Woman's World, edited by Oscar Wilde (1887-1890)

Woman's World is a late-nineteenth-century women's magazine that represents the changing social status and cultural conception of the woman and the feminine at the time of its publication. Prominently featured are articles and advertisements that showcase the current fashions and other commodities associated with being a "woman" in the nineteenth century.

In November 1887, Oscar Wilde took up his post as editorial head of the magazine Lady's World, and officially changed its name to Woman's World. This shift is a mark of the changing political atmosphere of the late nineteenth century, where the term "woman" was distinguished from "lady": the lady was a lady of the house, a wife and mother first and foremost, while the woman was educated, cultured, and concerned with matters of women's economic and political autonomy. Furthermore, "lady" denoted a certain high-class status, while "woman" remained neutral. It is important to note that traditional notions of femininity were not discarded or forgotten - women were expected to undertake the qualities of the new woman while also maintaining their femininity. This double-bind was captured perfectly by the contents of the magazine: politically-oriented articles and literary contributions are interspersed with fashion articles and advertisements for cosmetics.

In her article, “Oscar Wilde’s The Woman’s World,” Stephanie Green pinpoints the target audience for Woman's World as “an elite but expanding readership of middle and upper class educated women with literary and social credentials” (Green 102), who were just becoming economically independent amidst the changing social climate of education and employment opportunities for women, most of whom were previously only able to work in the home as mothers and homemakers. Woman’s World made literature, political information, and modern fashion trends available to this new class of women for the price of one shilling per month – more expensive than most women’s magazines of the time, but these “New Women” (Green 103) were assumed to have income to spare. In this sense particularly, the innovative (even revolutionary!) nature of Woman’s World becomes apparent: because this demographic was just emerging in the late 1880s, the average New Woman reader did not have their newfound economic independence established enough in order to afford such an expensive magazine every month. It is for this reason, Green argues, that the magazine eventually went out of print in late 1890. Green also hypothesizes that if Woman’s World had been published even five years later, its lasting success would have been all but guaranteed.

My interest in Woman’s World lies squarely with my interest in popular culture products and the way that ephemeral texts such as these reflect larger political and social movements, and demonstrate the nuances of a historical era that is often painted with generalized strokes in our contemporary collective consciousness. Woman’s World was a site of contention and debate for those who had stakes in the question of the New Woman, a medium through which contributors could express their beliefs and respond to one another, and where the readers could create meaning from the different views presented and apply them to their lives. Contributors debated the merits of gender equality and women’s suffrage, amidst the articles regarding that season’s fashions. Each of these types of articles were presented as equally important, and without preamble from Wilde – this is exactly what makes Woman’s World unique. The magazine was a site for contention and debate as well as aesthetic appreciation. It precisely captured what it meant to be a New Woman and created a small “world” for the phenomenon, with each aspect of New Womanhood represented as equally important. While Woman’s World was complicit in enforcing a kind of feminine double bind, as I mentioned previously, it still catered to the women who took joy in certain material aspects of femininity such as fashion and interior decorating. Unlike a considerable amount of feminist-minded media today, Woman’s World does not deride these traditionally feminine pursuits as lesser, or frivolous, or morally inferior; rather, it was in the hands of the reader to make these judgements for herself. In a time where the very idea of the New Woman and the concept of equality for women was lampooned in other mainstream publications, painting these emerging, progressive women as angry, ugly spinsters, I argue that it is a powerful political act to present a world where the New Woman could be both independent and feminine.

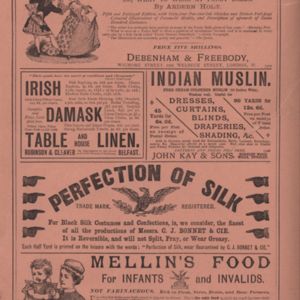

In this exhibit, I will discuss the aspects of Woman’s World that I find represent most clearly the complex, even contradictory message(s) that Wilde and Woman’s World have to offer. First, I discuss Wilde’s role as editor and his contribution to the magazine, looking at the monthly column he was responsible for, “Literary and Other Notes”, and examining some of the rumours surrounding his work ethic and behaviour regarding his post with Cassell and Co. Next, I examine some of the illustrations and other visual additions to the magazine that add to its ability to create an immersive experience for the intended reader, and put forward certain notions of femininity that the reader was meant to emulate. Finally, I include a gallery that showcases the advertisements and some other paratextual material from the second part of Woman’s World, December 1887, and follow that up with a discussion about the importance of these advertisements toward our understanding of the magazine and the possible effect of excluding this paratextual material from the bound Christmas volumes of the magazine.

