Andrew W. Tuer (ed.), Pages and Pictures from Forgotten Children's Books (1899)

“The love of things rendered quaint and interesting by lapse of time and change of surroundings seems to grow on one imperceptibly. We have all wondered whether the elders who presented, and the children who read these forgotten little books, recognised the unconscious humour of the writers of the text and the drawers of the pictures.” (1)

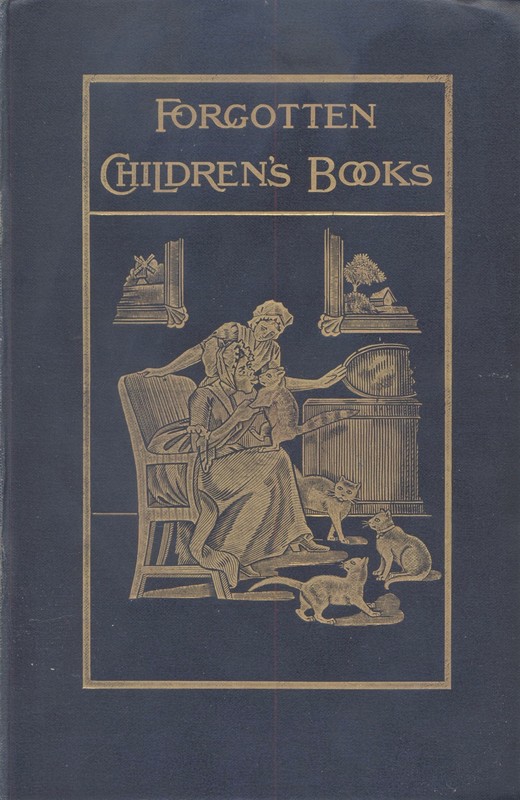

So begins Andrew White Tuer in his introduction to Pages and Pictures from Forgotten Children's Books, a collection of 103 children's texts and illustrations. Published in 1899, Forgotten Children's Books was assembled, edited, printed, and published by Tuer's Leadenhall Press, which he founded, owned, and operated. Children’s literature was one of Tuer's many passions, and many of the books he featured in Forgotten Children’s Books were from his own collection (8). His Leadenhall Press would reprint several works of children’s literature from the early nineteenth century, including some selections from Forgotten Children’s Books. Tuer would later publish a companion volume entitled Stories from Old-Fashioned Children’s Books, which was focused more upon reprinting whole texts rather than primarily illustrations.

Forgotten Children’s Books (heretofore referenced as FCB) can be read as a Victorian miscellany, a collection of works from different authors and illustrators, condensed and sold as one publication. While such a collection is more commonly described now as an anthology, it is important to distinguish, as Michael Suarez describes, how anthologies tend to historicise and canonise works, while miscellanies are usually constructed around a certain time period and theme while avoiding historical judgment (218-19). Tuer speaks to this inclusivity in his introduction, where he says:

“The material is so great that in a single volume—which has no object but to amuse—the fringe only can be touched. In these “tastes” the reader will miss the names of authors and artists of conspicuous repute, and it will be observed that others of no repute whatever are conspicuous by their presence.” (8)

This equitable, inclusive approach to the book indicates that Tuer is attempting to create what I will call a nostalgic network with his readership. “Perhaps it would be well not to try to swallow these little stories at a gulp,” Tuer says in his introduction to Stories from Old-Fashioned Children’s Books, the companion miscellany volume to FCB. “Better mark twain, read them and put the book away for a time” (xv-xvi). These books are not intended to be read start-to-finish, nor are they to be read as comprehensive histories of late-seventeenth century children’s literature, nor are any of the featured books intended to be celebrated above any other; his book is designed to evoke nostalgic responses in those who flip through it. Indeed, Helen Groth’s description of Victorian nostalgia reflects this objective: “Rather than claiming authority, nostalgia works variously and dynamically to uncover, evoke, and familiarise the past” (6). If we return to this introduction, we can see these strategies at work when Tuer suggests how nostalgia can grow “imperceptibly.” Later, he rhetorically asks what a “modern child” will think when presented with this material (5-6), which suggests this volume is not necessarily intended for modern children, but rather those who were familiar with—and long for— the original works.

