The Statutes of The Order of the Garter (1553)

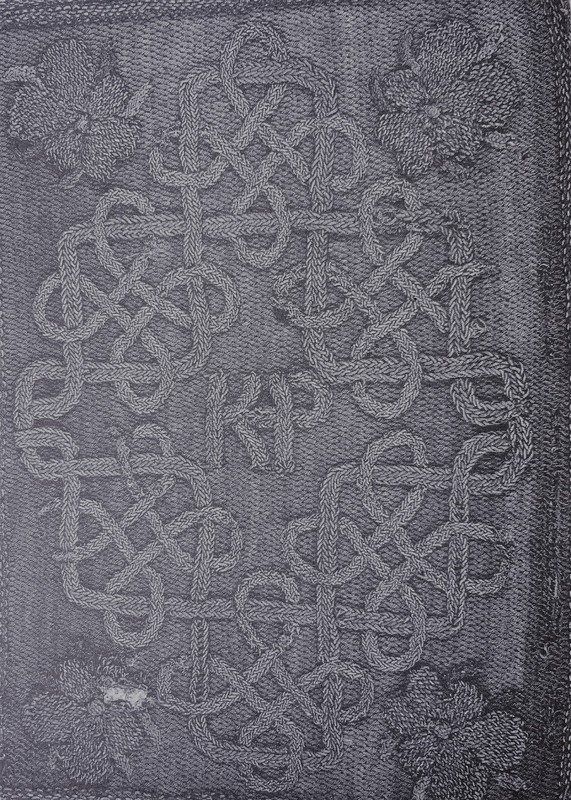

The Cover of the Statutes of the Order of the Garter (1552) (MS Brown Eng 1 - Special Collections, University of Victoria)

Origins and History of The Most Noble Order of the Garter

The Statutes of the Order of the Garter (1553) is a manuscript created at the behest of the young King Edward VI. It contains the amended statutes set forth by Edward and was written by the Chancellor of the Order, William Cecil. Within a year of the creation of this book the King would be dead and all amendments abolished by his sister, the new Queen Mary I.

The Order of the Garter was founded by King Edward III in 1348. A common legend addressing the origins of the Order tell of a ball in the court at Calais at which the Countess of Salisbury was dancing. During the dance her garter is said to have slipped from her leg, eliciting laughter and derision from the assembled courtiers. The King then picked up the garter and presented it to her, saying "Honi soit qui mal y pense" or "shame on he who thinks evil upon it". This phrase however, is believed by historians to have referred to the King's claim on the French throne. It is also believed that the garter originates from the straps used to fasten the knight's armour.

(www.stgeorges-windsor.org)

Membership

Membership in the order is awarded to citizens of the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth and it is considered the third highest honour in the realm, following the Victoria Cross and the George Cross. The emblem bears the arms of Saint George wrapped by a garter bearing the motto of the Order. Membership is limited to the Monarch, the Prince of Wales, and 24 Companions. The order may also have a larger number of supernumerary members comprised of members of the Royal family and foreign royalty.

Members may, in extreme cases, be degraded upon conviction of a number of serious crimes: treason, battlefield cowardice, or actively bearing arms against the Monarch. The last formal degradation occurred in 1716, and involved all the members following the Order King of Arms to St. Georges Chapel. Upon arrival at the Chapel a herald removed the Duke of Ormonde's banner, helm, crest, and sword. The members then proceeded to kick them down the aisle, out of the Chapel, and into the gutter (www.stgeorges-windsor.org).

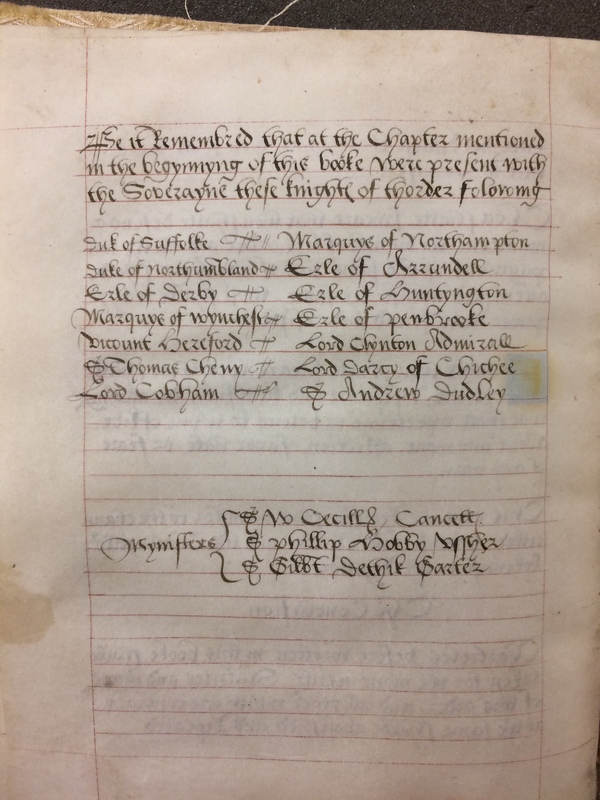

Manuscript - Special Collections, University of Victoria

Shelf Mark: Ms.Brown.Eng.1

Location: Brown Collection Box 1 (Acc. 1989-069, Item #8)

This manuscript contains the Statutes of the Order of the Garter as amended by King Edward VI. The manuscript is complete, but has a number of modern alterations and additions. The codex has been rebound with an embroidered cover with four blue silk ribbons (the binding is modern, but the specific date of manufacture is unknown). The original binding has degraded and the first gathering has come loose. The pages measure 22 cm x 16 cm and are ruled with margins in plummet.

There is a decorative frontispiece on Folio 2 verso. The frontispiece is an illuminated emblem of the contemporary Order of the Garter ca. 1552-53. The emblem contains the arms of St. George and the King of England. The frontispiece has degraded due to the corrosion of the silver leaf.

All text is written in an ornamental secretary script in single columns. It is believed that the scribe hand is that of the Chancellor of the Order - Sir William Cecil - as it matches an example in British Library MS Cotton Nero C.X. that is suspected to be in his hand (Terepocki and Oldfield).