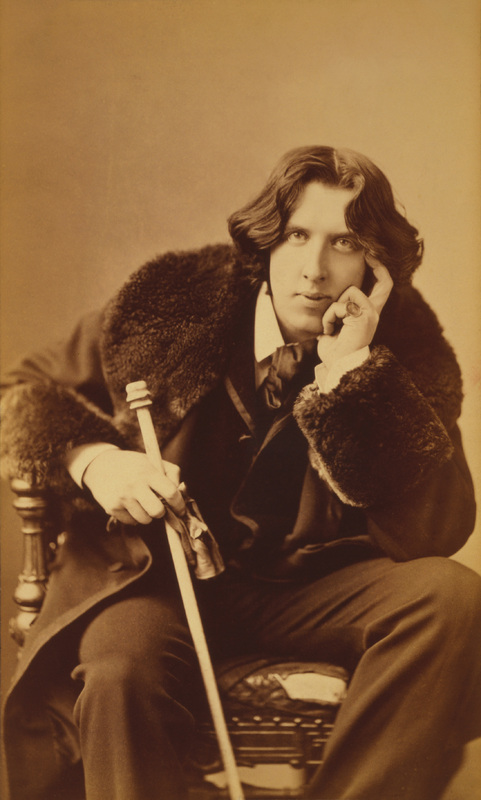

"Oscar Wilde in his favourite coat" - Portrait circa 1882 by Napoleon Sarony

"Literary and Other Notes" - Oscar Wilde's contribution to the December 1887 issue of Woman's World

In her article, "The Woman's World: Oscar Wilde as Editor," Anya Clayworth argues that it was Oscar Wilde's experience in journalism, and the resulting keen understanding of the literary marketplace and public demand, that contributed directly to Wilde's success as a writer in the later years of his career. Prior to his post at Woman's World, Wilde had no experience as an editor; he was a published author and had toured in North America, but his most successful works - The Picture of Dorian Grey and Lady Windermere's Fan most notably - were not published until after his stint at Woman's World. Clayworth argues that Cassell and Co employed Wilde in order to "exploit the novelty of employing a 'celebrity' to edit their magazine" (Clayworth 86). The status of women was rapidly changing in the late nineteenth century, the popular conception of 'woman' or 'lady' was changing, and so was the market that appealed to these "new women" (ibid); Cassell and Co needed to be on top of this changing market in order to remain profitable, and their answer to this was Oscar Wilde. His name was featured prominently on the cover, presumably to attract the audience that would be interested in Wilde's progressive attitudes about women, and "moreover attract contributors who would appeal to this particular kind of reader - contributors such as the novelists Ouida, Olive Schreiner, and 'Violet Fane'" (ibid). Thus, what was previously Lady's World became a medium in which contributors discussed the changing position of women in society, women's education, and (to a certain extent) political and economic autonomy - the new magazine would "deal not merely with what women wear, but with what they think and what they feel" (Wilde, quoted in Clayworth 87).

Wilde's contribution to the magazine was his article "Literary and Other Notes" (later, just "Literary Notes"), where he primarily engaged with authors, and wrote some of his thoughts about newly published books and poetry. The title of the column allowed Wilde some flexibility and a license to be creative with the contents of his writing; his ‘reviews’ of literary pieces are not formally structured and often read more like a conversation between Wilde and the author. Aside from his notes about literature, Wilde also included some gossip from his social circles and London High Society in his column. Interestingly, his section replaced the gossip section in Lady’s World, which was considered to set a trashy tone for the rest of the magazine (Clayworth 93). One can suppose that Wilde’s gossip was excused because it was woven in with more ‘proper’ conversation about literature. Stephanie Green notes that it is through “Literary and Other Notes” that Wilde hones his characteristic style for later writing. His ironic tone and satirical inversion are evident; he also coins a few phrases and epigrams that he later reproduces in his published works.