While an investigation of nostalgia as a literary concept is outside the scope of this Omeka exhibit, I would like to use this space to think about the other networks Forgotten Children’s Books unintentionally obscures. To create a children’s book is to create a network between author, illustrator, editor, printer, publisher, seller, and reader. The stories of those relationships are often as interesting as the finished product; Tuer was aware of this, and gives us a taste of some historical and bibliographical information in his introduction:

“A capital little book, notable as being a favourite with our Queen-Empress when a child, is ‘Ellen, or the Naughty Girl Reclaimed,” which formed one of a series of a dozen or more under different titles. The prettily tinted cut-out illustrations were on cardboard, separate from the text. A movable head, which, through much handling soon shewed signed of wear, fitted into a groove behind the neck, and completed one of the pictures at a time. These little book-toys, which ran into many editions and were copied by German and French publishers, were prime favourites with two or three generations of children, and are now difficult to find.” (9)

Tuer had the ability to provide the reader with historical and bibliographical information, yet this was not his objective; his objective was only to “amuse,” to evoke a nostalgic response. This affectation can be found not only in the selected children’s works, but also in the material book itself. Andrew Tuer was known not only for his antiquarian hobbies in terms of his press’ content, but also in the form in which they were printed. Tuer was both celebrated and decried for his antiquarian approach. In 1893, The British Printer praised the Leadenhall Press’ unique and innovative approach, while Tuer was described by Colin Clair in his History of Printing in Britain as a publisher who let his admiration of late-eighteenth century English printing mar his work (257). Regardless of the critical opinion of Tuer’s printing work, the Leadenhall Press was notable for the appearance of their printed works, and, as B.J. McMullin notes, for Tuer’s predilection towards “the possibilities of current materials and technologies” (161).

But the nostalgic networks are not the only networks within the book. Fitting with the genre of Victorian miscellany, Tuer is dedicated to evoking nostalgia in his readers while avoiding disclosing background information to his selections, as we find in his introduction:

“The insertion of notes made by the writer would have much curtailed these pages and pictures, with which, as it is, occasional liberties in the way of space-saving backing of title page, etc., have been taken. . . . The serious or antiquarian side of the subject—the evolution of nursery stories, with notes on the histories and achievements of the writers of forgotten books for children, the designers, engravers, and their thrice-removed cousins—must wait.” (9-10)

Unfortunately, Andrew Tuer would pass away a year after the publishing of this book from a sudden illness (Young 33). The historical, bibliographical element of these books—the networks between the various actors who produced them—remain obscured. However, in this Omeka exhibit, I seek to remediate the collected children's texts and illustrations of this book, and the networks they represent, in a manner akin to Tuer. Just as he utilized “the possibility of current materials and technologies” (McMullin 161), I will use digital mediums to illustrate the less visible networks in this book, in an attempt to answer the following questions:

- How can one define, interpret, and illustrate the networks found within this book, between its editor and the various authors, illustrators, publishers, sellers, and readers?

- By condensing the excerpts from these children's books into one or two pages/illustrations, will they remain "forgotten?" How will the excerpted texts compare to full versions found within the University of Victoria Special Collections library?

- What does it mean for a book to be forgotten? Furthermore, by producing a collection such as this, what do we remember: the object, or the labour?

By drawing attention to the various stages and actors throughout the production of each collected children's book, I will attempt to continue the process of remembering these "forgotten" children's books: only here, I would like to move away from nostalgia and move into historical recollection. The objective of this exhibit is to present the information found within this book in a variety of uniquely digital ways for the user to form their own interpretative networks.

Portrait photograph of Andrew W. Tuer, British Printer, Vol. IV, No. 34, July–August, 1893: 225–226. Taken from Wikipedia (CC0 public domain license).

Andrew White Tuer

It is difficult to discuss the networks within Forgotten Children's Books without some understanding of Andrew White Tuer. Since the closure of the Leadenhall Press in 1927, little has been written about Tuer or his Leadenhall Press, with some exceptions: a brief 1931 feature in The Monotype Recorder, an article in Book Collector by his godson J.P.T. Bury, and an illustrated bibliography in 2010 by Matthew McLennan Young. By all accounts, Tuer was seen as a visionary figure, whose creative impulses came to define his life and work—positively or negatively, depending on one's opinion of antiquarian printing.

