Melanie Aguila and Stephen Perry (ed.), Femzine (c.1991)

Table of Contents

I. Introduction and Methods of Inquiry

II. Materiality of Femzine

III. Individual Agency in Networks of Collective Resistance

IV. In Depth Analysis: Creeps in the Streets

V. Further reading and links to social movements

VI. Acknowledgements

VII. Works Cited

I. Introduction and Methods of Inquiry

The word ‘zine’ is a variant of the term fanzine, which was originally used to refer to self-published magazines, usually for fans of science fiction (Radway 140). Janice Radway, a well-known zine scholar, defines zines as “handmade, non-commercial, irregularly issued, small-run, paper publications circulated by individuals participating in alternative, special-interest communities” (Radway 140). According to Mike Gunderloy and Cari Goldberg Janice, “generally, they’re created by one person, for love rather than money, and focus on a particular subject (Gunderloy and Janice 2). There is no clear count of how many zines there are, but based on certain estimates by scholars who study them, there are around 20,000 zines in existence (Gunderloy and Janice 3).

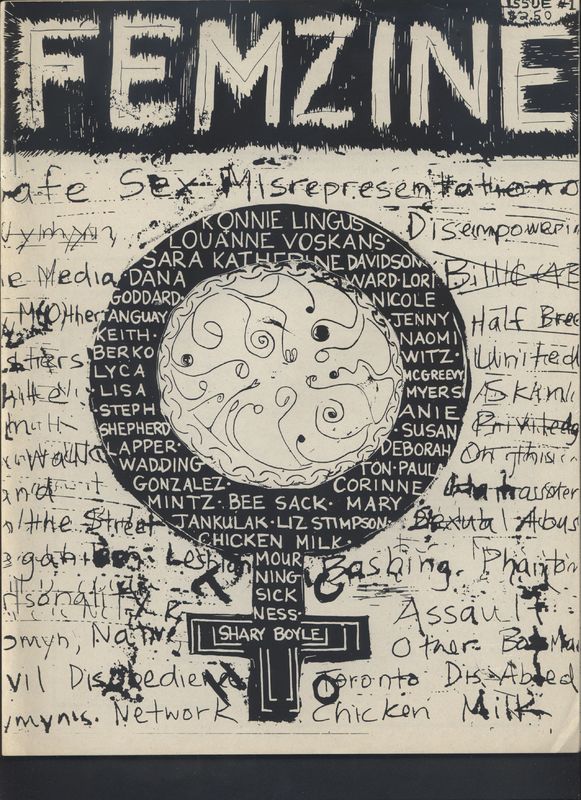

This page explores Femzine— a feminist zine published in Toronto around 1991 and focuses on its role in movements of social and political justice. Not much is known about its history, only that it was published around 1991 and is the first issue in what was meant to be a series of publications. There is a call for submissions in the zine but based on the information in Special Collections, it stopped being published sometime during the 1990s. It was gifted to the University of Victoria Special Collections by Sam Wager as a part of the anarchist archive in 2002. Its call number is HQ 1104 F45.

With this background in mind, this page investigates the place of Femzine in media history and through a combination of textual and media studies. it also focuses on its materiality, both as a bound print object and when it is remediated digitally. In addition to this, it examines its role in creating networks between the artists in the zine, with other zinesters and with those involved in social justice movements at large. Following scholarship specific to zines by authors such as Stephen Duncombe, Janice Radway, and Rosemary Clark-Parsons I will research the defiant aspect of Femzine embodied by the material of it and demonstrate that it allows room for the representation of multiple feminisms within a collective network. Finally, by linking to projects related to the zine in the further reading section, this page attempts to encourage active engagement with feminist issues in society.

In keeping with the performative aspect of zines as being inherently charged with action, this page is meant to be engaged with critically, not absorbed passively. What does it mean to remediate Femzine digitally? For instance, many zinesters prefer to remain untraceable and to circulate their zines only to a handful of people within their community. Others prefer not to have a presence on mainstream platforms because they worry about being co-opted by mainstream media to suit their needs (Chu 77). In this light, what does it mean to remediate Femzine online without the consent of its creators? Additionally, zinesters emphasise their messiness and the lack of any copyright ownership as integral components of a zine (Chu 78). Does this make the linear organization of this page and the copyright information included in the metadata disrespectful to the zinesters who put it together? If so, what are the alternatives?

