The Girl's Own Paper: Supplementary Volume [1915]

Contents

I. Introduction and Methods

II. The Girl’s Own Paper and The Girl’s Own Annual: History and Context

III. The Front Free-endpaper and the Story of Ownership

IV. Printing and the Story of Production

V. Further Reading

VI. Acknowledgments

VII. Works Cited

I. Introduction and Methods

“Not only do objects change through their existence, but they often have the capability of accumulating histories, so that the present significance of an object derives from the persons and events to which it is connected.” (Gosden and Marshall 170)

✧✧✧

This Omeka page explores The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume—a unique bound volume of a popular British periodical for adolescent girls. Following Karin Dannehl, Chris Gosden, and Yvonne Marshall’s work in material studies, my methods for textual analysis combine book history, object biography, and life cycle studies. I begin from the position that the book as a material object does not only contain written stories but is a story in and unto itself; its material aspects constitute elements of an overarching and socially-constructed narrative. A central tenet of object biographical studies is that an object’s life story is informed by its unique histories of production, circulation, and use; that said, Karin Dannehl suggests that one should also attend to what is common or “generic” about an object—i.e. its life cycle (124). Thus, I frame this book’s biography concurrently around what makes it exceptional or singular and what makes it a common, everyday object, particularly in relation to its historical and generic contexts. These analytical methods are indebted to Sergei Tretyakov’s influential essay, “The Biography of the Object” (1929) which, although concerned with the written worlds of narrative texts, was among the first critical inquiries into the social and relational meanings that become embedded in common objects.

This Omeka page remediates parts of The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume in order to illuminate key constitutive elements of its particular biography and its generic life cycle (Dannehl 133; emphasis added). Drawing on work in book history and object studies, I demonstrate how, by contextualizing these digitized parts, this humble volume of adolescents’ periodicals can be read historically and materially through a conceptual framework of memory, nostalgia, and loss. Through this work, this page becomes a case study for demonstrating how analytical methods grounded in new textual studies can reveal concealed meanings within books that cannot be gleaned from text alone.

This page simultaneously works within the tradition of Andrew Stauffer’s NINES-sponsored project, Book Traces. Book Traces is a “crowd-sourced web project” that archives photographs of marginalia found within circulating nineteenth-century library books in order to “engage the question of the future of the print record in the wake of wide-scale digitization.” In other words, Stauffer and his research team are emphatically foregrounding materiality in the remediation of pre-digital books. Technically, The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume’s inclusion in Special Collections excludes it from the current scope of the Book Traces project; nonetheless, this Omeka page emulates the project’s central aims through its self-conscious positioning of material studies in relation to processes of digitization and remediation. Where Book Traces is concerned with archiving traces of ownership and histories of use in distributed collections, this Omeka page takes the opposite approach and conducts an object-focused critical inquiry into the story of one specific book.

In the sections that follow I begin by providing historical context for The Girl’s Own Paper and the accompanying Girl’s Own Annual in order to elucidate the culturally and historically contingent meanings accumulated by this supplementary volume. Next, I explore the book’s story of ownership and histories of use, focusing on handwritten inscriptions in the book’s front-matter. Moving on from what makes this book exceptional or singular, I apply the same methods and framework to its generalities in print production and its mise-en-page (i.e. layout). Throughout these sections, I attend to how the pages of this book contribute to my project’s conceptual frame of memory, nostalgia, and loss. The final sections of this Omeka page include suggestions for further reading, acknowledgements, and a Works Cited list.

Key terms and concepts: object biography; life cycle studies; story; remediation; digitization.

Fig. 1: Original masthead for The Girl's Own Paper, volumes 1–16 (1880–1895).

![Front Cover of <em>The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume</em> [1915] Front Cover of <em>The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume</em> [1915]](../../../../files/thumbnails/b045662b688abb96bc0c02e3adcbfd8a.jpg)

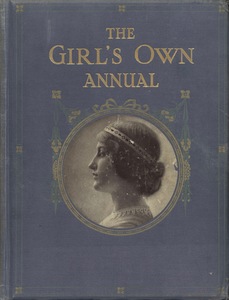

Fig. 2: Front cover of The Girls' Own Paper: Supplementary Volume [1915].

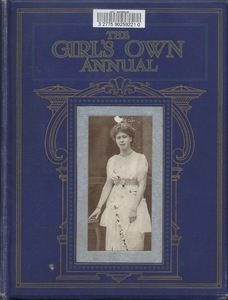

Fig. 3: Front cover of The Girl's Own Annual (1915).

