Castle of Frankenstein (1962-1975)

“If we say ‘art’ is any piece of creative work

from which an audience receives more than it gives …

then I believe that the artistic value the horror movie

most frequently offers is its ability to form a liaison

between our fantasy fears and our real fears.”

- Stephen King, Danse Macabre, p. 131

Welcome

to the...

Castle of Frankenstein!

While reading Stephen King’s Danse Macabre for inspiration for this project, I ecstatically stumbled upon multiple mentions of Castle of Frankenstein (CoF). King compliments CoF for its “fairly sophisticated reviewing[,]” saying that it was “the best of the ‘monster mags’ and one that died much too soon” (142). There are traces of CoF throughout the internet – in fan blogs and on collector websites – but recognition from one of horror’s most recognized authors is perhaps the most monumental evidence I found when trying to gauge CoF's legacy. It truly speaks to the imprint CoF made on the world of horror and on horror fans.

For these reasons, this project will focus primarily on CoF's contribution to, and place in, the world of horror.

Although CoF also paid significant attention to science fiction and fantasy, as well as the comic book industry,

CoF is most interesting to me as a publication which promoted passionately the allure and adoration of horror.

The University of Victoria’s collection begins with issue 6, in 1964. It also contains issues 8, 9, 20, 21,

22, 23, 24, and 25. Issue 25 was Castle of Frankenstein’s last in 1975.

These particular issues are this page's guide in witnessing how Castle of Frankenstein represented horror culture

in the 1960s and 1970s, adapted as a film genre magazine to stay alive alongside a changing film

industry, and inevitably found its place in horror's history.

Defining Castle of Frankenstein

An array of terminology classifies Castle of Frankenstein: magazine, journal, fanzine, fan magazine, film magazine, filmzine, etc. In Stephen King’s Danse Macabre, King calls Castle of Frankenstein a “journal” (196). However, Castle of Frankenstein takes many of its features and much of its style from fanzines. And yet, in its most simple form Castle of Frankenstein is, perhaps, a magazine.

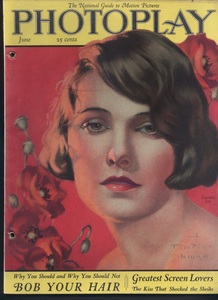

It is arguably most easy to rule out CoF’s classification as a fan magazine. Although CoF is dedicated to its readership—the fans of films—and, according to Anthony Slide, author of Inside the Hollywood Fan Magazine: A History of Star Makers, Fabricators, and Gossip Mongers, “a fan magazine [is] fundamentally a film- and entertainment-related periodical aimed at a general fan[,]” (11) there are some elements that eliminate it from this category. For one, fan magazines were aimed at “an average member of the moviegoing public who more often than not was female” (Slide 11; my emphasis). Anthony Slide also notes that although “film buffs might be the primary purchasers of old fan magazines today, they were not originally targeted as the primary audience” (11). CoF, as I will later argue, is predominantly concerned with those fans we would label as "film buffs"—the "intellectual" fan who sought details and analysis (although these elements could sometimes be found in fan magazines as well). In the 60s and 70s, fan magazines often focused on the human interest side of film; they wanted to convey to the reader the social lives of actors and actresses—content they were often criticised for—similarly to the modern day gossip magazine (Slide 184). This criticism predominately manifested when editors would manipulate titles to imply “more scurrilous content” than the actual story told (Slide 185). Below are images of Photoplay, one of America's first fan magazines for film which ran from 1911-1980, and another holding in the University of Victoria's Special Collections. The captions below each image explain how Photoplay exemplifies a fan magazine. Over the course of this page, it will become obvious how CoF differs from these characteristics.

Cover of Photoplay (Vol. 6, No. 1) featuring prominent silent film actress Leatrice Joy. Almost all of Photoplay's covers featured young female actresses.

An example of a table of contents from Photoplay. Note the emphasis, again, on female stars, femininity, beauty, and romance.

Image from the advertising section of Photoplay which highlights a girdle that slims one’s waist while wearing a bathing suit. Advertising in Photoplay was predominately directed at a female audience.

