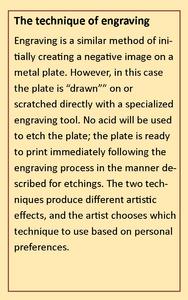

Bentley's Miscellany (1838)

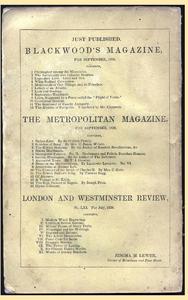

Front cover, Bentley's Miscellany, Vol. XXI, September 1, 1838, New York edition, Jemima M. Lewer publisher.

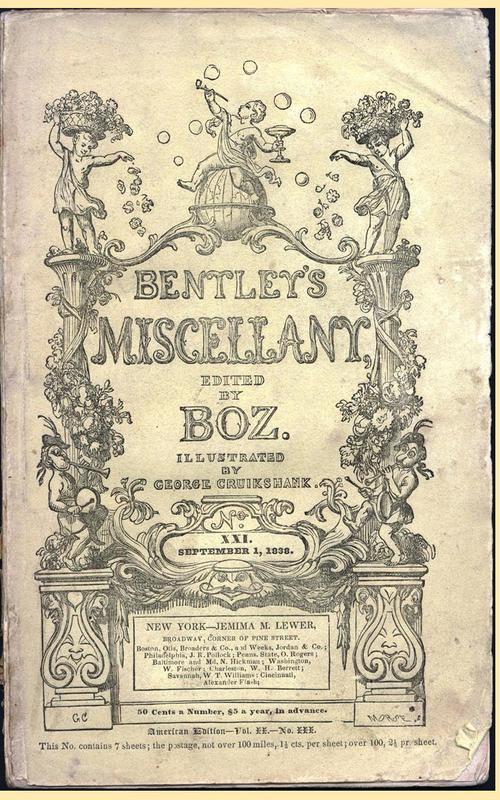

Detail from the inner page shown opposite. Book owners at this time often set inscriptions like this to establish ownership in the event the item were loaned and not returned, or otherwise lost or stolen. An inner inscription was often in addition to a primary one that appeared in the front matter, as is the case here (primary inscription shown above).

I. Introduction

Bentley's Miscellany is an excellent example of early Victorian periodical art published primarily by Richard Bentley between 1837 and 1868.

Released monthly in paper-bound single issues and also semi-annually in hardbound compilations, Bentley's is a precursor to subsequent "miscellanies," such as Household Words and All the Year Round, which featured diverse material ranging from fiction to poetry to criticism to travelogue, and more. Bentley's is especially interesting as an example of a "collaborative" artistic and commercial venture between publisher (Bentley), editor (initially Charles Dickens), illustrators (George Cruikshank et al.), and many different contributors.

Richard Bentley had been in a partnership with Henry Colburn, producing the popular Standard Novel Series that issued relatively inexpensive sets of well-known works of literature from the recent past. After Bentley split with Colburn, he established his own publishing house and began to conceive of a monthly periodical as a vehicle to promote his publications. Bentley soon began to focus on the then-relatively unknown Charles Dickens as a potential first editor. Dickens had only recently achieved notice for his Sketches by Boz (published serially in various newspapers and periodicals between 1833 and 1836 and collectively in 1839 by Chapman and Hall) and The Pickwick Papers (published in shilling installments between 1836 and 1837 and collectively in 1837 by Chapman and Hall), and the early days of his rising star power made him a desirable and relatively low-cost choice for Bentley. Bentley offered Dickens £500 for his next novel, Oliver Twist, with further remuneration for the serialization, and a salary for agreeing to serve as first editor of the new magazine while also contributing 15 pages of his own material to each issue (Patten 75). Although the salary was ultimately never sufficient to keep Dickens happily employed, it nevertheless sufficed to launch Bentley's Miscellany in January 1837.