“Literary and Other Notes” appeared on a semi-regular basis in the magazine - supposedly, there were several months when Wilde felt "unwell" and could not complete his article (Clayworth 94). As the celebrity editor, Wilde was characterized by many as a sort of "lackadaisical genius" (ibid) who dropped into the office for a quick visit before hurrying off to some other engagement. There is, of course, evidence to the contrary here; Wilde seems to have been quite successful at soliciting contributions and developing relationships with writers that would appeal to the audience of the magazine. He knew that his targeted demographic of the New Woman was growing and he knew how to cater to them, and this knowledge of the literary market would serve to help his career once he left Woman’s World. This aspect of Wilde as the businessman and strategist navigating a particular market may arouse suspicion regarding the sincerity of his progressive attitudes. Is it possible that Wilde and Cassell were merely exploiting an emerging consumer group?

Reflecting on Wilde’s career and his writing, I am hesitant to discount his efforts here as merely profit-seeking. While largely within the boundaries of Victorian decency on the surface, Wilde’s writing is often interpreted as sneakily subversive and lends itself easily to queer or feminist readings. He could not fully denounce the society and customs he was navigating within and remain successful, but his work can be read against this normative grain and be understood to be toying with the concepts of the gender binary, and questioning the roles of the masculine and feminine in society. Woman’s World as a magazine, which is ephemeral in nature and therefore not considered to be ‘Literature’, was the perfect site to experiment with these ideas (on both sides, progressive and traditional) and have an ongoing conversation. As an ephemeral cultural object, the magazine as a medium was (and still is) considered to be a disposable object with little social value or cultural weight. However, this particular medium ensured that the ideas, debates, and literature contained within was affordable and accessible to a wide range of readers, who were then given the opportunity to engage with the emerging dialogue.

“Literary and Other Notes,” then, was one of the ways Wilde contributed to this conversation. In this column, he reviews work from female authors – offering the occasional sardonic quip one should expect from Wilde, but largely offering encouragement and constructive criticism to the authors directly. Choosing to use his magazine and his column to uplift the work of women and participate in cultural discussions about the New Woman was a political act, one that justifies a progressive understanding of Wilde’s tenure at Woman’s World and his career as a whole.

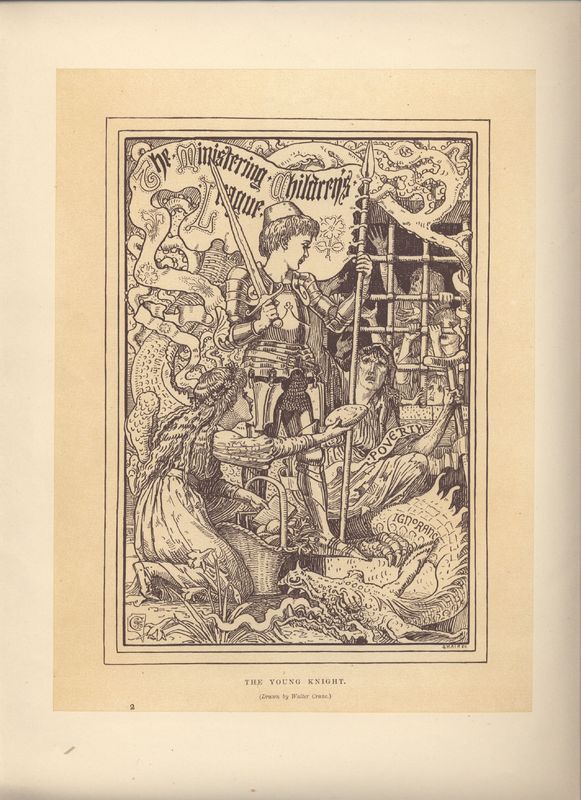

Illustration plate in Woman's World (Dec 1887). Titled "Young Knight", attributed to Walter Crane