An article detailing the fitness habits of actors and actresses. This article tries to communicate how glamourous Hollywood life is by highlighting the elite Hollywood Athletic Club, but it simultaneously tries to humanize actors and actresses with their commitment to physical fitness in order to maintain the interest of the average American citizen. This is reminiscent of the reoccurring feature in modern day US Weekly: Stars—They’re Just Like Us!

“For me, the impact of fanzines was reminiscent of an old legend.

At the time of Erasmus of Rotterdam a little goblin replaced one night

all the solemn churchbells of the city with tinkling sleigh bells.

The citizens were awakened in the morning by the jingling sound

instead of the stern clamor of the usual bells. They took it as a special

message of cheer and optimism. Having had to read so many solemn

professional and professorial publications in my life, the unconventional

fanzines reminded me of the cheery sleigh bells of Rotterdam.”

- Fredric Wertham, The World of Fanzines, p. 36

Fanzines

Where CoF fits best is perhaps under the classification of fanzine. In fact, one of CoF’s editors and designers, Bhob Stewart, calls CoF a “zine” in an interview he did in the late 70s on Flickhead (a now defunct website featuring the writings of web critic, Raymond Young).

Fredric Wertham, in The World of Fanzines, defines fanzines as “uncommercial, nonprofessional, small-circulation magazines which their editors produce, publish, and distribute” (33). CoF was published by Gothic Castle Publishing, a creation of CoF’s editor and inventor, Calvin T. Beck. It’s mentioned in Calvin T. Beck’s interview with Flickhead that CoF was originally distributed through Kable News; although it’s unclear if the magazine stayed with them throughout the entirety of their run, CoF also seemingly ended under Kable News' umbrella. When reading letters to the editor in CoF, we can see that the magazine was distributed all over North America, including Canada. However, CoF’s distribution was irregular and scattered at best. This reflects Wertham's note that fanzines “are not commercially oriented [and] may come out irregularly” (33).

Wertham explains the importance of small circulation in the classification of the fanzine genre: “[i]n contrast to mass media and mass circulation publications—which of course have their place in our society—fanzines are intended for small audiences. We have built up an enormous communication machinery which at times confronts us like a superior power and, paradoxically, contributes to our isolation. The individual is apt to be submerged and regarded as a statistic. There is no such tendency in fanzines” (35). CoF relied on its readers to build its community, and its community was limited to fans of horror (as well as sci-fi and fantasy) who appreciated the genre in various mediums, not just film (although that was the predominant focus). Readers of CoF played an active role in its success and even, as we will see later, its content.

This readership community is best illustrated through the letters to the editor that appear in CoF, which are vital to fulfilling CoF's classification as a fanzine: “Letters to the editor are one of the most important and distinctive components of fanzines. They embody the principle: ‘Our words are to people from people’ … Readers write the editor, they engage in discussion with other letter writers, editors write to each other. Whereas in the commercial press editors and publishers feel that they confer a privilege—which they often withhold—on anyone by printing his letter” (Wertham 97). There is also the unique characteristic of fanzines in that "the editor sometimes inserts his [or her] own comments, humorous or critical, in brackets in the text of the letter" (Wertham 98). See especially Figs. 31 and 32.

CoF also mirrors the standard contents of a fanzine: “fiction, interviews, letters, cartoons, strips, etc. The different departments are not necessarily strictly divided and there is no set pattern for their arrangement in an issue. Nor do all the various features appear in every fanzine” (Wertham 92). Wertham continues to note how none of these features are exclusive to fanzines—they are in many popular, mass-produced publications—but the way they are presented and their frequency (or lack thereof) develops its own individuality under fanzines (92).

Who was Castle of Frankenstein?

First and foremost, CoF was Calvin T. Beck. Beck formed CoF after his attempt to launch a journal titled Journal of Frankenstein failed. Bhob Stewart, who would grow to be an important piece of the CoF puzzle, noted in an interview on Flickhead that “[b]ack in 1961 and ‘62, when the first two issues of the Castle of Frankenstein were assembled, the true staff consisted of only two people—Ken Beale, who worked on copy, and Larry Ivie, who handled layouts”. However, in the same Flickhead interview, Bhob Stewart explains how in 1962 he received a call asking for his assistance to finish the layout for issue 3, a request which he answered:

After what seemed an interminable length of time exchanging pleasantries upstairs, Ken, Cal and I descended the stairs to the basement [of Cal's house] to begin work. I was astounded to discover that the layout work area was equipped with almost no professional tools. Instead there were things like grammar school protractors and Woolworth brushes …

Since I hadn’t expected to get credit, I was startled to see that Cal had me down as ‘art editor’ in the printed mag. To me, it looked pretty wretched and hastily done. Therefore I began work on the next issue simply because, with my name on the masthead, it seemed necessary for me to produce something that didn’t look second rate.

