The Dark Blue, and J. Sheridan Le Fanu's "Carmilla" (1871-1872)

I. Introduction

What is the connection between Victorian vampire literature, nineteenth-century serial print culture, and the Pre-Raphaelite movement? Perhaps these topics initially appear to be disparate, but each topic can be connected by the persistent thread of the aesthetic movement in the Victorian periodical The Dark Blue. My Omeka project aims to trace this thread throughout the first two volumes of the periodical, and will culminate with an analysis of the tensions between the birth of the aesthetic movement in the 1860s and '70s and the rise of horror in monster fiction in the nineteenth century.

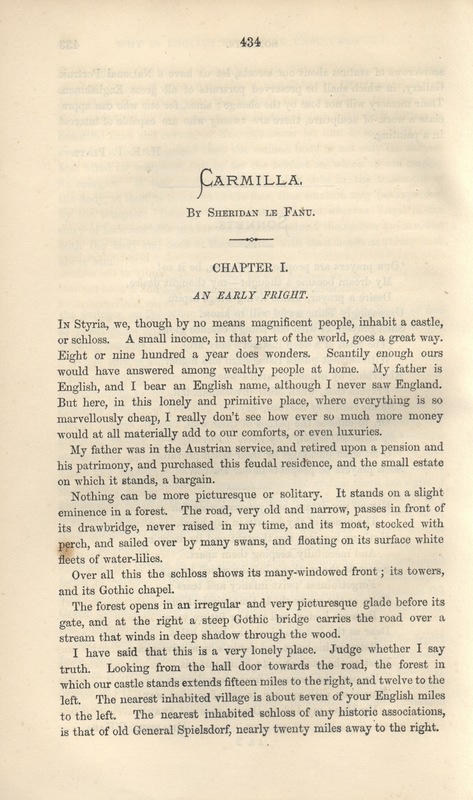

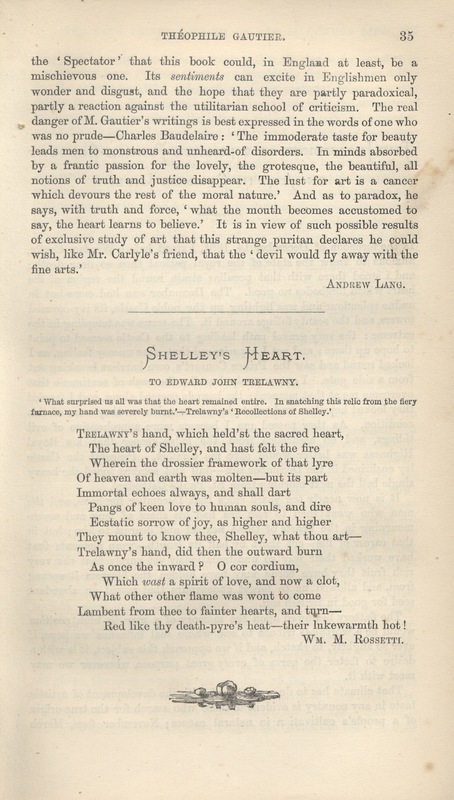

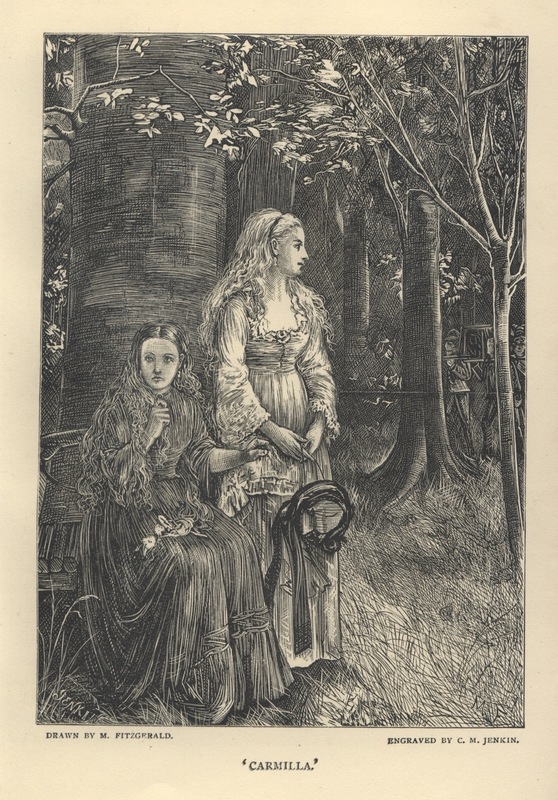

The Dark Blue is perhaps best known to modern audiences for its contribution to vampire fiction; it published J. Sheridan Le Fanu's novella "Carmilla" in four installments from 1871-1872. "Carmilla" features the first significant female vampire of the nineteenth century and the novella contains several narratological horror tropes that have become standard in the vampire genre. Le Fanu's eponymous monster can pass through locked doors, morph into a terrifying and giant black cat, and must be killed via the grisly ritual of staking, decapitation, and fire. "Carmilla" is an important precursor for the most famous of vampire texts—Bram Stoker's Dracula, which was published over two decades later in 1897.