As J.P.T. Bury describes, Andrew White Tuer was born in Sunderland in 1838 to Joseph Robertson Tuer, a partner in a drapery firm, and Jane Taft; his parents passed away during his childhood, whereafter he was sent to live with his great-aunt Ophelia and her husband, Andrew White, after whom he was named (225). Tuer's early life was marked by a series of disillusionments with early career paths, including the seminary in Newcastle and York, and medical school in London. In 1862, he would establish himself as a wholesale stationer with Abraham Field, and the two would continue as Field & Tuer until 1890 (226). Bury notes that Field's involvement in the business is obscure, and little reference to Field was made in references to the press; Tuer was generally viewed as the creative spark behind Leadenhall's success (229-230).

In Field & Tuer, The Leadenhall Press, Matthew McLennan Young documents some of Tuer's many passions, hobbies, and collections:

"his passion for collecting . . . over the years included type specimens, early children's books, specimen covers to novels, 18th century advertising, bank notes, engravings and woodcuts, paintings and drawings, bookplates, china and silver, Christmas cards and valentines, hornbooks, lottery tickets, ornamental alphabets, miniature books and bookcases, silhouettes and samplers, clocks, fashion plates, and trade cards." (11)

In addition, he invented the well-known paste known as “Stickphast,” which, according to Bury, “greatly increased the firm’s prosperity” (230). Such technical and technological innovations seemed to be limited only by the boundaries of Tuer's imagination; as B.J. McMullin writes, "it may not be unfair to characterise Tuer the publisher as a dabbler or dilletante" (158). With much of the prolific output of the Leadenhall Press reflecting Tuer's personal interests—including Forgotten Children's Books—it is difficult to divorce ourselves as readers from the editorial choices of Tuer, even though Tuer suggests no editorialising is taking place. Since most of the books he features in FCB are from his own collection (Tuer 10), we can safely assume that his criteria for inclusion and his aesthetic preferences are closely aligned. By compiling and editing Forgotten Children's Books, which is an extension of his personal preferences, Tuer is helping the reader to remember; but, in doing so, what else has been forgotten?

The cover to Pages and Pictures from Forgotten Children's Books, edited by Andrew W. Tuer. Leadenhall Press, 1899.

The Book as a Material Object

The Cover

The cover of Forgotten Children’s Books features an illustration from “The Adventures of Poor Puss,” written by Miss Sandham, which caricatures a black maid or servant with racially exaggerated features. This is the only such illustration of its type within the book; every other human subject is portrayed as a white European. We must therefore consider why Tuer chose this very particular and extremely racist illustration for the cover of his miscellany.

In his article on African American depictions and illustrations in postcards, Wayne Martin Mellinger delineates mass culture—which imposes cultural values from above—from popular culture, which is “produced by ordinary people who draw upon resources provided by the elites who control the cultural industries” (414). This is a similar dichotomy to miscellanies and anthologies; anthologies and mass culture are similarly theorised to impose value from above, while miscellanies and popular culture are viewed as non-judgmental and representative of cultural practices which appeal to a wider group, often across socioeconomic classes. Mellinger admits that this “largest common denominator is often the lowest common denominator,” and that cultural producers rely upon racist iconography to increase accessibility to the widest possible audience (415-416). Though his survey focuses on African-American caricatures on postcards, it is evident through Tuer’s selection of cover illustration that such depictions were popular with Victorian as well as American audiences across a wide swath of media. Therefore, some qualifiers are necessary to discuss Tuer’s nostalgic network: the books which he deems “forgotten” were very likely produced by white Europeans for white audiences. Recalling Tuer’s objective—how Forgotten Children’s Books is designed to amuse—the nostalgic connections Tuer seeks to create are for those who would see the cover illustration and be amused by that depiction.

