Paul Klee, On modern art (1948)

Contents

I. How to use this page

II. Introduction

III. Key Terms and Definitions

IV. The Art Book and the Book as an Im/Material Network

V. The Network and Modernism

VI. Further Reading

VII. Works Cited

VIII. Additional Scholarly Citations

I. How to use this page:

This resource has two layers. The first, in the brownish and larger text, is available for the browsing, casual, and curious reader. It provides an overview of the concepts and conversations that are a part of this resource.

✧✧✧

The second layer, in smaller black text, builds off the first layer, for the potentially academic (and still curious) reader. Although both layers are connected, they can be read either separately or together, at the reader’s convenience and preference. The intent of this layering is to provide a resource that, while guiding the reader through the author’s ideas, allows the reader to have a choice of how to access this resource, and a little more flexibility to interact with this resource at their own pace.

II. Introduction

This project is about texts, materials and networks. Its focus is the modernist artist Paul Klee’s On modern art (1948 [Über die modern Kunst 1945]). In 1924 Klee gave a lecture on modern art at the Museum in Jena (Germany), which was published in book form posthumously. To quote Klee, an investigation of On modern art requires “the knowledge that the thing is more than its outside reveals” (quoted in Sallis 16).

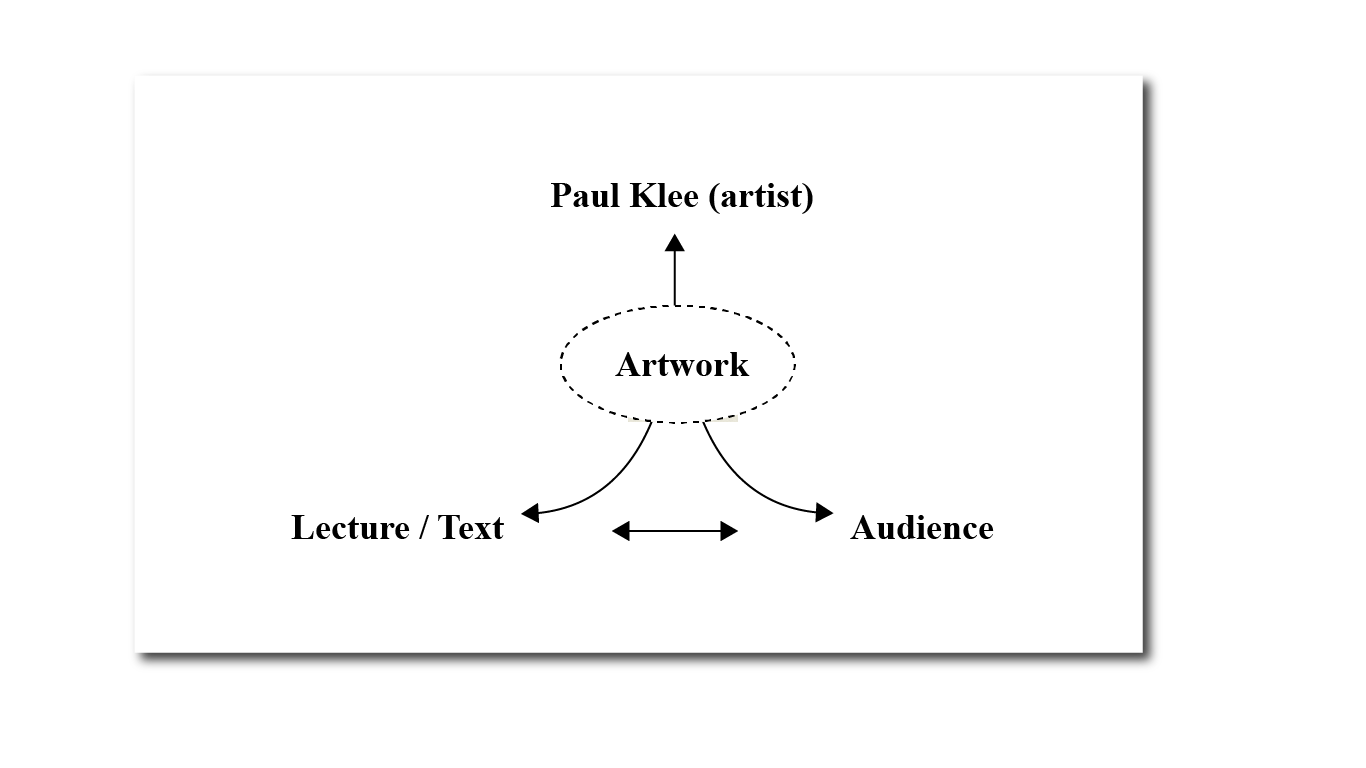

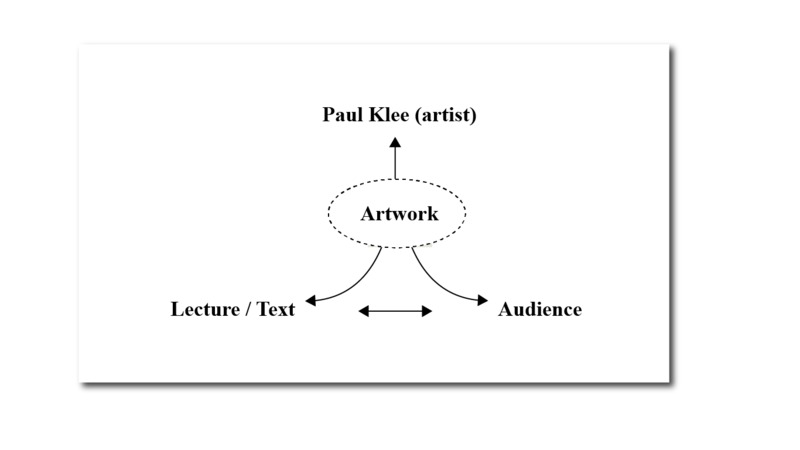

What then does this project set out to do? Its intent is to examine On modern art as one part of a network of media. This is a four-part network, as detailed in Figure 4 below. The four parts are as follows: the lecture in Jena and its textual form; the audience to both the text and the lecture; the artist Klee himself; the artwork, as both conceptual and material network. Klee’s On modern art is both part of a series of networks and a network itself.