Provenance

The manuscript was part of a collection donated by Bruce and Dorothy Brown. The collection contains items ranging from ca. 2000 BCE to 1970 CE. In the biographical sketch on the University of Victoria Special Collections webpage the Browns are described as "collectors of rare documents of antiquarian interest", and that the purpose of the Brown collection is "to bring together a variety of documents to expose students to documents of historic interest or beauty" (Bruce and Dorothy Brown Collection).

The Embroidered binding of the Statutes (MS Brown Eng 1 - Special Collections, University of Victoria)

Image of an embroidered book cover made for Queen Katherine Parr by her Stepdaughter, Elizabeth Tudor. It contains an initial cipher. These were quite popular at the time the book was made. (Frye)

Image of an embroidered book cover made for Queen Katherine Parr by her Stepdaughter, Elizabeth Tudor. (Frye)

The Binding

By embodying what folklorist Simon Bronner calls "the weave of these objects in everyday lives and communities," the object evokes the historical subjects who once used or fashioned it. - Susan Frye

Bound to Use

The cover of MS Brown Eng 1 is particularly captivating and unique. Hand embroidered bindings took a great deal of time and skill and were often reserved for "religious books such as Bibles, Psalters and Prayer Books, and on presentation copies, often for clergy or members of the royal family" (Marks). It is fitting then, that the embroidery adorns a unique historical manuscript that is firmly within the orbit of the monarchy of England.

The embroidered binding of MS Brown Eng 1 is not the original binding. The vibrancy of the colours and intact threadwork, along with the absence of such common additions as pearls and metallic threads, indicate a relatively modern work. It is impossible to associate a date with the current binding without considerable additional research or material analysis. In this instance, the addition of a modern binding to an early modern manuscript serves an additive function. The original binding was no doubt in a state of disrepair, and this beautifully stitched binding gives the manuscript a new life.

The Present and the Past - Kings, Queens and Covers

The Statutes of the Order of the Garter is a document of wealth and privilege, created within a firmly patriarchal society. There is no hint within the text of the feminine or, literally, of the existence of women. It is a document that clearly shows that men had a firm grasp on power, and that women were rarely, if ever, considered important to the process and function of government. This is incredibly ironic, in light of subsequent events and the material nature of this very manuscript. As noted above, within a year of the creation of this document the young king would be dead. His chosen successor was a distant female relation, and her rival to succession his sister. Ultimately the amended statutes of a male bastion of power and privilege would be undone by a woman. In fact, the next three monarchs of England following Edward VI would be women: Lady Jane Grey, Mary I, and Elizabeth I. Though the written text of the manuscript seems on first reading to support the notion of a nation where women held no power, the reality is much different.

It is true that women were not, until the successions of the Tudor Queens, deeply involved in the day to day operations of government. This does not mean that they did not have methods of inserting themselves into such conversation. While they spent time in chambers undertaking the arts and education expected of any young lady, the women of the court wrote letters and influenced their world in subtler ways. In the book Pens and Needles, Susan Frye discusses the ways many women of that era entered the discourse and decisions of the day. For the young Princesses Mary and Elizabeth, there was always a certain amount of danger given their relative positions at court. One way to avoid this danger was to remind those who had power of your existence and your devotion.

Elizabeth was a particularly skilled embroiderer, as seen in the images to the right, and used her skills to adorn books filled with marginalia and notes that she would present as gifts to her father, stepmother, and brother. In one such text, a hand-embroidered translation of Marguerite de Navarre's The Glass of the Sinful Soul she asks her stepmother Catherine Parr to "rub out, polish, and mend (or else cause to mend) the words (or rather the order of my writing), the which I know in many places to be rude and nothing done as it should be" (Frye 2). Though she professes to "be rude" and do "nothing . . . as it should be", we can see that the young princess is engaging in a highly skilled way in court politics. She is offering herself to her stepmother, to be corrected as seen fit, so as to maintain a position as close to the centre as possible. The text is important, but the image of the embroidered cover is also a signifier of considerable meaning: "The visual and verbal combinations that privileged people commissioned as impresas and coats of arms, engraved withing rings, and had embroidered on their clothing demonstrates the allure that multivalent expression had for the culture . . . [c]ombining words and images made the best possible use of time, brought great truths into human reach, recreated the senses, and stimulated the beholder to [marvel]" (Frye 4). In this simple act, the young Elizabeth is exhibiting many of the diplomatic qualities that would someday see her ascend the throne and become one of the most powerful monarchs of Europe.

There is a connective thread that binds this text intimately with the feminine. The text itself would be rendered meaningless by its creator's sister, and the manuscript would eventually be firmly bound with an adornment that would have been linked with feminine arts in the era of its original manufacture. The women of England are negated from the text, but through the physical materiality of the book their voices rise out of the silence, demanding to be heard. Frye, in discussing the material presence and history of women, says: "All of these objects have been torn from their original contexts, have been moved, overpainted, rearranged, or otherwise meddled with. Nevertheless, they and their represented counterparts offer evidence of early modern relations between subject and object, between textual and everyday practice, that may help in recovering the significance of multiple kinds of texts in women's everyday lives - evidence that, in turn, offers ways to reread early modern literature by both men and women" (Frye 27-28, authors emphasis). In this manuscript we can see an inversion of this meddling. The cover may be a modern addition, but the very nature of the art links it in an effective way with the manuscript past - engendering it with meaning.

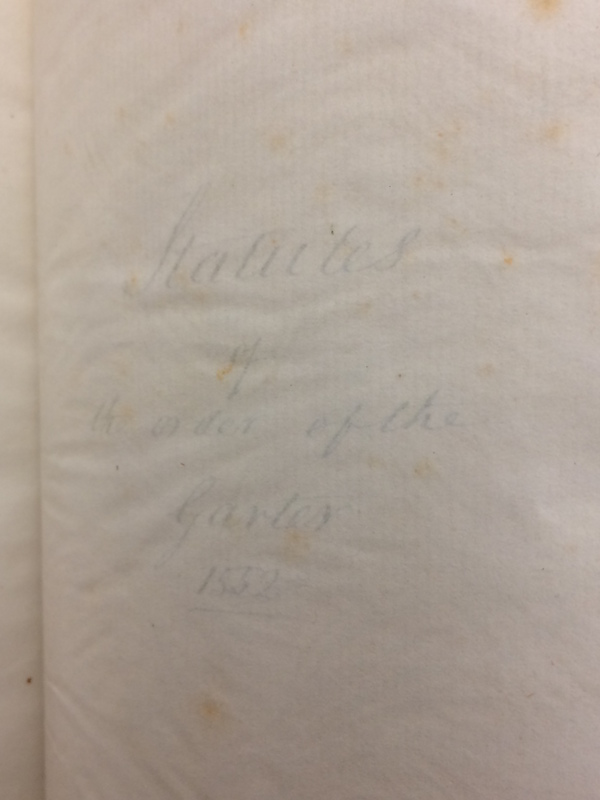

Verso of the binding flyleaf. A title page that is not of the original manuscript. (MS Brown Eng 1 - Special Collections, University of Victoria)

