Collection of Plays Performed at the Theatres Royal in London and Dublin (1764-1801)

Introduction

Among the treasures in the University of Victoria library’s Special Collections are two unassuming volumes of plays from the mid-to-late eighteenth and very early nineteenth century. When perusing their pages, it is striking to discover the apparent randomness of the collection: other than the single word Plays faintly printed on their spines, the volumes have no collective title. The title pages for each play have varying publication statements and a broad range of years printed (between 1764 and 1801). The library even made the choice to catalogue each play separately under the same call number, for example, here.

Evidently, the play pamphlets themselves were printed and issued separately. In addition to the clues listed above, the differing typefaces and paper textures make this apparent. We can reasonably conclude, then, that the scripts were subsequently gathered and bound into these volumes, making this collection truly one-of-a-kind. The plays contained in this collection in the order they appear are as follows:

Volume One

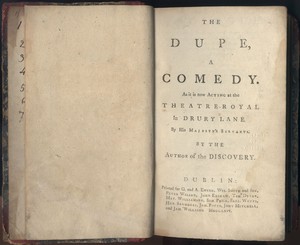

The Dupe, a Comedy by Frances Chamberlain Sheridan, printed in 1764 (the earliest of the collection)

The Miser, a Comedy by Henry Fielding, printed in 1788

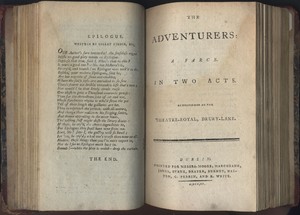

The Adventurers: A Farce in Two Acts by Edward Morris, printed in 1799

Love in the East: or, Adventures of Twelve Hours: A Comic Opera in Three Acts by James Cobb, printed in 1788

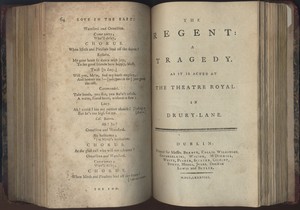

The Regent: a Tragedy by Bertie Greatheed, printed in 1788

Romeo and Juliet. A Tragedy by Shakespeare. With Alterations and an Additional Scene by D. Garrick, Esq., printed in 1768

The Maid of the Oaks: A New Dramatic Entertainment by General John Burgoyne, printed in 1775

Volume Two

Harvest-Home: A Comic Opera in Two Acts by Charles Dibdin, printed in 1788

The Duenna: A Comic Opera in Three Acts by Richard Brinsley Sheridan, printed in 1776

Paul and Virginia: A Musical Drama in Two Acts by James Cobb, printed in 1801

The Castle Spectre: A Drama in Five Acts by Matthew Lewis (author of The Monk), printed in 1799

The Battle of Hastings: A Tragedy by Richard Cumberland, printed in 1778

Peeping Tom of Coventry: A Comic Opera by John O’Keefe, printed in 1785

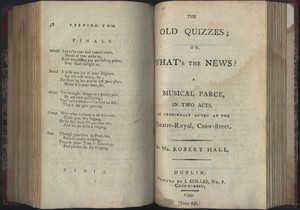

The Old Quizzes; or, What’s the News? A Musical Farce in Two Acts by Robert Hall, printed in 1799

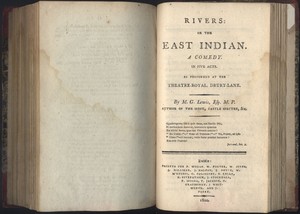

Rivers: or The East Indian. A Comedy in Five Acts by Matthew Lewis, printed in 1800

Even considering this seemingly random assortment of plays, several unifying patterns emerge. All of the plays were at one time performed at one or more of the Theatres Royal in London and/or Dublin, as is referenced on the majority of the individual title pages. Even the two that make no mention of this on their title pages (Lewis’s The Castle-Spectre and Sheridan’s The Duenna) were, in fact, performed at the Theatre Royal. The Castle-Spectre’s first performance took place at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane in December, 1797 (Leask), and The Duenna enjoyed a season at the same theatre in 1775 (Dobbs 108). Also, as shown in the gallery of title pages below, every one of the plays was published in Dublin, Ireland.