There are three central arguments threaded through this page, to be kept in mind throughout but outlined explicitly and in full here. First, this analysis relies on Walter Benjamin’s “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility” (1936). The network itself is defined by its own reproduction in different forms that modify the effect of Klee’s lecture and his art. From the moment Klee finished an artwork, or the moment he ended his lecture, On modern art has not had “a unique existence in a particular place” (Benjamin 21), and the reproduction of this network has modified its effect. In order to consider the network’s reproduction, it is necessary to make a second argument: that this network is a medium, but it is a medium characterized primarily by mimesis and experience. This second argument relies primarily on another Benjamin essay: “The Storyteller” (1936). Because this network is a media, the third central argument details how a consideration of On modern art as a media network changes the nature of the text as an object. This change reciprocally alters the roles and relationships between all three central arguments: reproduction, media and object.

This page is divided into the following sections. First, I define key terms for my argument and expand on my conception of On modern art as a four-part network. Then, I look at the art book as an im/material network. The third section, entitled the network as modernism, examines just that: the ‘network’ from a modernist perspective, focussing on media and mimesis, and the ways in which Klee’s network can be assessed as a process of intermedia.

✧✧✧

We know that books are material objects. We can feel them in our hands, see them, even smell them. But books are more than just things. They represent relationships between people and ideas. The modernist artist Paul Klee’s On modern art (1948) is an interesting example of these relationships (see Figures 1 and 2). Its content, a lecture on modernist art, was initially addressed by Klee to an audience, at the Museum in Jena, in 1924. This lecture was later reproduced as a book. Because the lecture was reproduced as a book, it has (at least) two iterations. On modern art can be read as a network. The primary intent of this resource is to communicate how the reproduction of Klee’s lecture altered its meaning, and what that alteration of meaning says about networks, modernism, and media.

