Walking by Henry David Thoreau (1914)

Introduction to Walking: The Preamble

“I wish to speak a word for Nature, for absolute freedom and wildness, as contrasted with a freedom and culture merely civil... I wish to make an extreme statement—"

Credited by Andrew Menard as “perhaps his most original essay on nationhood and national culture,” Henry David Thoreau’s Walking stands as a cornerstone commentary of the nineteenth-century American political and philosophical zeitgeist (591). I want to focus on Thoreau’s use of the words “speak” and “extreme statement” in his introduction to his Walking manifesto. This declaration suggests Thoreau intended his commentary on the art of sauntering to be spoken aloud in an emotive lecture to the citizens of Concord, Massachusetts (3).

In the “Introductory Note” from the 1914 Riverside Press edition of Walking, as accessed from University of Victoria Special Collections, the editor notes how Thoreau’s commentary was “perhaps” originally spoken as a lecture and published henceforth in fragments, “scattered through his journal” (v). Before the posthumous release of this version, Thoreau’s Walking essay was “never before... published in separate form” (v). Thoreau’s commentary on the philosophical, political, and spiritual importance of walking followed a progression of “stages” (v). These stages involved various mediums as a lecture, then journal entries, and a journal article in The Atlantic Monthly in June of 1862 before achieving the “permanency of publication” in this specific version, pictured above (v).

What happens to Thoreau’s philosophy when his speech on the importance of walking, movement, and political agitation is solidified into a singular, cohesive text? This edition, being the first to contain Walking in its linear entirety, represents a separate entity with ramifications for readers of Thoreau and subscribers to his ideologies. The “permanency of book form,” which this edition offers, produces a solidifying effect on Thoreau’s stance on the importance of walking in the face of “servile” civility (introduction, 83). In a paradoxical twist on any intuitive assumption, does solidifying Thoreau’s Walking help to empower (or, more naturally, disempower) his claims?

In his essay on “‘A False Position in Society,’” Thoreau scholar Robert Milder delineates Thoreau as wholly committed to the transcendentalist movement, which honours the self as vocation enough amongst a society of busy men and women (4). This “self-culture” idealises being a “man of action,” a philosopher, and, most importantly, “a writer” (4). Sauntering, then, takes on a new calibre of meaning as a tool necessary for self-awareness and as a rejection of individual and societal stasis. To “liv[e] for” his own “inward growth” was Thoreau’s ultimate goal (4). Such movement, both literal and figurative as part of a philosophical school of thought and vitalized through his musings and his writing, was integral to Thoreau.

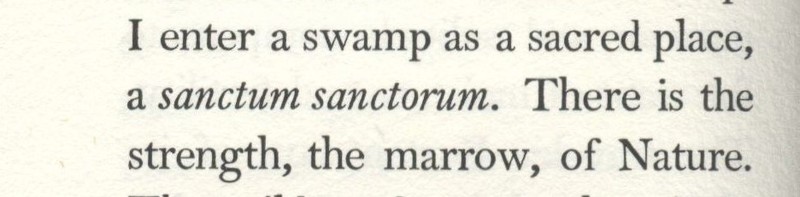

While I highlight the importance of this specific 1914 version of Walking, which offers readers for the first time the consolidated essay, I simultaneously suggest that solidifying Thoreau’s vision into one text renders it counterintuitive to sauntering, whether that be through space, history, or alternative printing mediums. The best way to remedy this potential negation of Thoreau’s philosophy is to walk through the unique features of this text in a way that revitalises it. I will focus on the unique elements of this Riverside Press edition such as the introductory note, the single illustration, and the publishing company itself. This reanimation process will ideally mirror Thoreau’s philosophies. I hope this exhibit pays tribute to the tax resistor, naturalist, and abolitionist Thoreau himself.

A quotation from Jonson followed by Thoreau's response (Walking 51).