But "Carmilla" is also notable in its overarching themes of feminine desire and lesbianism. Laura, Le Fanu's narrator, dictates her unsettling encounters with the predatory Carmilla, and the relationship between the two women is codified in sexual and romantic terminology. Laura describes Carmilla gazing upon her

with languid and burning eyes, and breathing so fast that her dress rose and fell with the tulmutuous respitation. It was like the ardour of a lover...and with gloating eyes she drew me to her, and her hot lips traveled along my cheek in kisses; and she would whisper, almost in sobs, "You are mine, you shall be mine, you and I are one forever." (594)

Laura is both intrigued and repulsed by Carmilla's obsessive infatuation, and the erotica of "Carmilla" has arguably been the source of the novella's enduring popularity. Since its initial publication as a serial novel, "Carmilla" has spawned numerous adaptions in film, television, graphic novels, and in recent years a highly popular web series.

My project seeks to understand how The Dark Blue and its aesthetic culture influenced the composition of "Carmilla", and especially the three illustrated prints that accompanied the novella. The Dark Blue published on diverse and wide-ranging topics in its brief run, and "Carmilla" is not an exception. Rather, "Carmilla" encompasses a significant network of Victorian artistic culture, and the novella features illustrations that sometimes accompany, and other times actively work against its subject matter. My project argues that these notable divergences in the pictorial elements are evidence of an artistic preference for aesthetic sensibilities over the horrific subject matter.

Content

I. Introduction

II. History of The Dark Blue

i. The Book as a Material Object

III. Victorian Aestheticism

IV. The Pre-Raphaelites

i. Algernon Charles Swinburne and Simeon Solomon

ii. Dante Gabriel Rossetti

V. Illustrated Serials

i. M. Fitzgerald

ii. D.H. Friston

VI. The Aesthetics of the Undead

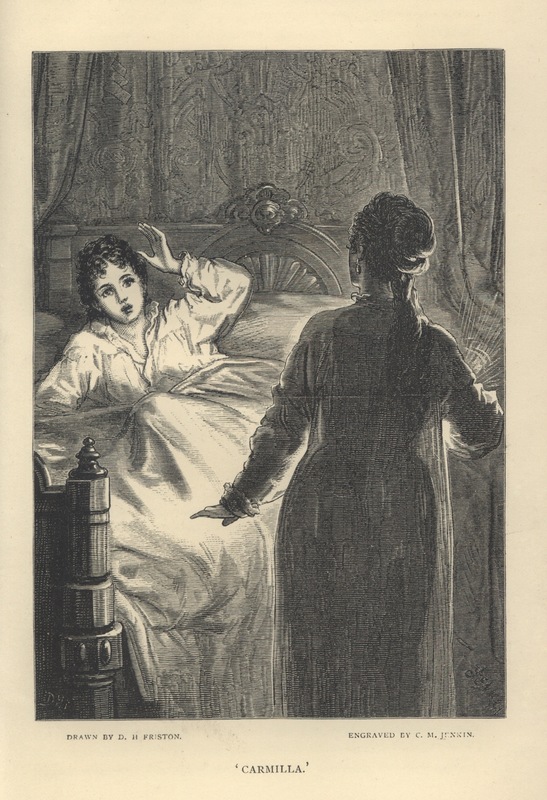

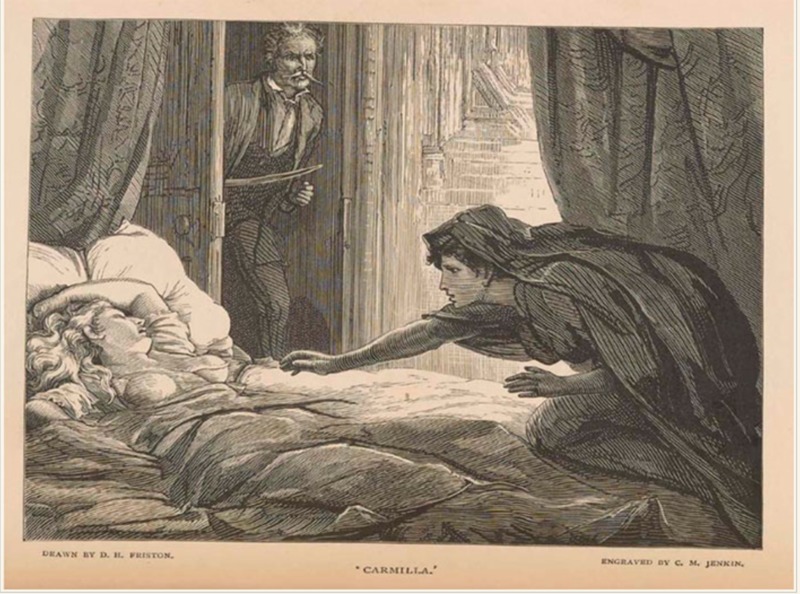

Illustration for the fourth installment of "Carmilla" by D.H. Friston. Friston's image is easily the most popoular of the illustrations for "Carmilla", and continues to be regularly associated with the novella today.

II. History of The Dark Blue

The Dark Blue was first published by John Christian Freund in March of 1871. Named after the colours of Oxford University, the magazine debuted to much fanfare and promise, only to fold in financial disgrace after two years. The Dark Blue is notable for its diverse content, which Anna Maria Jones specifies as a mix of "high art aesthetic and middle brow contributions", of which "Carmilla" certainly belongs to the latter category. The Dark Blue published essays, short stories, translations, and poetry, as well as numerous accompanying illustrations for its featured content.