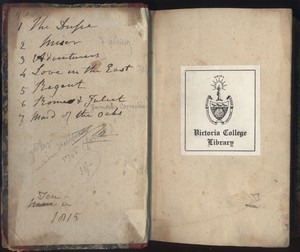

Inside front cover of Volume One showing a table of contents handwritten by a previous owner, initialed "GM," other marginalia, and a Victoria College Library bookplate.

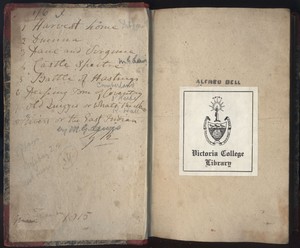

Inside front cover of Volume Two also showing a table of contents handwritten by previous owner "GM," other marginalia, a Victoria College Library bookplate, and the Alfred Bell ownership mark, curiously missing from Volume One.

Special Collections sent these well-loved books to the Meadland Bindery in Brentwood Bay for intensive repair in 2004, detailed in this Conservation Treatment note pasted on the inside back covers of each volume.

Traces of Past Readers

The first two images to the left display the inside front covers of each volume of Plays. According to Heather Dean, Associate Director of Special Collections, the Victoria College Library bookplates indicate that this collection came from the precursor institution to the University of Victoria; the donor information is no longer known, but it has been in Special Collections' possession for many decades.

In her handbook, Books Will Speak Plain, Julia Miller defines marginalia as "notes and comments written in the margins of text pages or on endpapers that may or may not refer to the text" (Miller 292). A charming feature of this collection of plays is the makeshift tables of contents handwritten into each volume by a former reader, only identified by his or her signed initials, "GM." We can see, too, that another reader later scribbled in the names of several of the playwrights in pencil, and that penmanship matches that of the note reading "7 plays including Shakespeare 1768 (Garrick)." Volume Two also features the owner mark (Miller 291) of an Alfred Bell.

"Margin notes," Miller writes, "were abhorred for a long time as disfiguring unless they were inscribed by the famous. Today, we have a greater appreciation for what such comments can tell us about...readership in earlier eras" (Miller 292). The identities of these readers will likely remain unknown; however, the marginalia, stained paged throughout, and evidence of damage and repair reveal that this collection was well-loved by its readers over the centuries.

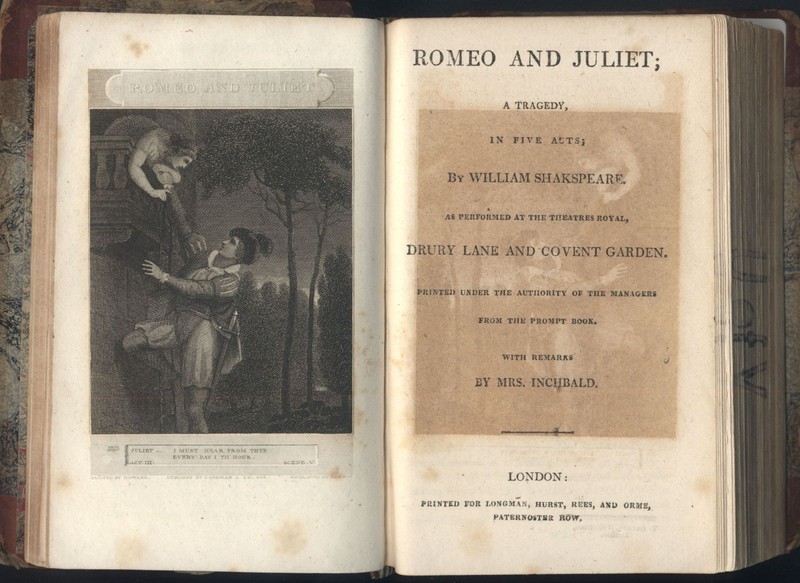

The title page of David Garrick's revision of William Shakespeare's famous tragedy Romeo and Juliet.