Bentley's Miscellany and the University of Victoria, Special Collections

Special Collections was able to acquire a single issue of the periodical through a private bookseller as part of a larger private collection that was donated to the university (donation date unknown). The particular issue housed in Special Collections is the American edition of Bentley's Miscellany, published in New York by Jemima M. Lewer, as Vol. II, No. III. The corresponding London edition was No. 21 dated 1 September 1838. The cover image shows that the volume is well worn—it will soon be 200 years old!—and therefore it is somewhat fragile.

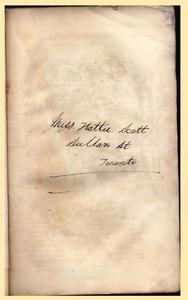

Inscription

As shown in the image opposite, one of the pages in the front matter has been inscribed, presumably by the original owner, as follows: "Miss Hattie Scott / Sullan St / Toronto." Such inscriptions tend to indicate a love of books and pride in ownership. If lost, the owner has indicated how it might be returned. Fond book owners often inscribed inner pages, as well, which served as an added security measure in the event that the front page might be torn out by a book thief. The inner inscription would hopefully survive to allow the owner to reclaim the treasured book. In this case, Miss Scott has also inscribed an inner page beside one of Cruikshank’s etchings.

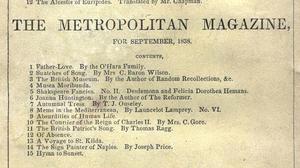

Further Offerings from the Publisher

Publishers of periodicals such as Bentley's Miscellany often used the space in back covers and/or inside covers to advertise further offerings of their periodicals. Because this particular edition of the journal is published in New York, the back cover (shown above to the right) shows the offerings available from publisher Jemima M. Lewer ("Corner of Broadway and Pine Street") rather than from Bentley, who was the primary publisher in England.

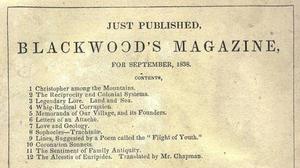

Table of Contents, Bentley's Miscellany, Vol. XXI, September 1, 1838, New York edition, Jemima M. Lewer publisher. Image scan by Peter Wilson, courtesy of Special Collections, University of Victoria.

II. The "Collaboration"

Bentley, Boz, and Cruikshank stand

Like expectant reelers;

"Music!" "Play up!" pipe in hand

Beside the fluted pillars

Boz and Cruikshank want to dance,—

None for frolic riper;

But Bentley makes the first advance,

Because he pays the piper.

A satirical song credited to Maginn, inspired by George Cruikshank's design for the magazine's wrapper, entitled "The Song of the Cover," from a proposed larger work entitled "The Bentley Ballads" (cited in Kitton 9).

A wide variety of writers contributed to Bentley's Miscellany, but most were not credited for their work. The name "Boz," however, always appeared prominently during the first two years, both on the cover, where it was associated with the role of editor, and in the Contents, associated with the role of writer and contributor of the set-piece serialized novels.

In the single edition held in Special Collections at the University of Victoria, the name "Boz," a.k.a. Charles Dickens, appears prominently associated with his contribution, "Full Report of the Second Meeting of the Mudfog Association for the Advancement of Everything." The tendency to credit his own work but not the work of others is characteristic of Dickens's editorial control. As Lillian Nayder points out, the approach to authorial control that Dickens demonstrated in Bentley's Miscellany and carried forward into his later magazines, which is characterized by his insistantance "that the writings of his contributors appear anonymously, under a masthead that read ['edited by "Boz"' and later] 'Conducted by Charles Dickens,' [gave him the ability to market] his own name rather than theirs" (2).

