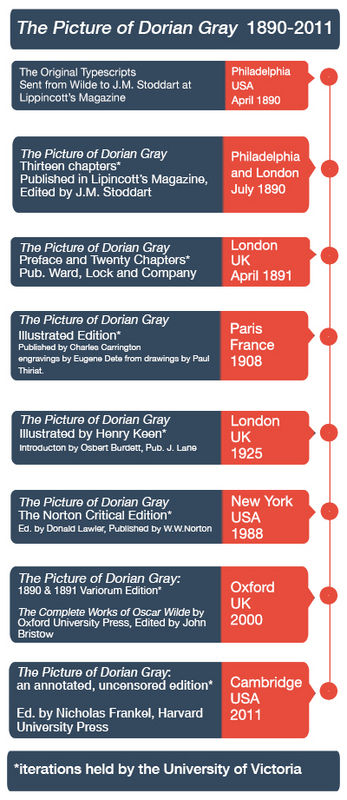

Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890 - 2011)

"It is a tale spawned from the leprous literature of the French decadents — a poisonous book, the atmosphere of which is heavy with the mephitic odours of moral and spiritual putrefaction..." (cited Frankel 6)

- Review of Dorian Gray in the Daily Chronicle, July 1890.

"Wilde in New York" Portrait by Napoleon Sarony (1882) - This same photoshoot with Sarony was the subject of a landmark copyright case at the U.S. supreme court in 1884. (Frankel 173)

Introduction

"The Puzzle is that a young man of decent parts...should put his name (such as it is) to so stupid and vulgar a piece of work." (cited Frankel 6)

- St. James Gazette 5th July 1890

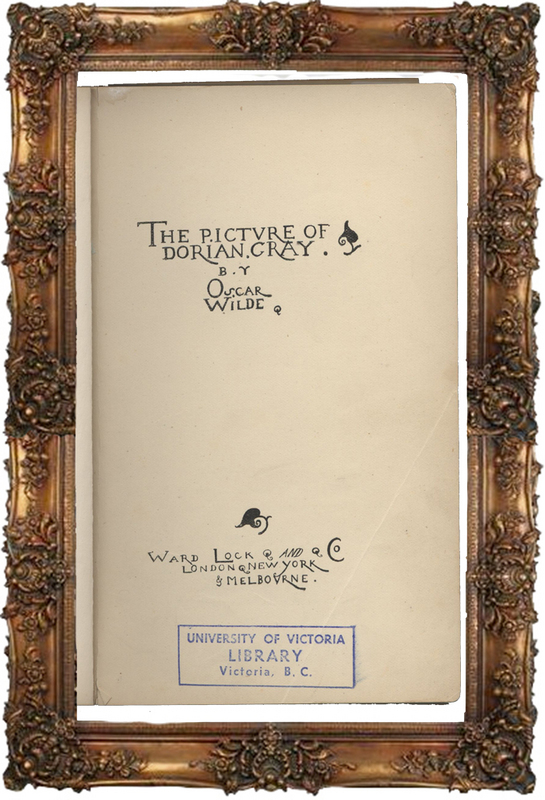

The Picture of Dorian Gray was published simultaneously on both sides of the Atlantic in 1890, appearing as a thirteen chapter edition in the July issue of Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine by J.B. Lippincott Company of Philadelphia, printed in the United States by Lippincott's and in the United Kingdom by Ward, Lock & Co.of London (Frankel 4). The publication of Wilde's only novel came just five years prior to his incarceration for “gross indecency” and ten years before his untimely demise whilst exiled in a Parisian hotel room (Frankel 3).

it was met with critical hysteria, questioning Wilde's morality. The Christian Leader argued that it subtlety reflected the "paganism" which had "been staining the latter years of the Victorian epoch" (Mason 137-138), and the Scots Observer declared it suitable for "‘for none but outlawed noblemen and perverted telegraph boys" (Mckenna 187).

This exhibit will engage with selected iterations of The Picture of Dorian Gray. Most notably the Lippincott's Magazine edition, published in 1890; the 1891 book version, edited by Wilde; and The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition, published in 2011 and edited by Nicholas Frankel.