II. The Girl’s Own Paper and The Girl’s Own Annual: History and Context

The Girl’s Own Paper was an illustrated periodical for adolescent girls published by London’s Religious Tract Society and distributed by the Leisure Hour Office between 1880 and 1956. It was released weekly at the price of one penny and was marketed to Britain’s lower-middle-class girls as a suitable moral alternative to the ever-popular penny dreadfuls (Doughty 7). Nevertheless, as Sally Mitchell writes in The New Girl: Girls’ Culture in England 1880–1915, The Girl’s Own Paper’s reader-generated correspondence and autobiographical sections reveal that it actually reached a cross-class readership that included servants as well as girls from the professional classes (27). This cross-class appeal made The Girl's Own Paper “the first broadly successful magazine for girls” (Mitchell 27). To girls of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, an object bearing the name The Girl’s Own Paper could be immediately recognized as popular, ubiquitous, and familiar.

Throughout its long run of publications, The Girl’s Own Paper primarily featured educational articles, short fiction, and instructional texts on cooking, sewing, etiquette, and household management. The weekly issues also reached out to their readers by including contests and correspondence sections. This tactic invited readers to see themselves as contributors and thus prompted them to develop personal relationships with the periodical. In turn, these editorial gestures contributed to the books’ accumulation of socio-cultural and relational meanings. The contributions to The Girl’s Own Paper were typically conservative in nature. For example, the 1911 Extra Christmas Part in this supplementary volume contains an editorial decrying “The Girl In the Skimpy Skirt”; the general editor writes, “We have seen a very great deal of her—far too much of her, in fact” (Girl’s Own Paper 32). That said, scholarship tends to highlight the periodical’s ambivalence rather than its outright resistance to the era’s shifting understanding of gender roles. Scholars such as Sally Mitchell, Kristine Moruzi, Cynthia Allen Paton, and Beth Rodgers contend that The Girl's Own Paper constructs the cultural idea of “girlhood” by way of internal contradictions. The periodical juxtaposes conservative rhetoric surrounding girls’ modesty, deference, and decorum with articles and advice columns that encourage community, professionalization, physical fitness, and an overall spirit of independence. The latter rhetoric was especially important at the end of the long nineteenth century when women were gaining increased access to higher education and were beginning to leave their traditional roles as servants and housekeepers in favour of professional employment in the public sphere. Sally Mitchell thus positions the “New Girl” constructed by The Girl’s Own Paper and the popular periodical press within “a provisional free space” (3) wherein girls’ agency could be gradually cultivated by way of an internal dialectic between deference and independence.

Mitchell, however, is careful to note that this “provisional free space” was an interpretative possibility and not a guaranteed instigator of social change (3). It is impossible to know the extent to which this rhetoric was recognized or internalized by its readers. And, in any case, small degrees of progress can hardly make amends for the sheer ubiquity of conservative gender policing in adolescent girls’ periodicals. With that said, this historical and cultural context is all pertinent to The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume’s biography. This context precedes the reader’s initial encounter with the object and imbues the first encounter with cultural meaning. To the late-nineteenth and early twentieth-century reader, The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume would have already been considered common, familial, and personal simply by virtue of its title, generic history, and its socio-economic status.

The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume also actively participates in a context of gift-giving and social exchange. In “The Cultural Biography of Objects,” Gosden and Marshall remind us that “objects are understood to accumulate histories as they repeatedly move between people” (174; emphasis added). As previously stated, after its initial publication in 1880, The Girl’s Own Paper quickly became “the most popular girl's magazine of the century” (Moruzi 83). Following the precedent of its companion magazine, The Boy’s Own Paper (1879–1976), the Religious Tract Society capitalized on the periodical’s successes by releasing The Girl’s Own Annual at the end of every calendar year. With the exception of the first annual, these books contained the year’s issues from October to September and were intended to be bought and sold as Christmas gift books (Doughty 6). This additional context heightens the religiosity of the periodical; and, it also brings the question of ownership to the forefront of object biographical inquiry. For, in Gosden and Marshall’s words, “gifts always maintain some link to the person or people who first made them and the people who have subsequently transacted them” (173).