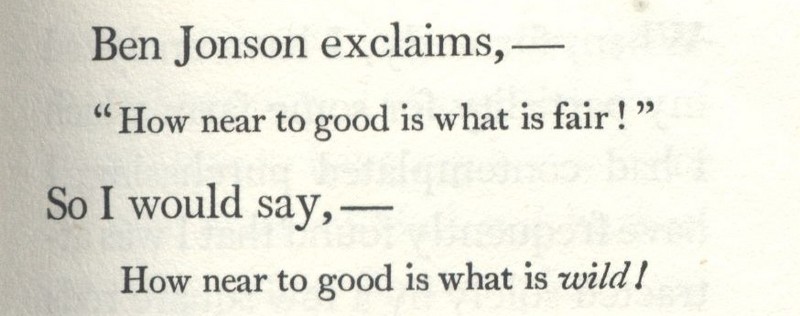

Henry David Thoreau, "Photograph of a Portrait from Life," from Marble's Thoreau: His Home, Friends, and Books.

Latin text distilling Thoreau's philosophy (Walking 56).

The Ambling Author

To take the first step, I must foreground this 1914 edition by describing Thoreau’s character and philosophy. Henry David Thoreau of Concord, Massachusetts is best known for his collaboration in the American transcendentalist movement with Ralph Waldo Emerson. Joel Porte outlines a “double consciousness” inherent within transcendentalism in Consciousness and Culture: Emerson and Thoreau (1). Above all, “passion,” “fervent searching,” and hyperbolic expression define this nineteenth-century campaign (12). These three paramount elements of transcendentalism contrast against the “dangerous symptoms of modernity,” the “subjectiveness” and “inner dissociation” as outlined by Emerson (2).

Transcendentalism was a rebuttal to the dualism that Emerson believed was inherent within the Romantic tradition. Such a dualism, Emerson asserts, was between “earthly lust” and “spiritual strivings” (4). Dualism or none, it must be acknowledged that both transcendentalists and romantics reveal a shift from radical “empiricism” to the spirit as a “source of knowledge” (Knirsch). Despite Emerson’s assertions, then, romantics and transcendentalists should rather be viewed as “interdependen[ts]” than adversaries (Knirsch 1). As evidenced by Thoreau’s own dissonance, transcendentalists were certainly not exempt from this dualism of self and nature. This dualism, then, is a dualism within rather than a dualism between.

The paradox of Thoreau’s inherent dualism is represented by his aggressive desire to saunter, to disrupt status quo, to gain spiritual and bodily mobility contrasted with his geographical stasis. Underscoring this paradox further is that this 1914 Riverside Press version of Walking was published in Thoreau’s home state, Massachusetts. By default, this volume suggests Thoreau's life is contained within a singular geographical region, as compared to the mobility and transience inherent within the Atlantic Monthly publication of Walking. This solidification of authorship and the landscape relating to Thoreau may run counterintuitive to his philosophy. In her book titled Thoreau: His Home, Friends, and Books, Annie Russell Marble suggests that “Thoreau and Concord are interdependent,” complementing each other in an inextricable bond (3). Much like his footsteps, the “wooded..landscape” of Concord has been “stamped” with Thoreau’s philosophy (3).

Thoreau’s alliance with the natural Concord ecosystem appears to negate his philosophies regarding mobility and exploration. In Walking, he asserts how “no wealth can buy the... leisure, freedom, and independence” inherent in the act of walking, of movement (8). Thoreau then asserts the ultimate prerequisite for walking: “having no particular home, but equally at home everywhere” (4). If this be the case, his philosophy is problematized by his ardent devotion to Concord alone. This could be interpreted as a symptom of dualism, of dissonance such that Emerson critiques, in Thoreau’s manifesto. However, I argue this dualism, this definitive contradiction, is necessary in order to resist stasis. Should Thoreau’s ideologies remain consistent and unchallenged, his vagabond identity, like his Walking essay, risks solidification.

His identity becomes muddled by this volume of Walking, which by the location its publication defines him in relation only to the region of Massachusetts. Consequently, Thoreau’s vision is literally bookended by the publisher, thereby forcing him into the realm of public critique. In Walking, Thoreau quotes the English metaphysical poet Ben Jonson, who states “how near to good is what is fair!” (Walking 51). Thoreau disputes Jonson, claiming “how near to good is what is wild!” How wild can a philosophy be, however, if it is constricted between the covers of a single volume?

The classic insignia of The Riverside Press circa 1852, depicting Pan playing his flute amongst the picturesque landscape. For comparison purposed, see below for the title page of this 1914 volume of Walking. Digitized by the University of California.

Illustration of Pan appearing on the title page of the Riverside Press 1914 edition of Walking.

Projected Development of The Riverside Press, 1852-1911. Published by The Riverside Press & Digitized by the University of California.

