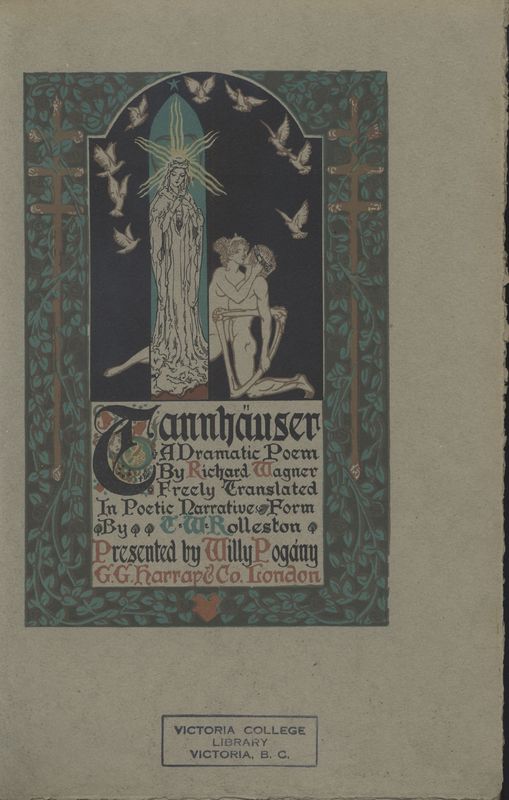

Tannhauser (1911) - A Dramatic Poem by Richard Wagner (1813-1883) Translated by Thomas W. Rolleston (1857-1920) Illustrated by Willy Pogany (1882-1955)

Introduction

Tannhauser is an opera by Richard Wagner, freely translated by T. W. Rolleston into English in poetic narrative form from the German libretto. Only 525 unpaginated copies of Tannhauser were published by G.G. Harrap and Co. in 1911 in London and the United States of America. It is illustrated by Willy Pogany, who has signed and numbered each copy. The examined Tannhauser in the Special Collections section at the McPherson library of the University of Victoria is number 298.

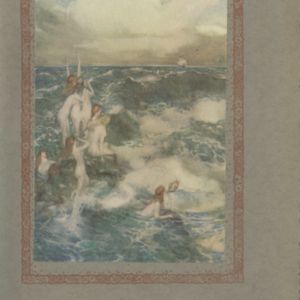

The frontispiece is the first tipped-in color-plate appearing in the book. It is surrounded by colorful floral designs.

From Fact to Fantasy

In composing the libretto of Tannhuaser, Wagner uses a variety of resources, combining myth and legend with historical events to create his desired story. According to Mary A. Cicora, Wagner distanced himself from modern works while also trying to refresh contemporary literature by investigating medieval literature, as he found it as to be more genuine. His search for older works is associated with a sense of nationalism to create a pure German composition. Cicora mentions that the existence of a poet by the name of Tannhauser is a fact, although there is not much information available about the details of his life. According to Mary Cicora, “Tannhauser fought in the Crusade of Emperor Friedrich II to Palestine in the years 1228-9” (16). What we know of Tannhauser, the poet and the knight, is based on his frequent references to himself in his songs, and it is not clear whether he actually experienced what he describes in verse. According to J.W. Thomas, there are places by the name of “Tannhausen” and it could be argued that the name Tannhauser is related to the poet’s place of birth and also the name “der tanhusere” meaning “the backwoodsman”. Also, since there are no titles in his name, he was not associated with any courtly family, castle, or town. Thomas argues that our information about Tannhauser is conjecture, and by taking into account the tone of the poet’s writings and his knowledge of the court, assumes that he was familiar with politics and the nobility of his time and he might have been a knight.

Wager’s Tannhuaser is more derived from the legend of the traditional ballad rather than the historical account. The fictional Tannhauser is a knight who is filled with sorrow of spending some time in Venusburg and goes on a pilgrimage to Rome to confess his sins to the Pope. The Pope claims that Tannhauser is damned for eternity and will never gain redemption, just as the staff in the hands of Pope will not sprout leaves ever again. Eventually, the staff sprouts leave and flowers, marking the redemption of Tannhuaser.