In the following sections, I begin by exploring the materiality of Femzine both as a print object and its digital form. For the next block, I delve into the social and political networks of resistance it creates both within and outside of the zine. Following that I give an analysis on one piece in the zine: a four-panel comic by Lisa Myers titled “Creeps in the Street”. This is followed by a gallery of art and photographs from the rest of the zine, to give the reader an idea of the diversity of the content. The final sections of this Omeka page include suggestions for further reading, acknowledgements, and a works cited list.

II. Materiality of Femzine

“Zines instigate intimate, affectionate connections between their creators and readers, not just communities but what I am calling embodied communities, made possible by the materiality of the zine medium.” (Peipmeier 58)

* * *

As a print object, Femzine is a collection of twenty-eight pages bound by two staples and printed on both sides. It costs $2.50 and is a combination of collages, drawings and scribbles; most of the writing is hand-written, with very few pages of typed material. As such, it lies on the cusp of being bound and unbound; unlike a novel, if one of the pages were torn off, very few individuals would notice. This is perhaps the most belittled characteristic of zines; as noted by Chris Dodge in the Wilson Library Bulletin, “notorious for their ephemeral nature, criticised for their sloppy production values and dubious credibility self-published magazines [are considered to be] a nuisance, at best, and more generally are ignored altogether” (Dodge 26). However, this difficulty in tracing a zine is considered to be a strength by others; for instance, in her book Future Girl: Young Women in the Twenty-First Century Anita Harris highlights how “[zines] constitute in-between spaces and, as a result, are potentially ideal locales for the creation of narratives that disrupt hegemonic discourses about young womanhood” (156). This holds true of Femzine; I tried searching the names of some of the artists and art projects online but couldn't find them. Harris sees this as a plus; because zines are difficult to place, especially by mainstream media, they are also difficult to regulate, thus allowing zinesters, particularly young girls to express themselves as they see fit.

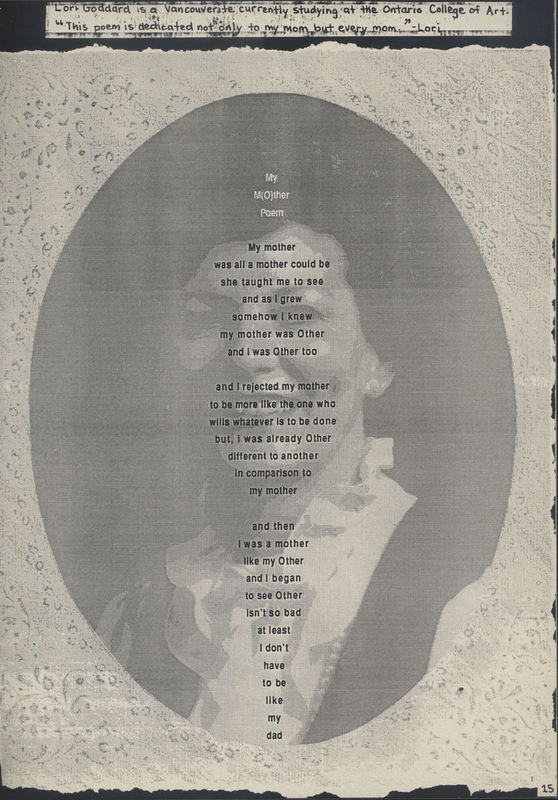

Zinesters also pride themselves on their do-it-yourself aesthetic and in keeping with this spirit Femzine consists of a messy combination of drawings, collages and pictures. The front cover is an example; it has the female gender symbol on it in bold ink with the names of the contributors written inside of it and with words like “disempowering”, “bashing” and “misrepresentation” scribbled all around it. By filling up the entire page, this image asserts the right of all of these women to speak up about their experiences within the collective network that the zine creates. The varying and messy typography of the scribbled words has a dramatic effect and adds to the above assertion. This also gives the reader a strong sense of what they are about to read before even opening the zine. Another example of an interesting layout is in the poem My (M)Other by Lori Goddard (15). The poem is about Goddard’s own internalised discrimination against both herself and her mother for being “Other” and her coming to terms with her childhood anxieties for feeling socially alienated based on her identity. The layout of this page is in a collage format: a page with intricate decorations is pasted over a plain black page and the poem itself is pasted over a picture of a woman, possibly the poetesses mother. This collage has an unrefined quality to it: the edges of the picture are not exactly oval and the border of the paper on which the picture is stuck is also uneven; it looks like it was torn by hand and stuck on the base. This messiness on the page conveys an intimacy; the reader knows on looking at it that it was not mass-produced in a factory. In the case of this poem, its vulnerability is also the author’s feelings of insecurity as she coped with feeling isolated during her childhood.