I engage with the changes to the narrative between 1890 and 1891, as well as analysing in some depth the significance of the advertisements surrounding Wilde's tale in Lippincott's. To what extent do these ephemeral additions infiltrate The Picture of Dorian Gray?

Did Wilde ever maintain control of his art?

Who authored The Picture of Dorian Gray?

The Picture of Dorian Gray, Published in Lippincott's Magazine July 1890

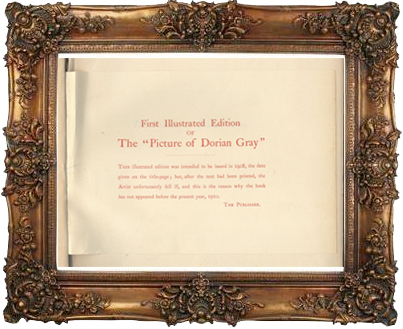

Insert in The Picture of Dorian Gray (1908) this tipped in note from the publisher explains that the volume was intended to be published in 1908, thus explaining the date on the title page, however after the text had been printed the artist fell ill and the book wasn't issued until 1910

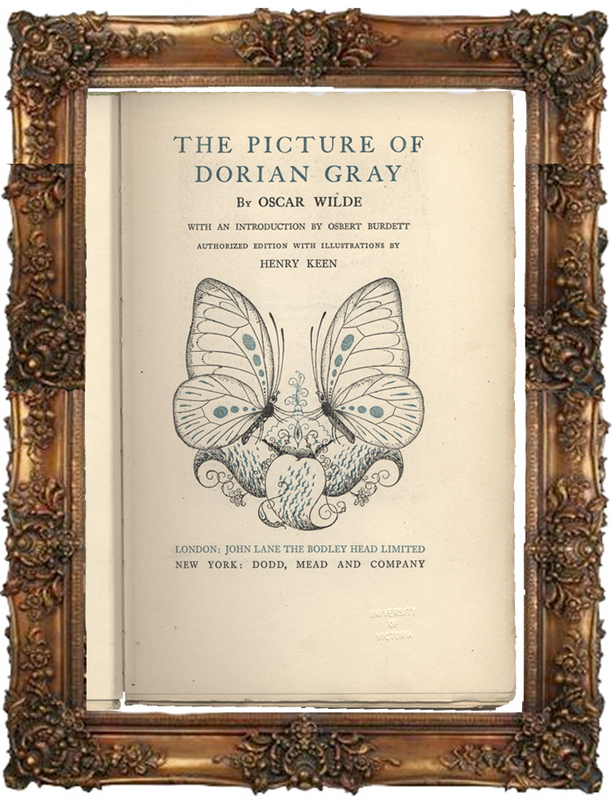

Title Page to The Picture of Dorian Gray (1925). This edition comes with illustrations by Henry Keen, including twelve internal plates and embellishments to the cover.

Title Page to The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition, Edited by Nicholas Frankel, Harvard UP, (2011)

Textual Variants

"A poet can survive everything but a misprint" (cited Pearson 111)

Oscar Wilde, "The Children of the Poets," from a review in the Pall Mall Gazette October 1886.

On the 30th of August 1889 Wilde, alongside his contemporaries Sir.Arthur Conan Doyle and T.P.Gill, met with Lippincott's editor J.M. Stoddart at the Langham hotel on Regent Street in London (Wilde and Hart-Davis 95) to discuss the commissioning of short novels for publication in the magazine. Eight months after this initial meeting with Wilde, In March or April 1890 the typescripts for The Picture of Dorian Gray landed on Stoddart's desk. Asserting that the novel was too immoral for publication -- and that it encompassed material “which an innocent woman would make an exception to” (Frankel 45) -- Stoddart insisted that he would purify the material, making it "acceptable to even the most fastidious taste" (Frankel 45). Stoddart's authorial atonements to the text were ultimately rendered futile, when the magazine was published in July 1890 Wilde's tale was met with supreme judgment; The Daily Chronicle deemed it poisonous and symptomatic of the “leprous literature of the French decadents” (Frankel 6). This contention is rooted in the coded nature of many of Wilde’s aesthetic illusions, not least “the yellow book” (Wilde, 14), which many critics (Shea; Mandal; Eichner) believe to be a reference to Joris-Karl Huysmans’ 1884 work À rebours, a novel of extreme bourgeois decadence, brimming with overt sexuality.