Wagner was also familiar with the legend of the song contest at the Wartburg, which he read about in the “Wartburgkrieg” poem. The poem is a mixture of fact and fantasy like the ballad and also appears in various versions and scopes. According to his autobiography Mein Leben and also Cicora (39), he does not use much of the song contest in the narration of his story. Cicora holds that this poem appears in two sections: “Sangerkrieg”, also known as “Furstenlob”, and the “Ratselstreit” (41). It is the “Furstenlob” part that inspired Wagner in his writing of Tannhauser (42). Wagner had also read Ludwig Tieck’s story “Der getreue Eckart und der Tannhauser” though he was not inspired by or liked it (Cicora 65). Cicora asserts that this first modern remedy of the Tannhauser legend was published in 1799 in volume one of Romantische Dichtungen. In Mein Liben, Wagner states that he was acquainted in his early youth with E.T.A Hoffmann’s story, “Der Kamp der Sanger” (Mein Leben 24). After investigating the writings of Wagner and his wife Cosima, Cicora explains that, despite Wagner’s fascination with writings, musical theory, and musical compositions of Hoffman, he is critical of Hoffmann’s portrayal of the Middle Ages and he does not consider “Der Kamp der Sanger” suitable for dramatization and as a source for creating Tannhauser (99-107).

Wagner was also acquainted with Heinrich Heine’s poem “Der Tanhauser”, but he does not mention his name in his writings on the subject of Tannhauser's sources. Cicora argues that Wagner’s neglect to give Heine credit can only be understood after noticing the influence of Heine’s works on Wagner’s literature and his deep admiration for him (130). Therefore, Wagner holds his pen from criticising Heine's Tannhauser like previous authors.

The title page of Tannhauser, which is including the name of contributors to the book and the publisher's name.

An Artistic Obsession

Tannhauser, Richard Wagner’s opera in three acts, is his only major unfinished project. Surprisingly, Cecil Hopkinson in his Tannhauser: An Examination of 36 Editions compares various publications of the opera published under Wagner's authorization, marking the obsession of Wagner with his Tannhauser. The various versions of Tannhauser are different in length of pages for both the libretto and the musical score with significant divergence in the layout of the acts, especially in its finale. Wagner never stopped changing the score of Tannhauser from the first performance of it in Dresden to the final years of his life when he had matured as an artist. The theme of the opera revolves around social conventions, religious doctrines, and redemption, brought about by true love, and otherworldly talent of an extraordinary artist. The protagonist of Tannhauser represents Wagner himself in many ways, such as his musical talent, his love life, and his conversion to Christianity. Three of the numerous versions of Tannhauser’s libretto are considered major turning points for their deviation, in textual and musical context, from their predecessors. Scholars consider three of the numerous versions of Tannhauser as turning points in the sea of changes, brought to its score by Wagner, based on their deviation in textual and musical contexts.

Critiques distinguish the outstanding iterations by the names of the cities where they were first performed. According to Cecil Hopkinson, Wagner finished writing Tannhauser by May, 1843 and published the first edition of the first version in May, 1845. He staged Tannhauser in Dresden on October 19th of 1845 for the first time in collaboration with C.F. Meser. He soon changed his mind and continued with a second version of the opera after the first night of its performance with eight nights in between. Seven years went by before the publication of the revised version in Dresden, which was advertised in number 9 of Signale for February 1852 by C.F. Meser (also known as Muller). The first edition of the third version, also known as the Vienna version, was published in 1859 in Dresden by C.F. Meser, which was announced in the Hofmeister’s Monatsberichte. Scholars refer to the fourth version as Paris version due to its publication and performance in French, in Paris. Wagner added a ballet scene to the first act. He also added the return of the pilgrims to the stage in the last scene, but this time with a revived staff in their hands, to frame the plot we know today. Wagner, in a letter to Franz List on 13 September 1860, expresses his joy in revising the last scene and hopes to improve his opera as a result. The full score of the Paris version was published in French by Gustave Flaxland in the August of 1861.The plot of the story in Rolleston and Pogany's collaboration is derived from the Paris version.