Reflections

This is the verso of a title page that was added to the original manuscript. It is only visible from the reverse as the later binding has been attached to it. The image has been reversed so that it may be easily read:

Statutes

of

the order of the

Garter

1552

Is it important to translate that which is unreadable? In this case I have taken an intriguing and ghostly image, that was illegible to most people, and digitally altered it to allow understanding. Is this an additive or a deductive practice? Now the text can be read, but it is found to simply be a title, and is not even of the original manuscript. Once again we have multiple levels of textual intervention and alteration. In these acts we remove ourselves further and further from the centre - the manuscript. Such interventions "thrust us onto a stage where there is nothing but simulations. Society itself is fashioned into a mirrored, self-reflexive spectacle" (Deibert 194, authors emphasis).

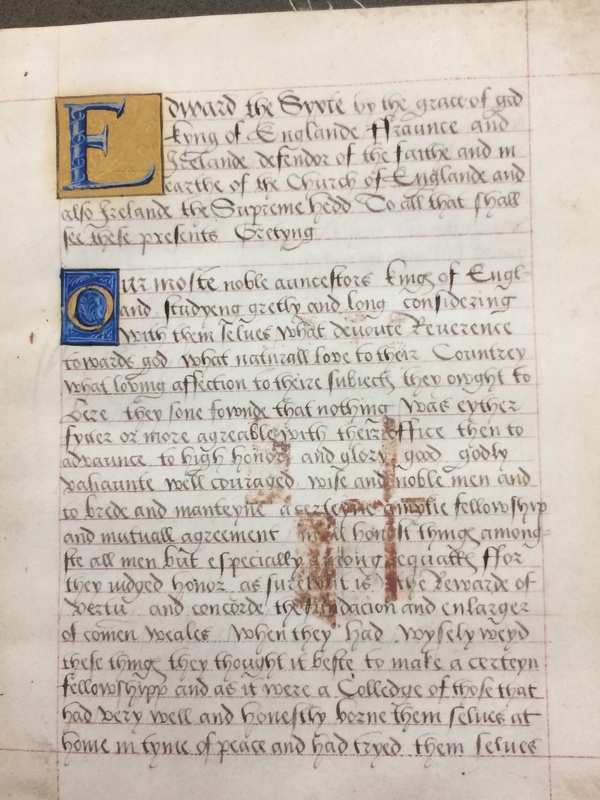

Illuminated Frontispiece with the 1552 emblem of The Order of the Garter. (MS Brown Eng 1 - Special Collections, University of Victoria)

Frontispiece

What's in an Emblem?

In his Art of English Poesy, George Puttenham firmly links the illuminated emblem, the Greek "emblema" or Italian "impresa", to embroidered textiles: the illuminator or artist "[puts] into letters of gold and send[s] to his mistresses for a token, or cause to be embroidered in escutcheons of arms, or in any border of a rich garment to give by his novelty marvel to the beholder" (191). There are two emblems contained within (and without) our physical manuscript. There is the first emblem we encounter, a pastiche of representation, that combines a now defunct Order emblem with an old form of textile art created in the modern era (or likely post-Victorian era); the second emblem we encounter is the frontispiece opposite the beginning of the text. It is also of the now defunct emblem, but is an authentic and original component of the manuscript. The emblem combines the arms of St George, the patron saint of the Order of the Garter, with the arms of the King of England. It seems fitting that the modern day emblem only contains the arms of St George. As the King shuffled off his mortal coil, so too did his emblem. The frontispiece is indeed a marvel to the beholder, but the marvel is tarnished by the degradation that has occurred.

Tarnished and Tethered Images

There is a strong connection between image and text. The earliest images were the only way to convey information, and even as humanity developed written systems of communication, they often remained indelibly linked to the drawn image (Egyptian hieroglyphics, Mandarin hanzi, or Japanese kanji). In the west we moved further away from these systems of communication, but not as much as we often presume. In Pens and Needles, Susan Frye discusses this link: "[c]onnecting language to some kind of picture, even the calligraphic drawing of the words themselves, enhanced connections to the world's complex truths through the multivalent play of signifiers" (Frye 4). For Frye it is in the emblem that we may see "the intersections of the visual and the verbal also connect[ing] everyday activities to representation" (Frye 4). It seems inevitable then that emblems and images will always hold considerable power over our imaginations.

This image is not only representative of concepts and symbols, but also of physical materiality. In a fashion, we may read this emblem by considering current and former material states. The current frontispiece is damaged, or degraded, due to the chemical makeup of the ink. The black tarnish on what would normally be the white arms of St George is likely due to the incorporation of silver in the original ink. The degradation was manufactured, or coded, into the structure of the emblem. The emblem was always going to eventually look like this, and not as the illuminator intended. If we step back and modify our reading, we can link the physically degraded state of the current image to the symbolically degraded state of the emblem. The emblem certainly has a historical meaning, but has been rendered meaningless by history and the passage of time. This degradation was also coded into the manufacture of the manuscript, through the events that would occur after the death of King Edward. If we go further we can read this emblem symbolically with the arms blackened and degraded state perhaps indicating the degradation of that iteration of the Order, or even of the representative notion of any Order. At the end of this thread of thought, we can see that it is only the arms of St George that are tarnished, perhaps even metaphorically reading this as representative of a tarnished England - of a degraded nation state. This might be an over-extension of the meaning tied up in this emblem, but it is an interesting exercise in the consideration of impressions that imbue a physical symbol such as this.

The first page of text in the Statutes. Of particular note are the decorated capitals and the ink transfer from the frontispiece. (MS Brown Eng 1 - Special Collections, University of Victoria)

The first page of text in the Statutes of the Order of the Garter (1552).