Stewart’s description emphasises the humble beginnings of CoF, which are explicitly reminiscent of the homemade efforts made by most fanzine editors/publishers. Stewart would work on CoF periodically throughout its lifespan with varying writing credits. In the interview conducted by Raymond Young, Stewart notes that by issue 6, the first issue in UVic's collection, CoF had “a few writers with critical sensibilities, and Cal and [Stewart] [had] developed an interesting collaborative system”.

There were other notable contributors to CoF—notable in name. Robert Michael Cotter’s book, The Great Monster Magazines, notes how CoF “had an ‘A’ list of contributors, many of whom would go on to become leading lights in the field of horror film scholarship, like William Everson (Classics of the Horror Film, More Classics of the Horror Film), Ken Beale [mentioned above] and Richard Bojarski (The Films of Boris Karloff), Chris Steinbrunner, and Jim Harmon. Also appearing were Larry Hama before he became a comic book artist, and even Joe Dante before he became a director” (59).

SETTING

The context of the film industry and film culture at

the birth of Castle of Frankenstein in the 1960s.

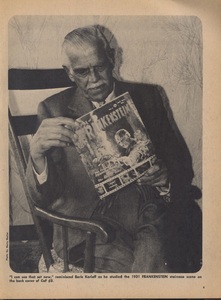

Fig. 5: Boris Karloff, iconic horror actor, reading Castle of Frankenstein; Karloff is best known for playing Frankenstein's monster in Frankenstein (1931)—a film which inspired many of the monster movies which followed.

Castle of Frankenstein offers fans and scholars of the horror genre a window into a specific era of horror and a front row seat to watch the unravelling of the new direction it would follow. To understand the content in CoF, we must first understand where it was situated not just on the timeline of horror, but on the timeline of film culture and production.

The 1960s were a particularly turbulent time for the film industry; it was a time of change, and there was a fervent need for all of those involved in the medium to adapt. As Paul Monaco notes in History of American Cinema: The Sixties: “A studio such as Paramount, for example, which once had produced more than a hundred films per year, averaged just fifteen features annually during the 1960s” (10). This was largely due to the fact that, as stated by Kendall R. Phillips in Projected Fears: Horror Films and American Culture, in 1948, the “Supreme Court ruled that the [five biggest studios—MGM, Paramount, Twentieth Century Fox, RKO, and Warner Brothers—] would have to sell off their theatre chains” which meant that “as these major studios [were] no longer assured of profitable theatre space, [they] focused on making fewer and ‘bigger’ pictures” (91).

Another significant change, which required adaptation from the industry, was how in 1959, 86 percent of American homes had a television (Monaco 16). Production companies were concerned that this advancement in home entertainment would “undermine” the “social habit of regular family excursions to the movies” (Monaco 16); however, although “[t]elevision had taken away much of the mass audience from movies in the 1950s, [it] become increasingly dependent on the motion picture industry’s product and its production values for much of its prime-time programming by the end of the 1960s” (Monaco 17). Monaco acknowledges, however, that although movie theatre attendance began to drop before the popularity of TV, television was still a cause of low theatre attendance (40). For example, “[w]here television first became available movie attendance declined most quickly [and] [w]henever an additional broadcast channel was added in any market, the decline in movie theatre attendance accelerated immediately and spread the most rapidly” (Monaco 40). As Mondaco argues, due to fewer people attending movies, Hollywood dropped the double-bill from theatres and focused on one major film—this meant that companies produced fewer movies and possible failure of the films brought greater repercussions (Monaco 10).