Image displaying specific copy of this volume of Walking from The Riverside Press.

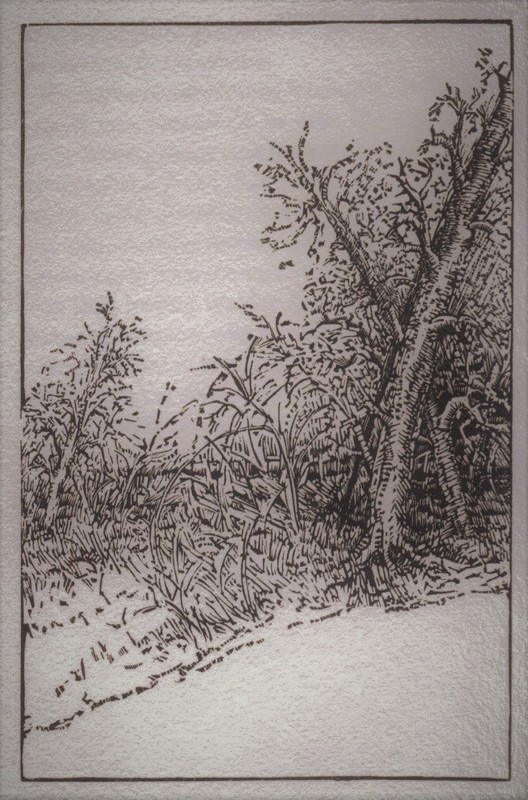

A swampy illustration appearing in Thoreau's first journal fragment in Thoreau, Two Fragments from the Journals (1968).

Illustration for first page of Thoreau's Walking from The Riverside Press, 1914 (3).

The Progressive & Picturesque Riverside Press

Described as a “most distinguished and successful American [publisher]” in their 1911 information booklet, the Riverside Press was founded in 1823 by Henry O. Houghton. “Situated on the banks of the Charles River,” the (literal) Riverside Press cannot help but dominate the landscape of nineteenth-century Massachusetts. It appears intuitive that such a touchstone publishing company should acquire the rights to publish and solidify Thoreau’s Walking essay as an integral text to an expanding American vision. However, to position Walking, which argues against the “never-ending enterprises” of industrial America amidst the crux of expansionism is to contradict Thoreau himself (10).

The Riverside Press printed 550 copies of this essay in the same form, shown in the image to the left. This adds a dimension of commercialization to Thoreau’s philosophies contained within this volume. However, the limited number of Walking copies distributed by this company complicates this theory and suggests that the distribution and sales of the essay itself were not as anticipated or that the company was limited in funds. One final factor which solidifies the contradictory relationship between The Riverside Press and Thoreau himself is evidence in the “Introductory Note,” which mentions how Thoreau, restrained by “illness” on his deathbed, finalised and approved this version of the Walking essay (v). His vision on mobility and agitation is thus preserved, representing a snapshot of his beliefs at the point of the ultimate stasis: his death. This fact is underscored by the unified Riverside Press edition.

I want to take a turn here and discuss the illustration, pictured to the left, which appears on the first page of Thoreau’s essay in this Riverside Press edition. With its beaming sun and gnarled deciduous trees, the snaking path through the long meadow grass, and rolling hills which seem to extend indefinitely, this scene represents the archetypal picturesque. In The Beautiful, the Sublime, and the Picturesque in Eighteenth-Century British Aesthetic Theory, John Walter Hipple defines the picturesque as a scene which provides the painter with a perfect scene: “a well-composed picture, with suitably varied and harmonised form, colours, and lights” (186). The landscape, then, must be a balance of poetics and nature, capable of artistic representation. Hipple also asserts the picturesque as of the “romance origin” (185). With respect to this illustration preceding Thoreau’s Walking, this 1914 edition draws Thoreau’s transcendental philosophy back into the realm of the Romantic tradition. Is this another example of the implicit negation of his manifesto, as committed by The Riverside Press?