Given the reception Dorian Gray received, what is curious is the fact that this first publication was a heavily edited version of the original typescript Wilde sent to Lippincott’s (Frankel 38). Most of these alterations were exercised by Lippincott's editorial team led by Joseph Marshall Stoddart, and although some of the edits were to bring the text into conformity with American usage (Frankel 40), many critics (Lawler; Guy and Small; Bristow) also remark on Stoddart’s censorship of Wilde’s proclivity to engage with topics of a homoerotic nature, I discuss some of these below in the section titled "Wilde in Charge". Although Frankel accepts that it may not have been unusual for an American publisher to "assume a position of privilege" over the author and exclude them from editorial decisions (Frankel 42).

In 1891 Wilde published a twenty-chapter book version of the novel through London publishers Ward, Lock & Co. In this edition, chapters 3, 5, and 15 to 18, inclusive, are new. Chapter 13 of the Lippincott’s edition was divided and became chapters 19 and 20 of the novel. Wilde also offers a preface to this version, satirising the virtues of an artist (1891, i).

Since 1891, a myriad of iterations have been published, including the 1909 edition which included a special bibliographical note eluding to the various “pirated” versions circulating at the time (Wilde 1909), and a 1913 stage adaptation (Wilde and Loundsbery). In 1908 Parisian publishers Charles Carrington printed the first illustrated version of Dorian Gray (1908), featuring engravings by Eugene Dete. A tipped in note from the publisher explains that the volume was intended to be published in 1908, the date on the title page, but after the text had been printed the artist fell ill and the book wasn't actually issued until 1910. In 1925, London Publisher John Lane released an authorised version of Dorian Gray (1925), which includes an introduction by author Osbert Burdett and illustrations by Henry Keen. The Timeline to the left shows a selection of editions, with mention of those which are held by the University of Victoria.

Although many subsequent variants were published, Frankel notes that there was a distinct lack of scholarship on the revisions, owing much to the "embryonic state" (Frankel, "A Textual History of The Picture of Dorian Gray") of scholarship on Wilde due in part to the ignominy surrounding Wilde and his sexuality. Donald Lawler’s 1988 edition for Norton Critical Editions demonstrates a shift in studies of Wilde and houses the 1890 and 1891 versions of text alongside each other. The timing of this edition is significant as it was published over a decade after John Espey, a Professor of English at UCLA highlighted the differences between the published editions and the copies of Wilde’s original typescripts that the UCLA library housed (Frankel, "A Textual History of The Picture of Dorian Gray"). Why did the Norton edition, nor the subsequent variorum edition edited by John Bristow and published by Oxford University Press in 2000, make use of these typescripts? Was it merely due to remaining copyright restrictions, or does it allude to my earlier note about the privilege of the publisher (or editor) over the author? As Lawler concluded that the 1891 revised edition enshrines “Wilde’s final intentions” (Lawler x).

Many digital editions of the novel now exist, including a UVic edition of the 1890 Lippincott's variant, edited by James Gifford (Gifford 2011) and published by the University of Victoria’s Special Collections.

In 2011 Harvard University Press published The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition; edited by Nicholas Frankel. Over one hundred and twenty years after its first publication, an edition of The Picture of Dorian Gray exists that is its raw format. Frankel suggests that the date of this publication is fitting, a "timely embodiment of what Wilde meant when he confessed that Dorian Gray is "what I would like to be - in other ages, perhaps"" (Frankel 21).