According to Jones, Freund is not unlike Le Fanu's vampire—alias Mircalla, or Millarca in the novella—and her many names. Jones states that Freund "seems to have invented and reinvented himself throughout his life". Freund was reportedly keen to begin ambitious projects like The Dark Blue, only to later abandon them at the first sign of financial instability.

The Dark Blue debuted with much critical praise and many critics pointed out the potential of the periodical and its myriad content. Early signs of trouble for the magazine were visible almost from the beginning, and Jones argues that Freund tried to financially stabilize the magazine by changing publishers from "established publisher Simon Low to an unknown firm, British and Colonial Publishing Co." in September of 1871 is a clear sign that "all was not well with Dark Blue". Despite these issues, praise for the magazine "continued to be largely positive even in the months immediately preceding its demise" (Jones).

Despite its rather short life in circulation, popularity for The Dark Blue, according to Jones, was warranted for its "impressive roster of early contributors" that included leaders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and other writers "eminent in their day", and "demonstrates the transnational breadth and quality of the journal's content (Jones).

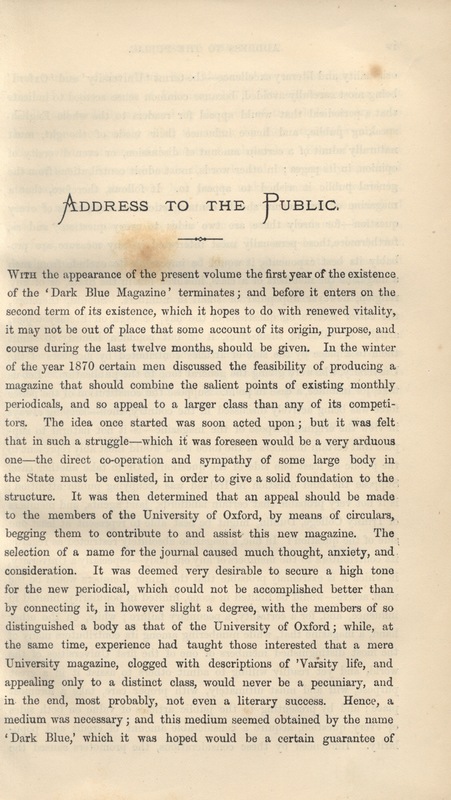

Freund included an address to the public in the second volume, the same volume that debuted Le Fanu's' "Carmilla". In his address, Freund notes that his aim is to "produce a magazine that should combine the salient points of existing monthly periodicals, and so appeal to a larger class than any of its competitors" (iii). Freund mentions the University of Oxford—his alma mater—as a primary contributor for the magazine by being the institution at which many Dark Blue contributors attended, which perhaps hints at the educated audience Freund wished to reach and engage. But Freund also expresses a desire to distinguish The Dark Blue as more than merely "a University magazine" (iii), but as a journal devoted to "originality and literary excellence" (iv). It is of interest to note that Freund uses the dark blue of Oxford's colours as the same colours as the magazine, effectively co-opting the aesthetics of the University.

But what is perhaps most significant about Freund's address is the terminology he uses to describe the magazine. Freund alludes to the magazine's varied subjects, authors, and genres when he calls The Dark Blue "chimerical and absurd" (v). The highly composite identity of the periodical and its far-reaching networks is a foundational component for its role in Victorian aestheticism. Further, Freund states that he hopes to approach the new year, and subsequently a new volume of the magazine, with "renewed vitality" (iii). The idea of "renewed vitality" has some interesting implications with The Dark Blue's early involvement with the genre of vampire fiction. I argue that the influence of aestheticism in the periodical, as well as the reception of an early vampire narrative like "Carmilla", is far from mutually exclusive. Rather, the aesthetic movement and the burgeoning popularity of vampire fiction are intrinsically related.

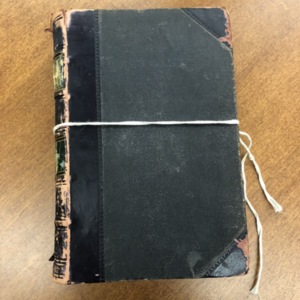

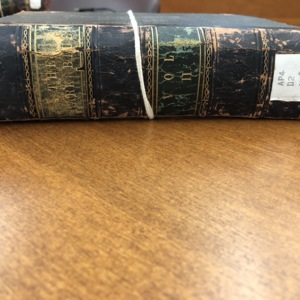

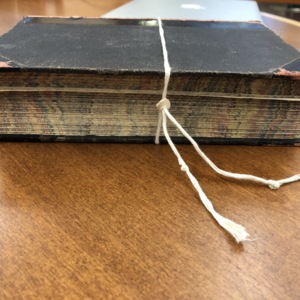

i. The Book as a Material Object

While originally read as a periodical magazine, The Dark Blue was later bound into volumes separated by year. These volumes do not feature any of the original advertisements that would have accompanied the magazine edition, but they do organize the entries in a similar fashion as when they were first published. As a result, "Carmilla" is still presented in three separate installments throughout The Dark Blue's second volume, rather than cohesively placed together, which was typical of collated Victorian periodical volumes.

