Ann Radcliffe, The Romance of the Forest (1835)

CONTENTS

1 Introduction and Methods

2 The Living Text

3 The Dying Text

4 Publication

5 The Print Surge

6 Digital Negligence

7 Works Cited

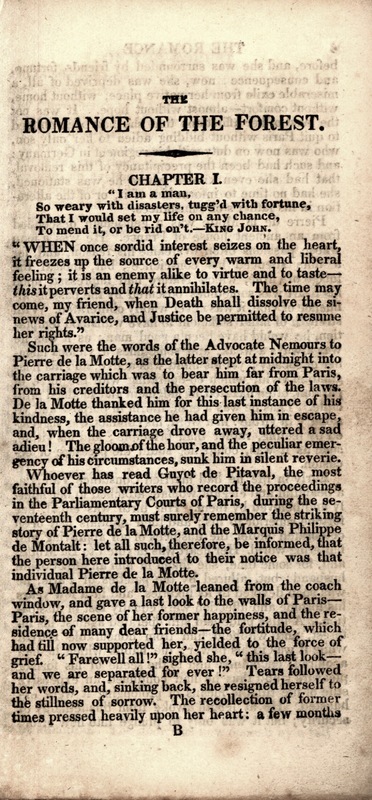

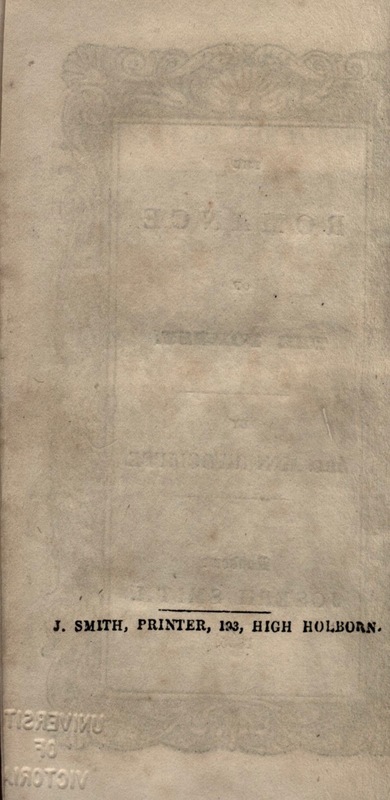

Frontispiece for Joseph Smith's 1835 edition of The Romance of the Forest, with accompanying page number for the scene it depicts.

Ere the bat hath flown

His cloister'd flight; ere to black Hecate's summons,

The shard-born beetle, with his drowsy hums,

Hath rung night's yawning peal, there shall be done

A deed of dreadful note.

MACBETH.

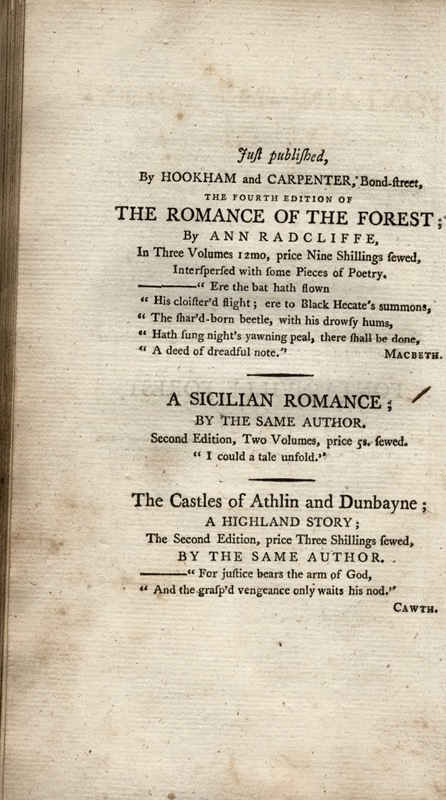

Epigraph to Ann Radcliffe's The Romance of the Forest as it appears in the first edition, published by T. Hookham and J. Carpenter in 1791. This Shakespearean quotation is absent from the title page of Joseph Smith's 1835 edition (bottom right). Due to the fragility of the book, its pages could not be fully aligned in the scanning process, resulting in some image cut-off and uneven positioning. As discussed below, this page prioritizes benign handling of the print object as much as possible while providing partial digital access.