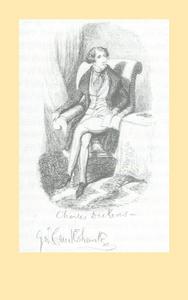

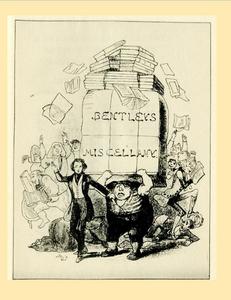

Authors who did receive credit from "Boz" in the Special Collections issue, although occasionally with tongue in cheek, include W. B. Le Gros for "Cupid and Jupiter. A Fable"; Mr. Buller of Brazen Nose for "Walter Childe"; Captain Medwin for "Pasquale; A Tale of Italy"; Mr. Buller again for "Anacreon Made Easy"; and C. J. Hoffman for "A Night on the Enchanted Mountains." "A Chapter on Gourmanderie" is attributed only to the author of "A Parisian Sabbath." While the current custom of giving full credit to authors did not apply in Dickens's time, it is noteworthy that in any of the periodicals that Dickens was involved with throughout his career, his identifying moniker always appears prominently. Illustrator Hablot K. Browne's caricature of Charles Dickens as editor of Bentley's Miscellany shortly after its launch and instant success, depicts Dickens's attitude as he leads an overworked porter carrying a huge consignment of the magazine above his head: they wade through a crowd snapping up copies of the magazine that fall from the top of the heap.

Dickens's "Collaboration" with Bentley

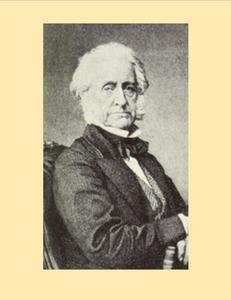

Richard Bentley, Publisher

Richard Bentley, who lived from 1794 to 1871, learned the trade of printing from his uncle and later formed a high-quality printing company with his older brother Samuel. In 1829, Bentley entered into a publishing partnership with Henry Colburn and launched the Standard Novels series. By 1831, Bentley was no longer prepared to remain in partnership with Colburn, largely as a result of Colburn’s extreme indebtedness. Bentley purchased Colburn’s share of the business in return for an agreement that Colburn would not publish any new books within 20 miles of London.

Bentley was first and foremost a businessman and sought ways to successfully market his publications and maximize profits. Unfortunately, Bentley’s business habits eventually clashed with Dickens’s expectations for remuneration and control, and, although Bentley made continual attempts to placate Dickens and keep him on as editor, Dickens finally resolved to break his contract. Bentley might have successfully sued Dickens for breach of contract but never did so. To some, this might seem like an act of generosity, but it was most likely only a business decision to avoid negative public opinion associated with being the publisher who sued a beloved author.

Dickens as Editor, 1837-1838

As mentioned previously, Dickens had been a relative unknown when he first entered into contract with Richard Bentley. Although a "relative" no-name, his star was beginning to rise, and the serialization of Oliver Twist in the first issues of Bentley's Miscellany, paired with the striking satirical illustrations by George Cruikshank that were a perfect match with Dickens's writing style, soon propelled Dickens to the height of popularity among readers in London and New York. However, Dickens's sense of his own worth was never matched by the remuneration that Richard Bentley was prepared to offer, and consequently the financial arrangement remained a point of conflict between the two men throughout Dickens's tenure as editor.

At the same time, Dickens always wanted more editorial control, maintaining that the magazine was in every way "Bentley's" miscellany. Even so, Dickens was the man responsible for commissioning articles, and his personality seems virtually embossed on every page of the magazine. Perhaps Robert L. Patten best sums up the editorial dispute between Dickens and Bentley as follows:

Two major areas of friction can be distinguished. First, Dickens found Bentley’s interference in the editorial policy of the Miscellany annoying. Dickens’s duties as editor were defined by the second of nine Agreements with Bentley made on 4 November 1836: to correspond with contributors, read all submissions and “give his judgment upon their eligibility,” revise and correct all articles accepted, furnish the printer with enough matter for six sheets demy 8vo by the twenty-fourth of every month, and correct proof. Bentley retained the right to veto the insertion of any article, and this he gradually extended into co-editorship. (75)

The second major area of friction, of course, was Dickens’s aforementioned concern about remuneration. As Tomalin points out, Dickens revealed the extent of his feelings in the matter when he ultimately referred to Bentley as an "infernal, rich, plundering, thundering old Jew"—quoting his own dialogue from Oliver Twist that is hurled at Fagin by none other than Bill Sikes (Tomalin 71).