"Edward the Syxte by the grace of god

kyng of Englande ffraunce and

Irelande defendor of the faithe and in

earthe of the Church of Englande and

also Irelande the Supreme hedd To all that shall

see these presents Gretyng"

Ghostly Images

"In medieval manuscripts, the large initial capital letters may be elaborately decorated, but they still constitute part of the text itself, and we are challenged to appreciate the integration of text and image" (Bolter 12).

Even more than this, the first page of text forces continued consideration of textual materiality, and the interplay of past and present. Far from moving away from the communicative image, in the decorative capitals we are forced to negotiate the multi-valent meaning of image and text, all in one letter. Just as means of communication are troubled, so too is a sense of static historic chronology. As Susan Frye elucidates, quoting Maurice Merleau-Ponty: "Because our separation from the objects of the past is experienced through the thickness of the look and of the body,: a separation that is the essence of the experiencing both the body and the things, "this distance is not the contrary of this proximity, it is deeply consonant with it, it is synonymous with it". Viewed in this way, subject and object do not form a dichotomy but are partially integrated terms, although not terms in which the separation of the material object and the knowing body can be ignored. Instead for Merleau-Ponty, the separation of subject and object is itself the means of experience: "the thickness of flesh between the seer and the thing is constitutive for the thing of its visibility as for the seer for her corporeity; it is not an obstacle between them, it is their means of communication." In other words, the barrier between subject and object itself provides the means for two-way communication between the body and the world outside" (Frye 28). In the first paragraph of the manuscript we have King Edward VI speaking through his damaged missive across the centuries to greet us. It may not have been intended for modern readers, but that is, nonetheless, the unintended consequence of manufacture. The object ultimately has some form of strange agency that we can only wonder at.

Further down this page we can see that the frontispiece has left its mark on the accompanying page of text. Despite what one might assume from the deterioration of the emblem, it is not the black/white fields of St. George that stain the Statutes text, but the red cross of St. George and the red field of the Kings arms. Here we have an amplification of the interplay that is present between image and text - it is quite literally an unintended consequence that stems from the very physical nature of the text. Not only that, but the stain appears as a Christian symbol linked with suffering and blood, seemingly inviting other modes of understanding this stain. It is as if the manuscript is inviting our interpretations, and in this blood-red cross we can see the death of King Edward, the execution of Henry and Lady Jane Grey and countless others, and the considerable violence surrounding the Reformation. As Susan Frye says, "our perception of objects may encompass more than simply perceiving them in the present" (Frye 28). The religious struggles that would follow in the coming years are reflected in a physical stain in a manuscript written by a dead Christian king.

A 1549 iteration of the Statutes of the Order of the Garter. (By UnspecifiedUnspecified [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons.)

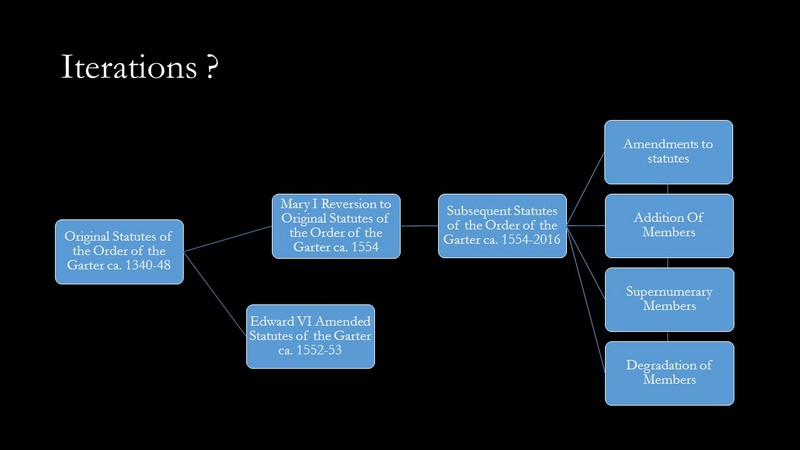

A diagram showing the linear progression of different iterations of Statues of the Order of the Garter. The proliferation of Statute iterations is due to the supernumerary membership and changes in the Statutes over times. Of particular note is the apparent disconnect between our iteration and the subsequent iterations.

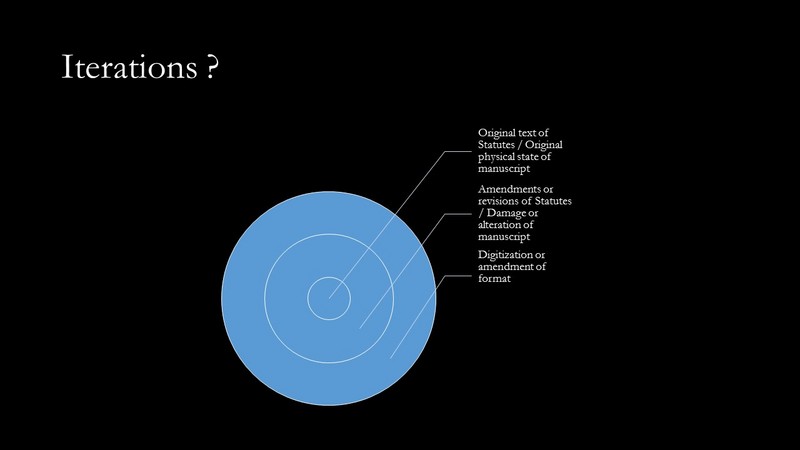

Category relations of iterations of Statutes of the Order of the Garter.

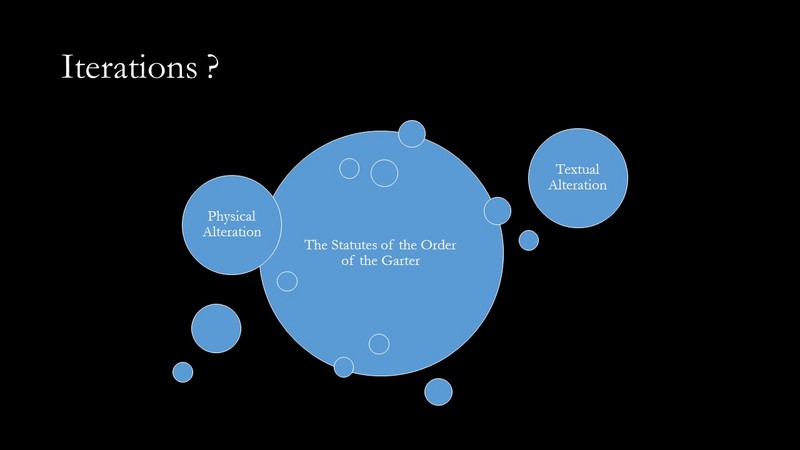

Constellational relations of iterative states of Statues of the Order of the Garter.

