The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath (1963)

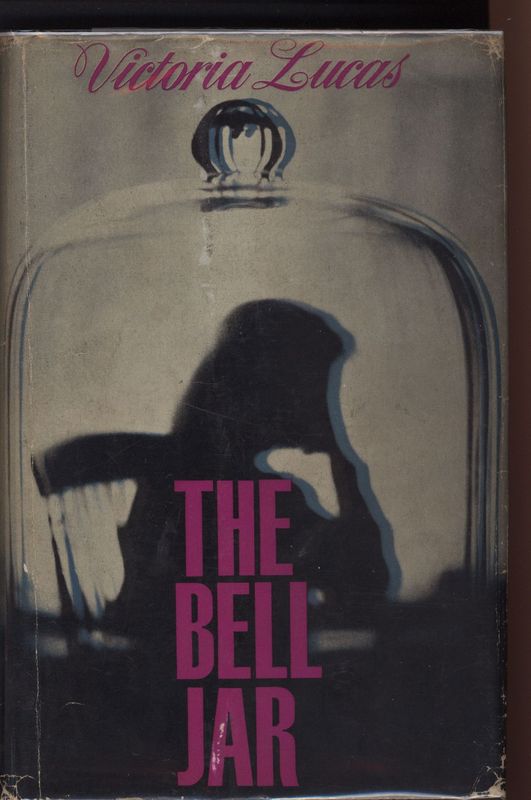

Cover of the first edition of The Bell Jar, written by Sylvia Plath under the pseudonym of Victoria Lucas. Published by Heinemann in 1963, wrapper designed by Thomas Simmonds.

Introduction

Having already accrued renown as a poet, Sylvia Plath chose to publish her first novel, The Bell Jar, under a pseudonym for many reasons. Due to the book's highly personal and semi-autobiographical nature, Plath did not wish to be associated with the text and was concerned with hurting people mentioned in the book. Plath was also concerned about how her mother would react to the novel, which detailed her suicidal ideation, sexual relationships, and other thoughts and actions of a confessional nature. Consequently, Plath requested that the book never be published in America, as many of the characters referenced were real people who she met during her internship in New York City. Furthermore, if the novel was received poorly, then Plath did not want those poor reviews to colour the public’s perception of her poetry. Consequently, under the pseudonym of Victoria Lucas (a rejected name for the novel’s protagonist), The Bell Jar was published in 1963.

“The Bell Jar is an unusual book as it has three different first editions: two in England and one in the United States. The first edition is the Heinemann edition,” says Plath scholar Peter K. Steinberg in his introduction to the novel, located at his website. This first edition was published pseudonymously in 1963. Following Plath’s death, Ted Hughes, who became the executer of Plath’s estate, gave Faber permission to publish The Bell Jar in 1966 under Plath’s real name. The first American edition was published by Harper & Row on 14 April 1972 due to high demand and, according to Steinberg, fear of piracy.

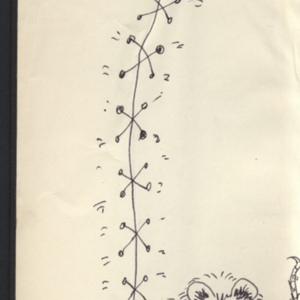

Of all of these editions, the Heinemann edition carries the distinction of being the only one approved by Plath herself. The Faber edition is almost identical, save for the omission of a dedication. Harper & Row took some editorial liberties which I will further address later. This particular copy of the Heinemann edition, however, carries further distinction. This copy, now available in the University of Victoria Library’s Special Collections, was given by Ted Hughes to Nicholas Hughes as a gift. Following Nicholas Hughes’s death in 2009, the copy was passed on to Frieda Hughes. Not only is her name written on the title page, but her drawings cover the flyleaves of the novel. According to the Bookseller’s description as it is printed in the Uvic Library Catalogue, “Frieda, an artist… ‘mended’ the wear to the cover and early pages in a series of playful sketches. With two signed letters of provenance from Frieda (in her hand) as well as her initials to the sketches and her signature on the title page. The front board has a large crease running lengthwise, which runs onto the first couple of leaves. It is this damage that Frieda has ‘mended’ with her art, first drawing a zipper up the front paste-daon, then stitching up the adjacent leaf. A small mouse finishes the stitching on the verso of the front fly-leaf and a crocodile sits on the half-title and on the verso over a small tear in the leaf." This copy is a requent acquisition of the University of Victoria Library's Special Collections section, and has not previously been the subject of scholarly attention.