The handmade quality of Femzine is an important aesthetic common to zines in general. As mentioned by Stephen Duncombe, “[zinesters] redefine work, setting out their creative labor done on zines as a protest against the drudgery of working for another’s profit” (183). Alison Peipmeier comments on this as well in her book Zines: Making Media, Doing Feminism when she says,

“The handwriting of the author is often incorporated into the zine, as are the rough edges left by scissors and the lines of tape holding pieces of text and imagery to the page. The zinester’s body — the actual physical acts that went into creating the zine — is thus visible, and this creates not only what Duncombe calls “a style of intimate connection” but also a kind of corporeal connection, one that brings together the body of the zine creator and the body of the reader. Most zine creators reject the commercial aesthetic because they reject the ideology of commercial mass media; rather than positioning readers as consumers, as a marketplace, the zine positions them as friends, equals, members of an embodied community who are a part of a conversation with the zine maker, and the zine aesthetic plays a crucial role in this positioning.” (Peipmeier 70)

This importance of the do-it-yourself aesthetic raises a question: is it possible to respect the handmade quality of the zine and the reasons for doing so while remediating it digitally? There is no simple answer to this and it is important not to romanticize either analog or digital forms of media while thinking about this question. There are however, clear differences: for instance, when thinking about the aesthetics of my Omeka platform, I found that I was looking at pages made by students in previous years for inspiration. When I decided to add asterisks to separate my quotes from the rest of my content in this block, I went to Dr. Matthew Huculak for help with html because I do not know how to code. I added the html code for the asterisk shape and the color in the back end of Omeka; however, I could only work within the limitations of Omeka and based on guidance from an expert to build my page. With the necessary skills I could definitely get creative with my Omeka page design, however, making a zine by hand requires no such skill. Expertise has a top-down approach to it and many zinesters, would have a problem with the limitations of online platforms for those with no technical skills.

Despite the limitations of the Omeka remediation of Femzine, there is a possibility that this page could revive the zine by encouraging viewers of the page to seek out the original copy in Special Collections. Additionally, it is important to note that many zinesters are comfortable with putting their zines online: for instance, grrrlzines.net is a website with links to zines from all over the world. The layout of the website is non-linear with images and text interspersed throughout the page. They describe themselves as “The Global Grrrl Zine Network –Grrrl, lady, queer, and trans folk zines, distros and Do-It-Yourself projects from all over the world” (Grrrl zine network). There is definitely a plus to this: a website dedicated to zines can create global networks in ways that the physical medium cannot. There seems to be both positives and negatives to zines having a digital presence as explained by Rosemary Clark-Parsons: “As boundary spaces, digital networks democratize access to zines, while also throwing in sharp relief the democratic failures of the Internet for feminist political engagement (par. 31). Critically engaging with the internet, complete with all its faults, rather than dismissing it entirely in the zine-making world might leave room for the possibility of future online platforms that are more democratic in nature and thus, consistent with the spirit of zines.