This gallery features the title pages of each play contained in this two-volume collection. Notice the variety of playwrights and genres, and the expanse of years over which the individual leaflets were printed (1764 - 1801).

In spite of this puzzling miscellany, some uniting aspects emerge: the majority of these title pages make reference to the plays being performed at the Theatre Royal (many at Drury Lane, which David Garrick co-managed for nearly three decades), and each pamphlet was printed in Dublin.

Julia Miller explains that "the eventual inclusion of the phrase 'printed by...for...' could mean for the author, for the publisher, for the bookseller, or a combination, since publishing and bookselling were at times also combined in the same person, who still might be the printer and binder as well. It takes a great deal of knowledge and experience to unscramble the information on some title pages" (Miller 159). Note the name C. Jenkin listed among those for whom The Maid of the Oaks was printed, and read more about him below.

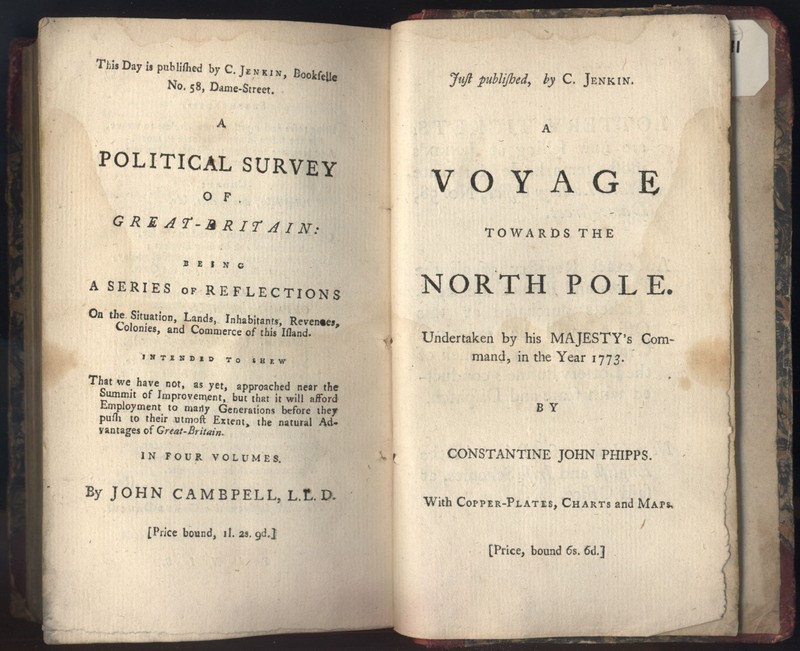

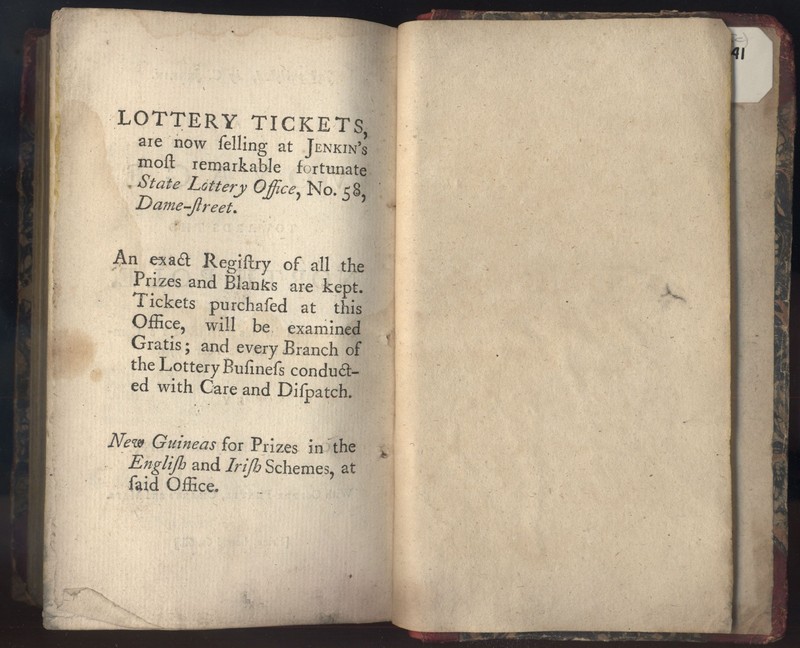

Advertisements for additional books published and sold by C. Jenkin, bound at the end of Volume One of Plays.

