sections for the best arguments.

This passage illuminates the Latin statement on the title page of Biathanatos (see figure 16), which is written as follows: "Non omnia vera esse profiteor. Sed legentium usibus inservire," or "I acknowledge that not all things are true. But that they serve the uses of the people reading it." Donne consistently imagines a readership that is capable of interpreting his arguments in a useful and productive way. Despite his fear that readers might misinterpret the work, Donne remains conscious of the value and enlightenment that can arise from the paradox. It is easy to oversimplify the thesis of this book and suggest it advocates suicide in general, for instance, but Donne would have relied on the ability of his readers to see the nuanced theological arguments at play. The book is a careful meditation on martyrdom and self-homicide for religious purposes—distinctions that make the book a scholarly inquiry rather than a simple treatise aimed to shock audiences.

What argumentative strategies are employed by imagining an ideal way of reading? Donne reinforces his authority by suggesting that any faults in the text are deliberate and therefore serve the purposes of the reader. Moreover, Donne encourages readers to engage actively in the ongoing creation of Biathanatos. While he fills the margins with notes and references, the column on the right of the page also offers a space where readers can inscribe their own critical thoughts and sieve through ideas. The copy at the University of Victoria shows little evidence of reader engagement in the form of handwritten marginalia, but other copies of the book—perhaps even ones that have not survived over time—may contain extensive traces of readers critiquing or agreeing with Donne's arguments. As such, the marginal space offers yet another dialogue between writer and reader that reflects the critical and discerning readership Donne desired.

"Non omnia vera esse profiteor. Sed legentium usibus inservire."

"I acknowledge that not all things are true. But that they serve the uses of the people reading it."

iii. Access to Books

Books were expensive and difficult to acquire in the seventeenth century. Much has been written about the price of books, and the financial questions surrounding Biathanatos are interesting considering the evidence that indicates Donne's son published the book for financial reasons. As Sullivan writes, "the younger Donne's letters ... in presentation copies sent to potential patrons suggest that he needed money" (63). However, the intellectual accessibility of this book is most intriguing. Analyzing the intersection of print and theology, John Pendergast suggests that the printing press enabled greater freedom in the dissemination of texts and ideas: "The printing press ushered in an era in which ideas were channeled into published treatises, the result of which was a breaking of control from centralized authority, i.e. the Catholic Church and its control of textual production, and a simultaneous emphasis on meaning as contained in a single, self-sufficient entity, i.e. the book" (19). England certainly imposed its own constraints on publishing, but it is clear that a greater range of texts were becoming available for those with the skills necessary to read them.

Modern audiences sometimes assume that early modern literacy was negligible, but these assumptions are misguided. Mark Bland offers a useful discussion of literacy in early modern England: "Education was not available as a matter of right in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, but that does not mean that those who were illiterate had no access to, or were not influenced by, the written culture of the time" (84). In other words, the ideas circulating in print were very much a part of the wider cultural conversations of this time. Yet the issue of literacy comes into question with the increased complexity of a book. The "ability to read some things did not mean that all who did read could read everything; a different level of competency was required for a complex book than a broadside ballad or the catechism" (Bland 86). As a complex, dense, and paradoxical work, Donne's Biathanatos would have necessarily challenged even the most advanced readers. Indeed, reading was—and remains—a skill developed over time through the exposure to many different types of texts.

Reading competency aside, different languages foreground themselves as possible barriers to comprehension as well. Almost all of the textual evidence Donne uses to support his arguments is written in Latin, and the book employs Greek on the title page and Spanish at the end of the dedicatory letter. A basic understanding of the four languages used in this book would not be enough, however; readers would need to be well-versed in Latin to understand the full complexity of the dense arguments. Furthermore, if a reader is not familiar with the authors used to defend Donne's arguments—the 173 authors cited in the opening paratexts—how can they know if Donne's arguments are sound or accurately reflect his original sources? These barriers between readers and the book mean that many would not have been equipped with the skills necessary to help them separate true and faulty arguments; as such, many would not have been able to read like sieves.

A Note on the Compositor

It is also worth mentioning that the compositor of this edition mistakenly rotated the Greek Theta in the title of Biathanatos. While this error may have been a simple mistake while setting the type, could it indicate that the compositor did not understand the language or word he committed to print? What does it mean when a text is printed and shared by individuals who might not fully understand the impact of the book?