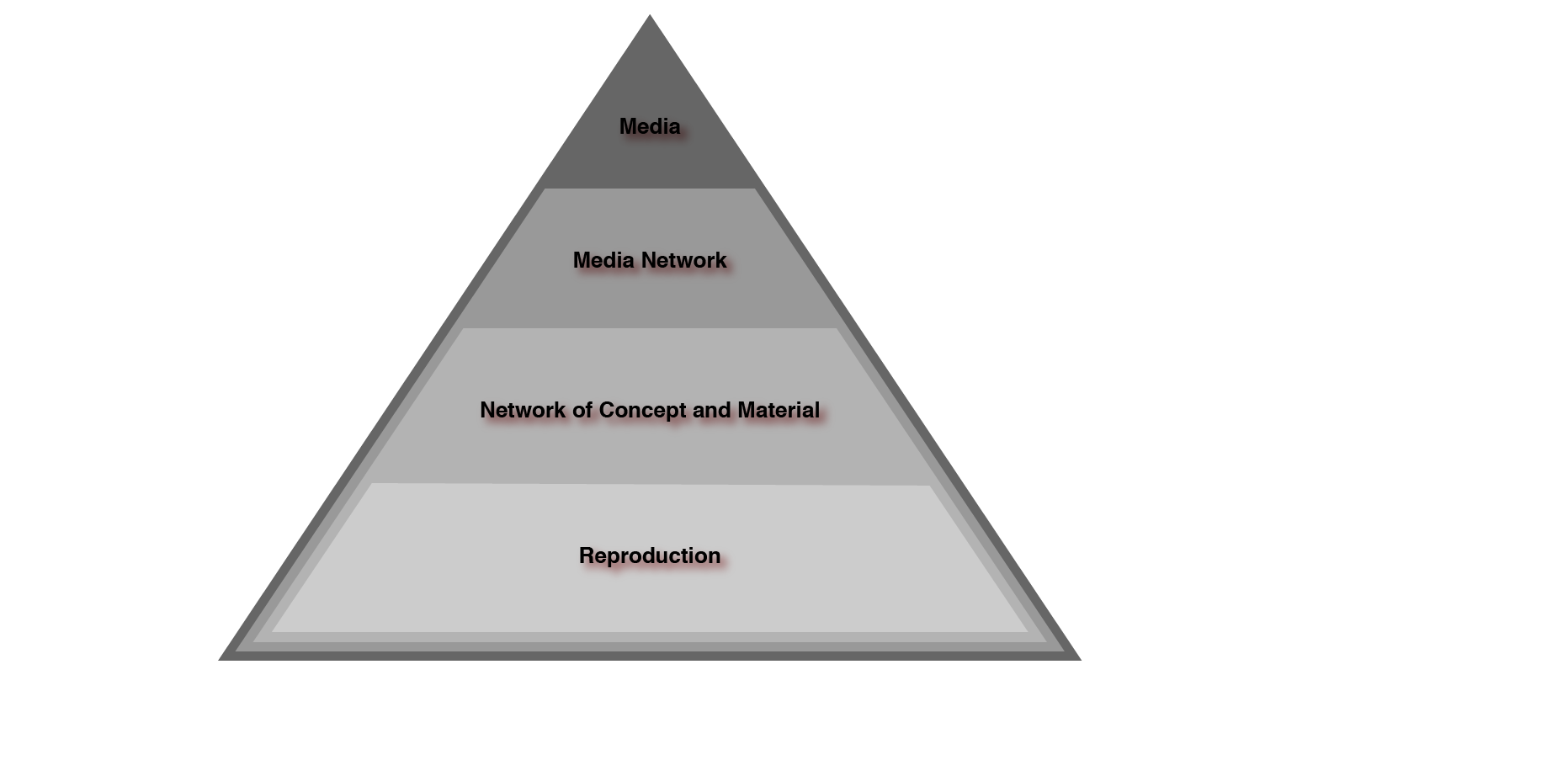

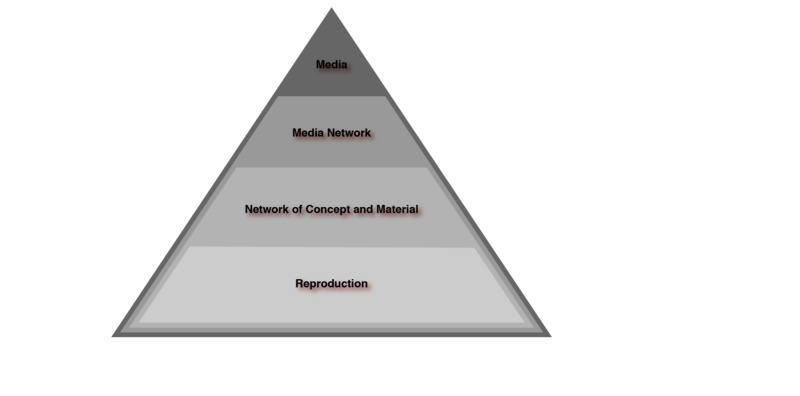

The following section, Key terms and the Network, provides a guide to terms and concepts used by this resource. Figure 3, also pictured immediately above this paragraph, shows the visual relationship between media and its constituent parts, as assessed with relevance to On modern art. We often take the medium for granted. But the medium is, in fact, a kind of infrastructure or apparatus too. It is a middle or an in between. This resource in large part focusses on the media networks that Paul Klee’s On modern art is a part of. Figure 4, also pictured immediately below this paragraph, is a visual aid for conceptualizing these media networks. I want to point out a network (and the network that I am referring to) is not defined as a static object but instead as interconnected, moving parts. This concept can be thought about by considering the provenance of a book. It might seem that if I give you, the reader, a book, that what was once mine is now yours. But there are more moving parts in this equation. Prior to either of our “ownerships,” this book was made: its pages were bound, and ink was transferred onto the material object to give it its content. Even before that, the content of the book was written, transferred from an idea into a text. In the case of Klee’s On modern art, the text of the book was initially addressed as a lecture some 24 years prior.

The central idea that is threaded throughout this resource, then, is that On modern art is more than an object: it is also a text whose nature has changed since its inception.

✧✧✧

Fig. 3. Conceptualizing Media; diagram created by SH

Fig. 4. Paul Klee's Four-Part Network; diagram created by SH

III. Key Terms and Definitions

What is a network? Alexander Galloway’s section on the network in Critical Terms for Media Studies provides a useful definition that provides a framework for this project:

The English term network is a compound formed from the Old Saxon words net, an open-weave fabric used for catching or confining animals or objects, and werk, both an act of doing and the structure or thing resulting from the act. (283)

[N]etworks are understood as systems of interconnectivity. More than simply an aggregation of parts, they must hold those parts in constant relation. (Ibid., emphasis added)

In particular, I’d like to focus on the idea that a network’s parts are “in constant relation.” At any given time after the publication of On modern art, all four of lecture/text, artist, artwork and audience are in constant relation. As a result, these four parts can be read as an interconnected network; but also the book itself is a network, because it is a form of doing, or a process.

It is critical for my purposes to recognize that a network is a set of media. It’s difficult to give media a static definition (as Critical Terms for Media Studies indicates in its introduction) but there are a couple of understandings I’d like to point to for consideration in this project. Colloquially, media can be thought of as the media (as in mass media) which is a means of communication. Although this definition implicitly makes reference to form, it nonetheless primarily defines media by its content. It is more useful to define media as Marshall McLuhan did in Understanding Media (1964), where the message (the content) is the media (the form) itself. Of course, this definition should not be thought about uncritically, or treated as a universal truth, but I think it provides a useful starting point in this case. For my purposes, I have chosen to assess Klee’s text not just for the content inside, but as a form that is media. On modern art is not only a content (in other words, an end or a node) that is part of a network, it is a media itself — a middle — that connects each node.

A network, as a system of interconnectivity, can be comprised of both concepts and materials. The concept has an intricate philosophical history that I won’t go into here, but it is useful to understand it as an “idea,” an “image” or a “mental representation [a thought]” (OED). For Klee himself, there is a bridge between concept and material called creation: “the artist's creation is never finished; it continues, just as it has ever continued before” (Sallis 103). It is critical to recognize that concept and material are interconnected as a network, and, moreover, that the concept doesn’t inherently determine the properties and realization of the material. The material does serve as a kind of antithesis to the abstract (the concept) insofar as it is superficially concrete, but that does not mean that it is separate from the concept (see Bill Brown in Critical Terms for Media Studies 49).

Interconnection of the kind Galloway defines as a network and that connects concepts to materials occurs in form; interconnection also implies a kind of activity. One term used to define this activity (that is central to this project) is reproduction. Reproduction is “the action or process of forming, creating, or bringing into existence again” (OED). For my purposes, reproduction is usefully defined in more depth by Benjamin’s “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility” (1936). Art — but also the ancillary network to art of the kind I have outlined in the introduction — is defined by its irreproducibility, or its uniqueness. A summary of Benjamin’s essay here is unnecessary (since his focus shifts onto the implications of technological innovations in film and photography) but one salient point emerges for this project’s consideration. The reproduction of art made possible by 20th-century technological advances modified the effect of art by disabusing the artwork as a singular entity from a “unique existence in a particular place [and time],” thereby changing notions of physical structure and ownership of an artwork (21). Benjamin was speaking primarily about the artwork, but his argument can be applied more broadly to the network outlined in the introduction. The nodes of this network, in their interconnection, reproduce and modify the effect of the central “artwork” located at the nodal midpoint. The genealogy of On modern art (from lecture to published text) means that Klee’s lecture, as a concept and as a material object, does not have a unique existence in a particular place and time.

Media, the media network, the network of concept and material, and finally, reproduction exist as a kind of pyramid. In this context of Klee’s work, at the top is the abstract media network, a kind of meta-structure that may be separated into ontological sub-categories of the conceptual and material. These different understandings of the network, as interconnectivities, are defined by the abstract idea of reproduction, or their reproducibility. Without diving too deep into media studies itself it is critical to recognize that the network is a kind of process. Process implies movement and therefore network categories do not exist in isolation (since they are interconnected). Process can be defined succinctly as “going on, continuous action, proceeding” (OED).

If the network involves reproduction, and both the network and reproduction, as media, are processes or actions of interconnectivity, it is useful to delineate what I want to examine about their nature in the context of Klee’s On modern art. The key term here is mimesis. Mimesis is imitation, but in this context, specifically “the representation or imitation of the real world in (a work of) art, literature, etc.” (OED). In Klee’s network, the reproduction of his lecture in text form is a kind of representation of both the artwork and the artist, the conceptual and the material: it is a mimetic reproduction that ‘modifies the effect’ of the network.

Fig. 5. Sleep, 1914. In On modern art.