The interactions between Plath’s children and her first novel form an interesting contrast to Plath’s relationship with her own mother. Plath did not want The Bell Jar published in America or under her own name because she did not want her mother to read it. Still, Ted Hughes had no objection to his own children reading the novel in its entirety. This reveals one of Plath’s most pervasive points of appeal: her accessibility. If the vulnerability displayed is The Bell Jar is not satisfactory to the modern reader, then they can turn to her unabridged journals, which are almost entirely published. Many of her letters are publicly available, and some correspondence between Plath and Hughes (description available here) are also available at the University of Victoria Libarary’s Special Collections.

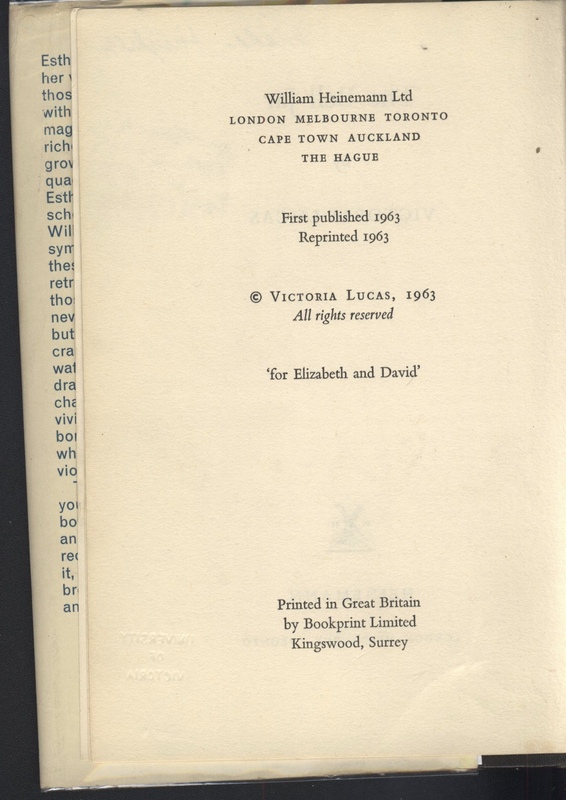

The dedication of the Heinemann 1963 first edition of The Bell Jar.

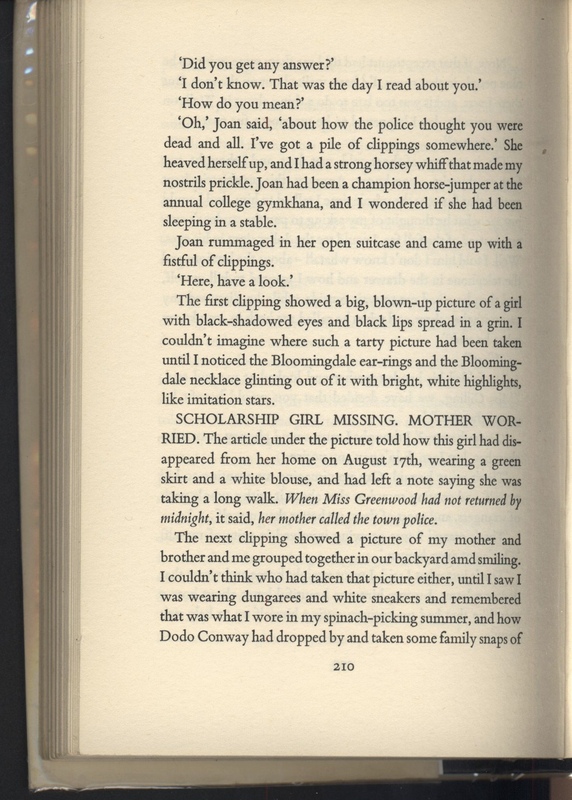

Page 210 of the 1936 Heinemann first edition copy of The Bell Jar, featuring a typographical error.