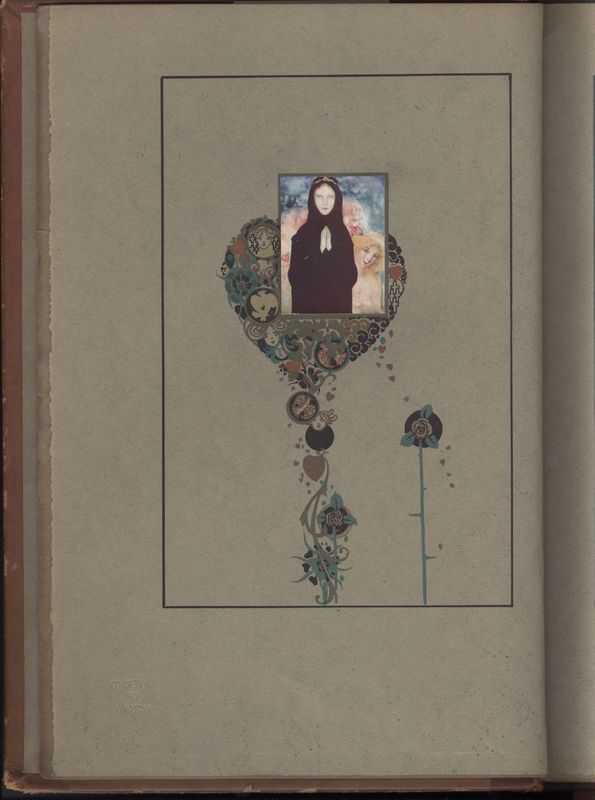

The blind stamped floral design on the vellum cover of the book is a harp, which has turned into a cross and then a symbol of a heart with leaves and flowers sprouting from it. This symbol beautifully intertwines the plot of Wagner’s story with the techniques introduced by the movement.

Art Nouveau

Holding and reading this edition of Tannhauser as a book is magical in many ways. The book is unpaginated and most of its pages are untrimmed, with many appealing illustrations on every page. It is a celebration of the efforts put into every aspect of creating a book, as a medium of sharing knowledge, from the contribution of an author to all processes concerned with its distribution such as print and publish. The floral design on its vellum cover prompts the reader to open the book while the illustrations compel one to flip the pages in search of more color and design. The illustrations in Tannhauser are not all designed for a mere description of the narration of the story. They also serve to provide a visual appeal in their presence as they celebrate book as a medium. Pogany's provides extensive designs and icons to create a total work of art while using an opera by Wagner who is amongst the first people who advocated the idea of total work of art.

Colors play a specific role in Tannhauser as they are blunt in their judgment of the settings and characters. Red appears for evil in contradiction to black and white, which represent the entanglement of good and bad in earthly life. Colors display contrast in both the setting of the poem as well as the protagonist’s duality. Besides the narration of the story, paintings portray mythological figures and religious symbols to suggest a connection between them. The appearance of the protagonist and other characters are divergent from page to page in form, colors, and costumes. Furthermore, the symbols and icons such as bird, cross, devil, harp, and heart appear in all sizes and shapes in random places with different colours.

The uniqueness of this edition of Tannhauser is linked to Art Nouveau, an international movement which aimed to vanish the line between fine and applied arts at the turn of the 19th century in Europe and the United States, especially in the art of illustration and decoration. Art Nouveau was also employed in architecture, ceramics, jewellery, furniture, glassware, poster, metalwork and many more fields. According to Alastair Duncan, Art-Nouveau is a movement that appeared in a confrontation with the mid-Victorian lifestyle and the way it touched society. It sought to “defeat the established order within the applied and fine arts” (7). Duncan asserts that William Morris (1834-1896) is the key figure responsible for the launch of the movement. Morris preferred the art and literature of Middle Ages over Renaissance and Classical Antiquity as he believed it to be the era before pollution of art and literature with mass production and consumerism. Duncan further explains that, for Morris, the machine was the source of evil because of its facilitation of mass production. As far as Morris was concerned, the machine is accountable for causing the human to lose his/her soul. Morris believes that machine brings banality and repetition to everyday life. Therefore, society has become a soulless machine which mass produces goods without any creativity. Machine devalued handcraftsmanship and faded the use of art in creating objects that are constantly used, such as furniture and containers. Duncan holds that Art Nouveau is inspired by the simplicity and minimalism of the two-dimensional Japanese art of painting and printing. Duncan identifies artists who were familiar with non-western art as precursors of Art Nouveau, such as William Blake (1857-1827) with his method of linear ornamentation and also his innovative paintings in his wood engravings and temperas for Songs of Innocence (1879) and Whirlwind of Lovers (1824-27) and also Aubrey Vincent Beardsley (1872-1898) with his illustrations of The Yellow Book.