The volumes that we see here are bound in durable materials, but it is readily apparent that they are falling apart from continuous use. The state of the volumes reflects the enduring legacy of the periodical, as well as its value as a collector's item. The Dark Blue is bound in hard-cover and embossed with gold lettering on the spine between the raised bands, which is also deliberately a dark blue hue to coincide with the periodical title. The volumes also feature a marbled pattern on the fore edge, a clear indication of the publisher's intention of making the collected volume pleasing to the eye.

III. Victorian Aestheticism

There is some scholarly dispute over when the aesthetic movement officially began, though scholars like Jones cite the genesis of aestheticism in the early 1860s and 1870s. The Dark Blue, according to Jones, is "a significant milestone in aestheticism's early development".

Aestheticism as a movement is notoriously difficult to define. In the broadest term, aestheticism is commonly defined as "art for art's sake". Tom Barringer writes that the movement was "[h]ardly a coherent movement... Aestheticism can be thought of as a shared temper of mind that linked creative artists across a range of disciplines from poetry to painting" (161). The aesthetic movement focused on the creation and interpretation of art without reference to the political and social themes of the era. The aim of aesthetic art must - first and foremost - aspire to beauty, be it in the pure form or bodily sensual pleasure. Art should provide refined sensuous enjoyment, rather than convey moral or sentimental messages.

Aesthetic notions of art and beauty are often transcribed as explicitly feminine beauty with an emphasis on sexuality. Elizabeth Prettejohn explains that "[t]he equation of beauty with the erotic image of the female figure might be a regrettable characteristic of a nineteenth-century patriarchal society" (42). Prettejohn uses Dante Gabriel Rossetti's Bocca Baciata as an exemplar of aesthetic art, and that the painting is "an experiment in making a work of art characterized by physical beauty to the exclusion of all other kinds of 'interest', such as an improving moral message" (40). Bocca Baciata has little, if any, narrative inclusion, and the emphasis of the painting is instead focused on the sensual "fleshy" female form. Finished in 1859, Bocca Baciata is very nearly the beginning of the aesthetic painting tradition and "its successors effectively constitute a similar denunciation of the moral responsibilities... in favour of the visual pleasures of art and female beauty in combination" (42).

Aestheticism functions, in a way, as a type of network. Aesthetic theories of art and beauty are often translated across mediums via synaesthetic effects. Synaestheticism, or the stimulation of one sense automatically creating a second sensory experience, is a key component of aesthetic art and the correspondence between art forms such as words, music, and colours.

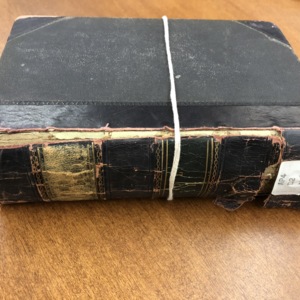

Aesthetic principles are present in The Dark Blue from the beginning in its varied and multitudinous content. The same principles that made John C. Freund dub his magazine "chimerical and absurd" are the same principles that contribute to aestheticism. The Dark Blue features content that is deeply imbued with synaesthetic and translational effects, especially in the contributions from the Pre-Raphaelite circle. I will focus more on the Pre-Raphaelites later, but the first volume of The Dark Blue features a poem titled "Shelley's Heart" by William Michael Rossetti, a prominent member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood as, according to Alison Chapman in her discussion in the Victorian Poetry Network blog, "one of the central forces in aestheticism". Rossetti's poem "plays with the notion of literary associations, as it deploys the trope of the hand - Trelawny's and implicitly the writing hand of Rossetti - to transmit the spirit of Shelley".

One persistent feature of aesthetic art is the way in which artists can transmit the 'spirit' of one art form through another, and this idea applied to literal translations as well. The first volume of The Dark Blue also features the translated story "The Story of Frithiof" by another noted Pre-Raphaelite, William Morris. Translation is perhaps the most literal way in which aesthetes "thought" one art form through another, but the concept of translation goes beyond languages in The Dark Blue and also relates to more pictorial forms of expressions.

IV. The Pre-Raphaelites

The first and second volumes of The Dark Blue contain several contributions by members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. According to Tim Barringer in his book Reading The Pre-Raphaelites, the Brotherhood is "par excellence, the art of mid-Victorian Britain (1848-c. 1875)" (16). The Brotherhood was founded in 1848 and while the Brotherhood itself was associated with many different figures of the era - including painters, poets, critics, and models - the Brotherhood principally consisted of the painters William Holeman Hunt, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and John Everett Millais. The Brotherhood expanded with the inclusion of William Michael Rossetti and others and was eventually associated with other Victorian painters such as Ford Madox Brown and Edward Burne-Jones. The Pre-Raphaelite style is characterized by intense colours, complicated compositions, and a fierce attention to detail and symbolism. Their subjects were often inspired by Italian art before the time of Renaissance painter Raphael, hence the name "Pre-Raphaelite".