But in remembering these books beyond the nostalgic, we must consider how black audiences would have perceived such depictions, and consider how unamusing and dehumanising nature of these depictions. John Henry Adams, an illustrator frequently featured in The Voice of the Negro magazine, wrote as such in 1906: “The caricaturist draws purposely a man’s nose of proportion to the face. There is enough resemblance there for any one to know for whom the picture was intended, but the nose is almost twice as long as it ought to be. . . . No people have felt the sting of the cartoon more than we. Almost in any direction can be seen great wide mouths, thick lips, glaring white eyes . . . These cartoons have no little toward increasing our persecutions and our enemies” (645-646)

As I continue to illustrate the book's obscured networks, it is important to keep in mind how the pursuit of nostalgia can function in exclusionary ways. "When are we ever at home?" Barbara Cassin asks, in her recent exploration of nostalgia as a philosophical and linguistic concept. "When we are welcomed, we ourselves along with those who are close to us" (63). In contrast to this, however, some would find Tuer's choice of cover not welcoming, not amusing, and exclusive rather than inclusive. As you continue through this Omeka exhibit, think about how amusement for some may be exclusion for others, and how amusement and exclusion can (and continues to!) function in innocuous yet parallel ways.

(For further discussion of explicit and implicit racism from children's texts in this time period, see my fellow Omeka exhibitor's page on The Jack of All Trades by D.C. Beard.)

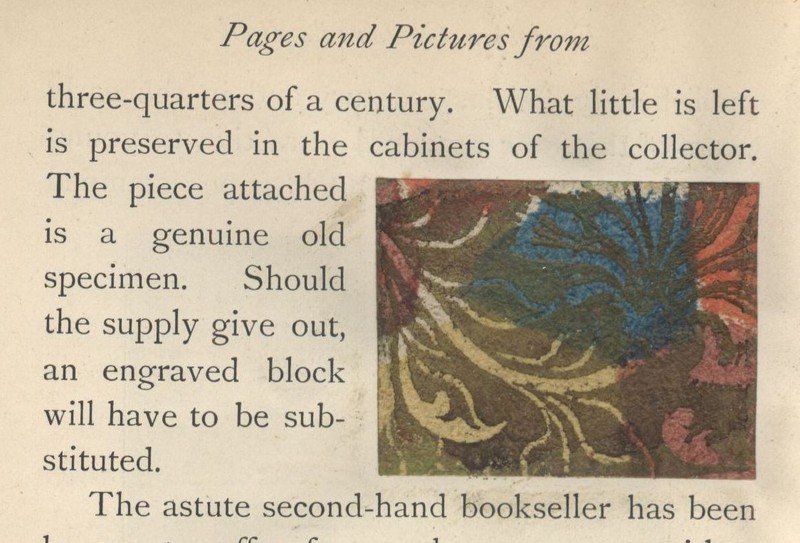

A sample of Dutch paper from the University of Victoria Special Collections copy of Pages and Pictures from Forgotten Children's Books. Every sample was its own unique, individual sample.

This sample is from another copy of Forgotten Children's Books, digitized by the University of Toronto Robarts Library and accessible at archive.org. Note the difference in colour and pattern.

This is the cover to The Cowslip, or More Cautionary Tales in Verse, reprinted by the Leadenhall Press in 1899. The cover features a facsimile of the Dutch paper featured within Forgotten Children's Books.

An advertisement for the Leadenhall Press' "Illustrated Shilling Series," produced at the same time as FCB's publication in 1899. This advertisement came from the back of The Cowslip, as seen above.

The Book as a Material Object

The Dutch Paper

Featured in each copy of Pages and Pictures from Forgotten Children's Books is a "genuine old specimen" of Dutch paper, which was the cover material for many children's books in the early eighteenth and late nineteenth centuries. This paper, as Tuer describes, was "rendered attractive to young eyes . . . with designs in bright colours and gold foil," and "was rather expensive, and has not been made for nearly three-quarters of a century" (7-8). You can view the sample from the University of Victoria's copy of FCB to the top right; below it is a copy from the University of Toronto Robarts Library, which has been digitised and uploaded to archive.org. An additional copy, digitised by Cornell University, also exists on archive.org, but this copy has been scanned in black-and-white, and the space where the sample would be is entirely blank. (Click the links to view these digitised copies on archive.org.)