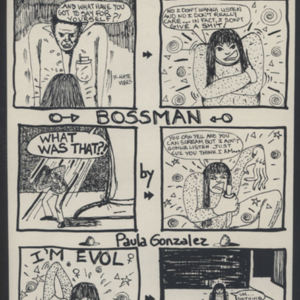

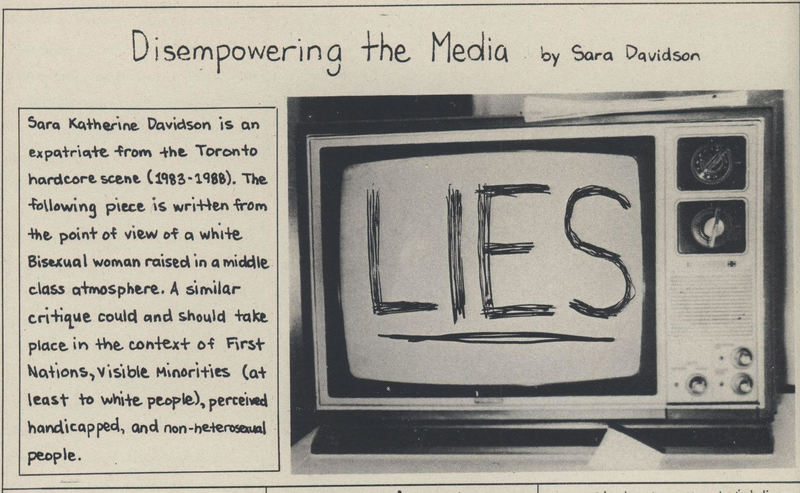

A visual depiction of Sara Davidson's perspective of advertisements on television

An photograph of Corinne and Bee as they discuss their acts of Civil Disobedience. Picture taken by Melanie Aguila.

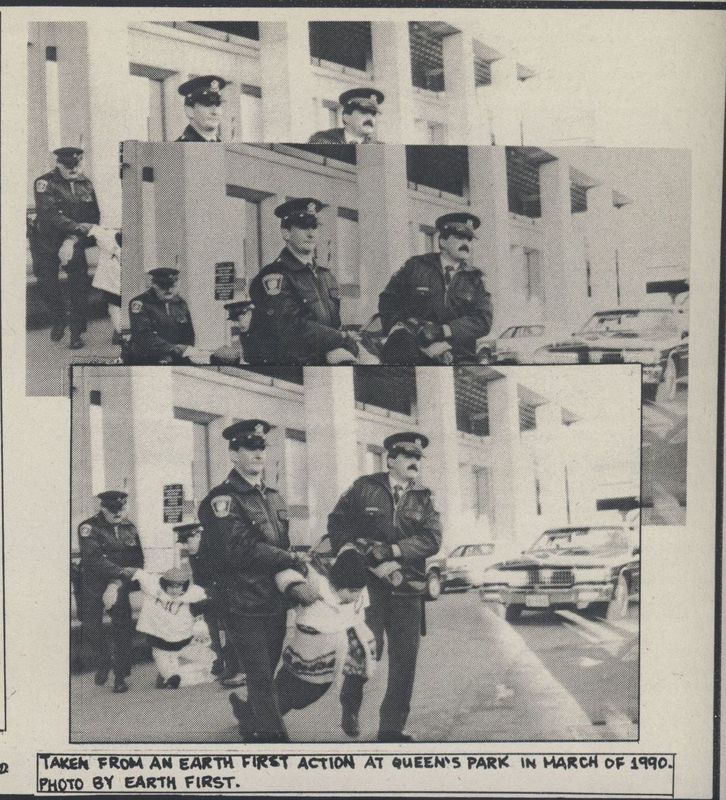

A picture of protesters being round up by police. Taken at Queen's Park.

III. Individual Agency

in Networks of Collective Resistance

Collective resistance against the patriarchy is a strong theme in Femzine. There is a political context to this, particularly in the United States: the elimination of public safety nets in the Reagan era, the emphasis on ideals of rugged individualism fueled by capitalism, and the deregulation of media industries which allowed for increasing commercialization of youth culture by corporate giants like Disney (Chu 76), made many young people turn to zines as an alternative mode of self-expression without buying into mainstream commercialization. When interviewed, many zine publishers also pointed to the accessibility of cheap photocopying and desktop publishing as the reason for the rise of zines that go beyond political, literary and fan interests and are more personal in nature (Chu, 74). Feminist zines in particular came about in 1990s with the rise of the punk movement, often as a response to the sexism that many young women experienced in the punk music scene (Peipmeier, 28).

The editor of Femzine, Melanie Aguila, acknowledges her respect for every artist’s voice in the editorial. She states, “there are different types of feminisms. It is misleading to think that there is only one” (6). She also accepts that while the content of the zine is diverse, it is not meant to represent all women, only those who have contributed to it. To provide more background to the works published in the zine, she had the contributors send her brief write ups about themselves, so that readers can contextualize the pieces they read with the identity, life experiences and beliefs of the creator, to better understand the art. Additionally, she mentions in the editorial that she shared her notes on the interviews with the bands before publishing them, thus giving the interviewees a chance to revise what they have said. In her own words: “By doing this, the interviewer (that’s me!) is put on a more equal level to those being interviewed” (6). Thus, by granting contributors some editorial power before publishing, she respects artists agency over their own work.