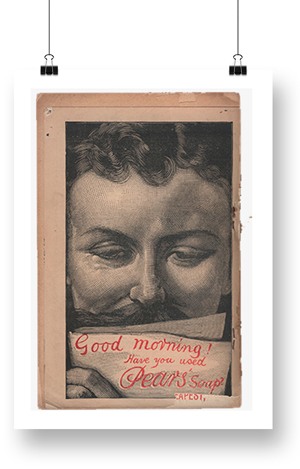

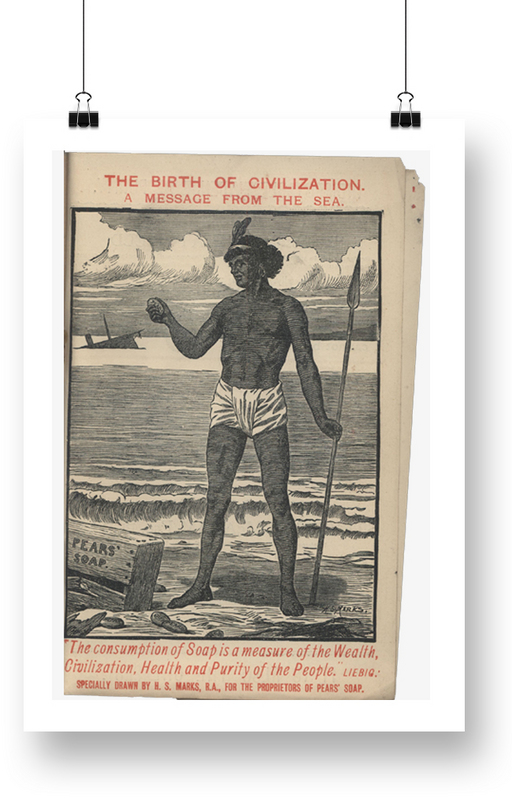

Pears Soap Company - Backpage to Lippincott's Magazine (1890) Featuring The Picture of Dorian Gray

Pears Soap Company - Inside Pages Lippincott's Magazine (1890) Featuring The Picture of Dorian Gray

Pears Soap Company - Inside Pages Lippincott's Magazine (1890) Featuring The Picture of Dorian Gray

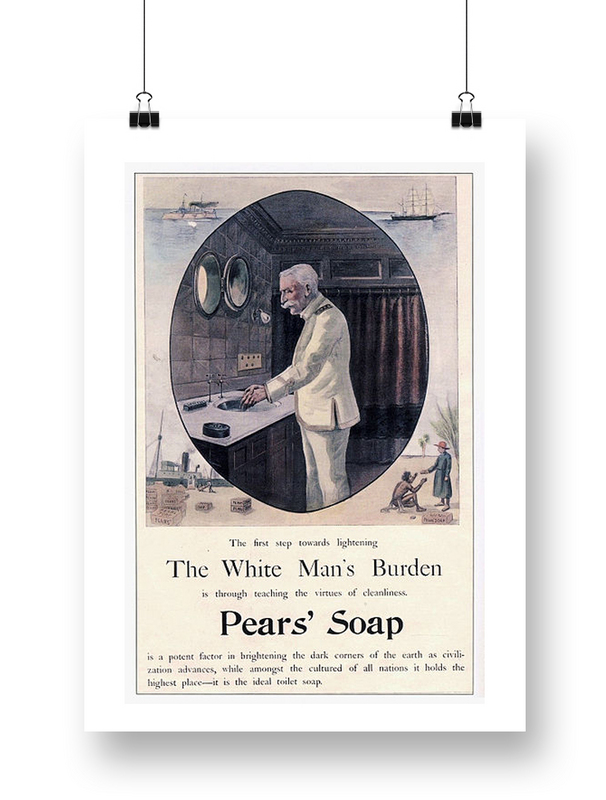

Pears Soap Company Advertisement "A White Mans Burden" (1899) in McClures Magazine (From Norton)