Note the differences in colour and pattern between the two samples. Presumably, every copy of Forgotten Children's Books would have had a different patch of Dutch paper, rendering each copy individual and unique. The sample from the University of Victoria copy is rough to the touch, with some colour bleed along the top and bottom edge. The sample is firmly adhered to the page with, one presumes, Tuer's own Stickphast glue. This speaks to the exigency of material books, as Tuer provides the reader with physical evidence of how children's books were constructed a century prior. If one were to examine the digitized copy only, the tactile and individual character of the Dutch paper—not to mention Tuer's effort in including it—would be lost.

But think about the source of that Dutch paper. "What little is left," Tuer writes, "is preserved in the cabinets of the collector" (8). Did collectors such as Tuer snatch up the last sources of Dutch paper—perhaps a roll, or some scattered sheets? Or were these samples chopped up from other, older children's book covers and pasted into these books, an act of what my fellow Omeka exhibitor terms "textual cannibalism?" In other words, were other books sacrificed in order to create Tuer's nostalgic network?

An example of this can be found in The Cowslip: or, More Cautionary Stories in Verse, originally printed in 1811 by J. Harris. This book is featured in Forgotten Children's Books, but was also reprinted in whole by The Leadenhall Press as part of their "Illustrated Shilling Series of Forgotten Children's Books," which was published alongside FCB in July 1899 (Young 121). Luckily, the University of Victoria Special Collections Library has a copy of this reprinted edition, which I was able to examine. The cover, which you can view on the right, is not made of Dutch paper but is illustrated as a facsimile of that material. The frontispieces are very similar; I would imagine that this is an example of the "occasional liberties" mentioned in Tuer's introduction (9). The publisher's note to his advertisement at the end of The Cowslip is a condensed version of Tuer's introduction:

The little books printed about a hundred years ago "for the amusement of little masters and misses" must now be looked for in the cabinets of the curious. The type is quaint, the illustrations quainter and the grayish tinted paper abounds in obtrusive specks of embedded dirt. For the covers, gaudy Dutch gilt paper was used, or paper with patchy blobs of startlingly contrasted colours laid on with a brush by young people. The text, always amusing, is of course redolent of earlier days. (69)

In Forgotten Children's Books, Tuer describes the painting process of such covers in greater detail:

The colouring was done by children in their teens, who worked with astonishing celerity and more precision than could be expected. They sat round a table, each with a little pan of water-colour, a brush, a partly coloured copy as a guide, and a pile of printed sheets. One child would paint on the red, wherever it appeared in the copy; another followed, say with the yellow, and so on until the colouring was finished. (7)

So much of children's literature scholarship is preoccupied with how the field can be defined. Among the most influential of these defining works is Jacqueline Rose's The Case of Peter Pan, which argues children's literature is an "impossible" subject where the adult producers of children's literature and the child consumer exist in an asymmetrical power dynamic; children's literature cannot exist because the child has no participation in its creation (1-2). Here, in the production of many children's books within FCB, children directly produce literary material for other children. This is an example of what Marah Gubar describes as Rose's "false assumption that children are a homogenous group that can be straightforwardly defined and addressed" (210). Yet the Victorian period is when Western conceptions of childhood were beginning to be constructed and homogenised. J.S. Bratton calls this "the revolution of the child," where "industrial and social revolutions . . . also focused on [the child's] potential as an instrument of change" (13). Though seemingly minute, the colouring of Dutch paper speaks to the intersection of these revolutions. Burgeoning industrialisation required labour, which, as Tuer tells us, was often found in children; yet children were also recognised as needing literacy, moral education, and social education (Bratton 13-14). The children's books featured within FCB, therefore, become a type of network, linking the multitudinous definitions of children during the nineteenth century.

Geographic Map of Publishers Featured in Forgotten Children's Books

This is a Google map which features the approximate location of the publishers of each featured book within Pages and Pictures of Forgotten Children's Books. The red star represents the Leadenhall Press, while the blue markers represent the various publishers listed in the book. Click on any blue marker to learn more about the books Tuer published in FCB.