Page 58 of the 1963 Heinemann first edition of The Bell Jar, featuring Plath's unaltered version of Esther Greenwood's musings on Buddy Willard.

Page 48 of the 1963 Heinemann first edition of The Bell Jar, featuring the nurse's unaltered accent.

Textual Variations

In his article “Textual Variations in The Bell Jar Publications,” leading Plath scholar Peter K. Steinberg exhaustively chronicles every issue of textual variance between the British and American editions of The Bell Jar. There is little variation between the two British editions of the Bell Jar, except that “the first Faber edition lacks the dedication ‘For Elizabeth and David;’ later editions and reprinting restored the author’s dedication” (107).

Up until a 1966 reprint, every Heinemenn and Faber edition of The Bell Jar shared the same typographical error in Chapter 16. When Esther is presented with clippings concerning her disappearance, Esther notes that “The next clipping showed a picture of my mother and brother and me grouped together in our backyard amd smiling” (1963, 210). Though this correction was obviously not approved by Sylvia Plath, it seems easy to extrapolate that she would have been fine with it, given that it is clearly a purely typographical error. Many of the alterations to which The Bell Jar would later be subjected, however, were significantly more drastic. When The Bell Jar was republished in America, Harper & Row took much greater liberties in altering the work which Sylvia Plath had produced and approved.

Naturally, upon its publication in the United States, British spellings were converted to their American counterparts (i.e. colour became color) and double-quotes were used for dialogue (Steinberg 113). Still, Harper & Row made revisions that went well beyond simply Americanizing the prose. The most notable example of this shows up in Chapter 5. In the original Plath-approved Heinemann edition, Esther narrates, “I thought of Buddy Willard lying even lonelier and weaker than I was up in that sanitorium” (1963, 58). In contrast, the 1971 edition reads, “I thought I was up in that sanatorium” (61). Steinberg notes the impact that this alteration has on the portrayal of Esther’s character, pointing out that “The deleted phrase, ‘of Buddy Willard lying even lonelier and weaker than’ makes Esther Greenwood’s compassion for and comparison to Buddy Willard’s situation non-existant, proffering an image of selfish preoccupation to Greenwood which was not Plath’s intent” (133). Steinberg further laments that “in the most recent printings of the book, the excised phrase has not been restored” (133). Different generations and countries often react to differently to literary characters simply because values vary between generations and countries. In the case of The Bell Jar, however, slight differences in the texts aid this disparity.

Another instance of textual variation occurs in Chapter Four. In the Heinemann version, a hotel nurse gives Esther “a ninjection” in an attempt to remedy her ptomaine poisoning. Harper & Row elected to relieve this nurse of her New York accent, despite the fact that it was clearly an intentional choice on Plath’s part. In an early draft of the novel, Plath had typed “an injection,” but she crossed out the “n” in “an” and moved it to the beginning of injection, producing the word “ninjection” (Steinberg 134). Steinberg notes that the subway employee in Boston retains his accent in all texts of The Bell Jar, telling Esther that Deer Island Prison is on “a niland” (1963, 157; 1971, 166; 1996, 166).

Editorial decisions such as these highlight the complex dynamic between authors and editors. Speculation concerning authorial intent is always a sketchy business, and it becomes even more so when an author is no longer alive to voice their intent. Still, it is hard to know where to draw the line when it comes to editing. Few would argue that it was wrong of Faber to correct the blatant typographical error in the word “amd.” Even the conversion from British spelling to American spelling is unlikely to raise eyebrows. In changing the thoughts of the narrator, however, publishers risk altering the integrity of the book infringing on the author's role.

Frieda's Drawings

Though this book is special in that it is a first edition pseudonymous copy of The Bell Jar, this particular copy is unique due to its ownership history. The marks of this history are evident within the book itself. Frieda Hughes’s charming drawings along the inside cover, flyleaf, and title page indicate her ownership of the copy just as much as her signature in the title page. The zipper along the inside cover is simple enough, but suggests many possible interpretations. A zipper mimics the way that you can open and close a book to peer inside at will. Zippers also suggest coming together, which could be taken in countless different ways (Frieda and Sylvia coming together, for example). Along the first side of the flyleaf, a drawing of lace-up stitching is shown to continue along the next side of the page, where it is being completed by a mouse. Along the title page, there is a tear on the side, which forms the open mouth of what the bookseller describes as a crocodile (though I find it more closely resembles a dragon due to the overexaggeration of the teeth and spikes along the back of its neck). As the bookseller observes, these drawings are dependent on the wear already present in the book. They serve to embellish them, as is the case with the zipper, or to utilize them to artistic effect, as is the case with the crocodile/dragon. Though the drawings are done by a skilled artist, they maintain a simplicity and whimsical charm. All feature Frieda Hughes’s initials.