Reproduction, Regeneration and Dimensions of the Real

The 'Book'?

Working with this unique and beautifully troubling manuscript has forced me to consider the "book" in a number of different ways. Can this manuscript be thought of as "the" book, or "the" Statutes of the Order of the Garter? It is certainly the only MS Brown Eng 1, and it is most certainly "a" book, but like many books, this book is not as it initially appears. Consider the beautifully embroidered cover. Is the cover of a book "the" book? Is it merely a part of the book? Or is it not of the book at all? In this instance, the cover was not originally a part of the book. Does this mean it is not the book, or of the book? Although the embroidered binding is additive (maintaining use and adding beauty) it detracts from the authenticity of the manuscript. It elides an exact perception of the book by altering our reception of the material. However, this elision of history is inevitable - if we do not alter the book, the book will alter itself. Indeed, the book has altered itself through chemical and historical changes and has altered its own narrative. Through degradation and disintegration the materiality of the book is always in flux and our interventions are part of that conversation - a chronological material discourse.

This book was created at the request of King Edward VI. Within a year he would be deceased and his amended Statutes would be abolished. This places the book in a strange situation. It is a book containing information that is no longer relevant - information that lacks purpose or meaning. Is the book the text contained within? If we "[look] back from the perspective of our own time, when the word has been dissolved into an electronic code and copies are cheap and plentiful, it is difficult to appreciate fully the way the text itself could have value beyond the words it contains" (Deibert 50). Or is the book, instead, the information contained within? Or is the book just one of many similar books, one of a group of texts? Is it an object that is more readily defined by a locative position within a category? In the images to the right we see a similar, relatively contemporaneous Order of the Garter in an original velvet binding. It may be more authentic, but it is lacking something MS Brown Eng 1 possesses. There are many iterations of the Statutes of the Order of the Garter but are any of them more authentic? Is value determined by authenticity, age, or any number of other ephemeral qualities?

As seen in the discussion of the frontispiece, time affects everything. It ravages, degrades, and damages. In the frontispiece this is visible in the tarnished arms of St. George. The change was already occurring when the illuminator mixed his ink. It was always going to decay - to degrade. We can also see this process occurring in the staining on the accompanying page. All physical items are subject to entropy. Every manuscript, every printed book eventually becomes damaged, and often in ways that can never be foreseen. Many archives and libraries are attempting to combat this inevitable process through the use of digitisation, thus creating new cycles and processes of which we can only imagine. There is a modern conceit that digital technologies have somehow freed us from this endless cycle: "This revolutionary means of translating information is superior to older (analog) systems primarily because when information is translated into binary numbers, an infinite number of copies can be made without any degradation having occurred" (Deibert 124). This does not stand up to close scrutiny however, as the very act of transformation into a digital state is a translative, and thus, a degradative act. The very act of digitisation makes ideological presumptions about value and then ignores those presumptions. That does not mean that it is an inherently negative act, but that it is selective in assumptions surrounding the criteria that are valued.

Digitisation is an intervention with the past, an alteration, not a copy. A copy is ultimately an impossible notion, as it would only be a 'real' copy if it contained all that was contained in the original. The digitising process does not enable access to those qualities that are not valued by the digital: "other elements appear in the real encounter with a volume that were, often, purposely, discarded from the digital object: stains, notes, inserts, doodles, etc" (Cazes and Huculak). So is digitisation ultimately a dead end? Is the creation of a digital facsimile, edition, or version a textual dead end? MS Brown Eng 1 certainly is a dead end - of sorts. It contains the abolished amendments of a deceased king in a tactilely and visually beautiful anachronistic binding. Are the other subsequent Statutes even related? Or does each new copy, or iteration, supersede the one before? Does iterative distance allow us to apprehend the object in ways that allow a different experience, a new method of understanding?

Is it easier to think of these books as categories? The original, long-lost statute and the original manuscript states occupying a central position, with newer, altered, damaged, or digitised iterations occupying positions further from a central, or pure, state - a perfect Statute of the Order of the Garter. Or is it more precise to think of iterations of books as a sort of a constellation - with the perfect ideal of a book occupying a central position that exerts a sort of textual gravitational pull? Is this constellation even limited to iterations of any particular text? As Jay Bolter describes in Remediation: "Our culture conceives of each medium or constellation of media as it responds to, redeploys, competes with, and reforms other media. In the first instance we may think of something like a historical progression, of newer media remediating older ones and in particular of digital media remediating their predecessors. But ours is a genealogy of affiliations, not a linear history, and in this genealogy, older media can also remediate newer ones" (Bolter 55). As Bolter shows, the chronological discourse between iterations is unbelievably complex. The most interesting aspect of this remediation of non-digital and digital media is the fact that the manner of progression is analogue in form, not linear, not digital.

Digitisation forces us to contend with these issues in new and unforeseen ways. In Remediation Jay Bolter lays out a "double logic of remediation [that] can function explicitly or implicitly, and can be restated in [three] ways": mediation of meditation, inseparability of mediation and reality, and reform (Bolter 55). The first, mediation of meditation "depends on other acts of mediation. Media are continually commenting on, reproducing, and replacing each other, and this process is integral to media. Media need each other in order to function at all" (Bolter 55). But is this the case? Does the Early Modern manuscript need modern media? I would argue that it does need to be a part of the process. The alteration of the binding of MS Brown Eng 1 is just such a remediation. It intervenes in a manner that allows continued function. Bolter's second example, the inseparability of mediation and reality, posits that "[a]lthough Baudrillard's notion of simulacrum and simulacra might suggest otherwise, all mediations are themselves real. They are real as artefacts (but not as autonomous agents) in our mediated culture" (Bolter 56). In this way we can see that the new binding is itself a real artefact, it has additive value. Not only that, in his final example of remediation we see ""[r]emediation as reform", in which the goal of remediation is to refashion or rehabilitate other media. Furthermore, because all mediations are both real and mediations of the real, remediation can also be understood as a process of reforming reality as well" (Bolter 56). So, the additive binding can be understood as the real Statute of the Order of the Garter as much as any iteration. In fact, all iterations can be understood in this way, not merely a constellation, but a complex ecosystem of Orders of the Garter.