Note how two of the most prolific publishers featured within this book have their businesses along major thoroughfares. Darton & Harvey were located on Gracechurch Street, which Lawrence Darton notes was one of the only routes to get to London Bridge (2), while J. Harris was located at the corner of St. Paul's Churchyard, arguably London's biggest and greatest landmark during the early nineteenth century. Harris was cheeky enough to include an advertisement in verse to his printing shop, as found in Dame Partlet's Farm in Forgotten Children's Books:

At Harris's, St Paul's Church-yard,

Good children meet a sure reward;

In coming home the other day

I heard a little master say,

For every penny there he took,

He had receiv'd a little book,

With covers neat, and cuts so pretty,

There's not its like in all the city;

And that for twopence he could buy

A story-book would make one cry;

For little more a book of riddles:

Then let us not buy drums or fiddles,

Nor yet be stopt at pastry-cooks,

But spend our money all in books;

For when we've learnt each book by heart

Mamma will treat us with a tart. (96)

As J.S. Bratton describes, the development in childhood education in the early nineteenth century coincided with burgeoning industrial infrastructure; printers and publishers sprung up to meet this rising demand for children's books (20). We can see this in the map below, as new printers emerged in distant locations from London's core (such as William Darton Jr. in Holborn,) as the city expanded in population and area. Inevitably, a rise in printing and publishing businesses would result in heightened economic competition; we can read the above advertisement as a byproduct of this rising competition. Note how the ideal child reader is directed not to spend their money on games or instruments, but books. If we return to Bratton's idea of the "revolution of the child," which was an awakening in the social and moral potential of children (13), we must also consider how children were being groomed as young consumers, junior participants in the growing capitalist network of London.

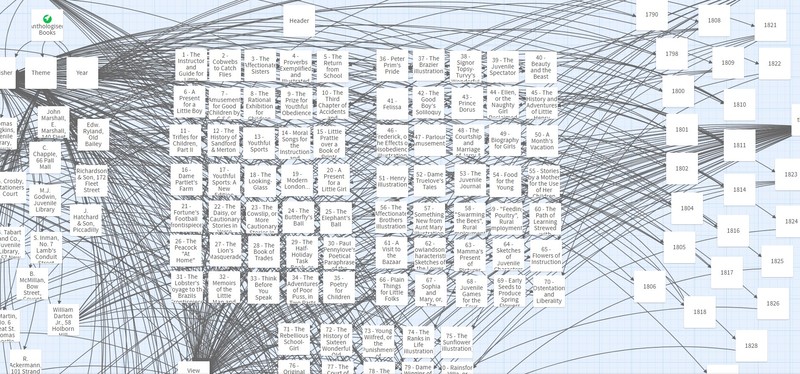

The Forgotten Children's Books

This is an interactive tool for viewing the various children's texts and illustrations by various criteria beyond Tuer's chronological ordering. Users can view the texts by publisher, theme, and year published, if known. If a particular text interests the user, they can add it to their own collection of selected texts, and view the texts they have chosen in the "Selected Texts" page.

The purpose of this tool is to illustrate the networks and labour which brought these children's books and illustrations to life. I have deliberately restricted the navigable categories to "publisher," "theme," and "year," to illustrate to the user the labour, rationale, and context behind the production of each book.

Some examples of collaborative networks can be found between Dean & Munday of Threadneedle Street, and A.K. Newman & Co. of Leadenhall Street. Or consider the generational network between William Darton at 55 Gracechurch Street and his son, William Darton Jr., at 50 Holborn Hill; Darton Jr. was apprenticing at his father's shop and became a partner in 1810 before his father retired the same year (Darton 6).

Thematically, consider the varying strategies these authors employed in their writing to convey instruction. Books such as The Instructor and Guide for Little Masters, found on page 16 of FCB, offer a model of morally proper behaviour, while others such as The Rebellious School-Girl, found on page 389, illustrate disobedience, rudeness, and impropriety, presumably to spur the child reader into obedience. Or note how some texts were not designed as instructional at all: Amusement for Good Children is an excellent example, found on page 37 of FCB.

This is an advertisement for The Leadenhall Press' services, found in the back of Pages and Pictures from Forgotten Children's Books.

This is a screenshot of Twine, the utility used to create the interactive tool found above. The utility provides an interesting visualisation of the networks I have attempted to illustrate. Created by IMW.