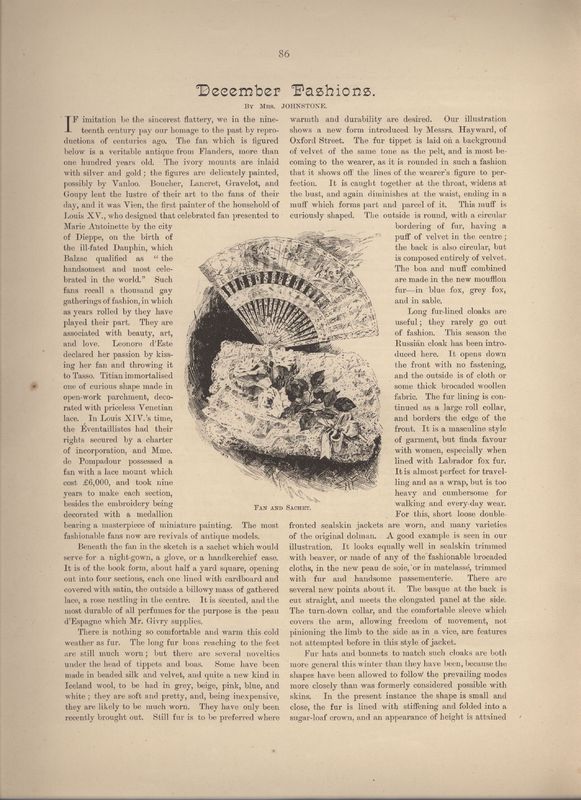

Illustrated first page of the article "December Fashions" in Woman's World (Dec 1887). The article is attributed to "Mrs. Johnstone". The illustration, captioned "Fan and Sachet" is unattributed.

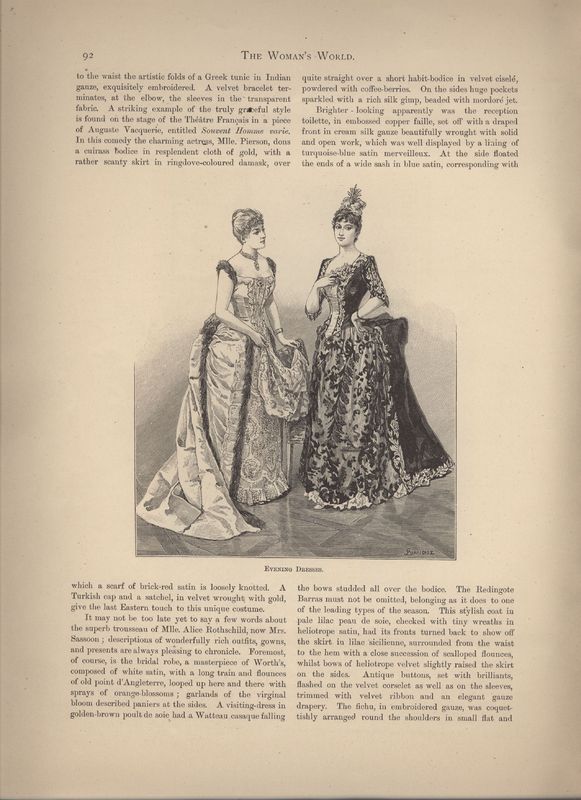

Illustrated page of "December Fashions" in Woman's World (Dec 1887). The illustration, captioned "Evening Dresses" is unattributed.

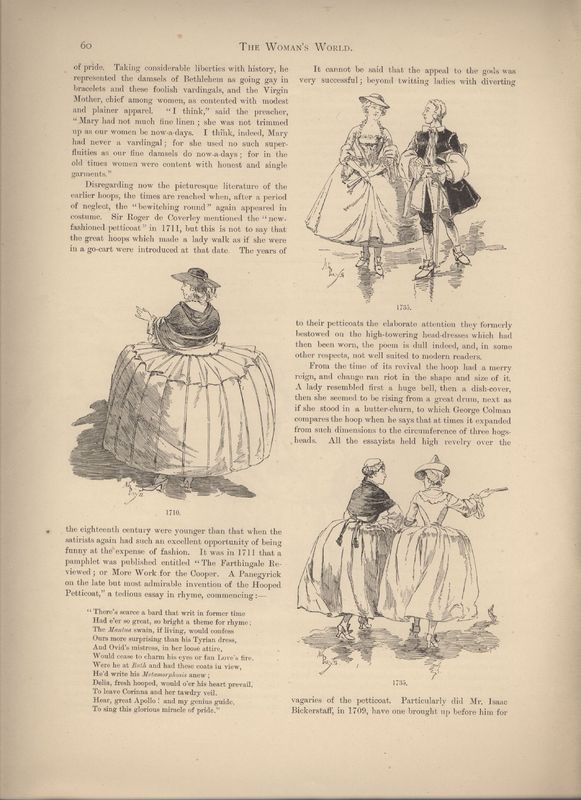

Illustrated page of "A Treatise on Hoops" in Woman's World (Dec 1887). The article is attributed to S. William Beck. The illustrations, captioned "1735", "1710", and "1735" from top to bottom are unattributed.