The change in the number of films being produced, however, opened the door for independent films to prosper, which in turn opened the door for a new breed of horror films; these filmmakers “push[ed] lower-quality, though more daring, films into American theatres" (Phillips 91). For example, the George A. Romeo film, Night of the Living Dead (1968), had a mere $114,000 budget—the production “group chose horror because of its potential for profitability” (Phillips 82).

Another positive for horror that arose instead from the changing social culture of the 1960s was how “[b]y the end of the [1960s], industry pundits claimed that features aimed at the ‘family’ market could no longer attract the adolescents and young adults who had become the mainstay of the movie theatre box office” (Monaco 44). The need to market to younger audiences made horror, with its unique violence, gore, and commentary on human nature, all the more appealing for the film industry to produce. In fact, “[a]s early as 1961, Variety had begun publishing obituaries for the Hollywood happy ending: ‘The sicko ones are making for box office health more readily than the happier movies’” (Monaco 44).

This was the breeding ground for an alternative genre like horror, and a magazine like Castle of Frankenstein, to flourish. In the 1960s, Psycho (1960) firmly gave horror its chance at rebirth: “As the French New Wave director Francois Truffaut remarked, Psycho ‘was oriented toward a new generation of filmgoers’ and was premised on an aesthetic that was fundamentally new. Psycho has been called ‘the movie that cut movie history in half’[;] The precise moment at which that division occurs is in the famed motel shower scene when Janet Leigh’s character, Marion Crane, is stabbed to death” (Monaco 189).

Two years after the release of Psycho, Castle of Frankenstein produced its first issue.

MARKETING

What did advertising in Castle of Frankenstein look like?

How did advertising promote horror culture to attract

readers (the horror fan base)?

How did Castle of Frankenstein, through its advertising and features,

contribute to the community of horror and fanzines?

Fig. 8: Promotional advertisement for French horror

magazine Midi-Minuit Fantastique.

Fig. 9: The CoFanaddicts Gallery,

featuring Vincent Van Ghool,

the Gallery Ghoul.

Fig. 10: A feature within CoF which suggested other publications which may be of interest to CoF readers.

Castle of Frankenstein did not give space to outside advertisements—a common characteristic of fanzines (Wertham 80). As advertising is a significant way for publications to earn profit, it’s unclear where the majority of the funds to produce the magazine came from. It is fair to assume that some profit came from subscriptions and the purchasing of back issues, but much of it likely came from the production team and Beck. In his interview with Flickhead, Stewart complained of CoF's lack of profit in relation to his struggles to assemble content:

I was expected to put together a magazine, without spending anything, by assembling existing material. Naturally, this made it difficult to solicit from writers and artists, since I couldn’t guarantee anyone what or when they might be paid, or even if they would be paid. This explains why the magazine used photo covers during the time I was editor—no one had to be paid.

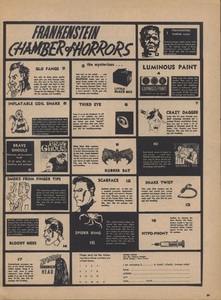

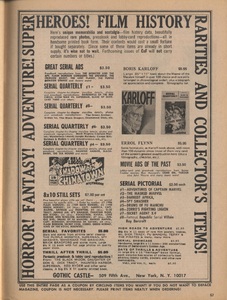

However, in CoF there were advertisements for products that went through Castle Publishing. Fig. 12 and 13 in the gallery below show how CoF sold horror related props and toys, ranging from 75¢ to $4.98, as well as memorabilia and collectibles, ranging from $3.50 to $7.00. This money went directly to Gothic Castle, as the mailing information shows us, although it’s unclear if the money was further distributed to whoever supplied the products. Regardless, it’s fair to assume that CoF made some money off this business venture. These ads appear, in some shape or form, in each issue (at least those in UVic's Special Collections).