On the one hand, Dickens’s concern about remuneration is understandable; he is concerned for an author's right to receive a fair share of the publisher's profits. On the other hand, there is evidence that he was never entirely innocent or honest in his dealings with his publishers. As Claire Tomalin points out in Charles Dickens: A Life, "If Dickens is to be believed, each publisher started well and then turned into a villain; but the truth is that, while they were businessmen and drove hard bargains, Dickens was often demonstrably in the wrong in his dealings with them" (70).

Dickens as Writer and Contributor, 1837-1838

Dickens's role as editor was likely always a secondary one for him, even though he performed it as diligently as possible, and even though the editor's job is clearly key within any publication. For Dickens, the two roles, writer and editor, were always in some degree of conflict, especially since he was not an owner. The primary focus of Dickens's involvement with Bentley's was to see that his novels were serialized as the main event. However, Dickens's objectives in promoting his work generally worked in tandem with his objectives as editor, when he felt he had the freedom to pursue them. As Juliet John points out, "Dickens must have been the first novelist to consciously cultivate the idea of a cross-class 'íntimate public' in order to bond a mass readership.... [T]he fantasy of an intimate public offers even those alienated from politics feelings of agency and belonging, a sense of 'reciprocity otherwise absent in the world'" (5).

Ironically, though, the very success that Bentley's Miscellany contributed to Dickens's writing career through serialization ended up as the cause of chronic irritation between author and publisher, mainly as a result of Dickens's growing sense of self-worth. Dickens became so frustrated with the financial arrangement in his contract with Bentley while in the midst of serializing Oliver Twist that he threatened to break off writing the novel altogether (Tomalin 93). In the end, Dickens did break his contract with Bentley, and in no uncertain terms, as the following excerpt from The Selected Letters of Charles Dickens demonstrates:

[I am conscious] that my books are enriching everybody connected with them but myself, and that I, with such a popularity as I have acquired, am struggling in old toils, and wasting my energies in the very height and freshness of my fame, and the best part of my life, to fill the pockets of others, while for those who are nearest and dearest to me I can realise little more than a genteel subsistence.... I do most solemnly declare that mortally, before God and man, I hold myself released from such hard bargains as these, after I have done so much for those who drove them. This net that has been wound about me, so chafes me, so exasperates and irritates my mind, that to break it at whatever cost ... is my constant impulse. (Hartley 50)

Perhaps one of Dickens's legacies, which he established while working on Bentley's Miscellany and through clashing with his publisher over remuneration is, as Lillian Nayder observes, "proving that novel writing could be a lucrative, middle-class profession and ... demonstrating just how profitable fiction could be when it was serialized and mass produced" (1).

The Parting of Ways

After accusing Bentley of "offensive impertinence" in his negotiations to keep him, Dickens persuaded his colleague Harrison Ainsworth to step in as editor of the magazine and immediately resigned from it himself (Tomalin 101). At age 25, Dickens had gone far in his career, and his success had burgeoned while with Bentley's. At age 27, now quit of Bentley's—and of Bentley—for good, his already high-soaring star was still early in its ascension.

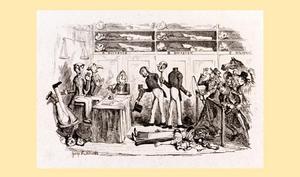

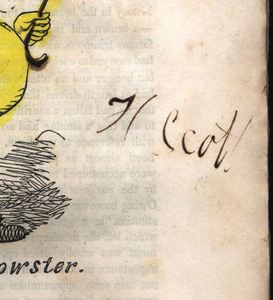

Etched illustration for The Mudfog Papers: "Sir Isaac Newton's Courtship," New York, Jemima M. Lewer publisher, 1 September 1838. Image scan by Peter Wilson, courtesy of Special Collections, University of Victoria.