Naturally, these drawings can easily be classified as marginalia. With the digitization of many literary works, the value of marginalia came to the forefront of academic discussion. Scholars such as Andrew Stauffer have dedicated extensive amounts of time and research to digitizing and thereby preserving marginalia along with the text to which it is attached, creating Book Traces, an extensive online database located here. I find these instances of marginalia to be particularly good candidates for digitization given their creator’s attachment to the author of the text. Though these marks easily qualify as marginalia, they could also be considered under a different classification.

Frieda Hughes has many illustration credits to her name, being an accomplished painter who has illustrated many of her own poetic works. Though the sketches left in this copy of The Bell Jar are a far cry from the intricate oil paintings published in conjunction with her own poetic works, Frieda Hughes’s drawings could be classified as illustrations of this work. Hughes has also published several children’s books of her own, though with only one exception (The Meal a Mile Long), they have been illustrated by someone else. The simplicity and whimsy of the drawings may seem more at home in a children’s or young adult book, because of their content just as much as their style. The mouse lacing up the flyleaf is reminiscent of a mouse lacing up a princess’s dress in a fairy tale; the criss-cross pattern of the laces mimics the bodice of a dress, and the laces are tied in a neat bow at the bottom. The fairy tale theme is further maintained by the presence of (what I maintain to be) a dragon on the title page.

These drawings suggest many interpretations. Are they simple and childish because Frieda will always relate to her mother’s work as a child? Is she mending the wear around her mother’s work just as she and her family have tried to posthumously “mend” Plath’s reputation? Does the diminutive stature of the mouse attempting to mend the flyleaf represent how small Frieda feels in relation to her mother’s colossal legacy? Does their fairy tale theme represent the way Esther functions in the text – a princess trying to escape the jaws of her mental illness? Does the open mouth of the dragon represent the book’s ability to swallow the reader? On the one hand, only Frieda knows what she meant by those drawings, and she has not given any interviews on the subject. On the other hand, interpretation need not necessarily end with the author’s (or illustrator’s) intent. The degree of interpretational claim on Plath’s work has been the subject of debate, largely between Plath scholars and Plath’s surviving family.

The cover of the 2013 Faber & Faber 50th Anniversary Edition of The Bell Jar, designed by Richard Skinner.

"Their Sylvia Suicide Doll..."

As a literary figure, Plath’s image has been blown up and distorted in countless ways. In a sense, this seems natural; Plath is a literary voyeur’s dream. Her adolescent struggles and tumultuous adulthood are completely laid out in her published journals. Even without her journals and letters, her novel and poetry are often semiautobiographical. Any reader with sufficient time and curiosity could easily get the sense that they know Plath intimately, and that can give people a sense of ownership over her legacy. Then, of course, many people survive Plath who actually did know her intimately, and they often seek to control or correct her reputation. Scholars have often run into problems with executors of Plath’s estate. In the preface to The Haunting of Sylvia Plath, Jacqueline Rose gives voice to this struggle. While writing the book and corresponding with the Hughes’s, the book was called “evil. Its publisher was told it would not appear” (xi). In fact, Rose was told by Ted Hughes that her “analysis would be damaging for Plath’s (now adult) children and that speculation of the kind I was seen as engaging in about Sylvia Plath’s sexual identity would in some countries be ‘grounds for homicide’” (xi).

Of course any degree of speculation can be made about the motives behind such censorship. Maybe, just as Frieda’s drawings cover up and seek to mend the damaged pages of The Bell Jar, Ted Hughes is trying to mend the broken perception of Sylvia’s reputation. While this creates a frustrating struggle for Plath scholars, Hughes’s outrage could be easily justified by they way that Sylvia Plath has been mangled as a cultural icon. For example, a recent cover of a 50th Anniversary edition of The Bell Jar drew criticism for portraying the book as trite “chick lit,” which many perceived as an insult to Plath’s legacy. Articles (all of which are hyperlinked) sprang up in The Guardian, The Telegraph, Independent, The Poetry Foundation, Huffington Post, and BBC America reporting on the outrage following the unveiling of the cover.