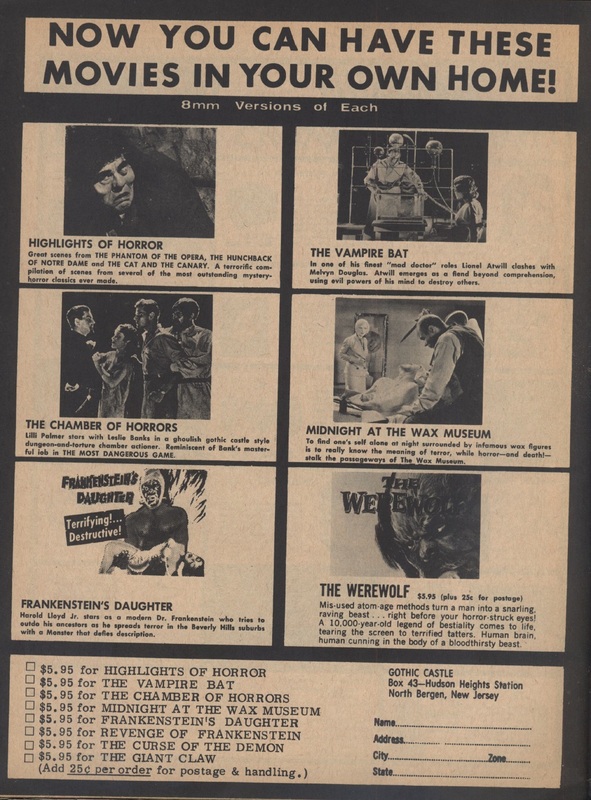

Readers of CoF could also purchase 8mm films (See Fig. 11 below). The purchasing of the films again went through Gothic Castle, marked at $5.95 each, although it's safe to assume Gothic Castle was not producing 8mm films—they were likely brought in from outside sources, and it's unknown if this procured any profit for CoF. CoF's interest in selling 8mm films could arguably have been not only out of recognition of their readers who are ardent film buffs and collectors, but their recognition of the fact that more and more people were watching films in their homes. It's a recognition of how, to stay alive and relevant, CoF sought to appeal to all modes of film viewing.

CoF also posted advertisements for collectables through their CoFanaddicts Gallery. This was a free service where fans—no professionals—could write to CoF with wanted and sale ads. Such ads would be accompanied by the reader’s mailing address so that other readers could seek them out directly. The service also allowed readers with similar interests to communicate with each other simply for correspondence purposes as well. The CoFanaddicts Gallery was a monumental factor in maintaining CoF's sense of community.

Before it was the CoFanaddicts Gallery, however, this section featured at the end of the section for the letters to the editor, and shared space with advertisements and acknowledgements of other fanzines and magazines. Eventually, this idea of suggesting to readers other publications which may align with their interests (and feature content similar to that of CoF's) would grow to be its own feature as well (See Fig. 10). The acknowledgment of other fanzines is another element which positions CoF as a fanzine. Wertham explains that it was common for “fanzines [to] review other fanzines” as “fanzines have a quality which makes them a special phenomenon in our communication setup” (111, 112). Fanzines “are critical but not destructive. Instead of belittling one another they try to further each other’s interest. They often give what they call a ‘plug’ to other fanzines … [Overall,] they represent an attitude which is healthy and decent” (Wertham 112).

What's important to note about the aforementioned content is CoF's commitment to focusing on horror-related items. Their advertising content was focused on their reader being a fan of a particular thing—in this case, horror. It did not assume or cater to a reader's gender, age, or other identifiers. The content, no matter the medium, was targeted towards fans of horror. This will be touched on again in the Audience section.

Various advertisements with

products that readers

could purchase through

Gothic Castle Publishing Co.

Other ways CoF promoted

horror culture...

CoF also gave, albeit irregular, attention to radio, literature, and comics. The magazine predominately did this through advertisements, feature articles, and reviews. Lin Carter periodically wrote book reviews for CoF. Fig. 14 shows Carter's article where he highlighted and reviewed "noteworthy" novels released in 1965. Adjacent to this image, in Fig. 15, is CoF's feature on radio drama—"On the Air"—which focused on radio shows from the sci-fi, fantasy, mystery, and horror genres. Articles such as "On the Air" took on nostalgic tones, arguably appealing to older fans looking to reflect, but it also offered insight for younger generations who were not privy to such fond memories of radio. These articles were symbolic of CoF's conscious effort to appeal to fans with interests beyond film. It is also possible that CoF not only wanted to pay tribute to the earlier mediums which bred the films many had grown to love, but they wanted to offer a history of genre as well as an interesting commentary.