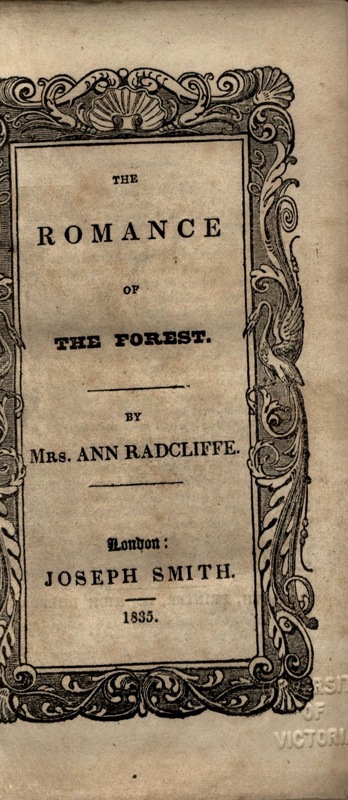

Title page for Smith's edition. Digital study of fragile nineteenth century books requires a balancing act of providing access while avoiding exacerbation of disintegration and decay.

1 Introduction and Methods

This Omeka page examines Joseph Smith's 1835 edition of English novelist Ann Radcliffe’s The Romance of the Forest (1791), a gothic novel by an author who is variously dubbed “the great enchantress” and “the Shakespeare of Romance writers” (Miles 7). This page focalizes a particular copy of Smith's edition of the novel—a pocket-sized, economical print object that is significantly decayed from aging and use—because it offers an entry point into considerations of the proliferation of print culture in England during the long nineteenth century, and the continued survival of such books in the digital age. In particular, this page is concerned with questions of access to nineteenth century print materials, and follows in the methodological footsteps of another in the Moveable Type exhibit: The Girl's Own Paper: Supplementary Volume [1915], particularly in its invocation of the spirit of Andrew Stauffer's NINES-sponsored Book Traces project, which prioritizes the material dimension of book studies by seeking out copies of nineteenth and twentieth century books that bear human traces. Like The Girl's Own Paper page in this exhibit, the object focalized here is already included in the University of Victoria's Special Collections, and therefore outside the scope of Stauffer's project. However, Smith's edition is just such a nineteenth century book that exhibits a particular history of personal use.

Stauffer argues for a conceptualization of a book "as an historical record that is always already incarnated, each body bearing traces of its many social interactions and it long journey into our hands" (336). This page likewise approaches the book as a kind of living—and dying—body which bears marks of age and origin as much as the people who hold it. Working from the research of William St Clair, Simon Eliot, and Rob Banham on book history in Great Britain, with reference to literary research on Ann Radcliffe by Chloe Chard, Robert Miles, and Markman Ellis, this page situates Joseph Smith's edition in the context of nineteenth century reading and print culture, while also documenting the book's deterioration in order to understand it as a print object that, like all others, has a finite material lifespan eloquent of its role in society. A central aim of this page is to provide partial access to a nineteenth century book that, while not of the highest quality of manufacture, is nonetheless a culturally significant print object worthy of consideration as such. That is to say, it is an object of cultural signficance for its material composition as well as its content. This page regards the physical body of Smith's 1835 edition as connected to larger networks of the cultural and industrial history of printing, and does so with an ethics of care—seeking to strike a balance between digital representation and harm-averse handling of the object itself. As section 6 of this page discusses, these two priorities do not always align in digital textual studies. Consequently, scanned digital surrogates for certain pages of the book were produced with an aim to cause as little further deterioration as possible, resulting in minor image cut-offs and, because straightening the images would have resulted in cropping, some uneven positioning. To flatten or press the book for the sake of a fuller image would have caused greater damage to an already precarious book, and this page favours high-resolution scans over photographs where possible.

Readers of Ann Radcliffe will know that the novel’s plot concerns Adeline, a heroine of mysterious origins who takes refuge with the family of a morally suspect patriarch fleeing legal prosecution in Paris, and is abandoned to the designs of a malicious libertine. The family ends up residing in the dilapidated and possibly haunted ruins of a medieval abbey on the edges of the forest of Fontainville. The novel’s narrative structure becomes increasingly elaborate and concludes in a mode akin to the highly crafted plot resolutions of Shakespeare’s romance plays, with Adeline’s ultimate deliverance from harm into virtuous safe harbour. This copy of The Romance exhibits an elaborate history of its own, even if it cannot be ultimately clarified to the same degree as that achieved by Radcliffe’s self-termed mode of “the supernatural explain’d” (Ellis 66). This page explores how the physical print objects which contain Radcliffe's narrative do not always fare as well as the heroine it concerns. Commenting on Radcliffe's capacity to entrance her readers for The Critical Review in 1792, Samuel Taylor Coleridge praised The Romance of the Forest, stating "the attention is uninterruptedly fixed, till the veil is designedly withdrawn" (Ellis 51). This page seeks to unveil some of the curiosities of this laboured little book.