With all this being said, it is important to note that The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume is neither a weekly issue of The Girl’s Own Paper nor a bound copy of The Girl’s Own Annual. A third stylistic option was available to the Girl’s Own Paper enthusiast of the early twentieth century. Instead of buying a bound annual, readers could choose to have selected issues bound privately “using specially printed boards obtained from the Girl’s Own Paper Office” (Ward). The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume from the University of Victoria’s Special Collections was both privately compiled and privately bound. Thus, this book is singular. It includes four extra Christmas parts that were originally published in 1911, 1912, 1914, and 1915. None of the issue title pages appear within the volume, either because they were removed post-printing or because they were omitted from the printing process.

Although it is not a complete Christmas annual, this supplementary volume emphatically positions itself within a Victorian tradition of Christmas books and gift-giving. Moreover, its singularity and the fact that it was privately-printed emphasizes the importance of social exchange and ownership relations to its object biography. Although this volume is composed entirely of extra Christmas parts from the 1910s, the aesthetics of the volume’s front cover hearken back to early to mid-nineteenth century gift book aesthetics. In particular, the red cloth and gold lettering on the cover is a nostalgic nod to the popular early and mid-Victorian Christmas annual, The Keepsake (pictured on The Victorian Web). And so, by virtue of its socio-historical contexts, The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume accumulates biographical contexts that are equally premised on nostalgia for a bygone era and the faded memory of personalized social transactions.

“If gifts maintain an unbreakable attachment to the people who made and transacted them in the past, then all gifts are multiply authored: that is, they are produced by a range of different people and a plethora of links.” (Gosden and Marshall 173)

✧✧✧

![Front Free-Endpaper of <em>The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume</em> [1915] Front Free-Endpaper of <em>The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume</em> [1915]](../../../../files/fullsize/d1ca75c8832e15814c25de3b7e420779.jpg)

Fig. 4: Ownership inscription “To Lorna / daughter of Grace. / June 1968” on the front free-endpaper of The Girl's Own Paper: Supplementary Volume [1915].

![Front Free-Endpaper of <em>The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume</em> [1915] Front Free-Endpaper of <em>The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume</em> [1915]](../../../../files/fullsize/cfb2a2773e2ec1cda8fe41ac1d0b24be.jpg)

Fig. 5: Ownership inscription “To Grace, / with much love / from her devoted sister / Pattie.” on the front free-endpaper of The Girl's Own Paper: Supplementary Volume [1915].

![Front Free-Endpaper of <em>The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume</em> [1915] Front Free-Endpaper of <em>The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume</em> [1915]](../../../../files/fullsize/3ca9269fdcce5385823443e8964857e1.jpg)

Fig. 6: Inscription “Christmas / 1918” on the front free-endpaper of The Girl's Own Paper: Supplementary Volume [1915].

![Front Free-Endpaper of <em>The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume</em> [1915] Front Free-Endpaper of <em>The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume</em> [1915]](../../../../files/fullsize/8ff5098a02b1893a3bb6adf8c8b50c88.jpg)

Fig. 7: Mourning quotation on the front free-endpaper of The Girl's Own Paper: Supplementary Volume [1915].

![Front Free-Endpaper of <em>The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume</em> [1915] Front Free-Endpaper of <em>The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume</em> [1915]](../../../../files/fullsize/5e6c7e4c9aa3ed300901ce394c7fea39.jpg)

Fig. 8: Excerpt from Oliver Goldsmith’s “Elegy on the Death of a Mad Dog” on the front free-endpaper of The Girl's Own Paper: Supplementary Volume [1915].

![Front Free-Endpaper of <em>The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume</em> [1915] Front Free-Endpaper of <em>The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume</em> [1915]](../../../../files/fullsize/2519b66ca46dea377705ffdae2066cd9.jpg)

Fig. 9: Excerpt from Walter Scott’s “The Lady of the Lake” on the front free-endpaper of The Girl's Own Paper: Supplementary Volume [1915].

![Population [Sixth Census of Canada, 1921] : British Columbia, District No. 19, Sub-District No. 20 in North Saanich Population [Sixth Census of Canada, 1921] : British Columbia, District No. 19, Sub-District No. 20 in North Saanich](../../../../files/fullsize/0bf2ec02bb21db4ae49222d928c5ca98.jpg)

Fig. 10: The Simister family in the Canadian Census of 1921.