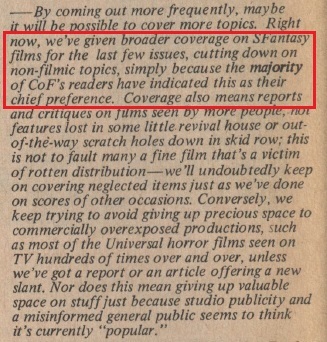

Being, however, that CoF was predominately a film magazine, it did not give more than a few pages to a feature focusing on media other than film. Fig. 16 shows an excerpt of a reply made by Calvin T. Beck to a reader, Gary Kimber, who was concerned that CoF wasn't giving enough attention to content outside film, and that their film content was nearing on repetitive (52). Beck insists in the excerpt that CoF's commitment to film stems not just from the editor's and contributor's interests, but from the preferences of readers. One particular concern of the reader was comic book reviews, to which Beck argued later in his reply that "while there are probably 175 thousand comics fans and collectors ... there are probably at least fifteen million SFantasy film fans—and that's not even counting general audiences and those watching TV who are marginally addicted" (52). This was Beck's justification for deciding which subjects CoF's time and energy would be spent on.

Note: The term "SFantasy" used by Beck in his

reply is an all-encompassing term for all the

genres in CoF: sci-fi, fantasy, and horror.

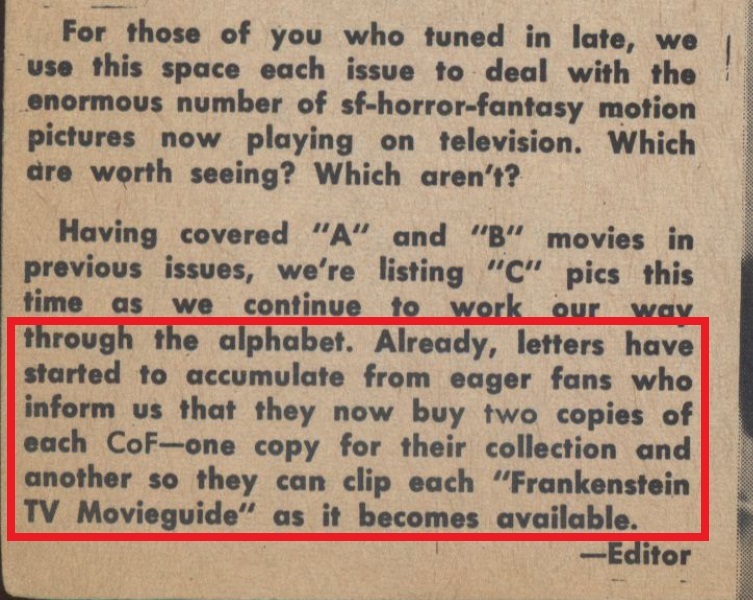

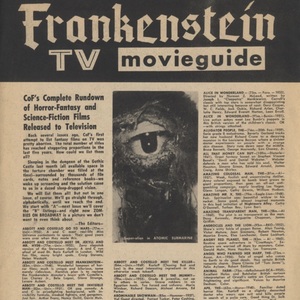

In the above section, Beck notes that film fans were extending their viewing of films to TV as well. CoF’s acknowledgement of this, however, went beyond a continued commitment to primarily focus on film in CoF—they also invented a reoccurring article titled the Frankenstein TV Movie Guide.

This movie guide began in issue 6, although haphazard versions of it existed before. The goal of this guide was to provide a comprehensive list of not only horror films on TV, but science fiction and fantasy. The methodology of such an endeavour was that CoF would list all the films that appeared on TV in alphabetical order—starting with “A”, and focusing on one or two letters per each issue that followed. This idea was born out of Bhob Stewart’s desire to do something with the exorbitant amount of images collected by Beck. Stewart explains this further in his interview with Flickhead:

I had familiarized myself with most of the pictures in Cal’s ever-growing files. [It] struck me that many of these pictures might never see print. Around this time a new director had taken over the Museum of Modern Art’s film collection, instigating a policy of showing every film in the MOMA collection alphabetically. Inspired by this, and dissatisfied with the unorganized film listings in early CoF's, the CoF Movieguide was born, beginning in 6. It was all just a scheme to print the best stills from Cal’s files!