Fig 19. Beginning of the dedicatory epistle.

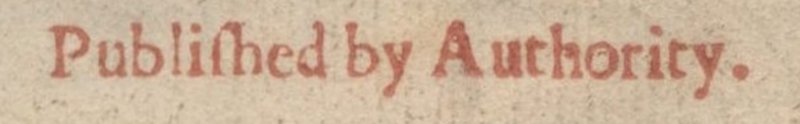

Fig 20. Close up of the title page that states the book was approved for publication.

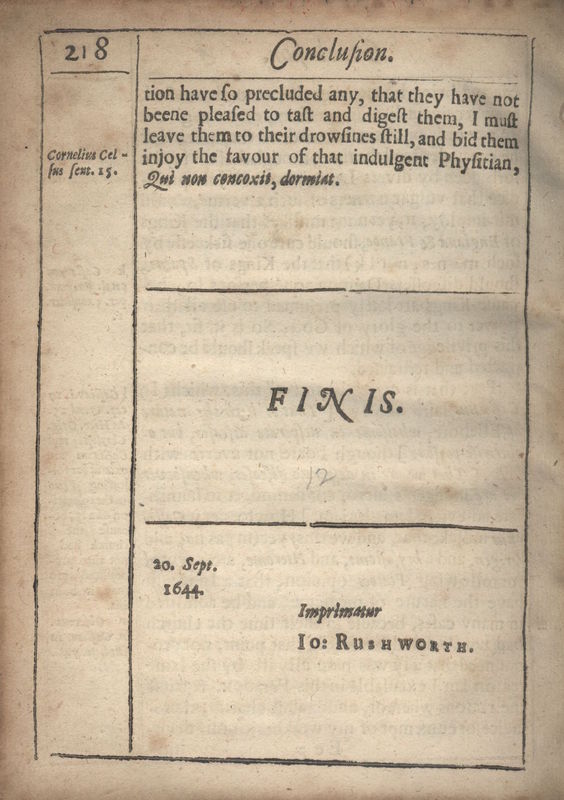

Fig 21. Licensing date printed on the final page of the text.

Death and Dangerous Books

i. Traces of Censorship and Regulation

This copy of Biathanatos is a plain quarto edition with few decorations or embellishments. Compared to expensive and elaborate books produced during the seventeenth century, it is hardly an attractive example. Yet it bears traces of early modern printing practices that speak to issues of censorship and government regulations of printing and publishing. During this period, publishing in England was regulated by the Stationers' Company. They controlled the number of printing presses and printers, managed copyright through the Stationers' Company Register, and started screening books in 1538 to "ensure that they were acceptable for publication" (Levy and Mole 82). Biathanatos was entered into the Stationers' Register on 25 September 1646 (Sullivan 63), but it shows other evidence of regulation as well. The dedicatory letter suggests that books needed approval from higher authorities; similarly, the title page includes the phrase "Published by Authority" in red ink—a colour signaling the importance of such approval—which could only be written on books that were deemed acceptable for print.

At the end of the book, the printer states when the license to print Biathanatos was granted, and the date 20 September 1644 can be seen in figure 21. Examining the complex history of this work's transition from manuscript to print, Sullivan suggests that the license was given on the basis of a manuscript copy Donne's son submitted in 1644. He adds that the delay in printing the book—from the licensing date to the likely printing date of 1647 for both early editions—indicates that Donne struggled to find a printer who would attempt a controversial text that would have also been difficult to print on account of its detailed marginal notes (Sullivan 63). Together, these printing obstacles reveal the complex legal and financial barriers that impacted the printing of early modern books. It is also important to note that this book was printed during the Civil War, when censorship was not as strongly enforced. What types of books were allowed to circulate in early modern England, and why was a controversial text like Biathanatos printed multiple times?

ii. Authority and Legitimacy

Translating a manuscript into print raises questions about the value of books and the cultural sense of authority imbued in printed texts. Since Biathanatos was published after Donne's death, does the author still have control over it? Or does the reader give the text its authority? While manuscript copies could be altered for particular readers, the printed book was reproduced in mass quantities with few variations. A sense of permanence is associated with the printing press: "The physical characteristics of type also introduced limitations as to what could be done with a text once it had been printed. With a written document, insertion, deletion, contraction, correction, and, to some extent, erasure are straightforward activities" (Bland 118). The impression of an unchangeable book implies a firmness in the ideas written in the document. The book becomes a "firm and established truth" in a very literal sense, particularly as the moveable type is "transferred to a galley and locked within a forme" (Bland 118). The language used to describe the printing process suggests that words are secured in both the press and on the page, indicating the definitiveness associated with print.