Is the process of digitization an additive remediation? Do any of these iterations obviate the need for an original manuscript? Are we preserving by copying? As I explain above, I believe that no digital copy is a veritable copy. It is always lacking in some manner, though this is not to say that these "copies" have no value. They are not "copies", they are simply new iterations: "[a]wareness of the multiple perspectives and layers of the pre-digital items ensures the freedom of the digital world, which is necessarily built on assumptions and reductions (as anything that is built): when one recognizes categories and choices, one is able to form a judgement and to propose alternatives" (Cazes and Huculak). This idea forces us to consider the value of an "original", such as it is. Is there value in alteration, damage, and degradation? Is there valuable data encoded in the physical object that would be lost if the "original" was destroyed - such as chemical changes occurring in inks, or physical processes linked to aging: "Variations, specific conditions, even errors in the making, are always telling signs of a book's story, whereas variations in the code or deterioration of a file lead to the absence of [the] digital object and remain untold stories forever" (Cazes and Huculak). A "copy" would not retain this data, and even if it could there are many other data that would go unconsidered and unknown and would inevitably be lost: "the transformation of books, manuscripts, maps, archives and other textual artifacts into digital objects, necessarily, involved a displacement of values and perceptions: a virtual library is not the reproduction of a real library through another medium: it is a different type of library, altogether" (Cazes and Huculak). If we think of "copies" as simply being new "iterations", then the digital iteration is a new form. It is a new thing that does not supersede the value of the original, but instead compliments it. It is a new form, a new object, in a larger conceptual literary ecosystem.

This allows use to consider the ultimate value of an original manuscript. Use is integral to value. To preserve books, or have others consider the preservation of books as a worthwhile endeavour, we must use them. We must, ultimately, offer a reason for their existence that supersedes their existence as receptacles for text. The book is more than that, much more. It may seem counterintuitive, but I believe that in addition to all the common methods of book preservation must be added - use. We must use books and handle them. We must risk damaging them, and when they have been damaged to alter them. If we do not, then the book fails to serve its purpose and becomes inert - meaningless.

The Knights and their Coats

Knights of the Order as listed in the Statutes on the last page of text, images below:

(Identification of individual knights as listed below was originally researched by UVic students Sydney Terepocki and Luke Oldfield. In instances where no known or available images were accessible, associated images have been substituted. All bibliographical information is paraphrased from Encylopedia Britannica Online.)

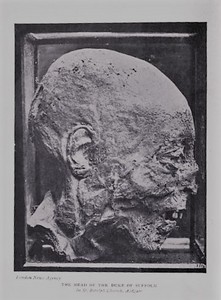

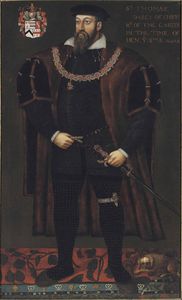

Henry Grey - 1st Duke of Suffolk, 3rd Marquess of Dorset

This is an image of a severed head found in Holy Trinity Church in London from Bell's Unknown London. According to Walter Bell, the head was found buried in oak sawdust in a vault. Sir George Scharf examined the head in the late 19th century and believed it to be that of Henry Grey. The acidic tannins from the oak preserved the head in remarkable condition. It is thought that it may have been hidden by the Widow Grey to prevent it from being displayed on the London Bridge. The head now resides in St. Boltoph's Church in Aldgate. (image from internet archive)

History

Henry Grey joined the Order of the Garter in 1547. He was a strong advocate of the Protestant faith and the father of the 'Nine Day Queen', Lady Jane Grey. He was beheaded by Queen Mary I on February 23 1554. The execution was carried out as a result of his collaboration in a plot to overthrow the Queen because of her decision to marry King Philip II of Spain.

William Parr - 1st Marquess of Northampton, 1st Earl of Essex and 1st Baron Parr

Sketch of Parr

This is a sketch in chalk and ink made in preparation of a portrait by Hans Holbein the Younger. To the left of the image of the Marquess can be seen the word 'MORS' (death). (By Hans Holbein the Younger [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

History

William Parr was the beloved Uncle of the young King Edward VI and brother of the Queen consort Catherine Parr. Parr was one of the primary advocates for Lady Jane Grey's short lived and disputed ascension to the throne. On the ascension of Queen Mary I he was sentenced to death, but then released shortly after. All titles removed by Queen Mary were restored to him by Elizabeth I.

John Dudley - 1st Duke of Northumberland

Dudley painting

Oil painting. Unknown artist. ([Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

History

An admiral, general, and politician who led the government during the reign of Edward VI. Dudley instituted nationwide policing by appointing Lords Lieutenants. He was an advocate of the English Reformation and supported government movements toward Protestantism. On Edward's death he marched on Mary but found that the Privy Council had sided with the Catholic Queen. Soon after his conviction he found renewed belief in the Catholic faith, but it was to no avail and he was executed in 1553.

Henry FitzAlan - 19th Earl of Arundel

Image of Henry FitzAlan

This is a reproduction of a painting of Henry FitzAlan from the National Portrait Gallery in London. (By Thomas Pennant [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

History

An astute and opportunistic politician, Henry FitzAlan successfully negotiated the treacherous political events of his life with considerable skill. He maintained a place of prominence throughout his life, and was one of few courtiers to do so. He was named for his godfather, Henry VIII, who was present at his baptism. He became a page in the court of Henry VIII at the age of 15, and attended the trial of Anne Boleyn. FitzAlan was amassing considerable poliical influence, until the coronation of Edward VI and the rise of the Seymour family saw his fortunes diminish quickly. Initially a supporter of the succession of Lady Jane Grey, upon Edward's death he immediately rode to Mary's side with the Earl of Pembroke to assist in her proclamation. His position at court improved considerably with Mary I and he was named Lord Steward of the royal household. Due to his considerable political influence, Elizabeth refrained from taking action against FitzAlan. Though he was involved in numerous machinations against the Elizabethan court, he was never subjected to anything other than house arrest.