III. The Front Free-endpaper and the Story of Ownership

The front free-endpaper, the blank page that separates the book’s cover from the text block, is undoubtedly the most pertinent piece of paper in this object’s biography. This paper contains inscriptions written in two varieties of ink and by at least two and possibly three different hands. At the top of the front free-endpaper, three specific inscriptions elucidate the book’s provenance (i.e. its origins and its history of ownership) and its particular context of social exchange. First, in the upper-left corner of the page, the handwritten words “To Lorna / daughter of Grace. / June 1968” appear in blue ballpoint ink. Next, approximately two and a half centimeters below this first inscription, the handwritten words “To grace, / with much love / from her devoted sister / Pattie” appear either in brown ink or in ink that discoloured to brown over time. Finally, the handwritten words “Christmas / 1918” appear in a hand and ink colour that matches Pattie’s in the upper-right corner of the paper. And so, from the front free-endpaper, one can immediately glean that a person named Pattie gave The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume to her sister Grace for Christmas in 1918 and that Grace passed it on to her daughter Lorna fifty years later.

Working from Special Collections’ donor records, I ascertained that this book was donated to the University of Victoria’s Special Collections in 2008 by Dr. Edward B. Harvey and the Honourable Dr. Lorna Marsden (Dean). Dr. Lorna Marsden, “daughter of Grace,” is an eminent Canadian sociologist and former politician who grew up in Sidney, British Columbia, slightly North of the University of Victoria (Sleeman 364). Dr. Marsden attended Victoria College, the predecessor of the University of Victoria, from 1960 to 1961 before completing a Bachelor’s of Arts at the University of Toronto and a Doctoral Degree at Princeton University (Harvey 104). Afterwards, she led an impressive career in both academics and politics, conducting important research in economic sociology—particularly regarding the socio-economic conditions of women’s labour in Canadian History (“Lorna Marsden, C.M., O.Ont.”). Amongst other distinctions and accolades, Dr. Marsden has received the Order of Canada, the Order of Ontario, and five honorary degrees including an Honorary Doctor of Laws from the University of Victoria. She also sat on Pierre Eliot Trudeau’s Liberal Senate and served as the President of both Wilfred Laurier and York University. For more on Dr. Marsden’s numerous accomplishments, see her profile on “The Council of Canadian Academies.”

As the inscription on the front free-endpaper indicates, Dr. Marsden's mother Grace owned The Girl’s Own Paper Supplementary Volume for fifty years before passing it on to her daughter. Grace Bosher (1903 – 1999) was born as Grace Simister in Salford, Lancashire; she immigrated to Canada with her parents, John Francis and Martha (Marsden) Simister, and her six siblings between 1911 and 1912 (“Canadian Census for 1911”; “Census of England and Wales for 1921”; “Simister Interview”).1 In order of birth, the Simister siblings were: Ruth, Norman, Margaret Vera, Martha, Grace, and Annie Augusta (“Census of England and Wales for 1901”, “1911,” “Canadian Census for 1921”). An elder sister, Frances Muriel, died in Salford at the age of fifteen shortly before the family emigrated to Canada (1910) (“Death Records for 1910”). Grace Simister married John Ernest Bosher in 1928 and lived most of her life in Sidney and North Saanich (BC Statistics “RG: 1928”). She died in February 1999 and is buried at the Holy Trinity Anglican Cemetery in North Saanich.

Grace Bosher’s “devoted sister / Pattie” was Martha (Simister) Mitchell (b. 1901) (“Canadian Census for 1911”; “Census of England and Wales for 1921”; “Simister Interview”). Martha likely went by the nickname Pattie because she shared a forename with her mother, Martha (Marsden) Simister. Pattie Simister married Clarence Ewart Bosher in 1929, and according to Dr. Marsden, they “lived in various parts of Victoria and Nanaimo and at one point in Nanaimo” (BC Statistics “RG: 1929”)