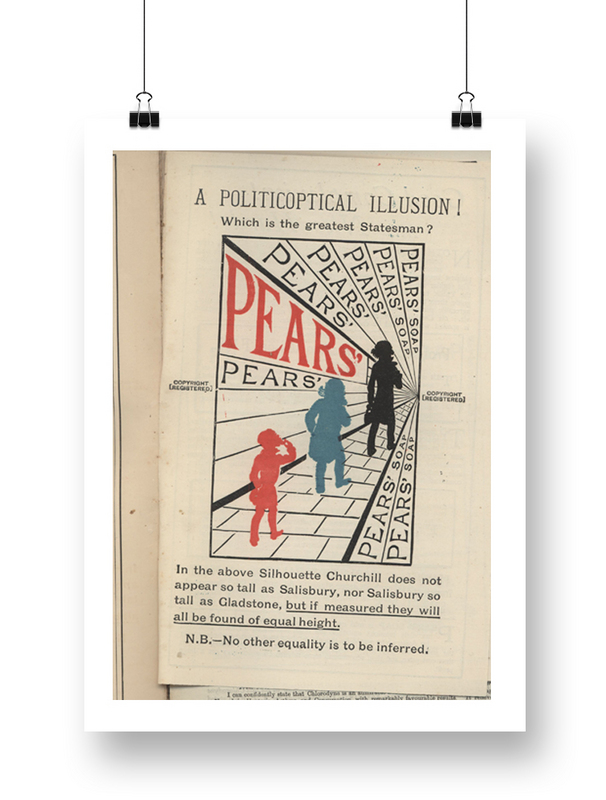

Pears Soap Company Advertisement Insert "Who's the Greatest Statseman?" in The Woman's World (1897)

Pears Soap: Cleansing Victorian Society

"Soap served as an effective instrument of the British imperial project by associating the Victorian virtue of cleanliness with the rhetoric of racial hygiene." (cited Kil 414)

Bibliographical codes are, Jerome McCann argues in The Textual Condition “the “material levels of the text” which “are not regularly studied…typefaces, bindings, book prices, page format, and all those textual phenomena usually regarded as (at best) peripheral to the text” (McCann 12-13). Concerned with McCann’s reluctance to include advertisements within the bibliographical code, for reasons that “their textuality is exclusively linguistic” (McCann 13) Brooker and Thacker offer a set of periodical codes to include, the “use and placement of advertisements” as they constitute both "internal and external” codes, they have association beyond their placement (Brooker and Thacker 13).

The concept of the Paratext - French literary theorist Gerard Genette argues, is that these peripheral features are a mode of control for the reader, the space in between text and off-text, a place of “transaction and influence.” They are not a “boundary or a sealed border” but instead a “threshold” (Genette 1).

Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, published by in Lippincott's periodical in July 1890 is exemplary of the juxtaposition between periodical and linguistic codes. The advertisements that hem Wilde’s narrative exist solely in the threshold, and are complicit in extending, or even producing meaning in his narrative.

In the late nineteenth century, Pears Soap company were explicit in their nurturing of the imperialistic ideal, and soap became commodity culture and physical cleanliness synecdoche for civility. Advertisements for Pears are present in four pages within the Lippincott’s edition of Dorian Gray. The inside back page depicts a picture of the white man as saviour, the boundary of the oceans has been broken and the sea delivers soap like pebbles washed up at the feet on the unclean. In his book Imperial Persuaders: Images of Africa and Asia in British Advertising, Anandi Ramamurthy suggests that images portraying the birth of civilization - and the projection of the brown-skinned savage, portends the period of advertising where mercantile capitalism and imperialist expansions collide with "racial hierarchy" and the doctrine of "naturalisation" (Ramamurty 48). In her book The Adman in the Parlour, Ellen Gruber Garvey suggests that part of Pears' enterprise was the role of "interloper" between consumer and art, and in doing so they posited an aggressive "annexing of high-culture" (Gruber Garvey 102). In other words, the advertiser crosses the boundaries between capitalism and culture, and in doing so offers subversive commentary on the culture; in this case, Wilde's narrative.

An insert in The Woman’s World Magazine, edited by Wilde from 1887 to 1889 is curiously framed by a political illusion featuring three of Britain’s prominent political figures Lord Salisbury, William Gladstone and Randolf Churchill, father of Winston. The disclaimer to this illusion, that “no other equality” between the three statesmen be “inferred” - helps us to understand the sensitivity of the sociopolitical climate of the Victorian era and in turn the complexities of an editor's job in choosing morally defensible material for publication.