Note: Minor editing of scanned images was performed, altering lighting and colour contrast for the sake of on-screen clarity. This page attempts, as much as possible, to accurately represent the experience of holding and regarding the physical book, but such endeavours are always to some extent limited by the digitization process. Thus, this page should be understood to reflect a series of representational choices in the partial remediation of a print object for online access. This is true of all digitization, regardless of how sophisticated the technology involved.

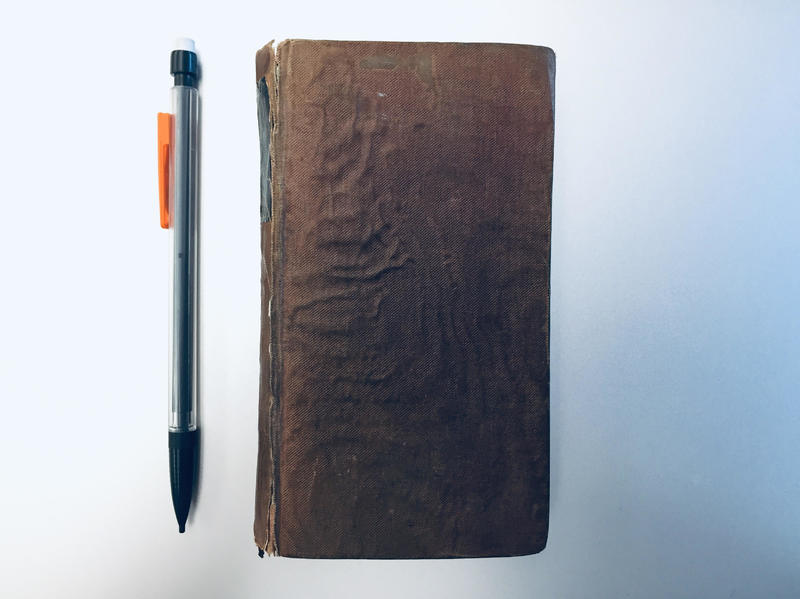

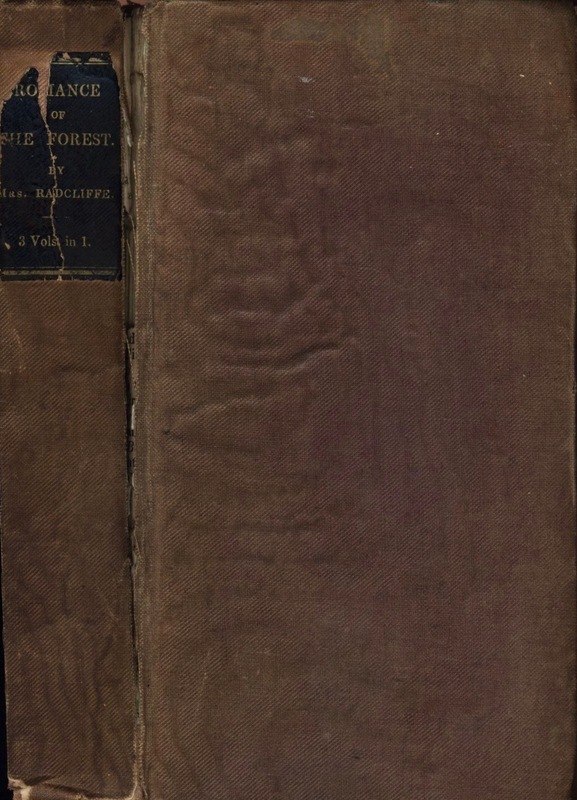

Cover of Smith's 1835 edition of The Romance of the Forest, with mechanical pencil for scale.