Public records data can help piece together an outline of the narrative of the book’s ownership: Pattie Simister, at age 17 gave this book to her little sister Grace, then 15, for Christmas. Later in her life, Grace gave the book to her own daughter, Lorna Marsden. This timeline emphasizes the personal history of this book and its links to historical people, then recasts the object as a record of kinship. However, while helpful for reconstructing a basic timeline of social exchange, these governmental papers do not tell us much about the story of the book. For this reason, I return to the inscriptions on the front free-endpaper. Alongside the inscriptions of ownership, someone (potentially Pattie) wrote “R. I. P.” in the upper-left corner next to the inscription in blue. Four mourning quotations follow Pattie’s address to Grace. They are: “To one we love so dearly”; “gone but not forgotten” and two poetic extracts by Oliver Goldsmith and Walter Scott: “A kind and gentle heart she had / To comfort friend and foe / Goldsmith”; and “And ne’er did Grecian chisel trace / A nymph or naiad or a grace, / of fairer form or lovelier face / Scott.” The context behind these quotations is likely lost to time because they are lacking specific dates of the inscription. Furthermore, I cannot consult the original owners. If I were to speculate based on information from British and Canadian census reports, I would postulate that these quotations relate to the death of their elder sister, Frances Muriel Simister. When Pattie Simister gave this book to her younger sister in 1918, Grace was the same age that Frances was when she passed away in 1910. Perhaps, then, the book was given as a gesture of commemoration. If this is the case, then it particularly important that the supplementary volume only contains issues from the years following Frances’s death, and that these years that coincided with the family leaving or “losing” their home in Lancashire. Even though I cannot ever uncover the book’s precise context of mourning and exchange, the effect of these inscriptions on the front free-endpaper remains the same. The mourning quotations emphasize a second context of use and exchange wherein the book can be refigured as an “artefact of elegy”— an object that is “encode[d] with a sense of loss and dislocation characteristic of elegy” (Zytaruk 320). More broadly, the Simister sisters’ handwriting attributes a biographical context of memory and loss onto the book object. To use Gosden and Marshall’s term, the front free-endpaper “links” the book to Dr. Lorna Marsden, to Grace Bosher, and to Pattie Mitchell (173). These people are concurrently linked to a matrix of external paper traces which themselves become part of the book’s biography. The Simisters’ stories are paradoxically present in the book’s materiality by virtue of material traces of absence.

.1 British Census reports from the early twentieth century fall under Crown copyright and cannot be reproduced in this Omeka page. The 1901 and the 1911 Lancashire census reports that I referenced can be consulted online with a paid subscription to Ancestry.com.

✧✧✧

In a telephone interview on 10 December 2017, Dr. Lorna Marsden confirmed that this supplementary volume of The Girl's Own Paper once belonged to her and that it circulated within her family. She remembers growing up in a house filled with books, and that her family owned multiple copies of both The Girl’s Own Annual and The Boy’s Own Annual. Dr. Marsden said that she read these books a lot; they intrigued her because they represented an “exotic past” but also because they detailed “an era where women were increasingly becoming independent white collar workers” instead of being relegated to the domestic sphere (Marsden).

Dr. Marsden did not know who the mourning inscriptions pertained to. She offered that the volume might have originally belonged to her Grandmother’s half-sister, Annie Marsden (1860 – 1947) who emigrated with them to Canada (Marsden). In this interview, Dr. Marsden also suggested that the original book was probably acquired second-hand in Victoria, either by Pattie Simister or by Annie Marsden. The pages of The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume hold no obvious traces of ownership other than those of the Simister family, which means that for now, its life story before Christmas of 1918 is unfortunately lost to time.

Are you interested in learning more about the Simister family? The BC Archives at the Royal BC Museum holds two sound recordings pertaining to the Simister sisters. In a 1981 interview with Priscilla Jay, the eldest Simister sister, Ruth Anstey, shares her memories of the family’s immigration. And, in a 1973 interview with Elizabeth (Bosher) Gould, Ruth Anstey, Pattie Mitchell, and Grace Bosher discuss their first impressions of Sidney and Victoria. The latter recording is filed away in cool storage for preservation and is not available for immediate reference, but a second copy might be obtainable from the original donors at the Victoria Historical Society (Wardle). Protocols for accessing the Ruth Anstey interview can be found on the BC Archives website.

IV. Printing and the Story of Production

Many pages of The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume are intended to be used as well as read. Instructional articles on cookery and sewing were often removed from the book and consulted in the context of craft. These removals are seldom clean. They leave behind rips, tears, and other material traces of use and absence.

Fig. 20: Front cover of The Girl's Own Annual (1916).

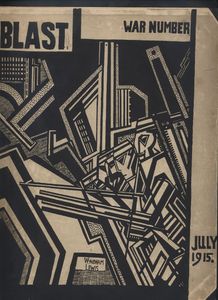

Fig. 21: Front cover of BLAST (1915).

Fig. 22: Front cover of The Strand Magazine, vol. 1 (1891).