Additionally, "The White Man's Burden" Pears' advertisement, based on a poem by Rudyard Kipling - appeared in McClure's Magazine in October 1899 and is reprinted online in the Norton Anthology for The Victorian Age, under a section titled "Victorian Imperialism: Illustrations" (Norton). Soap takes on an implicit religious purpose here, tasked with brightening the dark corners of the world.

If we return to Lippincott’s magazine, The Picture of Dorian Gray sits before the pernicious Pears' advertisement and perhaps something can be said for the “transaction” that takes place in the liminal space between Wilde’s cleansed words and the burden that the white man carries to purify entire continents. We can see this correlation in the fanfare of negative language levied at Wilde: The mephitic odours of moral and spiritual putrefaction..." (Frankel 6) insisted the London Chronicle. “Why go grubbing in Muck Heaps?” (Frankel 6) said the Scots Observer, stating that Wilde makes it unclear as to whether he “prefers a course of unnatural iniquity to a life of cleanliness, health and sanity” (Frankel 6). After such a bathing in the leprous vulgarity of Wilde’s decadent prose, the reader must be sanitized.

The relationship between the audience (off-text) and internal periodical components of the magazine (paratext) is a significant one, an external meaning is constructed implicitly through the advertisements. Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, as published in Lippincott's magazine in 1890 is blanketed in paratextual cogitations, the “fringe” (Genette 2) of advertisements exists as a subversive attempt to oppose the message of Wilde’s work, to determine not what Dorian Gray is, but what they feel is should be, and to align the magazine to the sensibilities of its audience.

Lippincott’s, not Wilde, have the last word, as the back cover is perfectly colonized by Pear’s soap.

Good morning? It asks. Have you used Pears Soap today? Have you ridded yourself of the poison? Purified yourself of the innate sinfulness of Wilde’s hedonistic tale?

Title Page to The Picture of Dorian Gray, as published by Ward, Lock and Company in 1891

Wilde's Preface to the 1891 Edition. Stuart Mason calls the aphorisms Wilde's enunciation of "his creed as an artist" (Mason 20)

Wilde's Preface to the 1891 Edition.

Wilde, Oscar. "A Preface to 'Dorian Gray'" Fortnightly Review (1891) - Prior to the book publication by Ward, Lock and Company, Wilde's added preface was published in London-based periodical Fortnightly Review.

(1891) - Wilde in Charge

"Those who find ugly meanings in beautiful things are corrupt without being charming. This is a fault" (1891 Preface).

Following the publication of The Picture of Dorian Gray in Lippincott’s, Wilde began work on an extended version, which was published in 1891 by Ward, Lock and Co. He expanded the story, adding a number of important scenes such as Dorian’s visit to the opium den in chapter sixteen and the character of James Vane. Bristow suggests his intention was to mediate and soften some of the most evocative dialogue between the three main characters (Bristow lii-lv). Here I will examine a selection of the mediations Wilde did, as well as considering his purpose in doing so: was Wilde, the muted author, hoping to regain authority of his work, or is he distancing himself further from the seething critics?

Prior to the release of the 1891 version, a series of twenty-three aphorisms appeared in The Fortnightly Review under the title ‘A Preface to “Dorian Gray”’ (Fortnightly Review 1891). Many of these adages were taken from letters he had written to his critics, and the Preface was also included in the 1891 edition. Wilde’s ironic suffusion is hard to miss here:

"To reveal art and conceal the artist is art's aim" (1891 Preface).