The sense of timelessness given to the printed book reaffirms the authority of Biathanatos. However, handwriting offers its own benefits that indicate why Donne would only circulate his book in manuscript form during his life. Levy and Mole observe that manuscripts are more intimate and flexible: "In addition to being more accessible, handwriting was a more intimate form of communication, as it was produced directly from the hand of the writer, not mechanically reproduced in identical (or nearly identical) copies" (113). A more intimate form of textual production aligns with Donne's interest in sharing a thoughtful and rigorous examination of theology with his readers. Furthermore, the ability to revise such documents would offer protection for Donne, whose position as the Dean of St. Paul's could have been jeopardized by theologically questionable arguments.

iii. Grim Subjects

Suicide remains a controversial subject today, but it held serious religious consequences in the seventeenth century. Individuals who committed self-homicide occupied liminal spaces: "Their property seized by the state, they were buried face down in a roadway or at a crossroads, somewhere other than a churchyard, somewhere to signify the self-killer's lack of place in the afterlife" (Kuzner 61). This treatment of suicide victims influenced the public view of self-homicide and increased its perceived sinfulness. Concerns about the soul permeated daily life, and the cultural conception of suicide was highly influenced by religious interpretations of the afterlife. Once more, the issue of death was a matter of control and authority. As Kuzner writes, "burial practices reserved for self-killers worked to fix death's meaning publicly and to wrest authority from the dead. A suicide may have been free to opt for voluntary death, but not, coroners sought to make sure, to decide its public significance" (61). Suicide was therefore a difficult subject, and using theological arguments—such as the claim that Christ committed suicide through his martyrdom—would have caused anxieties about faith and the afterlife.

The book was dangerous not only for its discussion of suicide, however. In 1644—the same year the license was granted to print Biathanatos—John Milton published his influential Areopagitica. This speech argues against the use of licensing and censorship, stating that texts should instead circulate freely for the public to decide their value and legitimacy. Early modern thinkers were clearly invested in the right to information. Yet, the lenient censorship practices during the 1640s that allowed Biathanatos to emerge in print demand that readers consider texts critically. Readers must decide how to interpret this paradoxical and often contradictory book: should its arguments be taken at face value, or is Donne prompting readers to challenge his claims? Contrasting its provocative nature, the material book is discreet, affordable, and unembellished. Its overall simplicity adds a further mask over the contents, making it difficult to distinguish among a collection of other books published in the 1640s. The Latin disclaimer on the title page suggests that the answer lies somewhere in between: readers must decide, selectively, which arguments to believe and perpetuate. The danger arises when readers are unequipped to discern the value of arguments; as such, the book seems dangerous not only because it addresses suicide, but because it could easily be misinterpreted by inexperienced readers.

"It was through ink that the printed or manuscript text became a dual witness to the histories of the material process and intellectual content."

(Bland 83)