Julia Miller explains that “[s]ome of the advertisements include not only information about books in stock or books to be published, but…also all the other wares a bookseller and stationer might carry” (Miller 168). In addition to bookselling, C. Jenkin also operated a state lottery office at 58 Dame Street. This advertisement for lottery tickets is bound at the very end of Volume One of Plays.

This segment of a facsimile of John Rocque's 1756 map of Dublin shows the approximate location of 58 Dame Street in Temple Bar, the eventual location of C. Jenkin's bookshop and lottery office.

No. 58 Dame Street as it appears today on Google Maps. A pizza restaurant and hostel now operate at this address.

C. Jenkin, Bookseller, and So Much More

"CALEB JENKIN begs Leave to return his sincere Thanks to his Friends and the Public, for their kind Protection, which he has so amply experienced for the last ten Lotteries, and assures them he will sell Tickets, Shares, &c. on the lowest Terms.

He thinks it necessary to inform his Friends and Customers, that he is not concerned in any other Office, and shall thank them for a Continuance of their Favours, at his old established Office, No. 58, Dame-street, Dublin"

-Advertisement in Saunders’s News-Letter, April 11, 1781

The images to the right show three advertisements bound into the back of one volume of Plays. Julia Miller explains that "[i]t has been the unfortunate practice of some collections to have such advertisements cut out of volumes when they are rebound in order to save shelf space, a practice that destroys valuable research information and the integrity of the original work” (Miller 288-289). Luckily, Volume One of Plays retains its final three pages: these advertisements reveal the name and address of the likely original Dublin bookseller: C. Jenkin, No. 58. Dame-Street.

I am indebted to the work of Mary Pollard, whose exhaustive book, A Dictionary of Members of the Dublin Book Trade 1550-1800, synthesizes evidence from numerous primary sources and records, and from which I learned much about Caleb Jenkin’s life and the nature of the Dublin book trade of this period.

After apprenticing for bookseller and binder Samuel Watson, Caleb Jenkin opened his bookshop on August 10th, 1771, and operated it until his death (Pollard, “Jenkin” 318). No. 58 Dame Street was (and is still) located in the lively and central Temple Bar neighbourhood, a mere two blocks from City Hall.

"Married.] A few days ago at Waterford, Mr. Caleb Jenkin, bookseller, of this city, to Miss Anne Norrington."

-Announcement in Saunders's News-Letter, June 28, 1773

He was a member of the Guild of St. Luke the Evangelist, a “corporation of cutlers, painters, paper-stainers, and stationers” (Kennedy 130). Jenkin belonged to the last group, as the “[s]tationer to the Post-office and Police” (Pollard, “Jenkin” 318). Tragedy struck on February 6th, 1782 when, at a Guild meeting at the Music Hall on Fishamble Street “to nominate a candidate to represent the city of Dublin in Parliament” (Kennedy 130), a rotten beam collapsed, crushing dozens of those assembled. Eleven people ultimately died (Kennedy 131), and Caleb Jenkin was listed by the local newspapers as being among the injured (“Much bruised” [Kennedy 134]), all of whom “were well-known businessmen in the city, whose condition was of public interest” (Kennedy 132).

Pollard explains that “the ordinary bookseller-printer, depended, of course, on other merchandise besides books…The Dublin Directory shows that a number of other trades were apparently compatible with bookselling, including those of letter-founder, haberdasher, perfumer, stockbroker, hatter, pawnbroker, and feather-merchant” (Pollard, Dublin’s Trade 193). In his book Printing and Bookselling in Dublin 1670 – 1800, James W. Phillips hypothesizes that “perhaps such a variety of stock was necessary to insure a livelihood or perhaps the Dublin bookseller was, above all else, a businessman” (Phillips 91). As we see, Caleb Jenkin used the books he sold to advertise his side business: selling lottery tickets. The lottery was, according to Phillips, “the truly rival activity indulged by the booksellers…and beginning with the year 1770 a bookseller’s advertisement as often concerned the lottery tickets he had for sale as for the books he had recently published” (Phillips 92).