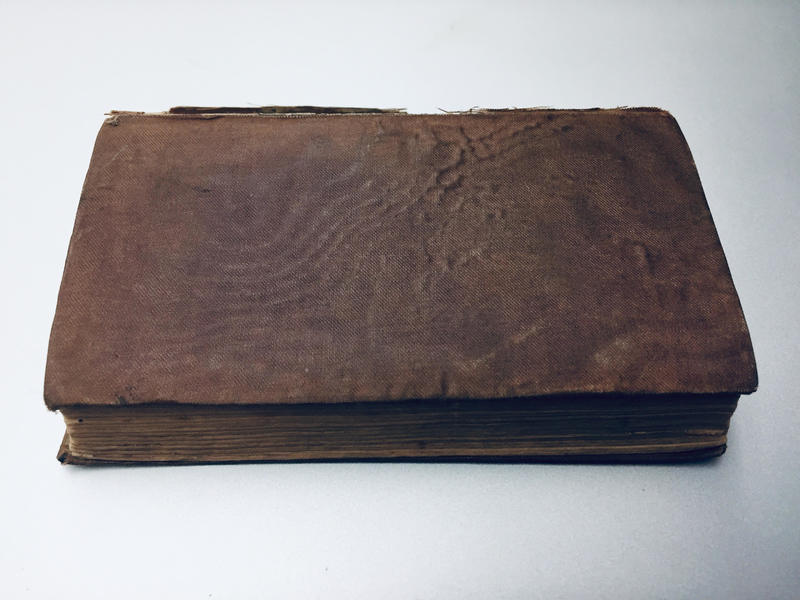

Exterior view of the book: back cover and pages.

The signature of an "F. W. Buraglo" provides partial knowledge of at least one previous owner.

2 The Living Text

The physical character of the book is this page's primary entry point into consideration of its lifespan and relation to both personal use and cultural position.

The stature of Joseph Smith's 1835 edition of The Romance is eloquent of its purpose: pocket-sized, portable, and relatively affordable reading material. The book's dimensions are as follows: 7.3 cm wide, 14.3 cm long, and 16 cm diagonally. From front cover to back its thickness amounts to 2.5 cm. The left-hand topmost photograph is illustrative of the facility with which the little book can be carried, approximately matching the length of a mechanical pencil. Size alone does not guarantee knowledge of the history of this particular copy—it may well be that it never travelled far beyond a damp room—but these dimensions suggest this book wasn't designed for reverence but was adapted to transport and ease of use.

The book's unremarkable exterior—cloth-bound in a dull brown, without ornamentation—further instantiates its economical design. Its spine is unadorned save for a simple title marker, now significantly worn, with faded gold type on a black background reading: "Romance of the Forest. By Mrs. Radcliffe. 3 Vols in 1." Other than a couple of horizontal lines matching the font colour at the top and bottom of this marker, it is plain. The advertisement born on its own spine of containing three volumes in one affirms the book's economy, and implicitly bears the promise of a substantial reading experience—a multi-volume work of prose fiction—within a single container. The text copy is printed in a legible, open-face serif type, however it is significantly compacted to accomodate the small page size (see section 5 for image example).

These physical attributes of the book illustrate the novel's status as a popular text. As section 4 of this page discusses, The Romance of the Forest was an immense commercial success, and its author's profile was increasing at its time of publication, despite the anonymity of the first edition's title page. Smith's edition of the novel speaks to the demand for this kind of title. A compact edition like this one, containing all three volumes of the text, fashioned from relatively inexpensive materials (cloth as opposed to leather, small page size as opposed to large and luxurious), is somewhat more attainable in a period when books retained luxury status.

According to Eliot, in the early nineteenth-century volumes of novels cost between 5s and 6s—a three-volume known as a “three-decker” cost been 15s and 18s (291). During the same period, a skilled builder earned a weekly average of 21s, a printer 27s, and a teacher 17s, so that "the buying of a new novel for most of the population was an unaffordable luxury" (291). Eliot notes that by 1821, “Constable, the publisher of Sir Walter Scott, had traded on his popularity by bumping up the price of each volume to 10s 6d, thus pricing a three-decker novel at 31s 6d: more than the average weekly wage for most of the nineteenth century" (291). Cheaper editions of novels sometimes took significant amounts of time to arrive (291). Smith’s pocket-sized edition of The Romance, one in a series of later editions of Radcliffe’s novel from various publishers, would doubtless have sold for far less than a new Walter Scott novel, but while it was likely economical as compared to first editions published in the same period, it would have remained out of reach to large swaths of the population.

Such economic barries do not necessarily detract, however, from the reading history of this particular book. St Clair notes that "the Edinburgh Review believed that the average multiplier for a new title in the romatic period was about one to four" (235). According to St Clair this figure was likely based on a particular vision of a well-to-do household including children, unmarried or widowed sisters, governesses present for oral readings, and possibly servants (235). Though speculative, this multiplier suggests the possibility of numerous readers for Smith's 1835 edition, even in the early years of its life. Judging by its advanced dilapidation, such use may well have compounded with the passage of time.

Despite its mundane appearance, the book provokes curiosity. Numerous questions arise concerning its prior ownership and history—not simply the history of its production, its place withing the print industry of the nineteenth century, or within Radcliffe's oeuvre—but its history of being read by particular individuals, the responses they had to its content, the resonances of its cultural knowledge among those readers. This page cannot answer all of these, but examines the material evidence of the text to draw some tentative conclusions.