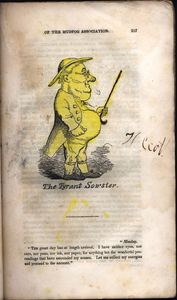

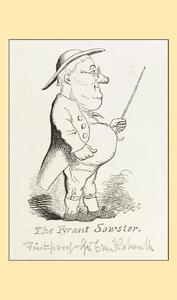

Etched illustration for The Mudfog Papers: "The Tyrant Sowster," New York, Jemima M. Lewer publisher, 1 September 1838. Image scan by Peter Wilson, courtesy of Special Collections, University of Victoria. Evidently the image was hand-colored at some point during ownership. This page is also inscribed, presumably by the original owner, who also inscribed one of the pages in the front matter.

Cruikshank's etching, "The Tyrant Sowster," as it would have been reproduced originally, without the hand-coloring evident in the previous image from the edition used for this exhibition. Note that Cruikshank has documented this edition as, "First Proof," followed by his signature. Image courtesy of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

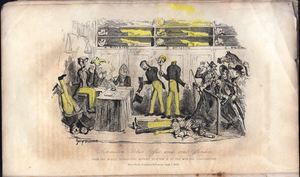

Etched illustration for The Mudfog Papers: "Automaton Police Office and real Offenders," New York, Jemima M. Lewer publisher, 1 September 1838. Image scan by Peter Wilson, courtesy of Special Collections, University of Victoria. Evidently the illustration was hand-colored at some point during ownership.

III. The Illustrations

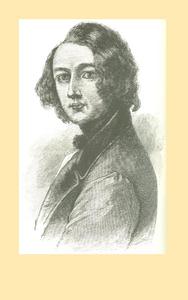

George Cruikshank

Cruikshank was a British caricaturist and book illustrator, who lived from 1792 to 1878. His book illustrations for his friend Charles Dickens, and many other authors, reached an international audience. He was praised as the "modern Hogarth" during his life and was the first illustrator to work with the unknown "Boz" on his Sketches by Boz (Cohen 15). Cruikshank had been specifically chosen by Richard Bentley as one of the key illustrators of the Miscellany throughout its history.

Cruikshank's Stature as an Illustrator

In Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators, Jane R. Cohen succinctly sums up Cruikshank's reputation and status as an artist: "That Cruikshank, son and brother of artists, was the undisputed heir of Hogarth, Gillray, and Rowlandson was already a commonplace observation. His early satirical prints on political and social topics of the day, for which he conceived as well as designed characters, plot, and dialogue, were so popular in the London of Dickens's youth that the Crown paid him not to caricature the King; his book illustrations in the 1820s and 1830s for authors, living and dead, were classics before anyone ever heard of Boz" (15).

Cruikshank and Dickens

For Charles Dickens, Cruikshank illustrated Sketches by Boz (1836), The Mudfog Papers (1837–38) and Oliver Twist (1838), the latter two works being serialized in Bentley's Miscellany during Dickens's tenure as editor. As Michael Steig points out, "[I]t is by now well known that Dickens took great pains over the illustrations to his works, and that they must be considered essential to a full reading [of his works]" (220). As Steig further notes, the historical predecessors to Dickens's novels are works in which the letterpress was subordinate to the engravings or etchings (220). In other words, narratives were based on the illustrations, and not the other way around as in Dickens's work. This is an important point to keep in mind in relation to the eventual argument that takes place between Cruikshank and Dickens over authorship in Bentley's serialized novels, including Oliver Twist (Kitton 17-24).