Femzine also features an in-depth article on resisting corporate media. Written by Sara Davidson and titled “Disempowering the Media,” the article analyses the problems with advertisements shown in mainstream media (like the television) explaining how “... an item can only be sold if there is a ‘perceived lack’ of something initialized in the potential buyer. Mainstream media ends up not only providing a quagmire of products, it must produce a need for them as well” (10). She deconstructs a yogurt commercial to explain how it reinforces patriarchal notions of gender to sell a product. When she evaluates what the public’s options are for how to deal with the hegemonic structure of corporate advertising, she says, “It is important to scrutinize oneself internally. Though one may be aware of harmful commercials, one must become aware of what endless hammering of extremely racist, homophobic and sexist imagery for years, has done to the ego and to the way one sees other people (11). Additionally, she shares her contact information for readers to reach out in case they need to learn more about how to boycott companies making profits by reinforcing discriminatory stereotypes and find alternatives instead.

Unlike the audience that creators of the above advertisement had envisioned, readers of zines are considered to be agents, not merely passive consumers. This is precisely why some zine publishers do not engage with mainstream media; in an interview with Time magazine, zine publisher Bobby S. Fred said, “Look, this is a nation of disenfranchised kids. The reason we don’t talk to the mainstream media is because we want to guard the few places we have left, like our zines” (qtd. in Chu 77). Fred’s articulation of a zine as a ‘place’ and not an object is interesting; when interviewed by Julie Chu, many publishers voiced the idea of the zine being a place to “build a network” and “form a community” (77). Membership to this network is defined against those who publish in mainstream media networks and established institutions; instead many zine publishers regard themselves as a part of a peripheral network that exists on the margins of society (Chu 78). With this in mind, it is important to consider the location of Femzine in the library. It is located in the Anarchist Archive of the University of Victoria library and situating it thus is very telling of the defiant nature of its content where it forms its own network with other material on subjects like anti-war activism and ecological militancy. While much of this content is ephemeral, the radical nature of it would dissuade mainstream publishers or journalists from engaging with it; the Anarchist Archive allows it room to be and for people to read through and understand these forms of media.

The diversity of the issues addressed in Femzine coupled with the audience they cater to demonstrates how the zine creates a peripheral network for those who are marginalised by society. One example is the exchange between Corrine and Bee titled “Talkin’ Civil Disobedience”. It is a conversation about their acts of civil disobedience and the violence they faced from the police as a result. Through this dialogue they highlight the social inequalities present even in the institutions designed for the protection of minorities. For instance, when Corrine narrates her first act of civil disobedience protesting police brutality against native people, we learn that the Head of Native Affairs, Mike Avansky, was a non-native person. How can a non-native be expected to not only represent, but also act in the best interests of a community that he doesn’t fully understand? Further, we learn through Bee’s participation in the Walk for the Innu of Nitassinan that the Canadian government is using unceded land for military training and even dropping dummy bombs. According to Bee, “The military has stated that no humans inhabit the land, but there are 10,000 Innu in Nitassinan” (31). It is appalling how the military can so easily reduce indigenous people to simply be a part of the environment, just because they live off the land. Sadly, this proves Bobby S. Fred’s point; zines are spaces for not only “disenfranchised kids” but also “disenfranchised adults”, being disempowered by governmental institutions. Even if Femzine doesn’t have a wide reach, it gives these acts of resistance a place to be talked about and shared with individuals who care enough to hear about them, and this is crucial for many who feel marginalised by mainstream society.