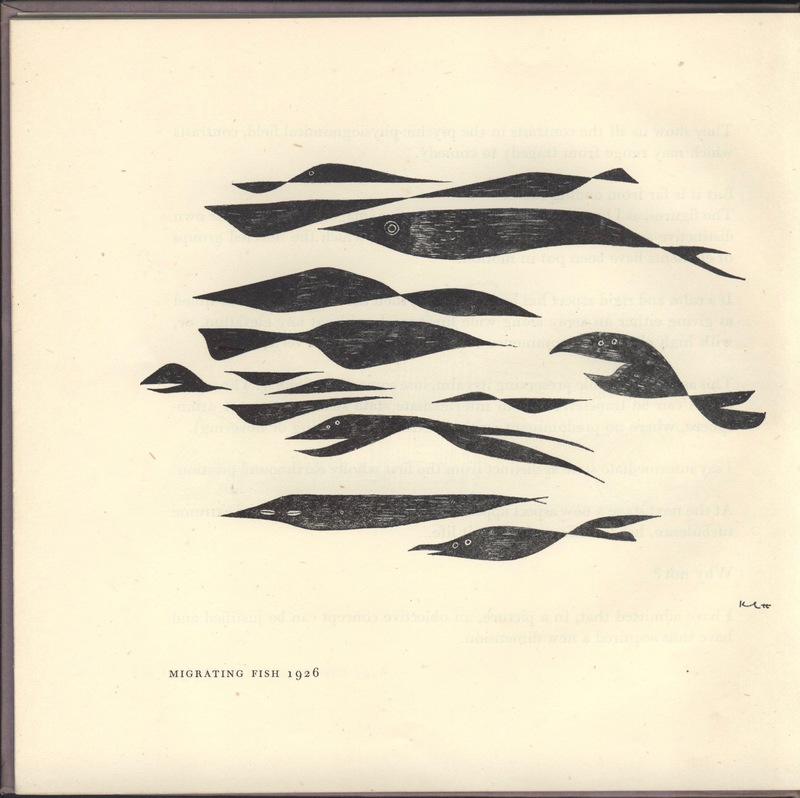

Fig. 6. Migrating Fish, 1926. In On modern art.

Fig. 7. Herbert Read, 1966

✧✧✧

The previous section suggested that Paul Klee’s text could be read as a kind of middle: a text whose nature has changed across various iterations, from a lecture at a Museum to a book in Special Collections at the University of Victoria. In fact, On modern art is not in Special Collections because of Paul Klee; instead, it is at UVic because of Herbert Read. Who was Herbert Read? He was a modernist art critic, and he wrote the introduction for the English version of Klee’s text. Special Collections has his archive. On modern art was catalogued on February 8, 1979, likely because academics at the University purchased it in an effort to expand the Read archive. Heather Dean, the Associate Director of Special Collections, indicated to me that little else is known about how the text came to UVic (email, November 6 2018). The presence of On modern art at UVic makes Special Collections another node in the network surrounding this text, and UVic is, in a way, interconnected with the lecture that Klee gave as far away in time and space as Jena in 1924.