Conclusions

Just as Tuer suggested, you, the user, likely scrolled around the map, navigated through the interactive tool, and are ready to put this exhibit back on your mental shelf. Indeed, the objectives of this exhibit and Tuer's volume are perhaps more similar than it may seem. Yet Forgotten Children's Books is designed for amusement, while my objective has been to peel back those layers which might obscure our understanding of this book's hidden networks.

But what has digital remediation accomplished in this case? The geographic map helps to gain an overarching sense of the publishers and consumers in London and beyond; the tool helps to make thematic and labour connections between the various books and producers found within. My attempt to "digitise" the networks of these books went beyond merely scanning and uploading the scanned files for others to read. The possibility exists within digital media to repurpose and reillustrate the networks and the data of a book in creative and illuminating ways. Yet, inevitably, more can always be illustrated or elucidated. For example, the economics of these books—or what the price of these books can tell us about their production and their target audience—is an interesting point of inquiry, but beyond the scope of this exhibit.

Also note how digitization can miss physical details, such as the Dutch paper mentioned above. Such physical details can direct us to paths of research which digitization can never offer. It is worth mentioning how multiple digital copies of this text either undermine or ignore the special paper pasted within; only by holding the physical book in my hands was I able to speak to this inclusion.

Tuer was right when he said of children's books: "the material is so great that in a single volume . . . the fringe only can be touched" (8). Like Forgotten Children's Books, it is best not to read this exhibit as an exhaustive attempt to document every actor included within; rather, this exhibit is best experienced as an introduction to the multitude of research possibilities presented by the physical and thematic characteristics of a singular book. In thinking of Forgotten Children's Books as a network, we can find links to myriad other children's books—across genres, across time, between publishers, authors, and illustrators—that are waiting to be explored.

Bibliography

Adams, John Henry. "McGowan's Cartoons." The Voice of the Negro, vol. 3-4, September 1906, pp. 645-649. Hathitrust, catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/006784893.

Bradford, Clare. “The Case of Children’s Literature: Colonial or Anti-Colonial?” Global Studies of Childhood, vol. 1, no. 4, Dec. 2011, pp. 271–79. Crossref, doi:10.2304/gsch.2011.1.4.271.

Bratton, J.S. The Impact of Victorian Children's Fiction. Croon Helm, 1981.

Bury, J. P. T. “A.W. Tuer and the Leadenhall Press.” Book Collector, vol. 36, no. 2, 1987, pp. 225-243.

Cassin, Barbara. Nostalgia: When Are We Ever At Home? Fordham University Press, 2016.

Clair, Colin. A History of Printing in Britain. Cassell, 1965.

Darton, Lawrence. "William Darton (1799-1819), Author, Illustrator, and Publisher of Children's Books." Boys and Girls House, Toronto Public Library, April 30 1992. Lecture.

Groth, Helen. Victorian Photography and Literary Nostalgia. Oxford University Press, 2003.

Gubar, Marah. “On Not Defining Children’s Literature.” PMLA, vol. 126, no. 1, 2011, pp. 209–16. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41414094.

Monotype Corporation. "The Fifty Best Books of 1931." Monotype Recorder, vol. 30, no. 241, 1931, pp. 3-12.

Rose, Jacqueline. The Case of Peter Pan: or The Impossibility of Children’s Fiction. Palgrave Macmillan UK, 1984. Springer Link, doi:10.1007/978-1-349-17385-3_1.

Suarez, Michael. "The Production and Consumption of Eighteenth-Century Poetic Miscellany." Books and their Readers in Eighteenth-Century England: New Essays. Edited by Isabel Rivers, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2003, pp. 217-252. ProQuest Ebook Central, ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/uvic/detail.action?docID=436856.

Tuer, Andrew W., editor. Pages and Pictures of Forgotten Children's Books. Leadenhall Press, 1899. (Special Collections Call Number: Z1037 T92)

Tuer, Andrew W., editor. Stories from Old-Fashioned Children's Books. 1900. Singing Tree Press, 1968.

Turner, Elizabeth. The Cowslip: or, More Cautionary Stories in Verse. 1811. Leadenhall Press, 1899.

Young, Matthew McLennan. Field & Tuer, The Leadenhall Press: A Checklist with an Appreciation of Andrew White Tuer. Oak Knoll Press, 2010.

IMW / Fall 2018.