Much of the style of the Pre-Raphaelite movement can be seen as a rejection of the then modern method if Victorian painting. According to Tim Barringer, artists - led by Dante Gabriel Rossetti - embraced the rich colours, flat surfaces, and "the simple honesty of fifteenth-century Italian (then known as 'Early Christian') art" (9). "Early Pre-Raphaelitism was above all a literary form of art, closely allied with texts including Shakespeare, Tennyson and the Bible, and often reliant on a further text to explain the pictorial symbolism and detail" (162). Many Pre-Raphaelite paintings include accompanying peices of literature—especially works by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who often wrote poetry for his paintings. In this way, Pre-Raphaelite paintings experimented with how one art form could be translated across mediums, but the Brotherhood is also widely considered to be precursors for the aesthetic movement later in the century for its emphasis on beautiful compositions.

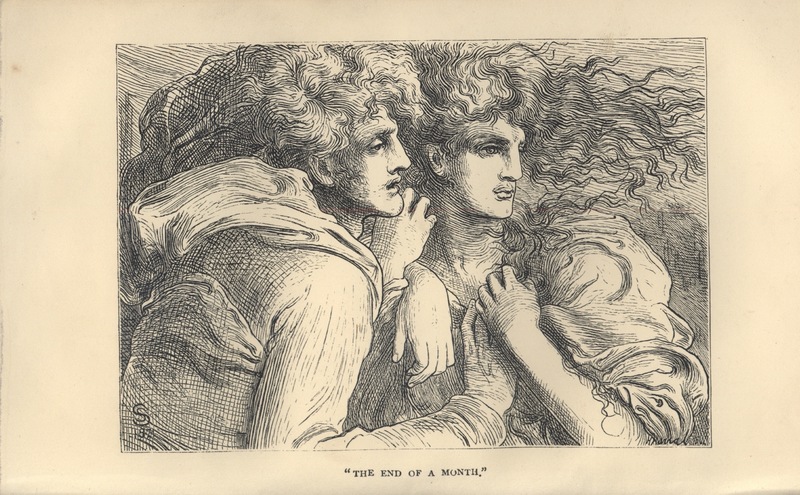

Illustration by Simeon Solomon for Algernon Charles Swinburne's poem "The End of the Month" (1872).

Portrait of Algernon Charles Swinburne by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1861).

i. Algernon Charles Swinburne and Simeon Solomon

The Dark Blue's status as a Pre-Raphaelite publication is intricate and varied, which perhaps reflects the various artistic mediums utilized by the Brotherhood. The Pre-Raphaelites had their own (albeit unsuccessful) periodical that ran briefly in 1850 called The Germ, but they also published their work elsewhere, including in The Dark Blue.

Algernon Charles Swinburne's poem "The End of the Month" was published in the second volume of the magazine and details the afterlife of a scandalous affair. According to Jones, Swinburne's poem blends "descriptions of scent, heat, stickiness, and colour" as a juxtaposition for "the soul's lasting impressions of the lover's passion". The sensual nature of the poem is evident in the accompanying illustration by Simeon Solomon, another artist that orbited the Pre-Raphaelite circle. Solomon is considered an aesthetic artist in his own right, and Jones argues that Solomon captures the turbulent passion of the lovers with their entwined wrists and the "intermingled locks of hair", symbolizing the interconnections of the couple that will soon be severed. Solomon's androgynous figures are a recognizable aspect of his style, which Jones hints at as "a connection between aesthetic innovation and same-sex eroticism". It is interesting to compare the arguably homoerotic images of Solomon with the illustrative interpretations of D.H. Friston for "Carmilla", which will be discussed at length in the next section, specifically because the illustrations for "Carmilla" are not, by any stretch of interpretation, androgynous. Rather, the novella's illustrations make the gender and sexuality of their subjects readily apparent for the reader, which has interesting implications for aestheticism and its obsession with female beauty. The beauty of women, and especially the seduction of women, is a persistent theme that runs through much of the Pre-Raphaelite contributions to The Dark Blue.

Illustration by Ford Madox Brown for the poem "Down-Steam" by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1872).

Final illustration by Ford Madox Brown for the poem "Down-Steam" by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1872).

ii. Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, arguably the most pre-eminent of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and its pseudo-founder, published his poem "Down-Stream" in October of 1871. The poem includes two accompanying illustrations by another Pre-Raphaelite artist, Ford Madox Brown. Rossetti's poem details the love affair between a man and a woman, the woman's subsequent abandonment, illegitimate pregnancy, and ends with the woman drowning herself in the same river by which she and the man had an affair. Madox Ford's illustrations detail first the seduction in the boat, or punt as it is called in the poem, and then illustrates the bleak nature of the poem's closing lines in the final image. Depressing as the subject matter is, seduction and abandonment were popular topics for art and literature in the Victorian era. But further, the subject matter of "Down-Stream" has some interesting implications with the aesthetic movement. The poem revolves around a tale of a woman being taken advantage of, and the intrinsic connections made between the text and the image, as well as death and sexuality, are readily apparent, and "Down-Stream" is not an anomaly in terms of its subject matter.