V. Further Reading

Are you interested in learning more about The Girl's Own Paper and The Girl’s Own Annual? The University of Victoria’s Special Collections has more than thirty copies of The Girl’s Own Annual and the accompanying Boys Own Annual. Protocols for access can be found on the Library website.

If you cannot get to Victoria, I encourage you to seek out these titles at your local Archives and Special Collections. Otherwise, Terri Doughty’s Selections from the Girl’s Own Paper 1880–1907 reprints and contextualizes many of the original texts and would be a great place to start your research. A partial version of this book is available on Google Books. Some of the earlier issues of The Girl’s Own Paper can also be accessed on Project Gutenberg.

For more scholarly articles on The Girl’s Own Paper, please see the Works Cited list below.

Are you interested in learning more about object studies? Peter N. Miller’s short article “How Objects Speak” in The Chronicle of Higher Education provides a compelling and accessible introduction to the field.

Are you interested in British periodicals that were contemporaneous with The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume? Many of the avant-garde aesthetic movements of the nineteen-teens were fostered in periodical culture. For a stark contrast to The Girl’s Own Paper, see LO and TF’s excellent Omeka pages on BLAST: The Review of the Great English Vortex and The War Number. These two texts have been fully digitized; they, along with many others, can be accessed via the Modernist Journal’s Project.

Are you interested in Victorian periodicals? The University of Victoria’s Special Collections has impressive holdings in British Periodicals of the long nineteenth century. To get a sense of our various titles, see KF’s work on The Strand, EHG’s work on All the Year Round, JN’s work on Household Words, PW’s work on Bentley’s Miscellany, and KB’s work on Woman’s World. If you prefer to do your research online, check out the digitized periodicals at the Nineteenth-century Serials Edition, the Yellow Nineties, and Dickens Journals Online.

Are you interested in alternative uses for books? See JE’s page on fold-out maps in Captain Cook’s Voyage to the Pacific Ocean.

Is The Girl’s Own Paper just not really your thing? Do not fear! The Moveable Type exhibit has an ever-growing variety of remediated Special Collections materials. See, for example, TG’s compelling work on the late twentieth-century feminist and queer magazine Heresies.

Regardless of your interests, I hope that this Omeka page has piqued your interest in the wealth of bound print material held at the University of Victoria’s Special Collections. Moreover, I hope that this page has convinced you that books are material objects with unique life stories that can span multiple simultaneous contexts. Just like this tattered and humble volume of The Girl’s Own Paper, the books on your shelves may yet have stories to tell.

VI. Acknowledgments

I extend my utmost thanks to Dr. Lorna Marsden for sharing her thoughts and memories with me and for helping me uncover the story of this very special book.

I am also indebted to Heather Dean, Katharine Mercer, Lara Wilson, John Frederick, and to the staff members at the University of Victoria’s Digitization Centre and Special Collections. This project would not have been possible without the collaboration and support of the Library.

Finally, I would like to thank Dr. Alison Chapman and the Fall 2017 English 500/A01 cohort for their thought-provoking questions and valuable suggestions throughout the term.

✧✧✧

VII. Works Cited

Atkinson, David, and Steve Roud. Street Literature in the Long Nineteenth Century: Producers, Sellers, Consumers, Cambridge Scholars, 2017

British Columbia Vital Statistics Agency. RG: 1928-09-331410; BCA: B13755; GSU 2074508, Ancestry.com

—. RG: 1929-09-348325; BCA: B13757; GSU 2074553, Ancestry.com

Census Returns of England and Wales, 1901. RG13; Piece: 3715; Folio: 105; Page: 5, The National Archives of the UK, 1901, Ancestry.com

Census Returns of England and Wales, 1911. District 465, Piece: 23945, The National Archives of the UK (TNA), 1911, Ancestry.com

Dannehl, Karin. “Object Biographies: From Production to Consumption.” History and Material Culture, edited by Karen Harvey, Routledge, 2009.

Dean, Heather. "Re: Engl 500: Inscription Question." Received by KF. 15 September 2017.

Doughty, Terri. Selections from the Girl’s Own Paper, 1880–1907, Broadview Press, 2004.

Gasgoigne, Bamber. How to Identify Prints: a Complete Guide to Manual and Mechanical Processes from Woodcut to Inkjet, second edition, Thames & Hudson, 2004.

General Register Office. “Death Records for 1910.” England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes. London, England: General Register Office, Ancestry.com.