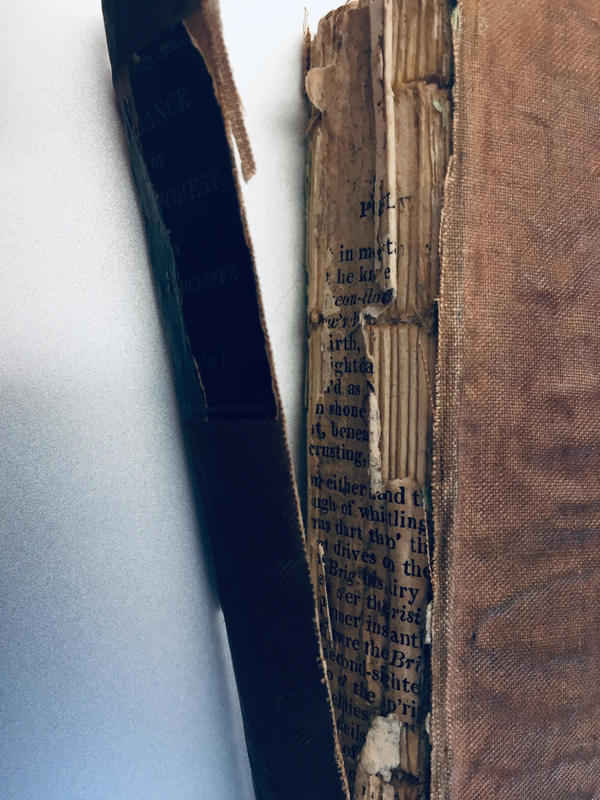

Textual cannibalism: beneath the nearly detached spine of the book's binding, pages recycled from other print material.

The book's fragility at this stage precludes the casual reading for which it was likely originally intended—it must be handled with utmost care.

Scanned image of the cover and spine of Smith's 1835 edition. Its spine is barely attached to its front cover at this point and falls flat if not held up.

3 The Dying Text

Handling this copy of Smith's edition requires significant delicacy. The unfortunate condition of this book is an advanced state of disintegration. Close examination of book's cloth binding reveals it is particularly brittle. Nearly two centuries since its publication, the book's state of decay is its first impression.

At the time of this Omeka page's publication, the book's binding is virtually in tatters. The spine is barely attached to the front cover, hanging on by a small frayed section at the tail. The back cover is fully torn from the rest of the binding. The cloth of the binding exterior is thoroughly warped, likely from exposure to moisture: the surface is rippled to the touch, scuffed, exhibiting an appearance not dissimilar to varicose veins. Moisture damage is also evident in the spotted appearance of many pages in the text block. The fore edge is the colour of old toffee. Overall, the book is particularly fragrant with age.

The text block is altogether detached from the binding, a regrettable fact of the book's current state of disrepair but one that enables some fruitful views of the book's inner components. For instance, beneath the spine and layered directly onto the bound sections (or gatherings) of the text block are jumbled strips of paper from other publications, used as filler in the binding process. The paper and typeface of these strips are a close match to that found in the text block, though the type is not precisely identical and contains fragments of lines not found in the text of The Romance. This spine filler was likely recycled from other publications from the same publisher, a practise which evidences the avaricious economics of the print industry during the period—if one publication didn't sell, its materials could be fed directly into another. (For a closer look beneath the spine, see top two photos in this section.)

A post-publication physical alteration is evident in the book's text block and binding. At some stage in its ownership, the lining pages between text block and binding were replaced with a lighter, bright green paper, likely to reinforce the book's structural integrity. The latency of these pages is evident in their differing composition as well as the original paper attached to the binding beneath, visible due to its being torn. The text block is also coming undone—its final gathering has come loose from the rest.

Any further use of the book, except as an object of bibliographical study, would before long result in its complete dismemberment. This copy of Smith's edition is now well past the days it would have been casually taken up and, quite likely, carried around, but nonetheless has much to say about the period that produced it. Working with the book in its current condition invites a consideration of the rise of popular fiction in print books in the nineteenth century that extends beyond study of print histories in modern research—this book confronts a researcher directly with the sensation of its material reality, its age, its decay. Further descriptive bibliographical work on this object would doubtless reveal more about its provenance and the specific conditions under which it was produced. With reference to Stauffer's argument that the nineteenth century book is increasingly under threat of isolation from both public and scholarly access to direct study in the age of digitization (335), this copy of Smith's edition embodies many of the features which can't be reproduced by digital surrogates, and which could be lost on the scholar who relies primarily on digital texts: the physical experience of book size, material composition, overall condition, and the history of use evident in its dilapidation. The trouble is, how do we find a way to work with this material without worsening the already precarious condition that is partly the value of examining it in the flesh? The more this researcher handled the book, despite taking every reasonable precaution, the more its edges frayed. Every page this researcher opened invited the risk another gathering of the text block coming loose. Digitization of aspects of the text presented similar challenges, already discussed above. This Omeka page does not have a definitive solution to the conundrum of studying fragile nineteenth century texts in the digital age, but it should be noted that the material value of the text is lost if it is never handled.