Edward Stanley - 3rd Earl of Derby

Sketch of Edward Stanley

Chalk and ink drawing of Edward Stanley by Hans Holbein the Younger. (Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/1498–1543) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

History

Edward Stanley was raised principally by King Henry VIII and Cardinal Thomas Wolsey. In 1530 he accompanied Wolsey on his trip to present Pope Clement VII the declaration of Henry VIII's divorce from Catherine of Aragon. His first marriage, to Katherine Howard, ended after only a few weeks upon the death of his wife. He was then quickly married to his widow's aunt, Dorothy Howard. He was involved in numerous actions quelling rebellions during the reign of Henry VIII, and upon the succession of Edward VI he was raised to the Order. He maintained his good standing with all of Henry's children and remained on the Privy council throughout his life.

Francis Hastings - 2nd Earl of Huntingdon

Effigy of Francis Hastings

The alabaster tomb of Francis Hastings, located in St. Helens Church in Leicestershire. (By Andrewrabbott (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons)

History

The son of Henry VIII's mistress, Anne Stafford. Francis was created a Knight of the Bath in 1533. He was present at Edward's coronation and throughout Edward's reign he continued to have the confidence of royal inner circle. His considerable support for the succession of Lady Jane Grey led to his arrest and incarceration in the Tower of London by Mary I. His release in January 1554 was predicated on his success in locating and apprehending Henry Grey. He successfully located Grey and presented him to the Tower for execution. Though a staunch Protestant he remained in Mary's good graces until the succession of Elizabeth, due to beneficial family ties.

William Paulet - 1st Marquess of Winchester, Earl of Wiltshire

Portrait of William Paulet

Oil painting of William Paulet. (See page for author [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

History

Throughout his life Paulet amassed a considerable amount of political power. At one time or another he held almost all important political offices in England, such as: Comptroller of the Household, Treasurer of the Household, Master of the King's Woods, Privy Councillor, Lord Chamberlain and Steward of the Household, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal, and Lord High Treasurer to name just a few. He was a close friend of Cardinal Thomas Wolsey and Thomas Cromwell. He was present as a judge at the trials of Sir Thomas More and the accomplices of Anne Boleyn. He wielded considerable influence over the court of the young King Edward VI. After Edward's death he maintained his position in Mary's courtm and also saw favour in Elizabeth's court. He repeatedly professed for both the Catholic and Protestant faiths, always maintaining accord with the religious views of the sitting monarch.

William Herbert - 1st Earl of Pembroke

Portrait of William Herbert

Oil painting of William Herbert (By Unknown English: English School [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

History

Herbert was known throughout his life for his ferocious temper. In his early life he fled to France after killing a Mercer in Bristol. In France, he entered the service of King Francis I and distinguished himself as an exemplary soldier. Upon recommendation of King Francis, he entered King Henry VIII's service. In honour of his excellence of service, Henry bestowed numeorous properties including Cardiff Castle. His wife Anne Parr was sister to Catherine Parr, Henry's sixth wife. After the death of King Henry, Herbert was made guardian of the young King Edward. Though he was tightly bound by marriage to the Grey family, upon the succession of Mary, he threw his daughter-in-law Catherine Grey out of the house. He obtained further favour with the new queen by destroying the Wyatt Rebellion. Like other astute personages of the time, he would bend with whatever religious whims the new monarch held dear. Though professing to be a devout Catholic in Mary's court, he immediately expelled the abbess and nuns from Wilton Abbey upon Elizabeth's succession.

Walter Devereux - 1st Viscount Hereford, 9th Baron Ferrers of Chartley

Image of tomb of Walter Devereux

Effigy of Walter Devereux and his 2nd wife Margaret Garneys located in the Church at Stowe by Chartley. (by cdevere1 (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

History

Devereux fought in many of the conflicts of his time in places such as Cambrai and Italy. His actions in a naval battle off the coast of Brittany led to the honour of membership in the Order of the Garter. Throughout his life he fought with the powerful Welsh landowner Rhys ap Gruffydd. With Rhys' execution for treason in 1531, Devereux was free to assume local power in Wales.

Edward Clinton - 1st Earl of Lincoln, Lord High Admiral

Painting of Edward Clinton

Oil painting of Edward Fiennes de Clinton currentl displayed in the National Portrait Gallery in London. (See page for author [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

History

Clinton was originally knighted for his role in the capture of Edinburgh in 1544. He was commander of the English fleet in the war against Scotland in 1547. While Governer of Boulogne he succesfully defended that city against the French in 1550. From 1550-1553 he served as Lord High Admiral under King Edward VI, and later from 1559-1585. Clinton also assisted Pembroke in the destruction of Wyatt's Rebellion in 1554.

Thomas Cheney - Lord Warden of the Cinque-Ports

Grave of Sir Thomas Cheney

The burial effigy of Thomas Cheney at the Church of St. John at Minster on the Isle of Sheppey. (by Jorge (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

History

Cheney was a favourite courtier of Anne Boleyn, and an enemy of Cardinal Wolsey. From 1509, Cheney served five monarchs as Lord Warden and became the most powerful man in South-East England. He opposed Lady Jane Grey's succession to the throne, and supported Mary's cause for the crown. From 1536 onwards he held the post of Lord Warden of the Cinque-Ports and was responsible for coastal defense in the area.

Thomas Darcy - 1st Baron Darcy of Chiche, Lord Chamberlain

Painting of Thomas Darcy

Oil painting of Thomas Darcy attributed to Gerlach Flicke. (After Gerlach Flicke [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

History

Darcy held the positions of Vice-Chamberlain of the Household and Captain of the Yeomen of the Guard, and eventually ascended to the Privy Council and Lord Chamberlain of the Household. Due to his involvement as a signatory to letters proclaiming Lady Jane Grey as heir to the throne, he was imprisoned by Mary I, but was eventually pardoned. By the time of his death he had lost his offices, but retained his title which he passed on to his eldest son.

George Brooke - 9th Baron Cobham

Portrait of George Brooke

Chalk and ink portrait of George Brooke by Hans Holbein the Younger. (Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/1498–1543) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

History

In his youth, Brooke fought in France and later in Scotland. For his actions he was appointed as the commanding officer of forces garrisoning Calais. He entered the Privy Council in 1550, and after the death of Edward he supported Lady Jane Grey's succession. Though he was pardoned by Mary, he was related to the Wyatt family and feel under suspicion during the Wyatt Rebellion. After his imprisonment and subsequent release he ceased political involvement at a national level and returned home to Kent.