Considering death and sexuality, it is perhaps a natural progression toward a discussion of the Victorian vampire. The Pre-Raphaelites and their obsession with the beautiful, sensual female form can arguably be viewed as parasitic in nature, especially considering the Pre-Raphaelite's and their rather torrid history with their model subjects. Christina Rossetti—sister to Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Michael Rossetti, as well as an established poet in her own right—composed her poem "In The Artists Studio" in 1856, inspired by her brother's portraits of his wife, Elizabeth Siddal. In the sonnet, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, as the artist, "feeds upon" the face of his beautiful model "by day and night...not as she is, but as she fills his dream" (9-14). Alison Chapman points out in her blog for the Victorian Poetry Network that the relationship between male artist and female muse is one of "vampiric consumption" in Rossetti's sonnet, and that this inherently parasitic relationship is "dependent on [the artist's] artistic fantasies". Rossetti's wife—who by some accounts commited suicide in 1862—was also a muse for many of Rossetti's other paintings, though Rossetti appears to become even more parasitic with Siddal in immortalizing her death in Beata Beatrix.

Beata Beatrix is modelled after Elizabeth Siddal, though it was completed in 1864, a few years after her death. Rossetti quite literally draws a clear parallel between the mythic relationship between the Medeival poet Dante and Dante's love, Beatrice. Like Beatrice, Elizabeth Siddal died young, and Rossetti paints his wife in a death-like trance, where she is neither quite alive nor quite dead. Barringer argues that Beata Beatrix implies "a connection between the vision of death and the state of sexual ecstacy" (158). Rossetti paints his wife in a vampiric state, but the boundaries between artist and muse, vampire and victim become blurred once we approach "Carmilla", and becomes especially complicated because the novella involves two women, with one distinctly feeding off of the other in a parasitic relationship that is codefied as erotic. While the character of Carmilla has noticibly assertive, and therefore masculine traits, these traits are curiously absent in the novella's illustrations, which instead amplify Carmilla's sexual form.

V. The Illustrators: M. Fitzgerald and D.H. Friston

i. M. Fitzgerald

Illustration played a key role in serialized narratives in the nineteenth century, though many of the illustrations no longer accompany the text once it is published a novelized format. According to Mary Elizabeth Leighton and Lisa Surridge, one "cannot simply conflate the serial and volume editions of illustrated Victorian novels and analyze them as the same text" (65). Novellas like "Carmilla" were available to the reading public first in serial installments, and the accompanying illustrations are "intrinsic to the first reading experience of the mass Victorian public" (66). Leighton and Surridge examine illustrations in realist and sensationalist fiction from the 1850s and '60s, and Le Fanu's "Carmilla" actively participates in this illustrated tradition.

Carmilla features accompanying illustrations for three of its four serial installments; one by Michael Fitzgerald and two by David Henry Friston. M. Fitzgerald, as he will henceforth be called, appears to have worked, according to Simon Houfe, primarily with "Irish peasant subjects and middle class subjects" (137). Fitzgerald was apparantly admired by Vincent Van Gogh for his illustrations, which make "Carmilla" and its sensationalist subject matter rather off-brand for Fitzgerald.

But the illustrations in "Carmilla" are significant in their noted divergence from the source material. There is an established pattern in the illustrations of altering, and especially downgrading the more unsettling narrative aspects of Sheridan Le Fanu's Gothic tale. Fitzgerald's illustration features the scene in "Carmilla" where the vampire and Laura are witnessing a funeral procession for a young girl that has mysteriously died in the nearby village—most likely murdered by the parasitic Carmilla.

Fitzgerald shows the two women having different reactions to the funeral music. Jones points out that "Laura stands to show respect for the mourners and join them in their hymn-singing, and Carmilla reacts with disgust and anger". Fitzgerald's image appears to illustrate the moment where "Carmilla struggles to suppress her reaction to the music".

She sat down. Her face underwent a change that alarmed and even terrified me for a moment. It darkened, and became horribly livid; her teeth and hands were clenched, and she frowned and compressed her lips... All her energies seemed strained to suppress a fit, with which she was breathlessly tugging; and at length a low conculvise cry of suffering broke from her." (Le Fanu, 596)

Jones argues that Fitzgerald "offers stillness that is really physical and emotional turmoil", but it is difficult to substantiate such a clear deviation from Le Fanu's text. Far from the "horribly livid" face and clenched "teeth and hands", Carmilla's face appears haughty instead of terrifying in its anger. Further, Fitzgerald does not convey Laura's feelings of discomfort towards her companion and instead has Laura gazing demurely towards the procession. While Le Fanu has Carmilla bid Laura to "sit down here, beside me; sit close; hold my hand; press it hard - hard - harder" (596), Fitzgerald emphasizes the distance between the two women by keeping Laura standing. While Carmilla's possessive attitude towards Laura is hinted with the vampire's hand clenched in the folds of Laura's dress, the two women are pointedly not touching. This obvious downplaying perhaps has more to do with creating a balanced composition, and the pattern of diluting the story's horror elements continues in the illustrations of D.H. Friston.

D.H. Friston's illustration for the fourth installment of J. Sheridan Le Fanu's "Carmilla" (1872).