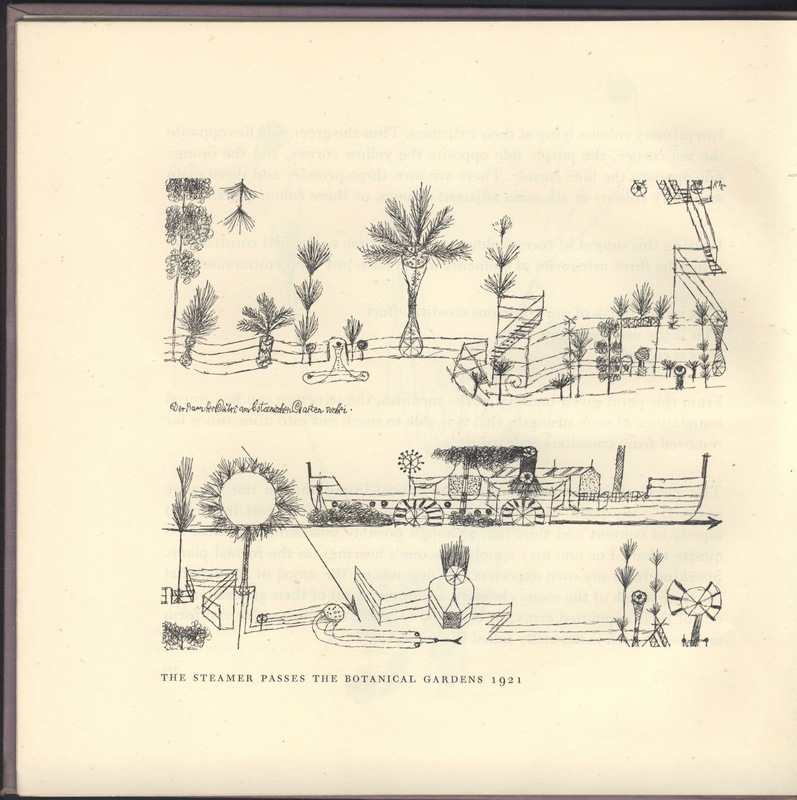

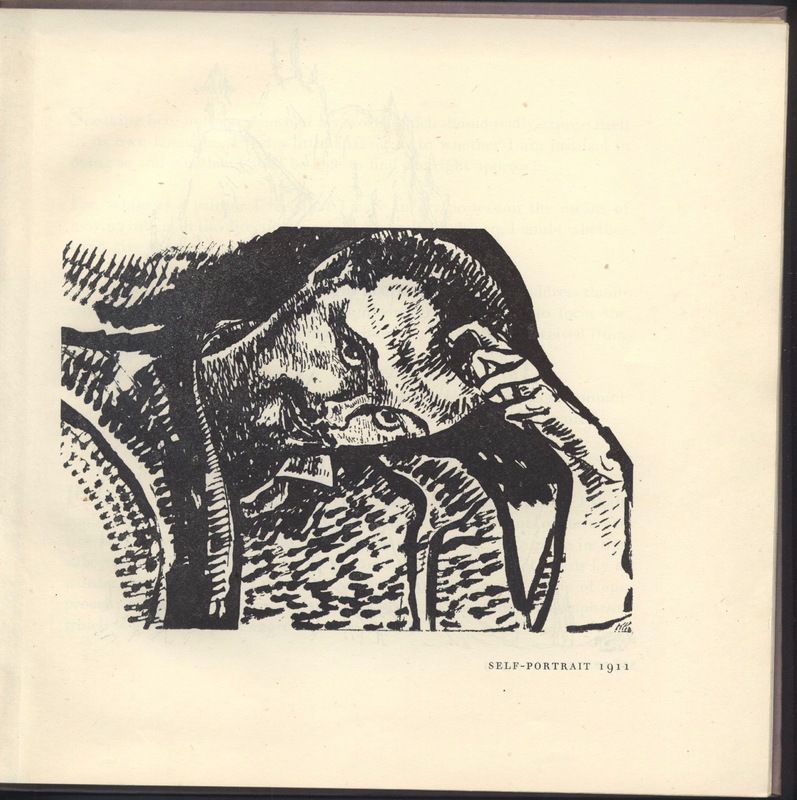

I would like to pause for a moment to consider how UVic is interconnected with Klee, and what that interconnection says about preservation. Special Collections, as an archive, preserves material objects, often in the form of books. But it would be reductive to suggest that what is preserved is only a material “thing.” On modern art is a text that has changed over time and space: it is a network not only of textual iterations but also of ideas from Paul Klee and about Paul Klee. This text contains reproductions of some of Klee’s drawings, that were conceptualized at one point in time, before then being drawn and later reproduced in the book. Some of these drawings have now been scanned, in Figures 5 through 9. What these reproductions and changes mean, for the preservation of not only On modern art but also the network around it, is that it is impossible to isolate On modern art in a time or a place. Even if this text sits in your hands, as you sit in Special Collections looking at it and thinking about it, On modern art is more than just that moment with you.

✧✧✧

Fig. 8. The Steamer Passes the Botanical Gardens, 1921. In On modern art.

Fig. 9. Self-Portrait, 1911. In On modern art.

IV. The Art Book and the Book as an Im/Material Network

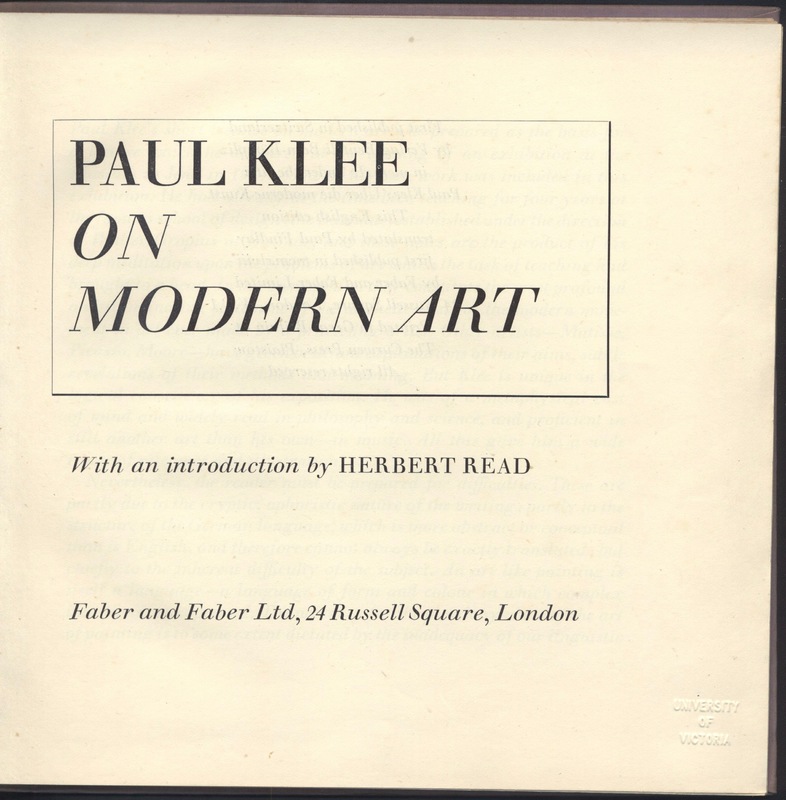

On modern art was not a book. Its text was instead a treatise on modern art prepared for a lecture to be delivered at the opening of an exhibition at the Museum in Jena in 1924 (see the introduction). It was not published until after Klee’s death in Switzerland in 1945 (Über die modern Kunst). The edition I worked with was published by the modernist press Faber and Faber in an English translation in 1948 and is introduced by the modernist art critic Herbert Read. Read calls Klee’s lecture a “cryptic, aphoristic” statement on the “aesthetic basis of the modern [art] movement” (7), while still noting the lecture’s importance to modernism. The actual content of Klee’s lecture/text is less important here than the book itself, since this is not a project about the aesthetic bases of modern art. Instead, I focus on the formal and material manifestations of On modern art.

There are a number of points that can be made about the form of the content of On modern art. It existed first in oral form, as a delivered lecture. The delivered lecture at Jena was received by an audience, which gave the lecture the property of a medium. In fact, this lecture connects the network this resource investigates for the first time: this lecture is its first temporal existence, or its “unique existence in a particular place” (Benjamin 1936: 20). The lecture connected audience and artist (Klee), while the ephemeral cloud of art (and of Klee’s artwork) hung over it. The lecture existed largely in conceptual form, since Klee’s oratory performance did not include materials. It made reference to art — and to artworks as materials — but did not ‘contain’ material as a part of its essence. Because the lecture as an oral form could not be, literally and materially, Klee’s artwork, art and Klee's own work existed more as an ephemeral cloud, or a kind of medium.

The nature of On modern art changed, however, when it was published in the form of a book. The publication of a text previously delivered as a lecture by definition required a reproduction of that lecture in textual form. This reproduction meant that the conceptual form of the lecture now existed in material form: the book. The medium shifted from oral to textual within this reproduction, and no longer had “a unique existence in a particular place” (with reference to Benjamin): its effect was modified, and therefore the network itself was modified.

Before following the argument about reproduction, it is valuable to digress briefly into a few notes on the book as a material object, since Klee’s lecture was reproduced in codex form. What’s perhaps most interesting about Klee’s text is that it is decidedly unremarkable. The material book is a thin square. Its shape is not a traditional rectangle, nor is there any immediate indication of the book’s content. We know that a modernist press like Faber and Faber wanted its books to “appeal to the eye and touch as well as to the mind of the reader” (Rose and Anderson 115). It’s likely that Klee’s book would have had a jacket, lost at some point in time. Nevertheless, why a small, square and unassuming book when it contains, according to Read’s introduction, “the most profound and illuminating statement of the aesthetic basis of the modern movement in art ever made by a practicing artist” (On modern art 7) as well as a not insignificant number of Klee’s own reproduced drawings? Is the form of Klee’s text instead explained entirely by its posthumous publication? Finally, why publish and print an art book so soon after WWII?