On page 56 of this version of Walking, Thoreau heralds the swamp as a “sacred” space, a “sanctum sanctorum.” According to Thoreau, it is the swamp, not the picturesque landscape, which constitutes the “marrow” of nature (56). Thoreau’s view of nature as not a picturesque landscape but a rich, dank, fertile space is problematized by the illustration that occurs on the first page of his Walking essay in the Riverside Press volume. Rather than represent the swamp, this illustration epitomises the picturesque. Indeed, standing in stark contrast is an illustration appearing in Thoreau’s first journal fragment, published by The Windhover Press in 1968 and also featured in University of Victoria Special Collections. The illustration depicts a lush cluster of marsh reeds situated amongst the base of a leaning alder tree (see image to the left). As alders prefer marshy environments, I assume this illustration is depicting the type of marsh that Thoreau heralds in his Walking essay.

This calls into question the picturesque, romanticised illustration which precedes the 1914 Riverside Press volume of Walking. Since illustrations set the tone of literary pieces, this landscape suggests that the subsequent essay will adhere to the Romantic tradition rather than introduce a relatively radical manifesto. This underscores the power that a publisher such as The Riverside Press holds not only on the body of work in question but over the perceptions of readers themselves. Finally, the contrasts in nature between the Walking landscape and the journal fragment underscore an inherent dualism between Thoreau’s philosophies and the publishing medium, further suggesting the dynamism of his beliefs. This dynamism is strengthened by the presence of the gate in the picturesque illustration, which has been trampled over. This symbolises Thoreau himself trampling over the various theoretical lenses imposed on his philosophies. Again, I argue this dualism mobilises rather than restricts him as an author.

Trudging Through Text

"As if they had been named by the child's rigamarole, Iery wiery ichery van, tittle-tol-tan."

One potential repercussion of solidifying Walking into a singular text reveals itself through the five languages Thoreau employs, displayed in the gallery to the left and quoted above from page 73. In sequential order as they appear in Walking, I’ve digitised the following: a French phrase, a Latin phrase, an excerpt from the Chaldean oracles (a fragmented poem from the second century, A.D.), and a Spanish phrase. In fragments, these snippets of various languages are compelling, hinting at Thoreau’s Harvard level of education as outlined by John Broderick in his essay on “The Movement of Thoreau’s Prose” (324). While such wielding of foreign phrases was common in nineteenth-century literature, these glimpses into his academic mind afford Thoreau credibility amongst his readers, who were, at the time of Walking, comprised largely of the laymen and women of Concord. Brought together in a single text, however, as per this version of Walking, these phrases suggest that Thoreau’s critique extends beyond the small region of Concord and risk distancing him from his audience. However, given the relatively expensive cost of each 1914 copy, Thoreau's readers may have occupied a upper-middle class, and thus wealthier, demographic.

Regardless, the inclusion of several languages in his essay solidifies Thoreau as an educated man. Despite his “reluctance to leave his native town,” Thoreau implies that he has sauntered far from Concord to obtain his education and has willingly returned. Due to the inaccessible nature of these excerpts for many of Thoreau’s readers, specifically that from the Chaldean Oracles, Thoreau’s philosophy emanates an air of sophisticated, abstract, and distant intellectualism. These associations impact readers’ perceptions of Thoreau’s true self, a young man unsatisfied and disillusioned with highbrow academia (Broderick 325). As an aside, the University of Victoria Special Collections boasts many authoritative versions of Thoreau's philosophical essays, including a 1910 edition of Friendship, Love, and Marriage published by the New York company East Aurora, as well as the 1970 version of Huckleberries, published by the equally credible Windhover Press. Alike these listed versions, this 1914 Riverside Press edition of Walking seems the most remote of all in which the author, at the mercy of the publishing medium, ambles further from his audience.

1862 Issue of The Atlantic Monthly featuring essays from Thoreau. Retrieved from The Thoreau Society.

The Atlantic Alliance: A Lighter Step

“if one habitually manifests fear at the utterance of a sincere thought... his life is a kind of nightmare continued in broad daylight.”

In the “Introductory Note” to this 1914 edition, the editor states how The Atlantic Monthly magazine published Walking as a fragmented essay in 1862, thanks to edits made by his sister Sophia (v). A quick search yields a remastered version of this 1862 Walking tribute. Because this is an electronic version offered on the magazine website and, according to the “Introductory Note” was not originally a cohesive essay, this version is still far from being the authoritative text as represented by The Riverside Press. Still, as Susan Goodman observes in Republic of Words: The Atlantic Monthly and its Writers, 1857-1925, The Atlantic Monthly maintains “a long tradition of publishing nature essays” by Thoreau (80).