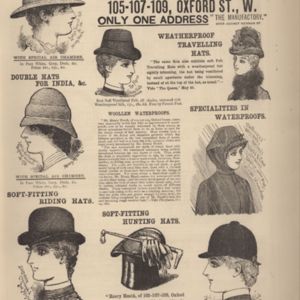

When Wilde took over as editor and sought out more costly contributions to Woman’s World from more well-known authors, he did his best to cut down on illustrations as they were expensive to reproduce in print. However, a significant number of illustrations could not escape Wilde’s editorial veto, and remained. Illustrations in Woman’s World included advertisements as well as artistic renderings of the dresses, accessories, and interior décor described by the magazine’s contributors. Isobel Hurst, in her article, “Ancient and Modern Women in the Woman’s World”, discusses how Woman’s World was associated with aestheticism, through the topics of the articles and their accompanying illustrations, as well as Oscar Wilde, who she describes as “the visible embodiment of aestheticism” (Hurst 45). For many, Wilde represented a type of masculine aestheticism, which notoriously appropriated the domestic sphere and derided female homemakers and ladies-of-the-house as “ignorant amateurs” (ibid) in the traditionally feminine spheres of fashion and interior decoration. Wilde’s Woman’s World, however, rejected that attitude and put forward “a feminized realm of aestheticism in contrast with the [masculine] version exemplified by the Yellow Book” (ibid), which was a magazine in published in London between 1894 and 1897. In all manners of (domestic) aestheticism, the New Women were treated by Woman’s World as the experts.

The assumed reader of Woman’s World was the upper class, educated New Woman of discerning aesthetic taste. Wilde desired a “socially and intellectually elite readership and authors” (Brake, quoted in Hurst 44) but, in order to remain profitable, they needed to appeal to a middle-class readership as well. These middle-class readers could hardly afford the cost of the magazine – this is, ultimately, the reason the magazine went out of print after such a short run – and they also could not afford the expensive dresses and wares being advertised in the articles and illustrations. Scholars of Victorian material culture such as Jennifer Sattaur note that these women of limited financial means would, rather than purchasing a dress shown in Woman’s World, take the magazine to their tailor to recreate the dress, or make the attempt at home – presumably, after purchasing some of the fabric advertised in the front of the magazine. For these women, I assert that the magazine has a different meaning than for the wealthy, upper-class reader. Much like reading Vogue today, Woman’s World put forward an aspirational femininity, which could only be truly obtained with a significant amount of disposable wealth.

Though the New Woman was conceived of as an emerging demographic of newly educated and newly financially independent former Ladies, the New Woman is never depicted within Woman’s World as a working woman. Even in discussions of education and politics, aesthetic is not forgotten. A Woman’s World article titled “The Oxford Ladies College” describes the motivation of female students in seeking an education: “the greater number are attracted by the larger life, the more real education, the manifold interests which life in a community must always afford” (32-33). More attention is paid to how education looks – the social activities, the decoration of libraries and common rooms, and the social weight of being ‘educated’ – than to the career-oriented aspects of education enjoyed by their male classmates.

This cultivated aesthetic is a major part of the prescriptive femininity offered by Woman’s World, which was assumed to be adopted by all its readers, regardless of class. Women had a newfound freedom to pursue their interests outside the home; however, this did not mean that women were exempt from maintaining their traditional femininity. Upper-class women with wealth achieved this new standard much easier than their middle-class counterparts, who were now trying to balance the mandate of New Womanly independence with traditional feminine appearance and behaviour. As a complete cultural object, containing literature, political articles, fashion advice, educational treatises, illustrations, poetry, and advertisements, Woman’s World curates an immersive site of identity formation for the New Woman. From a contemporary, intersectional feminist lens, this text is certainly one muddled with grey area and certain questionable aspects, but for its era it was a progressive leap forward. For example, the reason the magazine grapples with the question of the “New Woman” is because “feminism,” as we define it today, was not a word until approximately 1895 (OED). Woman’s World encouraged perfection from its audience, and it is in these very early texts that the contemporary feminist can see roots of the ‘Superwoman’ myth perpetuated by the Girl Power of the late twentieth century – the woman who is a great mother, beautiful wife, and an ambitious career woman.

To view the full images in the Gallery, click once on the image, then again on the image in the box that pops up with the metadata.