IV. In Depth Analysis: Creeps in the Streets

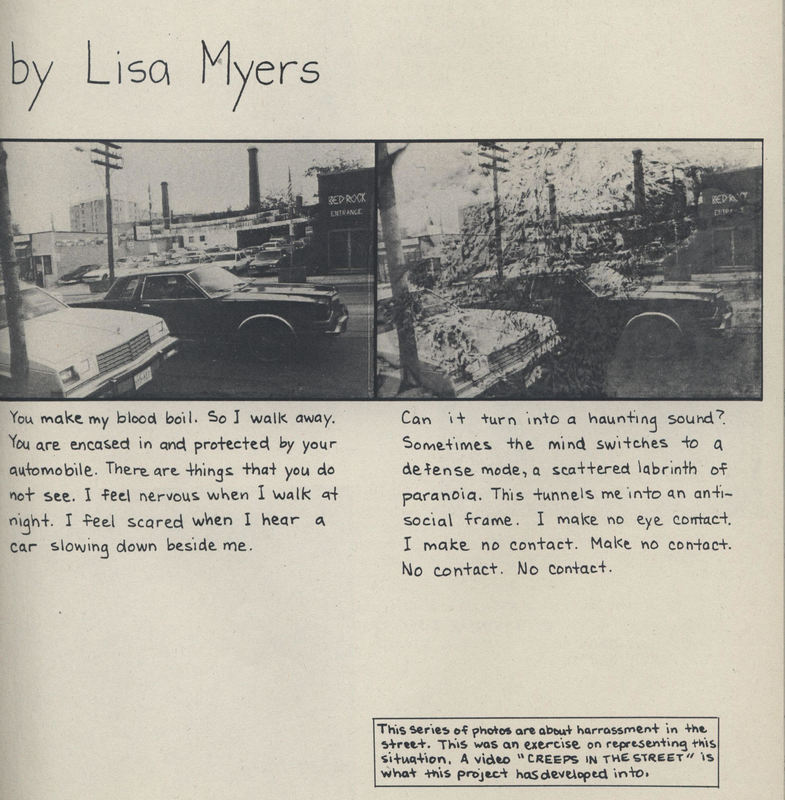

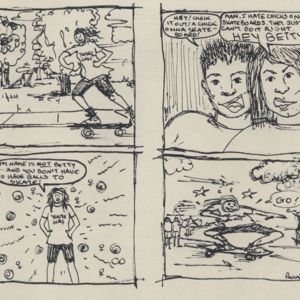

In her piece “Creeps in the Streets” Lisa Myers skillfully navigates the anxieties that women face while moving through public spaces and expresses her frustration at the feeling of powerlessness experienced when sexual harassers aren't held accountable for their actions. The piece features a 4-panel comic accompanied by writing that describes the feeling of being out alone on the street. The work (featured on the left) opens with a panel featuring a car with (as the text goes on to clarify) a woman inside of it. The image of the car here is a metaphor for the woman’s inner strength; the panel establishes that the woman is strong, thus pushing back against the notion of a passive victim of street harassment, and focuses instead on hierarchies of strength and power. The second panel features a second car, one that has crept up behind the woman to harass her. The text here is written in second person and Myers addresses the harasser directly when she says:

“Have you ever been scared as you walked alone at night? I feel you have some insight and information to catch up on.

This is what it actually comes down to:

You are in a car and I am on my feet.

You can drive and I can run.

You can drive faster and I can run.

You can drive fastest and I can scream.

Or you can just

FUCK OFF.” (Myers 22)

The slow build-up of fear in this monologue is worth noting: by adding the comparative “faster” for the speed of the car and not doing the same for the victim, Myers highlights the unequal power dynamic between the perpetrator of harassment and the victim on the streets. It also emphasizes the feeling of being trapped; no matter how fast you run the car will always be faster. In the third comic, she makes this difference explicit as she says,

“You make my blood boil. So I walk away. You are encased in and protected by your automobile. There are things that you do not see. I feel nervous when I walk at night. I feel scared when I hear a car slowing down beside me.”

The fact that she walks away despite the act of catcalling making her blood boil brings up an important aspect of street harassment: the dangers of talking back to the perpetrator for fear of physical or sexual violence. This monologue seems to be meant for victims of harassment as a form of validation and understanding of a shared experience (although to different extents) of something all women go through. This is made evident in the final panel when the author switches out of the second person monologue to a more contemplative tone, where she wonders about the effects of this harassment on her mental health:

“Can it [the sound of the car] turn into a haunting sound? Sometimes the mind switches to a defence mode, a scattered labrinth of paranoia. This tunnels me into an anti-social frame. I make no eye contact. I make no contact. Make no contact. No contact. No contact.”