The moderation of Dorian Gray prior to its publication is Wilde’s very own concealment. The revelation that led to his downfall was the Lippincott’s edition. On April 3rd 1895 Wilde took libel action against The Marquees of Queensberry for accusing him of sodomy. Recorded in Stuart Mason’s Art & Morality (1912), an exhaustive record of the conversations, letters and court transcripts that followed in the years after the release of Dorian Gray. Wilde’s concealment was been exposed, Frankel notes:

Edward Carson, Queensberry’s counsel, began defending his client by using passages from the Lippincott’s text of Dorian Gray - Carson was aware that such passages were considerably muted for the 1891 edition” (Frankel 16)

Most notably of these is the following taken from the original typescript Wilde sent to Stoddart:

“Wait till you hear what I have to say. It is quite true that I have worshipped you with far more romance of feeling than a man usually gives to a friend. Somehow, I had never loved a woman…Well from the moment I met you, your personality had the most extraordinary influence over me. I quite admit that I adored you madly, extravagantly, absurdly.” (2011, 172)

The account of the libel case began with Carson reading Wilde the above passage, and asking him, “You think that is a feeling a young man should have towards another?” to which Wilde replies, “Yes, as an artist” (Mason 208). As Frankel noted above, Carson is open about his decision to read only from the Lippincott’s version:

“Mr Wilde asked for a copy and was given one of the complete editions. Mr Carson, in calling attention to the place, remarked, “I believe it was left out in the purged edition?”” (Mason 208)

Indeed, in the 1891 edition of the text, “Your personality had the most extraordinary influence over me” is the only line here to survive censorship. The first two sentences have been deleted entirely, and the final sentence changed to, “that I dominated, soul, brain, and power by you" (1891).

As Frankel suggests, the romantic, emotional projection of adoration is at once transferred to a more pragmatic position, “lessened…transformed into something more innocuous: the painter's quest for a platonic ideal in art” (Frankel 11). In an effort to defame Wilde’s reputation, Queensberry’s counsel offers the Lippincott’s version of Dorian Gray as the authoritative edition.

The “uncensored”, 2011 edition of Wilde’s work has -- through Frankel’s commitment to the original typescripts -- exposed the evasive nature of the authorial, stable text even further. In Lippincott’s, Lord Henry describes the object of the portrait as a “brainless, beautiful thing” (1890, 5), yet in Wilde’s 1891 publication the word “thing” is changed to the word “creature” (1891, 4). So, if we are to believe Lawler’s earlier comment on the intentions of the author, then the word “creature” was Wilde’s original intention here. However, in the 2011 edition, the word is restored to “thing” (2011, 72). In other words, the typescript (Wilde’s original intention) and the 1891 edition (Wilde’s post-Lippincott’s intention) contradict each other; Wilde has regained some control by editing his own work mid-edition.

Considered as a whole, I suggest that The Picture of Dorian Gray reflects, and in some cases accepts a multifarious authorship. Its first iteration shows the severity of editorial manipulation Lippincott’s undertook to make it more palatable, replete with various “off-text” considerations through the periodical codes.

In its second iteration Wilde edits himself -- satirically charged -- but also wary of the seriousness of the accusations mounting against him. Even the original typescripts, mutilated by various hands including Wilde and Stoddart, demonstrate the weight of responsibility surrounding the narrative.

As a text is born, argues Jean-Paul Sartre, the familial connection between writer and work is severed:

“We hope that our books remain in the air all by themselves and that their words, instead of pointing backwards toward the one who has designed them, will be toboggans, forgotten, unnoticed, and solitary, which will hurl the reader into the midst of a universe where there are no witnesses” (Satre 158).

Authorship, then, is post-writer and post-work, while Wilde may hold credit for having “written” The Picture of Dorian Gray, it has been recorded and remediated, and it continues to be so, for all who read it.

“It is the spectator, and not life, that art really mirrors“ (1891 Preface).

Bibliography

The Picture of Dorian Gray: Editions Used

Wilde, Oscar. "The Picture of Dorian Gray". Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine, Ward Lock & Company, London, 1890.

---. The Picture of Dorian Gray. Ward Lock & Company, London, 1891.

---. The Picture of Dorian Gray. C. Carrington, Paris, 1909.

---. The Picture of Dorian Gray. illustrations by Henry Keen, J. Lane, London, 1925.

---. The Picture Of Dorian Gray. Ed. by Donald Lawler, New York: Norton, 1988.

---. The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde: Vol. 3, the Picture of Dorian Gray: The 1890 and 1891 Texts. Ed. by Bristow, Joseph. Oxford, 2000.

---. The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Ed. by Nicholas Frankel, Harvard University Press, 2011.