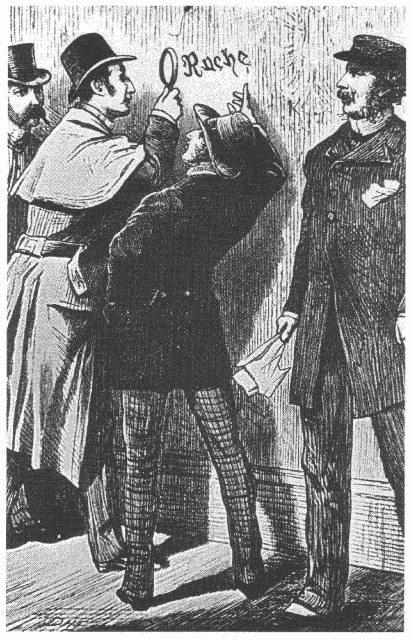

D.H Friston's illustration for Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes tale A Study in Scarlet. This illustration is nearly the first ever illustration of Sherlock Holmes.

ii. D.H. Friston

D.H. Friston is a significant artist in the late Victorian period, and he was one of the first illustrators for Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes stories in 1887. But before that, Friston was a prolific figure painter and illustrator for serial fiction who, according to Houfe, specialized in "theatrical scenes and portraits in black and white" (144).

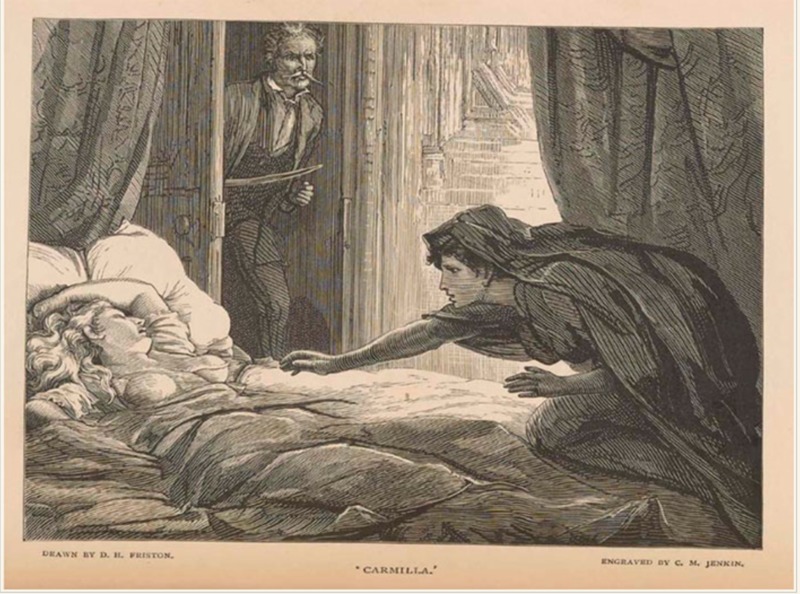

Friston's illustration for the fourth installment for Carmilla—and arguably the most famous image associated with the novella—also features some interesting divergence from the source material. The text—through the embedded narrative of General Spielsdorf—describes Carmilla as "a large black object, very ill-defined" which "swiftly spread itself up to the poor girl's throat, where it swelled, in a moment, into a great, palpitating mass" (74). Friston uses light and shading to communicate the sinister nature of the scene. The dark figure of Carmilla is shown crawling over the bed of her sleeping victim. Friston emphasizes the passivity of Carmilla's victim by drawing her arms draped dramatically over her head, leaving her body completely exposed to Carmilla—but also our gaze. Friston minutely illustrates the curves of the female form for both of the women, but especially the helpless Bertha.

Jones articulates the "voyeuristic dynamic" of Friston's image by pointing out how the illustration "plays up the eroticism of the scene and minimizes the horror". According to Jones, Carmilla is far from the "palpitating mass" of Le Fanu's source material and is instead depicted as "an attractive, if sinister woman". These notable divergences offer a direct correlation to the illustrations of sensation fiction one decade prior. Friston's illustrations for "Carmilla" enact the tropes of sensation genre, including "characters in motion, boundary crossing or liminal spaces, female transgression or nocturnal activity, moving fabric, and the use of white space to create ghostly effects" (Leighton and Surridge, 71). Leighton and Surridge argue that transgressions from the source material in sensationalist fiction—a genre to which "Carmilla" arguably belongs—tended to be "symbolic and indirect, focusing not so much on illustrating major events... as in creating a sense of instability, transgression, and turbulence" (70).

But Le Fanu's source material is arguably already transgressive. The horror aspects of the text, where Carmilla is an inhuman, indistinct black form, is already an unstable image to convey. So why then, do the illustrators for "Carmilla" take such licence with the source material, and favour images that focus on the sensual female form? It is not irrational to argue that "Carmilla" and its illustrations are influenced by the burgeoning aesthetic movement that virtually surrounds the magazine, and this statement is especially true when analyzing D.H. Friston's other illustration for the novella.

VI. "Renewed Vitality": Or, the Aesthetics of the Undead

Le Fanu's "Carmilla" also contains several translational aspects that are so intrinsic to the aesthetic movement in terms of its formatting. Laura's tale is presented as part of a case study for Le Fanu's fictional occult detective Dr. Hasselius, and Laura begins her story already explaining, and perhaps apologizing, it to be a type of translation. Laura speaks several languages and has ostensibly translated her tale, and Jones argues that the "shifts between languages and their relationship to the subjects who speak and inhabit them" is the "central problem" of the text. But further, Carmilla, with her myriad of names, invents and "translates" herself from one generation to the next, which certainly complicates matters for the novella.