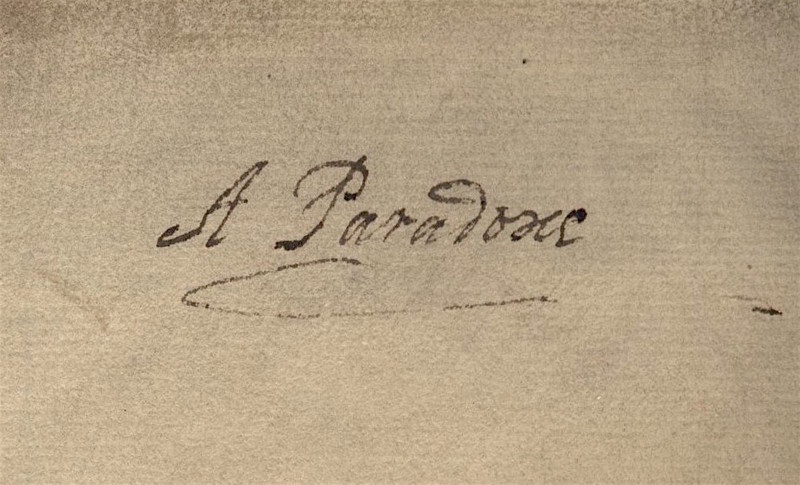

iv. Marginalia

Donne wrote extensive marginalia in the Bodleian manuscript that he gave to Lord Herbert, but the edition of Biathanatos in Special Collections contains only two handwritten notes. The first is a small "2:6" that could refer to a verse number, a section in the book, or a different reference altogether (see the bottom right corner of figure 14). The second marginal note is written on the back of the final page, as shown in figure 23, and reveals how readers might have interpreted the work. Could this note be a reference to the title of the book? The text clearly demonstrates that it was constructed with ideal readers in mind—whether they were imagined by Donne or the printer—but this marginalia inspires much speculation about the readers who actually sieved through the book and formed reactions to the text.

As H. J. Jackson observes, the "writer of marginalia acts on the impulse to stop reading for long enough to record a comment" (82). In a book that includes few other traces left by readers, the deliberate act of inscribing the words "A Paradoxe" on the final page indicates that at least one reader felt an impulse to interact with the text. Rather than simply closing the cover on the book's paradoxical and perhaps faulty arguments, the reader contemplates its contradictory qualities. Jackson further argues that most annotators see themselves as one of two voices who partake in a dialogue. The annotator can talk "either to themselves or to the author" (83), which would complete the conversation that the opening paratexts initiate. Yet, it remains unclear whether the annotator left the note for personal use or, possibly, for other readers in the future.

One cannot know with certainty who wrote this note, but it responds to the careful rhetorical argumentation in both the content and material manifestation of Biathanatos. Moreover, it speaks to an important early period in the history of printing. While the theologically controversial book was designed to appeal to an ideal reader, much of its history and actual readership still remains as elusive as the paradoxes Donne pursued throughout his life.

Related Reading

i. Early Modern Books in Special Collections, University of Victoria

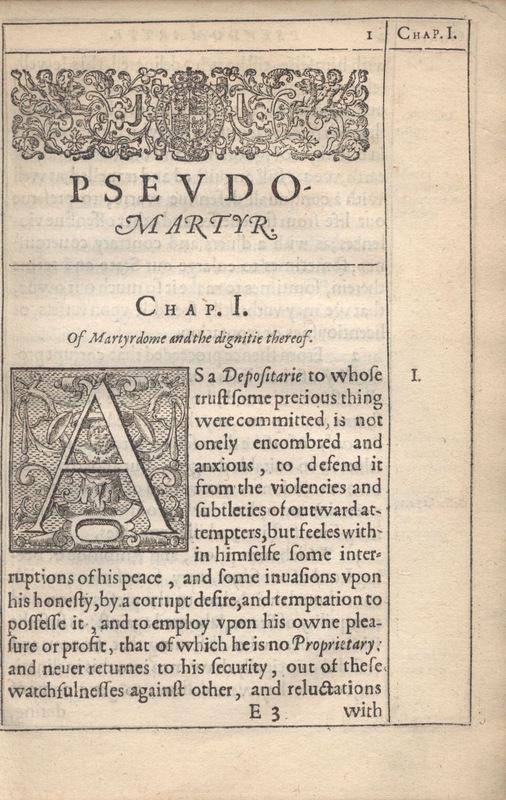

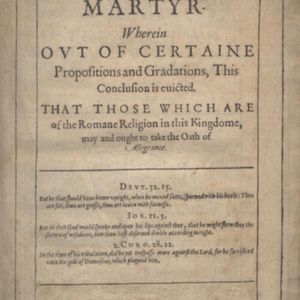

John Donne, Pseudo-Martyr (1610): Written by the same author of Biathanatos and published during his lifetime, this book deals with similar theological issues of death and the afterlife.

William Bridge, The Works of William Bridge (1649): Bridge's collection was published a year after the date attributed to this edition of Biathanatos. The Works also discusses theological topics and similarly includes a numbered list of contents, an address to the reader, and clear marginal lines.

James Shirley, Narcissus, or, The Self-Lover, The Triumph of Beautie, and Poems &c (1646): These works were also published by Humphrey Moseley and printed around the same time as Biathanatos. Special Collections houses several works published by Moseley, and Shirley is one of the many highly influential early modern writers.