Gosden, Chris, and Yvonne Marshall. “The Cultural Biography of Objects.” World Archaeology, vol. 31, no. 2, 1999, pp. 169–178.

Harvey, Edward, ed. The Landsdowne Era: Victoria College 1946–63. University of Victoria P, 2008.

Howard, Jennifer. “Book Lovers Record Traces of 19th-century Readers.” The Chronicle of Higher Education, 5 May 2014.

Levy, Michelle, and Tom Mole. The Broadview Introduction to Book History, Broadview, 2017.

Library and Archives Canada. Sixth Census of Canada, 1921. Series RG31, Statistics Canada Fonds, Library and Archives Canada, 2013, Ancestry.com.

“Lorna Marsden, C.M., O.Ont.” Council of Canadian Academies, n. dat., http://www.scienceadvice.ca/en/assessments/completed/women-researchers/expert-panel/marsden.aspx.

Marsden, Lorna. Telephone Interview. 9 December 2017 [13:34–13:45 PT].

—. “Re: UVic Book Project: English 500.” Received by KF. 10 December 2017.

Miller, Peter N. “How Objects Speak.” Chronicle of Higher Education, 11 August 2014.

Mitchell, Sally. The New Girl: Girls’ Culture in England 1880–1915. Columbia UP, 1995.

Moruzi, Kristine. “The Healthy Girl: Fitness and Beauty in the Girl's Own Paper (1880–1907)." Constructing Girlhood through the Periodical Press, 1850–1915, Ashgate, 2012, pp. 54–83.

Patton, Cynthia Allen. “‘Not a Limitless Possession’: Health Advice and Readers' Agency in The Girl’s Own Paper, 1880–1890.” Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 45, no. 2, 2012, pp. 111–133.

Rodgers, Beth. “Competing Girlhoods: Competition, Community, and Reader Contribution in The Girl’s Own Paper and The Girl’s Realm.” Victorian Periodicals Review, vol. 45, no. 3, 2012, pp. 277–300.

“Simister sisters interview.” Item AAAB1610, T1461, BC Archives Online Catalogue, http://search-bcarchives.royalbcmuseum.bc.ca/simister-sisters-interview.

Sixth Census of Canada, 1921. Series RG31, Statistics Canada Fonds, Library and Archives Canada, 2013, Ancestry.com.

Sleeman, Elizabeth. The International Who’s Who of Women 2002. 3rd edition, Europa P., 2001.

Stauffer, Andrew. “About.” Book Traces, http://www.booktraces.org/about/, accessed 9 December 2017.

The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume. Edited by Flora Klickmann, Religious Tract Society, [1915].

The Girl's Own Paper. The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume, edited by Flora Klickmann, Religious Tract Society, [1911], pp. 1–54.

---. The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume, edited by Flora Klickmann, Religious Tract Society, [1912], pp. 1–62.

---. The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume, edited by Flora Klickmann, Religious Tract Society, [1914], pp. 1–48.

---. The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume, edited by Flora Klickmann, Religious Tract Society, [1915], pp. 1–48.

Tretyakov, Sergei. “The Biography of the Object.” October, edited by Rosalind Krauss, Annette Michelson, et al., no. 118, 2006 [1929], pp. 57–62.

Ward, Honor. “About The Girl’s Own Paper.” The Girl’s Own Paper Index, developed by Tom Ward, Lutterworth Press.

Wardle, Diane. "Re: BC Archives Inquiry - 23160-20/V - Access to sound recording AAAB1610 (T1461:0001) - Simister sisters interview." Received by KF. 29 November 2017.

Zytaruk, “Artifacts of Elegy: The Foundling Hospital Tokens.” Journal of British Studies, vol. 54, 2015, pp. 320–348.

✧✧✧

KSHF, Fall 2017.

![Gatherings and spine of <em>The Girl's Own Paper: Supplementary Volume </em>[1915] Gatherings and spine of <em>The Girl's Own Paper: Supplementary Volume </em>[1915]](../../../../files/square_thumbnails/d3beca74959e505cdeb004b2fd6662bb.jpg)

![Editor's Page in the First Issue of <em>The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume </em>[1915] Editor's Page in the First Issue of <em>The Girl’s Own Paper: Supplementary Volume </em>[1915]](../../../../files/square_thumbnails/ef2d45f41be371346307fac6f7460833.jpg)