But the translation of the novel also affects, according to Jones, a "shifting of sensory and emotional impressions from one register to another". In "Carmilla", and even other popular works of the Victorian Gothic, "monstrous predation overlays sexual desire, pleasure commingles with pain" (Jones). Interestingly, the accompanying illustrations for Carmilla—and especially the two illustrations composed by D.H. Friston— appear to exclude the "monstrous predation" of the novella, and instead focus on the sensual, aesthetic aspects.

It comes as no surprise that the illustrations for "Carmilla" enact the aesthetic principles that are so prevalent throughout The Dark Blue and the networks that encompass the magazine. Carmilla may be an indistinct black shadow without a corporeal body, or a supernatural creature covered in blood in Le Fanu's source material, but she was clearly presented to Victorian readers first as a beautiful woman. "Carmilla" and its illustrations effectively embody the obvious tensions between two polar opposites: the aesthetic movement and the birth of the horror genre.

If aestheticism is devoted to beauty and sensual pleasure, the horror genre is perhaps meant to unsettle and to displease. Stephen T. Asma explores the relationship between monsters and horror in his book On Monsters, and defines horror in its Latin term "horrere", or to "stand on end" (152). The defining aspect of the horror genre is to put the reader, or perhaps viewer in terms of horror and cinematic film, on an uncomfortable edge. But horror is also the ineffable emotion that one fears when one is afraid of something unfamiliar" (152). Carmilla, as a vampire, is definitely unfamiliar to Le Fanu's narrator, and thus Carmilla is as fascinating as she is repulsive to Laura. Carmilla is "strange and beautiful" to her victim, and the vampire's advances are both "hateful and overpowering" (Le Fanu, 594).

"I saw Carmilla, standing, near the foot of my bed, in her white night-dress, bathed, from her chin to her feet, in one great stain of blood" (Le Fanu, 704).

Friston's second illustration for "Carmilla" depicts the pivotal scene in which Laura dreams she is being attacked, only to awaken suddenly to see Carmilla standing over her "bathed, from her chin to her feet, in one great stain of blood" (704). The scene is arguably one of the most 'vampiric' scenes in the novella, and certainly the first clear instance of Carmilla's monstrosity. Yet Friston's illustration is completely devoid of the monstrous aspects of the scene. He depicts Laura "seeing but not yet really seeing Carmilla for what she is" (Jones). Friston positions the scene so that we as readers do not see Carmilla covered in blood, but rather "the appealing innocence and vulnerability of her victim" (Jones). Jones argues that Friston's illustration blurs the boundaries between the reader and the vampire by focusing our perspective "somewhere between the narrator's [Laura's] experience and the vampire's point of view, viewing Laura from the foot of the bed even as the narrative describes the same scene from the reverse angle".

But it is the sensual nature of Friston's image that marks a significant alteration from the source material. Jones notes that Friston obviously showcases Carmilla's "sex appeal" with the "outline of her naked curves visible through her sheer backlit gown". But further than this, Carmilla is very obviously feminine. Friston pays particular attention to her elaborate, cascading hairstyle, her dangling earring, and a glimpse of long eyelashes. Far from being undead, Carmilla is sensuously, and therefore vitally, alive through a depiction of a body that readers cannot possibly ignore. Friston's illustrations palpably enact the aesthetic devotion to the sensual female form, thereby reversing the parasitic formula of the vampire. We, as aesthetic readers, are the ones feeding off of the images of the beautiful female form, and the principles of this inversion go beyond mere voyeurism, but are subject to larger forces concerning the beauty of art, the horror genre, and how we as readers can often be caught somewhere in between the two.

S.K./Fall2018

Works Cited

Asma, Stephen T. On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears, Oxford University

Press USA - OSO, 2009

Barringer, T. J. Reading the Pre-Raphaelites. Yale University Press, New Haven, 2012.

Chapman, Alison. “Poem of the Month: Christina Rossetti's ‘In the Artist's Studio.’” Oct. 2011.

n. pag.Victorian Poetry Network. [Web. 25 Nov. 2018].

---. “Poem of the Month: William Michael Rossetti’s ‘Shelley’s Heart.’” 8 Mar. 2012.

n. pag.Victorian Poetry Network. [Web. 25 Nov. 2018].

Freund, John Christian. "Address to the Public". The Dark Blue. Vol. II. i-v, 1871.

Houfe, Simon, 1942. The Dictionary of 19th Century British Book Illustrators and

Caricaturists. Antique Collectors' Club, Woodbridge, Suffolk, 1996.

Jones, Anna Maria. “On the Publication of Dark Blue, 1871-73.” BRANCH: Britain,

Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga.

Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. [Web. 7 Nov. 2018].

Le Fanu, Sheridan J. Carmilla. Prime Classics Library, 2005.

---. "Carmilla." The Dark Blue. Vol II. September to February. pp.434-48, pp.592-606, pp.701-14. 1871-72.

Leighton, Mary Elizabeth, and Lisa Surridge. “The Plot Thickens: Toward a Narratological Analysis

of Illustrated Serial Fiction in the 1860s.” Victorian Studies, vol. 51, no. 1, 2008, pp. 65–101.

Prettejohn, Elizabeth. Art for Art's Sake: Aestheticism in Victorian Painting. Yale University Press

for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2007. Print.

Rossetti, Christina G., 1830-1894, R. W. 1. Crump, and Dinah Roe 1976. Christina

Rossetti: Selected Poems. Penguin Books, London;New York;, 2008.