The publisher's London address on the back of the title page.

Publication advertisement detailing Radcliffe's available works from Hookham and Carpenter in the 1794 first edition of James Boaden's stage adaptation of The Romance of the Forest.

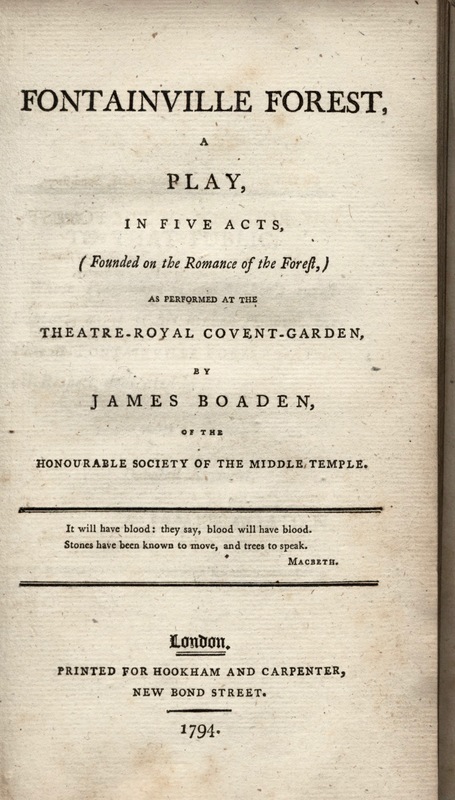

Title page for Boaden's Fontainville Forest. The enormous popularity of The Romance of the Forest is evident by its numerous editions and adapted forms like this one only four years after original publication.

4 Publication

In the chronology of Ann Radcliffe's novels, The Romance of the Forest is the third of five published in her lifetime:

The Castles of Athlin and Dunbayne (1789)

A Sicilian Romance (1790)

The Romance of the Forest (1791)

The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794)

The Italian (1797)

Gaston de Blondeville (posthumous, 1826)

Radcliffe's first three novels were all published T. Hookham & J. Carpenter, based in London. The two novels that followed during her lifetime, as well as the third posthumously published, came from three different London based publishers: The Mysteries of Udolpho from G. G. and J. Robinson, The Italian from T. Cadell Junior and W. Davies, and Gaston de Blondeville from Henry Colburn. As discussed above, The Romance of the Forest orginally arrived anonymously in three volumes, a fact which Smith's 1835 edition advertises on its spine ("3 Vols in 1"), communicating good value.

Its publication would signficiantly transform the author's life and career. Ellis notes that Radcliffe (née Ann Ward) recoiled from the idea of public notoriety, but it was difficult to avoid after her name was attached to her novels (49), and The Romance of the Forest marked a turning point in the commercial success of her writing (49). According to Ellis, the popular acclaim of her third novel led to increasingly lucrative payments for her next two: £500 for The Mysteries of Udolpho and £600 for The Italian (49). These were "enormous sums for the period" (49).

The Romance of the Forest coughed up money, to be sure, but also critical recognition. According to Chard, the novel "was received by contemporary reviewers with an enthusiasm rather greater than that which greeted either [The Mysteries of Udolpho or The Italian]" (ix). As mentioned in section 1 of this page, Coleridge's review of the novel praised Radcliffe's craftsmanship and ability to arrest the reader's attention (Ellis 51). This skill on her part was no doubt a factor in the quick spread of her third novel's popularity, even beyond its own genre.

From the first edition onward, The Romance proliferated with increasing force; long before Smith put out his 1835 pocket-size edition, Radcliffe's novel had already seen numerous editions as well as adapted forms. The diffusion of this title can be understood in harmony with the larger surge of print material in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries discussed in section 6 of this page.