Jenkin, along with an Ambrose Leet (Warburton xlvi), was elected High Sheriff of Dublin in October of 1784, and then served as an Alderman in November 1790 (Pollard, “Jenkin” 318-319). “Aldermanic status,” Pollard clarifies, “can be equated with a certain degree of prosperity, because by 1778 the City required that its High Sheriffs should be elected only from those worth more than £2,000 ‘in estate and possession’” (Pollard, Dublin’s Trade 193). Knowing this, we can conclude that Jenkin likely profited amply from his lottery business.

Caleb Jenkin died on March 16th, 1792 and was buried at St. Andrew’s (Pollard, “Jenkin” 319). These details of his life, scattered as they may seem, begin to form the mosaic of C. Jenkin’s character: as a citizen and businessman active and respected in his community. As a bookseller, he functioned as the key link between the public and print material.

One research problem remains unsolved: If Jenkin was indeed the original bookseller of this collection, how do we account for the plays included that were printed years after his death? Perhaps the volumes were rebound later with the new additions and Jenkin's advertisements left intact, or perhaps his shop continued to operate for some time after his death. Future research may resolve this puzzle.

Thomas Gainsborough's 1769 portrait of David Garrick, appropriately learning on a bust of Shakespeare. (Wikimedia Commons)

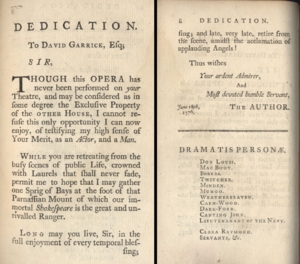

The first two pages of Romeo and Juliet listing the Dramatis Personæ and the beginning of the first scene. David Garrick and Susannah Cibber starred in the title roles in this production.

Note the apt reference to Shakespeare in Richard Brinsley Sheridan's dedication of his comic opera, The Duenna, to David Garrick. According to Brian Dobbs, in his book Drury Lane: Three Centuries of the Theatre Royal 1663-1971, Sheridan got his wish for The Duenna to be performed on Garrick's stage, and enjoyed a booming run at Drury Lane Theatre in 1775 (Dobbs 108). Curiously, however, this dedication is dated June 18th, 1776, which appears to contradict Dobbs and could be the subject of future research. Upon Garrick's retirement in 1776, Sheridan purchased his share in Drury Lane Theatre and succeeded Garrick as manager (Dobbs 109).

The tomb scene from Garrick's revision of Romeo and Juliet. Here, his version diverge's from Shakespeare's significantly: Juliet awakes before Romeo dies, allowing the star-crossed lovers a final, more satisfying and audience-pleasing farewell scene.

Benjamin Wilson's 1753 painting of George Anne Bellamy as Juliet awaking in the Capulets' tomb before David Garrick's Romeo dies. (Wikimedia Commons)

David Garrick and the God of his Bardolatry

Though intended to be humorous, the following stanza, from a poem written and recited by David Garrick to commemorate the opening of the 1750 season at Drury Lane Theatre ("An Account" 247), captures Garrick’s awareness of the need to straddle his adoration of William Shakespeare and the tastes of the public:

Sacred to SHAKESPEARE was this spot design'd,

To pierce the heart and humanize the mind.

But if an empty House, the Actor's curse,

Shews us our Lears and Hamlets lose their force;

Unwilling we must change the nobler scene,

And in our turn present you Harlequin...