These questions don’t necessarily have concrete historical answers, but it is nonetheless possible to use them as an entryway into a discussion on reproduction, which exists as an attempt at filling in the lacuna between what On modern art is as an object in a network, and what that existence means. What is an art book, and how does it differ from On modern art? Thankfully, Klee’s text is not burdened by a finite definition as an art book, even though the artbook is the “quintessential 20th-century artform” (Drucker 1). Johanna Drucker’s survey and investigation of this quintessential form (The Century of Artists’ Books 1995) is valuable as citation here, particularly since Drucker focusses on the variability of the art book as form (1-10). It is therefore possible to define On modern art as an art book since there is no burden of norm bounding the text to a static definition, witnessed in the claim that Drucker immediately repudiates that “an artist’s book is a book created as an original work of art, rather than a reproduction of a pre-existing work” (1). At the same time, Klee did not publish this text; he gave a lecture some 20 years prior. He is the sole author of the book’s content at the same time as he has no authorship over the codex as a form. Drucker’s question about what makes a work of art “original” (1) is pertinent. I do not intend to answer this question, since the attribution of provenance is an “approach to history [that] is hopelessly beleaguered by…founding fathers” (8) and a teleological historiography. Recall, from the introduction, Klee’s assertion that “the artist's creation is never finished; it continues, just as it has ever continued before” (Sallis 103). In sum, what is important about On modern art is that Klee’s authorship — in terms of its originality — does not really matter. The book is an art book by virtue of its ability to “draw upon a wide spectrum of artistic activities, and yet, duplicate none of them” (Drucker 10). What matters about On modern art is that it is a network of reproduction, of an immaterial concept (in the form of a lecture) into a material object (the book).

To trace this network of reproduction, from immaterial concept into material object, it is useful to consider how the book preserves and what preservation means. Here I turn to Lisa Gitelman’s Paper Knowledge (in particular its first chapter): “[w]riting is mnemonic, the history of communication tells us; it is preservative” (22). In this resource, I am arguing that On modern art preserves not only the concept of but also the content of a lecture; it does not, however, preserve what we might call the lecture’s form — the act of the lecture itself, its delivery and enunciation and the setting where Klee stood and delivered his words to an audience. While a surface reading of Klee’s text would connote absolute preservation (which, in the case of the content of the lecture, is true) a deeper reading would argue that the network of communication that took place in the Museum at Jena has not been preserved. Instead, this network has been reproduced and, critically, this reproduction has, in Benjaminian fashion, modified its effect. The preservation of the concept as the book is also the preservation of the network itself, in the form of its modifying reproduction. There has been a material reproduction of Klee’s lecture; there has also been an immaterial reproduction of the network. There is no “unique time and place” to On modern art. The text — in both its codex form and its earlier lecture form — cannot be isolated, either as an “original” im/material entity, nor as a network defined by a teleological provenance. Instead, for my purposes, the text is most usefully thought of as a form of change. Change has a connection to modernism: the era and idea that Klee lived within. The next section develops my discussion of network reproduction and change into a digression on (inter)media and mimesis.

✧✧✧

This resource has argued that On modern art can be defined by its changes and networks of interconnection. Although modernism was defined by many different (and sometimes disparate) characteristics, it can be understood as a response to changes in world-historical processes, like industrialization and urban growth. There is, therefore, space, in this resource, to argue that the history of On modern art as a network has parallels to modernism itself. (See Figures 9 through 11 for examples of Klee’s text as a document that argues for modernism, as well as The Network and Modernism.) These parallels could be serendipitous, or they could be intentional, since Klee himself was a modernist, as was Herbert Read, the writer of the introduction. What is perhaps most exciting about these parallels is that change, for lack of a better expression, can be difficult to put one’s finger on. That change, and the questions it raises about preservation and the very existence of On modern art, are what make not only Klee’s text, but also the many texts in archives and libraries around the world, worthy of study.

✧✧✧

Fig. 10. Title Page of On modern art with Introductory and Publisher Accreditation.

Fig. 11. Herbert Read's Introduction.

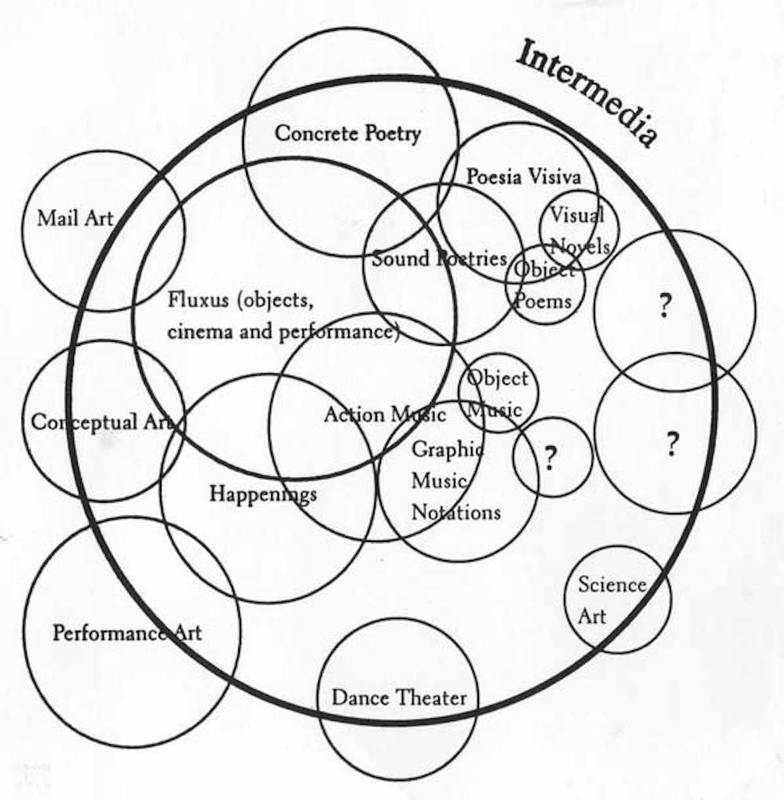

Fig. 12. Dick Higgins' Diagram of Intermedia as a Concept.