A 1794 edition of playwright James Boaden's theatrical adaptation of the novel, Fontainville Forest: A Play in Five Acts (Founded on the Romance of the Forest,) as performed at the Theatre-Royal Covent-Garden, provides primary evidence for its commercial and cultural appeal. Also from T. Hookham & J. Carpenter, the published Boaden adaptation contains an advertisement preceding its title page for other works "just published" by the firm. First billing goes to the fourth edition of The Romance of the Forest: "In Three Volumes 12mo, price Nine Shillings fewed, Interspersed with some Pieces of Poetry." The advertisement lists Radcliffe’s first two novels afterward in reverse chronology. The advertisement presents these earlier publications, however, in only their second editions. The Romance of the Forest, then, saw a new edition in each of the four years following its first—twice as many as each of her previous endeavours. Add to this Boaden's stage adaptation and it is safe to conclude that with the tortured tale of Adeline de Montalt, Radcliffe broke through as a commercial and critical juggernaut.

The overall increased productivity of the printing industry in Great Britain is bound up with the history of this literary sensation. Radcliffe's novel is an identifiable contributor to the larger networks of print culture that exerted a shaping influence on British society at the time of its publication in both original subsequent editions. Section 5 of this page examines the proliferation of The Romance in relation to larger networks and economic conditions of the print industry in the decades leading up to Smith's 1835 edition.

5 The Print Surge

The publisher Joseph Smith's London address is listed on the back of the title page for his 1835 edition of Radcliffe's novel: 103 High Holborn, in the heart of the city that, according to St Clair, was one of two main manufacturing centres for books during the romantic period, along with Edinburgh (177). Smith's publishing firm would have been caught up in the technological innovations and societal transformations which reshaped the printing industry throughout the nineteenth century.

Paper was hand made during the period (178). According to St Claire, the battlefields of Europe were scavenged for the spare cloth which was processed into paper, to be sold in rag fairs and, ultimately, international markets (178). Cloth was collected from all available sources, ending up in the paper mills which proliferated along various British rivers (178). The resulting paper was "boiled, bleached, smoothed," and tends to remain "white and spotless" even into the twenty-first century (178). The copy of Smith's edition with which this page is concerned, however, shows noticable spotting, which may be an indicator of the conditions in which this particular book was hitherto kept more than anything else.

St Clair notes that the technological method for printing books at this time was virtually the same that had been in use since the fifteenth century: "Moveable metal type, each piece made individually by hand by a skilled craftsman, was set by hand by skilled printers who copied by eye. After the setting of the print, came the inking, the drying, and the pressing of the sheets, and then the folding, the stitching, and the binding" (178). However, according to Banham, technological refinements during the early 1800s introduced some new efficiencies to the process (274). During the first two decades of the nineteenth century, the iron printing press came to replace the wooden hand press which until then predominated (274). This new iteration of the printing press was invented by Earl Stanhope, c. 1800 (274). Yet more versions of the iron press followed—according to Banham, "the Columbian" and "the Albion" were the most successful of these (274). The iron press offered advantages over its wooden predecessor: it required less physical exertion, had greater and more evenly delivered pressure, had a larger platen (the plate that presses the type against the paper), and could print large forms with a single hand-pull (274). Banham notes that these were only minor improvements to overall efficiency (274), but the forward thinking nature of the iron press nevertheless indicates the general movement of the period towards greater print output.

Between 1790 and 1830 approximately 3000 new prose fiction titles were published in Great Britain (St Clair 172-3). The Romance of the Forest was among them, with its numerous editions and adapted forms soon to follow. Meanwhile, yet more technological innovations to the printing processing were forthcoming from the iron press, such as stereotype plates formed from molten metal poured into plaster moulds of the original moveable type (182). These could be retained for subsequent printings (182). According to St Clair, this technology was initially only put to use by the London publishing syndicates in the 1810s on titles "for which a continuing large demanded was expected at that time, reference works and dictionaries, and the bestselling anthologies and abridgements of the old canon, including school textbooks" (183). But if there was a popular novel which could have served as a contender for the new method, The Romance would have been it, considering its numerous editions. As the technology was refined in the late 1830s (184) it meant another new avenue for print proliferation in the nineteenth century, along with forthcoming invention of paper moulds and electrotypes (184). Even though Smith's edition of The Romance does not fit directly into this specific technological innovation, we can look to the popularity of Radcliffe's novel, manifest in the demand for his economical pocket-sized edition, as part of the larger print industrial surge, and contributing to justify impending technological changes in order to increase productivity and profit from the demand. At the time of Smith's 1835 edition, the industry-wide implentation of stereotyping was on the horizon, which due to a low melt-down value encouraged publishers to retain the plates until they were certain they were no longer needed, so that, as St Claire notes, "for the first time in history, a publisher could plausibly promise never to let a title go out of print" (184). Thus the popular novel was heading at this time toward potential status as a perpetual moneymaker—Radcliffe's novel, among others, was bound up in that promise.