Woman's World was published at Christmastime as an illustrated volume, bound in hardcover and intended to be purchased as a keepsake, with the contents of that year's issues all bound together without any "paratextual" material such as advertisements or individual tables of contents. The Special Collections library at the University of Victoria holds both the bound volumes and the monthly parts of Woman's World published during Wilde's tenure as editor - interestingly, they are held under the same call number and not completely differentiated in the library catalogue. If I had not known to go looking for the monthly parts, I would have retrieved the illustrated volumes from the archive and this project would have looked much different. The bound volumes have, predictably, stood the test of time better than the monthly parts, which are bound with twine and glue. Therefore, it may be fair to assume that more libraries and institutions will have copies of the bound yearly volumes of Woman’s World, and fewer archives have preserved sets of the monthly parts of the magazine. What effect does this have on our understanding of Woman’s World?

Cassell and Co. likely saw the Christmas market as highly lucrative for their business; for example, an illustrated volume could be sold for anywhere from nine shillings to twenty shillings (as Cassell and Co advertised in the front matter of this part of the magazine, demonstrated in the gallery above), and it is likely that many readers of the magazine would like to purchase the keepsake volumes to preserve, while the monthly parts were disposable ephemera. This simple fact of the longevity of the Christmas volume, I argue, changes our contemporary perception of Woman’s World. Stripped of its paratextual material, namely the print advertisements and inserts, the monthly contents are grouped together away from the advertisements that contextualized the articles and illustrations as part of the commodity of the magazine. The advertisements emphasize the mixed messages and double bind encouraged by Woman’s World, in which an article titled “The Fallacy of the Superiority of Man” is prefaced with pages of advertisements for household cleaners and textile patterns. The removal of this paratext in order to sell Woman’s World as literature or a keepsake removes the dozens of advertisements that showcased female-targeted commodities, cementing the women’s magazine as a site that encouraged femininity and conformity to feminine gender roles such as homemaking. Without these advertisements, Woman’s World appears more progressive to the contemporary researcher investigating the bound volumes. Being that they are indistinguishable in the library catalogue, the bound volumes may be considered to be a substitute or replacement for the monthly parts, and I strongly argue that they are not. The keepsake volumes are ‘timeless,’ in a way, and lack the cultural context that adds a necessary nuance to our contemporary understanding of Woman’s World.

In his monograph, Reading Popular Culture in Victorian Print: “Belgravia” and Sensationalism, Alberto Gabriele investigates the experience of the Victorian reader in regards to another monthly magazine, Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Belgravia. His analysis complements my understanding of Woman’s World as an immersive experience, and argues that although magazines are essentially fragmentary and made up of separate contributed pieces, there is a sense of “symbolic cohesiveness that brings together the mosaic of perspectives and disparate stimuli that constitute the magazine” (Gabriele 35), and leads to a nuanced understanding of a larger culture – such as that of the New Woman, when one reads Woman’s World. It is understood that not all Victorian readers would have read “a single issue as a complete unit” (Gabriele 42), as one would read a book, but there is a kind of “montage effect” (ibid) produced when an individual casually reads a monthly part of a magazine such as Woman’s World or Belgravia. Contained within these parts are stories, articles, poetry, illustrations, and advertisements, each of which serve to produce a different aspect of the "world" created by the magazine. The advertisements support the aspects of Woman’s World that can be considered traditional or less-than-progressive, but they add to the conception of Woman’s World as an immersive, aspirational experience for the New Women it targeted. Not only did the articles within showcase and encourage a certain type of well-dressed, well-educated femininity, the advertisements showed women how and where to purchase the commodities that would allow them to achieve this aspiration.

Bibliography and Works Cited

Clayworth, Anya. "'The Woman's World': Oscar Wilde as Editor." Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 30, no. 2, 1997, pp. 84-101.

"Feminism." OED Online. Oxford UP, 2012, www.oed.com.

Gabriele, Alberto. Reading Popular Culture in Victorian Print: "Belgravia" and Sensationalism. Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

Green, Stephanie. "Oscar Wilde's 'The Woman's World'." Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 30, no. 2, 1997, pp. 102-120.

Holland, Merlin and Rupert Hart-Davis, eds. The Complete Letters of Oscar Wilde. Henry Holt, 2000.

Hurst, Isobel. "Ancient and Modern Women in the Woman's World." Victorian Studies, vol. 25, no. 1, 2009, pp. 42-51.

Sattaur, Jennifer. "Thinking Objectively: An Overview of 'Thing Theory' in Victorian Studies." Victorian Literature and Culture, vol. 40, 2012, pp. 347-357.

Woman's World, vol. 1, no. 2. Edited by Oscar Wilde. Cassell and Co, London, December 1897. University of Victoria Libraries Special Collections, PR5820 W6.

Kira B/Fall 2016