Frieda herself entered this cultural fray upon the release of the BBC’s film version of The Bell Jar (Sylvia, 2003), starring Gwyneth Paltrow. Furious with this portrayal of the darkest period of her life, Frieda penned a poem, “My Mother.” Laced with allusions to Plath’s renowned poem, “Lady Lazarus,” Hughes condemns the voyeurism of people wanting to watch her mother orphan her as a form of entertainment, saying “They are killing her again. / She said she did it / One year in every ten, / But they do it annually, or weekly, / Some / even do it daily, / Carrying her death around in their heads / And practising it.” She concludes by calling her mother “Their Sylvia Suicide Doll / who will walk and talk / And die at will, / And die, and die / And forever be dying.”

While swirling chaos, similar to these raging cultural debates of authorship and portrayal, is frequently present in The Bell Jar, the title itself offers a glimpse into where the book stands in relation to that chaos. A bell jar is a scientific apparatus which is often used to create a vacuum. It is usually a jar shaped like a bell. “To the person in the bell jar,” writes Plath, “blank and stopped as a dead baby, the world itself is the bad dream” (Plath 237, 2006). For the most part, this metaphor is used negatively, but I believe that by appropriating it with a more optimistic outlook, we can arrive at a method of reading and interpreting this work. In a sense, this novel is separate from Plath’s other works simply by being pseudonymous. Plath wanted this book to be read apart from her, even if she did not entirely know what that would entail. But by taking The Bell Jar apart from everything else – apart from her poetry, her journals, her family, her tragic suicide, etc. – and putting it in its own bell jar, perhaps we can get closer to reading this book as Plath would have us read it.

Works Cited

“The Bell Jar by Victoria Lucas.” University of Victoria Library Catalogue.

voyager.library.uvic.ca/vwebv/holdingsInfo?bibId=3528226. Accessed 6

December 2016.

Grocott, Kirsty. “The Bell Jar’s New Cover is Just Perfect: No Chick-Lit in Sight.” The

Telegraph. 7 February 2013.

Hechinger, Paul. “Cover Story: Bell Jar Reprint Artwork Generates Furor - and

Parodies.” February 2013.

Hughes, Frieda. The Meal a Mile Long. Simon and Schuster, 1989.

Hughes, Frieda. “My Mother.” The Stonepicker and the Book of Mirrors. HarperCollins,

2009.

“New Book Cover For Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar Stirs Sexism Debate.” The Huffington

Post. 6 April 2013.

Plath, Sylvia. “Lady Lazarus.” Ariel. HarperPerennial, 2004, pp. 14-17.

Plath, Sylvia. The Bell Jar. Heinemann, 1963.

Plath, Sylvia. The Bell Jar. HarperCollins, 2006.

Plath, Sylvia. The Bell Jar. Faber & Faber, 2013.

Rose, Jacqueline. The Haunting of Sylvia Plath. Harvard University Press, 1992.

Staff, Harriet. “Misguided Cover for Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar Inspires Parodies.” The

Poetry Foundation. 4 February 2013.

Stauffer, Andrew. Book Traces. April 2014, booktraces.org. Accessed 6 December

2016.

Steinberg, Peter K. “The Bell Jar.” A Celebration This Is. Sylviaplath.info. Accessed 6

December 2016.

Steinberg, Peter K. “Textual Variations in The Bell Jar Publications.” Plath Profiles, vol. 5,

2012.

Sylvia. Directed by Christine Jeffs, starring Gwyneth Paltrow. BBC, 2003.

Topping, Alexandra. “The Bell Jar’s New Cover Derided for Branding Sylvia Plath Novel

as Chick Lit.” The Guardian. 1 February 2013.

Usborne, Simon. “50th Anniversary Edition of The Bell Jar Sparks Anger for

Repackaging it as ‘Chick Lit.’” Independent. 1 February 2013.

A.E.W., 6 February 2017.