According to Matteo Fochessati, decorative arts were overtly influenced by the movement followed by the expression of the term “the total artwork”, which was stressed by Henry van de Velde (1863-1957), who sought for art “a homogenous tension based on the equality of all component parts” (Fochessati 9). Fochessati explains that although Art Nouveau embodies the discontentment of Morris with the machine, it also celebrates the flourishing science and technology as they provide the artist with new material to work with. Artists employed the new inventions and knowledge to step away from past traditions.

Fochesati, in his reference to Japonisme, briefly mentions the impact of African art and Islamic art on the movement. However, overall, the influence was introduced to the west as Japonisme. In a more detailed examination of the origins of Art Nouveau, Paul Greenhalgh explains Morris’s fascination with figurative art of African and Middle Eastern countries such as Turkey, Syria and particularly Persia (Iran), in which “patterns are based on nature but sufficiently stylized not to appear three-dimensional and the forms of design enhanced and complimented the surface and type of object they decorated rather than obscuring it” (115). Greenhalgh further explains that the minimalism of Japanese art and the “whiplash curve” of Islamic art together “were melded into the full-blown Art Nouveau line” (116). Focchesati mentions the impacts of Wagner’s theory on the movement's effort for syncing fine and applied arts. By Gesamtkunstwerk, the total work of art, Wagner “sought to rebel against the predominance of music over drama in opera” (Magee 238).

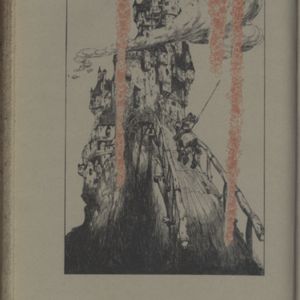

In his introduction to the phenomenon, Robert Schmutzler relates the use of narcissistic lines in Art Nouveau to seaweed or creeping plants, a technique used overtly in both the illustrations in Tannhauser and also in the initial letters in the beginning of the poem on each page. The undescriptive illustrations and the symbolic icons provide a visual appeal in reference to mythological figures as well as the religious symbols. They also provide a subtext to the text of the narration that represents the interpretations of the new authors of Tannhauser, the translator and the illustrator. In his illustrations, Willy Pogany utilises his knowledge of Art Nouveau and also Wagner’s operas to recreate the aural and dramatic aspects of dramatic art on paper. Just as Wagner uses leitmotifs in his music to recreate and recall the tensions of previous acts to the consciousness of the audience, Pogany uses icons, such as birds as a symbol of freedom and heart as a symbol of love to constantly remind us of the conflicts that Tannhauser is experiencing. Pogany’s use of colours is interesting in their opposition. He paints some birds red as a representation of Tannhauser’s sins and his search for freedom outside of social and religious conventions. In the scene of his reunion with Elizabeth, the earthly woman representing true love, the icons of black birds are dominant on the page as symbols of redemption through love. He also uses the colour red to resemble Venusburg and sin while white and black are representative of mortality and human dependence on experiencing joy and pain together.

Works Cited

Cicora, Mary A. From History to Myth: Wagner's Tannhäuser and its Literary Sources. Peter Lang, 1992.

Duncan, Alastair. Art Nouveau. Thames and Hudson, 1994.

Emslie, Barry. Richard Wagner and the Centrality of Love. Boydell Press, 2010.

Fochessati, Matteo. Art Nouveau: Between Modernism and Romantic Nationalism. 24 ORE Cultura, 2012.

Garrett, Leah. A Knight at the Opera: Heine, Wagner, Herzl, Peretz, and the Legacy of Der Tannhäuser. Purdue University Press, 2011.

Greenhalgh, Paul. Art Nouveau: 1890-1914. Harry N. Abrams, 2000.

Magee, Bryan. Wagner and Philosophy. Penguin books, 2000.

Schmutzler, Robert. Art Nouveau. Harry N. Abrams, 1962.

Thomas, J. W. Tannhäuser, Poet and Legend. University of North Carolina Press, 1974.

Wagner, Richard. Mein Leben. Edited by Martin Gregor Delin, Paul List, 1963

Wagner, Richard. My Life: Mein Leben. Translated by Andrew Gray, Edited by Mary Whittall, Cambridge University Press, 1983.

Wagner, Richard. Tannhauser. Translated by Thomas W. Rolleston, Illustrated by Willy Pogany. G.G. Harrap and Co, 1911.

KA/Fall2016