Digital Editions Used

Wilde, Oscar. "Differences between the 1890 and 1891 editions of The Picture of Dorian Gray". Github Repository, http://mdoege.github.io/Dorian_Gray_diff/#difflib_chg_to0__1. Accessed 5 December 2016.

---. The Picture of Dorian Gray 1890. Ed. by James Gifford, The University of Alberta Website, UVIC Special Collections, 2011, https://sites.ualberta.ca/~gifford/dorian/dorian.pdf. Accessed 21 October 2016

---. The Picture of Dorian Gray 1891. Edited by Judith Boss, Project Guthenberg, 2008, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/174/174-h/174-h.htm. Accessed 21 October 2016,

Works Cited

Brooker, Peter and Andrew Thacker eds. The Oxford Critical and Cultural History

of Modernist Magazines. Vol. 1: Britain and Ireland: 1880-1955. Oxford UP, 2009.

Eichner, Hans. "Against the Grain: Huysman's A Rebours, Wilde's Dorian Gray, and Hofmannsthal's Der Tor und der Tod." In Narrative Ironies, Ed. by Gerald Gillespie and A. Prier, Rodopi, 1997.

Frankel, Nicholas. "A Textual History of The Picture of Dorian Gray". Harvard University Website, 2011, http://harvardpress.typepad.com/hup_publicity/2011/02/textual-history-picture-of-dorian-gray-frankel.html, Accessed 21 October 2016.

Gennette, Gerard. Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Gruber Garvey, Ellen. The Adman in the Parlor: Magazines and the Gendering of Consumer Culture, 1880s to 1910s. Oxford University Press, 1996.

Huysmans, Joris-Karl. Against Nature (à Rebours). Trans. by A.A. Mandal, Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. 1998.

Kil, H. R. "Soap Advertisements and Ulysses: The Brooke's Monkey Brand Ad and the Capital Couple." James Joyce Quarterly, vol. 47 no. 3, 2010, pp. 417-426. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/jjq.2011.0024, accessed 15 November 2016.

Mason, Stuart, 1872-1927. Oscar Wilde, Art & Morality: A Record of the Discussion which Followed the Publication of "Dorian Gray", F. Palmer, London, 1912.

McCann, Jerome J. The Textual Condition, Princeton University Press, 1991.

Mckenna, Neil. The Secret Life Of Oscar Wilde. Random House, 2011.

"Pears' Soap Advertisement, The White Man's Burden". The Victorian Age: Topic 4: Illustrations, The Norton Anthology of English Literature, 2010-2016, https://www.wwnorton.com/college/english/nael/victorian/topic_4/illustrations/imburden.htm, accessed 12 December 2016.

Pearson, Hesketh. Oscar Wilde: His Life and Wit. Harper and Bros., 1946.

Ramamurthy, Anandi. Imperial Persuaders: Images of Africa and Asia in British Advertising. Manchester UP, 2003.

Shea, C. M. "Fallen Nature and Infinite Desire: A Study of Love, Artifice, and Transcendence in Joris-Karl Huysmans's Á Rebours and Oscar Wilde's the Picture of Dorian Gray." Logos: A Journal of Catholic Thought and Culture, vol. 17, no. 1, 2014., pp. 115-139.

Sartre, Jean-Paul. What Is Literature? Translated by Bernard Frechtman. Washington Square Press, 1966.

Wilde, Oscar. The Letters of Oscar Wilde: Correspondence. Ed. by Rupert Hart-Davis 1907-1999, Harcourt, Brace & World Inc, New York, 1962.

Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray: From the Romance of Oscar Wilde: A Play in Three Acts and Prologue. Edited by Grace C. Loundsbery and Lou Tellegen, Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent, 1913.

Wilde, Oscar. ""A PREFACE TO 'DORIAN GRAY.'"." Fortnightly review, May 1865-June 1934, vol. 49, no. 291, 1891., pp. 480-481.

Further Reading

Gomel, E. "Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray, and the (Un)Death of the Author." Narrative, vol. 12 no. 1, 2004, pp. 74-92.

DM/Fall 2016