Cohen aptly characterizes the working relationship between Cruikshank and Dickens as "a struggle for sovereignty" (15). Because Cruikshank had been selected by publisher Bentley, Dickens had no choice but to work with him (20). Dickens's behavior in working with Cruikshank is consistent with his other behavior in "collaborative" projects: he desires nothing less than total control. Moreover, he clearly felt that any illustrations of his work must be considered subordinate to the text. However, as Cohen points out, "Cruikshank [was] a member of the old school of fiercely independent artists [and] chaffed in any subordinate role" (17). The two men's art complemented each other perfectly in their satirical style: If Cruikshank was the contemporary Hogarth, Dickens was the literary equivalent, the Hogarth of the written word (18). As Cohen notes, "Dickens described the appearance of his characters as well as their environment in graphic detail. Yet the physical attributes of his characters, as Thackeray observed, would not have 'ímpressed' themselves on the reader's memory were it not for Cruikshank's rendering of them'' (18). Therefore, despite their differences, the collaboration between illustrator, author, and publisher produced enormously successful results for everyone concerned, and the publication of Sketches by Boz in 1836 revealed none of the tense back story to its production. Yet the tension continued into subsequent work that was serialized in Bentley's Miscellany, including Oliver Twist and The Mudfog Papers.

As Dickens's star continued to rise, Cruikshank's began to decline, and the two men seldom worked together after their experience at Bentley's. Throughout his life, Cruikshank harbored deep resentment about the "collaboration" with Dickens on Oliver Twist. According to Cohen, evidence from that time indicates that "the real extent of the artist's participation in the novel [was] that of an active but frustrated colleague"(38), yet Cruikshank never felt he received the credit (or remuneration) he was due. Eventually, in the last years of his life, Cruikshank increasingly voiced his dissatisfaction with the record of events and attempted to set it straight (Waugh 26). In 1871 he published a letter in The Times that claimed credit for much of the plot of Oliver Twist (Kitton 19). The letter launched a fierce controversy around who created the work that remains unresolved to this day.

Cruikshank's Legacy

The Dictionary of Nineteenth-century Journalism in England and Ireland accredits Cruikshank as "the most celebrated comic artist of the early and mid-Victorian periods" (Brake and Demoor 155). Cruikshank's most prestigious magazine illustrations appeared in the pages of Bentley's Miscellany (155). In his lifetime Cruikshank created nearly 10,000 prints, illustrations, and plates. There are collections of his works in the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum. A Royal Society of Arts blue plaque commemorates Cruikshank at 293 Hampstead Road in Camden Town.

"The Second Meeting of the Mudfog Association for the Advancement of Everything": The second installment of Dickens's The Mudfog Papers.

IV. The Mudfog Papers

The Greatest Dickens Novel You've Never Read

by "Boz" a.k.a. Charles Dickens; illustrated by George Cruikshank

Bentley's Miscellany published the material that came to be known as The Mudfog Papers in serial form from 1837 to 1838, while Dickens was serving as editor. The collected Papers were not published until 1880, long after Dickens had parted company with publisher Richard Bentley.

The single issue of the magazine held in Special Collections at the University of Victoria contains the installment titled "Full Report of the Second Meeting of the Mudfog Association for the Advancement of Everything."

The Mudfog Papers relates the proceedings of the aforementioned fictional association, which is a satirical, Pickwickian treatment of the various learned societies in existence at that time (Cohen 20). Like The Pickwick Papers, The Mudfog Papers claims affinity with parliamentary reports, memoirs and posthumous papers. The work's fictitious Society is a presumed parody of the newly founded British Association (Hobsbaum Appendix I).

The fictional town of Mudfog was based on Chatham in Kent, where Dickens spent part of his youth (Horne 486). When Oliver Twist first appeared in Bentley's Miscellany in February 1837, Mudfog was described by Dickens as the town where Oliver was born and spent his early years, making Oliver Twist a continuation of The Mudfog Papers, but this allusion was removed when the novel was published as a book (486).

At the conclusion of his first contribution, about the mayor of the provincial town of Mudfog, Dickens explains that "this is the first time we have published any of our gleanings from this particular source," referring to The Mudfog Papers (Bentley's Miscellany, vol. 4, no. 20). He also suggests that "at some future period, we may venture to open the chronicles of Mudfog" (Horne 486).