6 Digital Negligence

As we have seen, Smith's 1835 edition of The Romance of the Forest is a material print object that speaks to multiple histories—that of its author, its owner(s) and readers, and the industrial conditions that produced it. It is also a book that can barely be handled at this time. As section 1 of this page discusses, the process of partially digitizing the book was inhibited by its gradually worsening state of decay. Currently housed in the University of Victoria's Special Collections, the book remains in relatively stable condition, yet even when summoning the utmost care, each instance of picking it up, thumbing its pages, producing scans, etc., threatened further harm: even slight touch contributes to the fraying of the already compromised binding, or the loosening of different sections of the text block. If we proceed from the basis that this book is a worthwhile cultural object, uniquely valuable for study of its material form, how do we encourage future researchers, book enthusiasts, or members of the general public to interact with it, knowing that each subsequent interaction contributes to its deterioration? This is a specialized question, as not all rare books held in Special Collections are in such precarious states—indeed, far older print objects of tougher manufacture endure with greater fortitude.

Stauffer writes that "out of copyright, often widely available, and frequently fragile due to poor paper quality, nineteenth century books are both richly served and particularly imperiled in the new media ecosystem" (335). He calls our attention to the "particularly conflicted" status of nineteenth century print materials in a digital age when Google Books surges ahead in multi-million title digitization endeavours, a process that yields undeniably useful methods of study, but can alter their status in libraries and archives, placing them "in a kind of competition with their own surrogates" (335-6). Stauffer warns against the loss of interaction with the physicality of books, arguing that "to understand the complex meaningfulness of nineteenth century literaure in its social, human character, we have to attend to the interface, which includes both the hardware of the physical book and the software of the many processes shaping its material forms and formats in an historical frame of reference" (336).

This page attempts to approach a particular nineteenth century book with these concerns in mind, seeking to navigate partial digital remediation of an exceedingly fragile print object in a way that centers physical attributes, while maintaining support for the opportunity of content-oriented research of text, author, genre, and literary movement. Moreover, this page promotes a method of digital study of print objects that embraces imperfection—scanned images here were produced with the intention that digital surrogates for aspects of the book are not replacements, but supplements, to its material study, and should therefore incur no further harm simply for the sake of a "better" file. This page moves towards a form of digital textual studies that does not lose sight of the priority of the material object. Stauffer writes that "much more work remains to be done on this aspect of the nineteenth-century book: the intersection of its content with its physical structures and evidence of use as ultimately productive of various layers of meaning" (340). This page presents Smith's 1835 edition of Radcliffe's novel as an opporutnity for just such critical work, inviting further interactions with the book, despite the inevitable problems of decay, while urging a renewed sense of sensible care in this encounter, whether for digital purposes or simply in the flesh.

7 Works Cited

Banham, Rob. "The Industrialization of the Book 1800-1970." A Companion to the History of the Book, edited by Simon Eliot and Joanathan Rose, Blackwell Publishing, 2007, pp.273-290.

Boaden, James. Fontainville Forest: A Play in Five Acts (Founded on the Romance of the Forest,) as performed at the Theatre-Royal Covent-Garden. Hookham and Carpenter, 1794.

Chard, Chloe. "Introduction." Ann Radcliffe, The Romance of the Forest, edited by Chloe Chard, Oxford University Press, 1986.

Eliot, Simon. "From Few and Expensive to Many and Cheap: The British Book Market 1800-1890." A Companion to the History of the Book, edited by Simon Eliot and Joanathan Rose, Blackwell Publishing, 2007, pp.291-302.

Ellis, Markman. The History of Gothic Fiction. Edinburgh University Press, 2000.

Miles, Robert. Ann Radcliffe: The Great Enchantress. Manchester University Press, 1995.

Radcliffe, Ann. The Romance of the Forest. Joseph Smith, 1835.

Radcliffe, Ann. The Romance of the Forest. Edited by Chloe Chard, Oxford University Press, 1986.

St Clair, William. The Reading Nation in the Romantic Period. Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Stauffer, Andrew. “The Nineteenth-Century Archive in the Digital Age.” European Romantic Review, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 335-341, doi.org/10.1080/10509585.2012.674264. Accessed 17 October 2018.

"The Girl's Own Paper: Supplementary Volume [1915]." Moveable Type: Print Material in Special Collections. Uvic Libraries Omeka Classic, www.omeka.library.uvic.ca/exhibits/show/movable-type/paper/girlsownpaper.

O.B./Fall2018