V. The Network and Modernism

What is modernism? How does it fit into the idea of a network, or the idea of a network into modernism?

Modernism is difficult to define, and in many ways, a strict definition of it contradicts some of its values. Nevertheless, some central ideas of and about modernism can be sketched, if provisionally. Marshall Berman’s All that is Solid Melts into Air (1982) is, in my opinion, a critical text about modernism, its provenance and its application as a literary and set of aesthetic movements, from which I’ve drawn many of these central ideas.

Modernism was primarily a response to modernity — a series of world-historical processes including but not limited to industrialization, new scientific knowledge and technology, urban growth, mass communication and capitalism (Berman 16). Modernism “nourished an amazing variety of visions and ideas that aim to make men and women the subjects as well as the objects of modernization” (Ibid.). These visions and ideas were a response to modernity. It is important to conceptualize modernism as a response to the change of world-historical processes; in part, what change meant for authenticity and originality (Benjamin 1936). Berman makes reference to “Baudelaire’s use of fluidity…and gaseousness…as symbols for the distinctive quality of modern life” (144) which reinforces the notion that modernism is defined in large part by change.

The changeability of modernism is a useful framework within which to examine Klee’s On modern art; a framework that necessitates a reminder of my three central theses. The medium, as defined by its form, is a type of change. So is the network, since nodes are different and therefore require that any movement between them involves change. Change can be defined synonymously as a process: it is a continuous action. If change is then a process that encompasses both media and network, it is possible to examine media and network in this project as a modernist form, which fits, since Klee was a modernist and On modern art is a modernist text. More specifically, having established that the networks of On modern art are defined by their own reproduction, the next step is to examine the ways in which these networks are intermedia characterized primarily by mimesis.

In an email exchange, Dr. Jentery Sayers defined intermedia as a “melding together of different media aspects that anticipates convergence” (email November 2). Sayers’ definition restates the poet Dick Higgins’ prominent conception of intermedia in foew&ombwhnw (1969), later presented by Higgins in A Dialectic of Centuries (1978), and reproduced in Figure 11. On modern art has a history (and a present) of different media aspects that suggest it can be read as a kind of intermedia. These media aspects include (but are, of course, not limited to) the lecture, the codex and the networks between lecture/text, artist and audience. Johanna Drucker suggests that the book (in her case, the art book) is a form of intermedia (6):

In some cases artists have made use of the documentary potential of the book form, while in others they have engaged with the more subtle and complicated fact of the book’s capacity to be a highly malleable, versatile form of expression. (Ibid.)

Klee’s On modern art, as a book, fits this understanding of intermedia. It has documentary potential, insofar as it “documents” Klee’s earlier lecture. But it is also a “malleable” and “versatile” form of expression since it existed earlier as an oratory lecture before being, in effect, translated into the form of a codex. This reproduction of Klee’s lecture I have earlier argued to be also a reproduction of a kind of network of communication surrounding Klee and his lecture. Moreover, I have argued that because of this reproductive value Klee’s text and network cannot be isolated as an im/material entity. This reproduction — and inability to be isolated — makes On modern art (as both a concept and a material) precisely a form of intermedia, or a “melding together of different media aspects that anticipates convergence.”

The idea and act of convergence, as well as the idea and act of change that I’ve focussed on as an aspect of modernism, connote process. I would like to consider the problematic of process — as change and convergence — through the heuristic device that is mimesis. Recall that mimesis is imitation, or more specifically “the representation or imitation of the real world in (a work of) art, literature, etc.” What makes mimesis salient in the context of On modern art is less that the codex is an imitation (in fact, a reproduction) and more that it is a representation of a moment or a unique time and place, that is the act of the lecture itself in 1924. I want to make reference to another Walter Benjamin text here: specifically “The Storyteller” (1936). Benjamin’s essay draws a contrast between the story — a mode of what Benjamin calls “experience” — and the novel — what he calls “information.” The distinction is elucidated on in this quotation:

The value of information does not survive the moment in which it was new. It lives only at that moment; it has to surrender to it completely and explain itself to it without losing any time. A story is different. It does not expend itself. It preserves and concentrates its strength and is capable of releasing it even after a long time. (90)

From this quotation, it is logical to define On modern art and the process that surrounds it as a kind of story or experience, since there is a preservation of concept, lecture as text and network that is released “after a long time” in the 1940s. Further analysis of this specific Benjamin text risks digression, but I would like to reiterate what makes “The Storyteller” relevant. That is, a story is, according to Benjamin, a kind of transference of experience: “the storyteller joins the ranks of the teachers and sages” (108). This transference of experience is a mimetic process, which is integral to my analysis of On modern art. It is a transference that represents a unique time and place but in a different form, which is, in a way, the central quality of the “experience” and the story while also being an act of mimesis. This discovery leads to several conclusions. The text is a kind of change; its changing form (from lecture to codex) is a representation. Quite literally, the text is re-presented in codex form, and this re-presentation required a process of mimesis, of the immaterial concept into the material “text”; of the experience of the lecture hall into the experience of reading. Thus On modern art as an object is encoded by change. And so is the four-part network in which it is embedded; the network changes alongside the transference from lecture to codex; with the audience that first heard Klee’s lecture and now reads this book; and as a story of the codex. What the representation of On modern art and the network surrounding it means, in this project, is then curiously a kind of meta-commentary on Klee’s own work and on modernism itself. On modern art seems almost to take on the form of modernism as it is defined by change. Given that Klee died before the publication of this codex — that he, in other words, had no influence or control over it — the conclusion that On modern art is inadvertently a meta-argument about modernism and a commentary on itself is either serendipitous or a precise and compelling proof for Marshall McLuhan’s claim that the medium is the message.