The contents of the 1880 edition of The Mudfog Papers, Etc. published by Bentley and Son included the following texts: "Public Life of Mr. Tulrumble, Once Mayor of Mudfog," "Full Report on the First Meeting of the Mudfog Association for the Advancement of Science," "Full Report of the Second Meeting of the Mudfog Association for the Advancement of Everything," "The Pantomime of Life," "Some Particulars Concerning a Lion," and "Mr. Robert Bolton, the 'Gentleman Connected with the Press.’"

Ultimately, the collected Mudfog Papers is exemplary of Dickens's early minor work, heavy with satire and humour giving rise to light social commentary. The collected pieces are easy to read and highly entertaining, with the expected Dickensian nomenclature and phraseology. While The Mudfog Papers as a collected work does not amount to one of the greatest works by Dickens in his long and illustrious career, it is very likely to amount to the greatest Dickens novel you've never read. Happily, this situation is easily remedied by looking up the early issues of Bentley's Miscellany online (at Google Books, for example) or by acquiring the collected Mudfog Papers at a library or bookseller near you. For those fortunate enough to reside in Victoria, British Columbia, there is a special treat awaiting you in Special Collections at the UVic Library.

V. The Sources

Works Cited

Bentley’s Miscellany, No. XXI, 1 September 1838 (US edition, Vol II, No. III), published by Jemima M. Lewer, New York.

Brake, Laurel, and Marysa Demoor, eds. Dictionary of Nineteenth-century Journalism in Great Britain and Ireland. Academia Press, 2009.

Cohen, Jane R. Charles Dickens and His Original Illustrators. Ohio State UP, 1980.

Dickens, Charles. The Mudfrog Papers, Etc. Richard Bentley and Son, 1880.

Hartley, Jenny. The Selected Letters of Charles Dickens. Oxford UP, 2012.

Hobsbaum, Philip. A Reader’s Guide to Charles Dickens. Syracuse UP, 1972.

Horne, Philip, ed. Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist, or, The Parish Boy's Progress. Penguin Classics, 2003.

John, Juliet. Dickens and Mass Culture. Oxford UP, 2010.

Kitton, Frederic G. Dickens and His Illustrators: Cruikshank, Seymour, Buss, “Phiz,” Cattermole, Leech, Doyle, Stanfield, Maclise, Tenniel, Frank Stone, Landseer, Palmer, Topham, Marcus Stone, and Luke Fildes. George Redway, 1899.

Matz, B.W., ed. Dickens in Cartoon and Caricature, compiled by William Glyde Wilkins, privately printed exclusively for members of the Bibliophile Society, Boston, 1924.

Nayder, Lillian. Unequal Partners: Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, and Victorian Authorship. Cornell UP, 2002.

Patten, Robert L. Charles Dickens and His Publishers. Oxford UP, 1978.

Steig, Michael. “Dickens, Hablôt Browne, and the Tradition of English Caricature.” Criticism, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 219-33.

Tomalin, Claire. Charles Dickens: A Life. Penguin, 2011.

Waugh, Arthur. "Charles Dickens and His Illustrators." Nonesuch Dickensiana. Nonesuch Press, 1937.

Works Consulted

Cordery, Gareth. An Edwardian’s View of Dickens and his Illustrators: Harry Furniss’s “A Sketch of Boz.” ELT Press, 2005.

Harvey, John R. Victorian Novelists and Their Illustrations. Sidgwick and Jackson, 1970.

Hatton, Thomas, and Arthur H. Cleaver. A Bibliography of the Periodical Works of Charles Dickens. Chapman and Hall, 1933.

Hughes, Linda K. “Inventing Poetry and Pictorialism in Once a Week: A Magazine of Visual Effects.” Victorian Poetry, vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 41-72.

Steig, Michael. “Dickens and Browne: Illustration, Collaboration, and Iconography.” Victorian Web. November 2009. Accessed 1 December 2016.

Reed, John R. "Emblems in Victorian Literature," Hartford Studies in Literature, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 19-39.

Sutherland, John. The Longman Companion to Victorian Fiction, 2nd ed. Routledge, 2013.

PW/Fall 2016