Andrew Dudley

The Good Ship Pauncey

This image is of the carrack Pansy (Pauncey) from the Anthony Roll. (By Own scan. Photo by Gerry Bye. Original by Anthony Anthony. [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

History

Dudley received a parliamentary commendation for his naval actions in the 'War of Rough Wooing'. On 7 March 1547, Dudley captured a Scottish principal ship The Great Lion with his own ship Pensée. All four Scottish ships surrendered and The Great Lion sunk while being towed to Yarmouth. For his capture of men and ships Dudley received considerable prestige.Upon his return to the north he captured Broughty Castle and was appointed Captain of the Garrison. Under Edward VI he was named to the Privy Chamber. In 1552 he was sent on a diplomatic mission in an effort to broker peace between Emperor Charles V and France. On Edward's death he raised 500 men to fight against Mary, but was soon arrested an imprisoned in the Tower. The day before his execution he attended Mass and because of this his life was spared. He was given a small annuity and allowed to retain some possessions.

William Cecil - 1st Baron Burghley, Chancellor of the Order of the Garter

Painting of William Cecil

Oil painting of William Cecil attributed to Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger. (By by unknown artist; attributed to Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

History

Cecil was one of the most important political figures of the Elizabethan age. He began his career in the service of the Duke of Somerset, and accompanied him on his forays into Scotland during the 'War of Rough Wooing'. In 1550 he became one of the two 'Secretaries of State' of the young King Edward VI. In 1551 he was appointed Chancellor of the Order of the Garter. He attempted to fight the succession plans of Edward VI, but saw that in doing so he was placing himself at considerable risk. He eventually relented and signed the document. He immediately moved to ingratiate himself with Mary upon learning of the death of Edward and avoided execution. During the reign of Mary I he found himself out of favour, but his fortunes changed with the succession of Elizabeth I. During Elizabeth's reign he worked for the unification of a Protestant British Isles, through the conquest of Ireland, and the unification of Scotland and England. He was elevated as Baron Burghley by Elizabeth in 1571.

Philip Hoby - Usher of the Black Rod

Sketch of Philip Hoby

Chalk and ink sketch of Philip Hoby by Hans Holbein the Younger. (Hans Holbein the Younger (1497/1498–1543) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

History

Hoby served as the English Ambassador to the Holy Roman Empire and Flanders. He served for a short time as a gentleman usher of the King's Privy Chamber, but was soon thereafter imprisoned for heresy. In 1552 he was appointed to the Privy Council. Though believed to have been a supporter of Lady Jane Grey he somehow maintained good favour with Mary I.

Gilbert Dethick - Garter Principal King of Arms

Image of Dethick painting

Facsimile from 1574 painting currently displayed in the College of Arms. (See page for author [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

History

Though Dethick claimed English descent, there is strong evidence that he was of Dutch origin. At the age of 16 he entered the College of Arms. He quickly rose through a number of positions to be named the Garter Principal King of Arms under King Edward VI in 1550. Dethick was one of the party sent to negotiate the marriage of Ann of Cleves to Henry VIII. He accompanied Lord Somerset in the 'Rough Wooing', and was often sent abroad on important diplomatic missions.

Sir Henry Grey

(By Rs-nourse (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons)

Sir William Parr

(By Rs-nourse (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons)

Sir John Dudley

(By Rs-nourse (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons)

Sir Henry FitzAlan

(By Rs-nourse (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons)

Sir Edward Stanley

(By Rs-nourse (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons)

Sir Francis Hastings

(By Rs-nourse (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons)

Sir William Paulet

(By Rs-nourse (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons)

Sir William Herbert

(By Rs-nourse (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons)

Sir Walter Devereux

(By Rs-nourse (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons)

Sir Thomas Cheney

(By Rs-nourse (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons)

Sir Thomas Darcy

(By Rs-nourse (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons)

Sir George Brooke

(By Rs-nourse (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons)

Works Cited

Bolter, Jay David, and Richard Grusin. Remediation: Understanding New Media, MIT Press, 2001.

"Bruce and Dorothy Brown Collection." University of Victoria Libraries.

Cazes, Helene, and J. Matthew Huculak. "Understanding the pre-digital book: 'Every contact leaves a trace.'" Doing Digital Humanities: Practice, Training, Research, pp. 65-82, Routledge, 2016.

Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, 2016. Web. 1 Dec. 2016.

"The Most Noble Order of the Garter." College of St. George/Windsor Castle, Dean and Canons of Windsor, 2008-16.

Deibert, Ronald J. Parchment, Printing, and Hypermedia: Communications in World Order Transformation, Columbia University Press, 1997.

Frye, Susan. Pens and Needles, University of Pennsylvania Press. 2010.

Marks, Philippa. "English Embroidered Bookbindings", British Library: Help For Researchers,

Puttenham, George. The Art of English Poesy, Edited by Frank Whigham and Wayne A. Rebhorn, Cornell University, 2007.

Terepocki, Sydney and Luke Oldfield. "Statutes of the Order of the Garter." Medieval and Early Modern Manuscripts, Special Collections, University of Victoria, 2015.

Works Consulted

Beltz, George Frederick. Memorials of the Most Noble Order of the Garter, from its Foundation to the Present Time, Pickering, 1841, Internet Archive, 1 Dec. 2016.

Nicolas, Nicholas Harris. History of the Orders of Knighthood of the British Empire, Vol. 1, Pickering, 1842, Internet Archive, 1 Dec. 2016.

Nichols, John Gough. Literary Remains of King Edward the Sixth, J.B. Nichols & Sons, 1857, Internet Archive, 1 Dec. 2016.

Pridaux, S.T. "Embroidered Book Covers, Materials, and Stitches," bookbinding.com, Denis Gouey Bookbinding Studio, 1997-2016.

Roskell, John Smith. Parliament and Politics in Late Medieval England, The Hambledon Press. 1981.

Trigg, Stephanie. Shame and Honor: A Vulgar History of the Order of the Garter, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012.

RC / Fall 2016