In 2015, The Atlantic Monthly published an assertive article titled “In Defense of Thoreau” by Jebediah Purdy. Purdy argues that Thoreau is contradictory in nature. Thoreau is more than a “hypocrite,” however; he is instead a writer who “record[s] the strange variety of own perspectives” (Purdy). With respect to social injustice, as evidenced by his commentaries on slavery, Thoreau remains consistent (Purdy). This is just the most recent example of the literary alliance formed between Thoreau and The Atlantic.

Purdy’s article illuminates two important conclusions: the first, that contradiction is inherent and important in Thoreau’s literary presence and the second, that The Atlantic Monthly maintains a philosophical alliance with him. True to his mercurial nature, Thoreau “vowed to have no further dealings with” The Atlantic Monthly when editor James Russell Lowell edited out a sentence from his essay detailing his trip to Maine (The Thoreau Society). Thoreau responded to Lowell’s harsh editing by asserting how “if one habitually manifests fear at the utterance of a sincere thought... his life is a kind of nightmare continued in broad daylight” (Goodman 80). When Lowell was replaced “a few years later,” Thoreau was delighted to contribute to the magazine once again before his death in 1862 (The Thoreau Society). The Atlantic Monthly has published his essays and his praises ever since. The Atlantic Monthly thus allows Thoreau’s philosophies to remain animated posthumously.

Should readers accept what critics assert about Thoreau and what he declares regarding his contradictory nature, then this 1914 version of Walking takes on an equally important role in revitalising him as an author. I return to my initial question, does this authoritative version negate Thoreau’s philosophies on mobility and wildness? Rather than maintaining Thoreau’s philosophical stance on sauntering as a mere essay and a speech, The Riverside Press presents a bound item reflecting a permanent state. At first glance, this seems counterintuitive to Thoreau’s as a man, as a philosopher, and as a saunterer. With respect to Thoreau’s dualism, such as that Porte outlines in his book, these contradictions are integral to his multifaceted influence over critics and scholars (10). This 1914 volume of Walking by The Riverside Press offers a necessary stepping stone for readers to witness his manifesto in full. It also reminds Thoreau’s readers that, despite the permanency of publication, he cannot be pinned down; his single consistency is his wildness against political injustice and against stasis. And so, despite the static form of his version, his presence in American literature saunters on.

Works Cited

Broderick, John. "The Movement of Thoreau's Prose." The Recognition of Henry David Thoreau: Selected Criticism since 1848. Ed. by Wendell Glick. University of Michigan, 1969. 324-334.

Goodman, Susan. Republic of Words: The Atlantic Monthly and its Writers, 1857-1925. New England University, 2011.

Hipple, John Walter. The Beautiful, the Sublime, and the Picturesque in Eighteenth-Century British Aesthetic Theory. Southern Illinois University, 1957.

Knirsch, Christian. "The Romantic Veil (of Perception): American Transcendentalism and British Romanticism as a Continuation of Lockean Empiricism." COPAS, 12, 2011.

Marble, Annie Russell. Thoreau: His Home, Friends, and Books. New York: AMS Press, 1969.

Menard, Andrew. "Nationalism and the Nature of Thoreau's 'Walking.'" The New England Quarterly, 85, 4, 2012. 591-621.

Milder, Robert. Reimagining Thoreau. Cambridge University, 1995.

Porte, Joel. Consciousness and Culture: Emerson and Thoreau Reviewed. Yale University, 2004.

Purdy, Jebediah. "In Defense of Thoreau." The Atlantic, October 2015. http://www.theatlantic.com/science/archie/2015/10/in-defense-of-thoreau/411457/. Accessed 10 December 2016.

The Riverside Press: Cambridge Massachusetts. The Riverside Press, 1911. Digitised by the University of California.

Thoreau, Henry David. Walking. Massachusetts: Riverside Press, 1914.

---. Thoreau, Two Fragments from the Journals. Ed. by Alexander C. Kern. Windhover Press, 1968.

---. "Walking." The Atlantic Monthly, 657-74, June 1862.

The Thoreau Society. "Writings." The Thoreau Society, 2015. http://www.thoreausociety.org/basic-page/writings. Accessed 11 December 2016.

"In Wildness is the preservation of the world." (Walking 21)

CA/Fall2016