The image in the panel features a distorted version of the image in panel three, reflecting on the severe consequences on the long-term mental health of women who have to deal with street harassment on a regular basis. The gradual progression from the specific “I make no eye contact” to the generic and repeated “no contact” shows the steady increase in caution employed by the woman as she moves through space; from not making eye contact with the person in the car close to her, it appears that she stops making any contact with anyone at all. Dropping the letter “I” in “Make no contact” has a dramatic effect; it sounds less like her narrating her behaviour outside and more like a command that she is repeating to herself, as a reminder of how she should conduct herself in public spaces.

The act of talking back to a street harasser can have serious repercussions; as recently as July 2018, a woman in France was attacked for confronting her cat-caller on the street. The woman Marie Laguerre, a twenty-two year old engineering student in the city told her aggressor to “Shut Up”. He responded by throwing an ashtray at her upon which she reports, “I burst into rage — the adrenaline rushed through my veins. I insulted him, and I think I said, ‘Are you proud? Son of a bitch’” (qtd. in Caron and Karasz). Upon her saying these words to him, he hit her in public. This incident is telling of the seriousness of street harassment and its effect on women’s well-being. In Marie Laguerre’s words, “Every time a man whistles at me or has this kind of disgusting behavior to me in the street — or even these heavy looks — it makes me angry and then the anger stays” (qtd. in Caron and Karasz). While the #MeToo movement has created a culture more conducive for survivors of sexual harassment and assault it is difficult to make your voice heard through mainstream journalism and many indiviuals may not even want their story to be traceable. Femzine provides a more accessible but also shielded platform to express the suppressed anger that Laguerre is talking about and resist the patriarchy without being pressured to fit a certain narrative of what it means to be victimized.

V. Further Reading

Are you interested in further exploring the University of Victoria's Anarchist Archive? click here.

Are you interested in comics? Click here for a digital exhibit on Chris Ware's The Acme Novelty Library: Final Report to Shareholders and Saturday Afternoon Rainy Day Fun Book (2005)

Are you interested in further exploring digital archives of girl zines? Click here.

Are you interested in how to push back against corporate media? Click here.

VI. Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dr. Alison Chapman for her encouragement and support as I worked on creating this digital exhibit and Dr. Matthew Huculak for lending his technical expertise and making time to explain the inner workings of Omeka.

I would also like to thank the staff members at the University of Victoria’s Special Collections for helping me understand the history of my print object.

Finally, I would like to thank the Fall 2018 English 500/A01 cohort for their thought-provoking suggestions over the course of this term.

VII. Works Cited

Aguila, Melanie and Stephen Perry, editors. Femzine. 1991. Print. University of Victoria Special Collections, call number HQ 1104 F45

Caron, Christina and Palko Karasz. “Parisian Woman Confronted Her Harasser, and Then He Hit Her, She Says.” The New York Times. August 1 2018. Web.

Chu, Julie. "Navigating the Media Environment: How Youth Claim a Place through Zines." Social Justice, vol. 24, no. 3, 1997, pp. 71-85.

Clark-Parsons, Rosemary. “Feminist Ephemera in a Digital World: Theorizing Zines as Networked Feminist Practice.” Communication, Culture & Critique. volume 10, issue 4, 2017.

Dodge, Chris. "pushing the Boundaries - Zines and Libraries." Wilson Library Bulletin, vol. 69, no. 9, 1995, pp. 26-30.

Duncombe, Stephen. Notes from Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture. 2014, Kindle Edition [Microcosm Publisher, 2008]

Gunderloy, Mike. "Zines: Where the Action Is: The Very Small Press in America." Whole Earth Review, 1990, pp. 58-60. ZineWiki. Web. 24 Aug.

Gunderloy, Mike and Cari Goldberg Janice. The World of Zines: A Guide to the Independent Magazine Revolution. Penguin Books, 1992.

Harris, Anita, 1968. Future Girl: Young Women in the Twenty-First Century. Routledge, 2004.

Piepmeier, Alison. Girl Zines: Making Media, Doing Feminism. New York University Press, 2009.

Radway, Janice. "Zines, Half-Lives, and Afterlives: On the Temporalities of Social and Political Change." PMLA, vol. 126, no. 1, 2011, pp. 140-150.

Zobl, Elke. Grrrl Zine Network: Grrrl, lady, queer and trans folk zines, distros and DIY projects from around the world. <http://www.grrrlzines.net>

R.K./Fall 2018