The Works of Charles I, as recorded in Reliquiae Sacrae Carolinae (1648): This book bears the same publication date attributed to Biathanatos, discusses martyrdom, and contains a title page that demonstrates red ruling.

ii. Digital Surrogates of Biathanatos

1644 edition: N/A

1648 edition: Google Books

1700 edition: Google Books

iii. Explore Similar Pages in Movable Type

The History of the World (1614)

Collection of Plays Performed at the Theatres-Royal in London and Dublin (1764-1801)

The Present State of Nova Scotia (1787)

The Play of Pericles, Prince of Tyre: Barbarian Press (2010)

iv. Donne's Other Related Work

John Donne, Juvenilia: or Certaine Paradoxes and Problemes (1633)

Acknowledgements

I owe many thanks to my classmates and to Dr. Alison Chapman for their feedback and invaluable guidance throughout the many stages of this research. My work would not be possible without the support of Special Collections as well, and the incredible patience and kindness I received while working with Biathanatos. I would also like to thank Lee Anderson for offering his Greek and Latin translations for this project, and for encouraging a love for Latin that has opened a world of possibilities in my early modern research.

Works Cited

Bell, Maureen. "Mise-en-Page, Illustration, Expressive Form." The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain, edited by John Barnard and D. F. McKenzie, Cambridge UP, 2002, pp. 632-635.

Bland, Mark. A Guide to Early Printed Books and Manuscripts. Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

Chartier, Roger. The Author's Hand and the Printer's Mind. Polity P, 2014.

Donne, John. Biathanatos. Humphrey Moseley, 1648. PR2247 B5 1648. Special Collections, University of Victoria Libraries, Victoria, BC. 2017.

---. Biathanatos. John Dawson, 1644.

---. Biathanatos. London, 1700.

---. Psevdo-Martyr. Walter Burre, 1610. BX1492 D6. Special Collections, University of Victoria Libraries, Victoria, BC. 2017.

Genette, Gérard. Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Translated by Jane E. Lewin, Cambridge UP, 1997.

Jackson, H. J. Marginalia: Readers Writing in Books. Yale UP, 2011.

Kuzner, James. "Donne's Biathanatos and the Public Sphere's Vexing Freedom." ELH, vol. 81, no. 1, Spring 2014, pp. 61-81. doi:10.1353/elh.2014.0002.

Levy, Michelle, and Tom Mole. The Broadview Introduction to Book History. Broadview P, 2017.

Milton, John. Areopagitica. London, 1644.

Pendergast, John. Religion, Allegory, and Literacy in Early Modern England, 1560-1640: The Control of the Word. Ashgate, 2006.

Slights, William. Managing Readers: Printed Marginalia in English Renaissance Books. U of Michigan P, 2001.

Sullivan, Ernest. "The Genesis and Transmission of Donne's Biathanatos." Library: A Quarterly Journal of Bibliography, vol. 31, no. 1, 1976, pp. 52-72. doi:10.1093/library/s5-XXXI.1.52.

Works Consulted

Bland, Mark. "Jonson, Biathanatos and the Interpretation of Manuscript Evidence." Studies in Bibliography, vol. 51, 1998, pp. 154-182. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40372049.

Brayman Hackel, Heidi. Reading Material in Early Modern England: Print, Gender, and Literacy. Cambridge UP, 2005.

Como, David. "Print, Censorship, and Ideological Escalation in the English Civil War." Journal of British Studies, vol. 51, no. 4, October 2012, pp. 820-857. Cambridge Core, doi:10.1086/666848.

Gascoigne, Bamber. How to Identify Prints. Thams and Hudson, 1986.

Hadfield, Andrew, editor. Literature and Censorship in Renaissance England. Palgrave, 2001.

Peacey, Jason. Print and Public Politics in the English Revolution. Cambridge UP, 2013.

Wheale, Nigel. Writing and Society: Literacy, Print and Politics in Britain 1590-1660. Routledge, 1999.

Woodford, Benjamin. "Developments and Debates in English Censorship during the Interregnum." Early Modern Literary Studies, vol. 12, no. 2, 2014, p. 1-21. Literature Online, gateway.proquest.com.ezproxy.library.uvic.ca/openurl?ctx_ver=Z39.88-2003&xri:pqil:res_ver=0.2&res_id=xri:lion&rft_id=xri:lion:ft:criticism:R05122705:0&rft.accountid=14846.

AH/Fall2017