If want comes on, importance must retreat;

Our first great ruling passion is - to eat. ("An Account" 247)

A formidable talent, David Garrick was recognized as “the premier actor of his day” (Wright 68) but, beyond that, he was also a playwright, theatre manager, producer, and “occasional poet” (Dircks 1). Phyllis T. Dircks notes that “[a]t the height of his career he was undeniably the most famous and most important theatrical personality of his age, known and applauded by his countrymen; acknowledged, sometimes grudgingly, by his antagonists, and exalted by continental Europeans” (Dircks 4). His impact endures to this day as he is widely lauded as being arguably the most influential figure in shaping our cultural appreciation – infatuation, even – with Shakespeare.

The majority of the plays contained in this collection (notably every play in Volume One) were at one time performed at Drury Lane Theatre, which Garrick co-managed with James Lacy from 1747 (Pedicord xxiv) until his retirement in 1776 (Pedicord xxv). Over these decades, he produced a total of “twenty-six Shakespeare plays, in fourteen of which he took seventeen roles” (Pedicord xiv), and many of the performance scripts were his own revisions of Shakespeare’s work. One such revision is included in this collection: Garrick’s version of Romeo and Juliet.

Regardless of whatever discomfort one may feel regarding the notion of editing Shakespeare, to Garrick belongs credit for successfully reintroducing Romeo and Juliet to the London stage in 1748, “during the first year of his managerial tenure” at Drury Lane (Dircks 83). Since 1679, it had been superseded entirely by Thomas Otway’s The Rise and Fall of Caius Marius, “which interpolated great chunks of Romeo and Juliet into a new plot” (Branam 170). George C. Branam explains that “[n]ot, of course, by current standards, but by those of his day, [Garrick] was faithful to Shakespeare's text, making only those changes he thought necessary for audience acceptance” (Branam 175). The significant changes made to Shakespeare’s text are detailed below.

The sudden change of Romeo’s love from Rosaline to Juliet, was thought by many, at the first revival of the play, to be a blemish in his character; an alteration in that particular has been made more in compliance to that opinion, than from a conviction that Shakespeare, the best judge of human nature, was faulty.

-From Garrick's explanation to the reader of changes made to Shakespeare's script (Garrick qtd. in Pedicord 79)

In his messages to the readers included in printed editions of the script (though not included in the version in this copy from Special Collections), David Garrick explained that “the Design was to clear the Original, as much as possible, from the Jingle and Quibble, which were always thought the great Objections to reviving it” (Garrick qtd. in Pedicord 77). By “jingle and quibble,” Garrick refers to Shakespeare’s puns, wordplay, sexual references, and the rhymed verse which he changed to “sound more like dialogue” (Wright 63). He also “omitted all references to Romeo’s first love, Rosaline, in order to idealize the young star-crossed lovers” (Pedicord xv), which, as the quotation above implies, was more a “matter of bowing to public taste” than an alteration made enthusiastically (Wright 59). Garrick’s script added an “elaborate funeral procession staged for [Juliet]…when she is under the influence of the potion…an opportunity for spectacle that Garrick could not pass up” (Wright 60-61), and the most notable departure of all: Juliet wakes in the tomb before Romeo’s poison takes effect. This opportunity for a final farewell that takes place between the star-crossed lovers involved adding seventy-five original lines of dialogue to the tomb scene (Pedicord xv), giving Romeo, Juliet, “and the audience the satisfaction of…dignity, purity, sentimental sadness and understanding as they die” (Wright 62-63).

David Garrick’s revision and production of Romeo and Juliet was so successful that it “achieved the status of virtual authenticity” (Copeland 1) and dominated the London stage for nearly a century, many decades after Garrick’s death (Wright 52). Although many would deem it blasphemous to alter the work of William Shakespeare, the considerable irony in finding fault with Garrick’s practice is that he is the one responsible for creating the quasi-religious cultural fervor surrounding the Bard in the first place, “putting the poet on England’s cultural calendar in a way that no other English author had so far enjoyed or ever would” (Kahn and Calvo 6). Garrick’s persistence made Shakespeare-worship a practice involving “temples and monuments, idolatry and jubilation” (Holland 15), which endures today as Bardolatry. George C. Branam contextualizes the issue in this way:

[Garrick’s] readiness, even alacrity, in making concessions to the taste of his audience has raised doubts as to the depth of his own taste and the sincerity of his professed devotion to Shakespeare. The successive stages of his Romeo and Juliet clarify the problem, and if they do not show him to be a purist, he is at least perceptive and appreciative of Shakespeare's merits…His professed love of Shakespeare was genuine: it was the love of a man of the theatre, derived more from Shakespeare's mastery of the stage than from his profundity as a poet, though not insensitive to that either. Garrick was a great actor and an extraordinary manager…He wanted to propagate Shakespeare in his theatre – and to fill that theatre with paying, applauding customers. He achieved both to a remarkable degree. (Branam 179)

Fewer than three years into his retirement, David Garrick died on January 20th, 1779, and is buried in Poets' Corner in Westminster Abbey (Pedicord xvi) where the following words are inscribed on his marble monument (Stone 183):

To paint fair nature by divine command,

Her magic pencil in his glowing hand,

A Shakespeare rose: then to expand his fame

Wide o'er this breathing world, a Garrick came.

Tho' sunk in death the forms the poet drew,

The actor's genius bade them breathe anew;

Though like the bard himself, in night they lay

Immortal Garrick call'd them back to day;

And till Eternity with power sublime

Shall mark the mortal hour of hoary Time

Shakespeare and Garrick like twin stars shall shine

And earth irradiate with a beam divine.

This Romeo and Juliet, also Garrick's revision, appears in another collection of Theatre Royal plays housed in Special Collections. This collection is from 1808 and has 25 volumes.

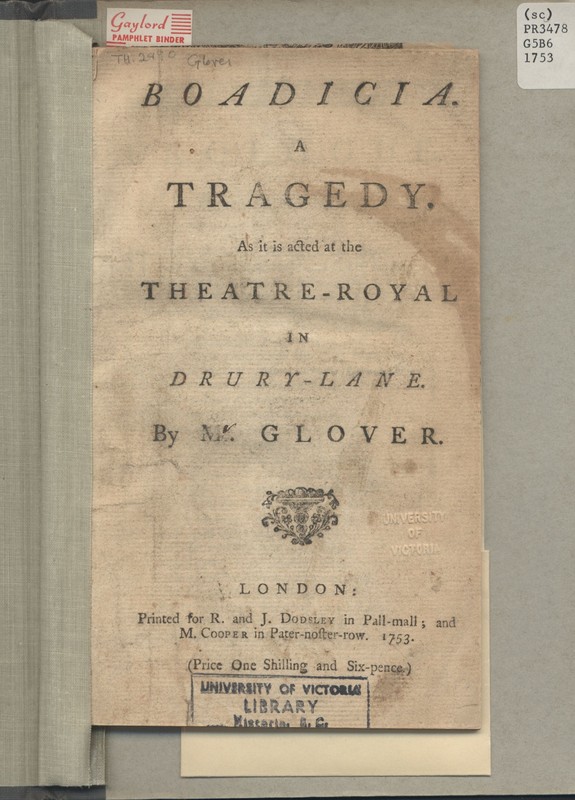

Special Collections has an impressive selection of plays from this era, many of them in their original pamplet format, like this tragedy by Richard Glover.

See Also

Also in Special Collections:

A collection of plays performed at the Theatres-Royal - 125 in 25 volumes

Other plays performed at Drury Lane Theatre under David Garrick's management:

Every Man in his Humour: A Comedy, 1752

Boadicia: A Tragedy, 1753

All in the Wrong: A Comedy, 1761

The Way to Keep Him: A Comedy in Five Acts, 1761

The School for Lovers: A Comedy, 1762

The Revenge: A Tragedy, 1764

The Clandestine Marriage: A Comedy, 1766

The Register-Office: A Farce of Two Acts, 1771

The Fashionable Lover: A Comedy, 1772

Isabella, or, The Fatal Marriage, 1773

Also on Movable Type:

On readership traces:

Regia de la Sagrada Orden De Penitencia by Antonio de Tablada, c. 1528-1530

Bianthanatos by John Donne, 1648

Existentialism and Human Emotions by Jean-Paul Sartre, 1947 / 1957

The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath, 1963

On advertisements:

Bianthanatos by John Donne, 1648

Poems of Ossian by James Macpherson, 1762

Bentley's Miscellany, 1838

Household Words conducted by Charles Dickens, 1850-1859

Woman's World edited by Oscar Wilde, 1887-1890

The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde, 1890-2011

The Strand Magazine, 1891-1950

BLAST: Review of the Great English Vortex, 1914-1915

Castle of Frankenstein, 1962-1975

On theatrical texts:

The History of the World by Sir Walter Ralegh, 1614

The Play of Pericles, Prince of Tyre by William Shakespeare (Barbarian Press), 2010

GK/Fall2017

Works Cited

“An Account of the Late David Garrick, Esq.” The European Magazine and London Review, Containing Portraits, Views, Biography, Anecdotes, Literature, History, Politics, Arts, Manners, and Amusements of the Age, Oct. 1809, pp. 243–248.

Branam, George C. “The Genesis of David Garrick's Romeo and Juliet.” Shakespeare Quarterly, vol. 35, no. 2, 1984, pp. 170–179.

Copeland, Nancy. “The Sentimentality of Garrick's Romeo and Juliet.” Restoration and Eighteenth Century Theatre Research, vol. 4, no. 2, 1989, pp. 1–13.

Dircks, Phyllis T. David Garrick. Twayne Publishers, 1985.

Dobbs, Brian. Drury Lane: Three Centuries of the Theatre Royal 1663-1971. Cassell & Company, 1972.

Holland, Peter. “David Garrick: Saints, Temples and Jubilees.” Celebrating Shakespeare: Commemoration and Cultural Memory, edited by Coppelia Kahn and Clara Calvo, Cambridge University Press, 2015, pp. 15–37.

Jenkin, Caleb. “Lottery Tickets Insured to Any Amount.” Saunders's News-Letter, 19 Mar. 1781.

Kahn, Coppelia, and Clara Calvo. “Introduction: Shakespeare and Commemoration.” Celebrating Shakespeare: Commemoration and Cultural Memory, Cambridge University Press, 2015, pp. 1–14.

Kennedy, Máire. “Disaster at the Music Hall, Fishamble Street, 6 February 1782.” Dublin Historical Record, vol. 50, no. 2, 1997, pp. 130–136.

Leask, Nigel. “Lewis, Matthew Gregory.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 17 Sept. 2015.

“Married.” Saunders's News-Letter, 28 June 1773.

Miller, Julia. Books Will Speak Plain: a Handbook for Identifying and Describing Historical Bindings. Legacy Press, 2010.

Pedicord, Harry William, and Frederick Louis Bergman, editors. The Plays of David Garrick: Garrick's Adaptations of Shakespeare 1744-1756. Vol. 3, Southern Illinois University Press, 1981.

Phillips, James W. Printing and Bookselling in Dublin, 1670-1800 : a Bibliographical Enquiry. Irish Academic Press, 1998.

Pollard, Mary. Dublin's Trade in Books 1550-1800. Clarendon Press, 1989.

Pollard, Mary. “Jenkin, Caleb.” A Dictionary of Members of the Dublin Book Trade 1550-1800 Based on the Records of the Guild of St. Luke the Evangelist Dublin, London Bibliographical Society, 2000, pp. 318–319.

Rocque, John, et al. “Exact Survey of the City and Suburbs of Dublin.” Historic Dublin Maps, National Library of Ireland, 1988, p. 8.

Stone, George Winchester. “David Garrick's Significance in the History of Shakespearean Criticism: A Study of the Impact of the Actor upon the Change of Critical Focus during the Eighteenth Century.” PMLA, vol. 65, no. 2, 1950, pp. 183–197.

Warburton, John, et al. History of the City of Dublin, from the Earliest Accounts to the Present Time. Vol. 2, W. Bulmer and Co. Cleveland-Row, St. James, 1818.

Wright, Katherine L. Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet in Performance: Traditions and Departures. Edwin Mellen Press, 1997.