In spite of this serendipity and/or proof and the conclusions it facilitates about On modern art, there remains an as-of-yet unanswered question about the study of the book as an object. How do we evaluate the codex as an object if the story of this codex is fundamentally one of change or fungibility? We know that one argument with staying power in media studies is that the medium is the message, and therefore the changes to and surrounding On modern art are its message. At the same time, the Special Collections copy of this codex that I have worked with is not an item that “is change” to put it awkwardly. The codex is not change enacted or a kind of middle, a pure idea or representation. It is a material object. Regardless of the fact that there are multiple copies of this publication, this specific copy — in Special Collections at the University of Victoria — is unique. It is only, as an object, itself: it has only its own time(line) and only its own place. This copy of On modern art cannot be in more than one place at more than one time. And yet, this project has sought to investigate On modern art as a medium and has argued that it is defined at least in part by its existence as a process of reproduction, which is a kind of being in more than one place and more than one time. The question must, therefore, be asked about how to ascertain the authenticity of On modern art. Is its authenticity its existence as a medium, or its existence as a book? I have chosen to turn to Benjamin once again in an attempt to answer this question:

The authenticity of a thing is the quintessence of all that is transmittable in it from its origin on, ranging from its physical duration to the historical testimony relating to it. (Benjamin 22)

By this argument, On modern art’s existence both as a medium and as a book are its authenticity. At the same time, Benjamin in this essay argues that reproduction profoundly modifies the effect of a work of art (21), an argument that I have extended to the network outlined in the introduction. It would follow that the network’s reproduction — its modifying effect — is its authenticity, an argument that Benjamin does in fact make. But if “modifying effect” is, literally, change, then how do evaluate this specific codex as an object that is unique since it itself has its own time and place, an understanding that seems to locate the object’s authenticity in its eternally immediate static existence, an existence that is simultaneously modified at every moment by the passage of time? The answer to that question begets another project.

✧✧✧

VI. Further Reading

Are you interested in the relationship between philosophy and modernist art? If you have institutional library access, see Stephen H. Watson's Crescent Moon over the Rational: Philosophical Interpretations of Paul Klee, for a discussion of Klee's impact on 20th-century Western thinkers. [link requires UVic library login privileges]

Are you interested in seeing more of Klee's artwork, or which galleries to visit? Take a look at the collections from the Tate, the Guggenheim, the Museum of Modern Art, or Zentrum Paul Klee.

Are you interested in learning more about Modernist publishers? Visit the Modernist Archives Publishing Project for a critical digital archive of early 20th-century publishers.

Are you interested in Digital Humanities and the process of archival projects? Scholarly Adventures in Digital Humanities: Making The Modernist Archives Publishing Project (New Directions in Book History) provides a detailed discussion of the Making of the Modernist Archives Publishing Project. [link to Amazon.ca]

Are you interested in learning more about the relationship between modernism and art? Visit this section of the Tate's website.

Are you interested in American modernist art? Take a look at this review in The Guardian of an exhibit of modernist American paintings at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

Are you interested in learning more about modernism, and the various lenses that have been used to assess and investigate it? Palgrave MacMillan's Modernism and... series covers modernism's relationship to, amongst other things, phenomenology, Christianity, totalitarianism, and style...

Are you interested in learning more about postmodernism? Take a look at this description of postmodernism from the Tate or the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy's entry on postmodernism.

VII. Works Cited

Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility.” The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media, edited by Jennings, Michael W., Doherty, Brigid and Thomas Y. Levin, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2008, pp. 19-55.

Benjamin, Walter. “The Storyteller.” Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, edited by Hannah Arendt, Schocken Books, 2007, pp. 83-110.

Berman, Marshall. All That is Solid Melts into Air. Penguin Books, 1982.

Brown, Bill. “Materiality.” Critical Terms for Media Studies, edited by Mitchell, W.J.T. and Mark Hansen, The University of Chicago Press, 2010, pp. 49-63.

“concept, n.” OED Online. Oxford University Press, 2018. http://www.oed.com.ezproxy.library.uvic.ca/view/Entry/38130?rskey=tXcfz6&result=1&isAdvanced=false#eid

Dean, Heather. “Re: ENGL500 text history.” Received by SH. 6 November 2018.

Drucker, Joanna. The Century of Artists’ Books. Granary Books, 1995.

Drucker, Joanna. “Art.” Critical Terms for Media Studies, edited by Mitchell, W.J.T. and Mark Hansen, The University of Chicago Press, 2010, pp. 3-18.

"Faber and Faber Limited." British Literary Publishing Houses, 1881-1965. Ed. Jonathan Rose and Patricia Anderson. Vol. 112. Detroit, MI: Gale, 1991. 114-118. Dictionary of Literary Biography Vol. 112. Dictionary of Literary Biography Complete Online. Web. 24 Oct. 2018.

Galloway, Alexander. “Networks.” Critical Terms for Media Studies, edited by Mitchell, W.J.T. and Mark Hansen, The University of Chicago Press, 2010, pp. 280-296.

Gitelman, Lisa. Paper Knowledge: Toward a Media History of Documents. Duke University Press, 2014.

Higgins, Dick. foew&ombwhnw. Something Else Press, 1969.

Higgins, Dick. A Dialectic of Centuries: Notes Towards a Theory of the New Arts. Printed Editions, 1978.

Klee, Paul. On modern art. Faber and Faber, 1948.

McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media. McGraw-Hill, 1964.

“mimesis, n.” OED Online. Oxford University Press, 2018. http://www.oed.com.ezproxy.library.uvic.ca/view/Entry/118640?redirectedFrom=mimesis#eid

Mitchell, W.J.T. Picture Theory. University of Chicago Press, 1994.

Mitchell, W.J.T. "What do Pictures "Really" Want?" October, vol. 77, 1996, pp. 71-82.

“process, n.” OED Online. Oxford University Press, 2018. http://www.oed.com.ezproxy.library.uvic.ca/view/Entry/151794?rskey=HhToOE&result=1&isAdvanced=false#eid

“reproduction, n.” OED Online. Oxford University Press, 2018. http://www.oed.com.ezproxy.library.uvic.ca/view/Entry/163102?redirectedFrom=reproduction#eid

Sallis, John, editor. Paul Klee: Philosophical Vision: From Nature to Art. McMullen Museum of Art, 2012.

Sayers, Jentery. “Re: Update on PTP.” Received by SH. 2 November 2018.

✧✧✧

VIII. Additional Scholarly Citations

Harrison, Charles and Paul Wood, editors. Art in Theory: 1900-2000. Blackwell Publishing, 2003.

Innis, Harold. Empire and Communications. Rowman & Littlefield, 2007.

Kittler, Friedrich. Gramophone, Film, Typewriter. Stanford University Press, 1999.

Mitchell, W.J.T. and Mark Hansen, editors. Critical Terms for Media Studies. University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Peters, John Durham. The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media. University of Chicago Press, 2015.