Although CoF doesn't outright acknowledge a desire to adapt to the growing television industry, they were perhaps unconsciously reacting to their environment. As Monaco notes:

More thorough research from the late 1980s and the early 1990s into the history of investment in production for television by the Hollywood major … has documented that Hollywood was very much active in entering production for [the] medium [of television] … [E]xecutives wanted to exploit the medium to play movies that had been produced for theatrical release dating back well before the advent of commercial television. (16)

And this endeavour of CoF’s was extremely well received. As noted in Fig. 17, readers soon started buying multiple copies of CoF so that they could keep one copy for collecting purposes, and have another to tear out the movie guide from. The Frankenstein TV Movieguide also helped fuel the community surrounding CoF. Readers would frequently write to CoF to contribute to the list or mention films that the editors had missed. Therefore, the movie guide was not only engaging with the changing climate of the film industry, and thus keeping CoF alive with readers buying multiple copies, but it was also contributing to horror culture and its relevancy and growth. Arguably, such a guide was best received by the 'film buff' horror fan of CoF, as such cataloguing exemplified their affection for a meticulously detailed pursuit of knowledge about horror film.

CINEMATOGRAPHY

The imagination behind Castle of Frankenstein

Fig. 20: Description of the "Gothic Castle" dungeon.

Fig. 21: Igor Hyde... before the spelling of his name was corrected in the next issue to Ygor.

Fig. 22: Ygor Hyde

Fig. 23: Vincent Van Ghool

welcoming readers to the

CoFanaddicts Gallery.

Outside of marketing, another way that CoF engaged with their readership is through the creation of a "Gothic Castle"—or “Castle of Frankenstein”. Within its pages, CoF built its own narrative that would interact with the reader. The characters they invented within said narrative helped maintain CoF alongside the editors, like employees. While also being an example of humour this narrative is, most importantly, read as a vision of horror. For example, in Fig. 20, which is taken from the explanation given for the invention of the TV Movieguide in issue 6, the editors indicate that they are working in the dungeon of the Gothic Castle; growing the horror theme, they also reference a torture chamber and use language such as “screaming” and “dazed sleep-drugged vision”.

Vincent van Ghool (Fig. 23), the ghoul who presided over CoF’s CoFanaddicts Gallery, is one of CoF's reoccurring characters. Although the CoFanaddicts Gallery's first appears—as per UVic's holdings—is in issue 9, Vincent does not appear in UVic's issues of CoF until issue 20. However, there is evidence of him in an earlier issue: issue 15—interestingly, Beck's signature is attributed to the sketch of Vincent. There is an even earlier sighting of him in issue 3, although he does not yet seemingly have a name. It would clearly take a while for the character of Vincent van Ghool to form. Eventually though, as a resident of the Castle of Frankenstein, Vincent could also be found in the mausoleum or interacting with other characters, such as Ygor. The two would supposedly go on adventures, have secret meetings, and host parties. Ygor appears randomly throughout CoF, but there were two examples (as seen in Fig. 21 and 22) where he came before the table of contents to welcome readers, indicating that he is their host on their journey through the 'castle' (or contents of each issue); he is also the keeper of the Gothic Castle. This journey further paints CoF as an interactive, almost ‘choose-your-own-adventure' style publication, which helps create and maintain a relationship between CoF and their readers. In addition to interacting with readers, Ygor also interacts with the editors. As illustrated in Fig, 23, he shames the editors for spelling his name wrong. Ygor acknowledges that the magazine is sometimes victim to bad editing and typos.

Note: Links to some digital images of CoF issues which

are not in UVic's Special Collections can be found at the

bottom of this page under Genre.

SCRIPT

"The Thrill of the Scare":

What is it about horror films?

And why would people want to read about them?

“The good horror tale will dance its way to the center of your life and find the secret door to the room you believed no one but you knew of—as both Albert Camus and Billy Joel have pointed out,

The Stranger makes us nervous . . .

but we love to try on his face in secret”

- Stephen King, Danse Macabre, pp. 18

(Emphasis added)

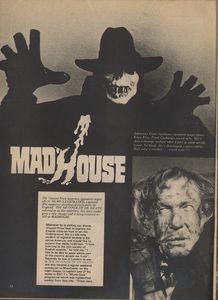

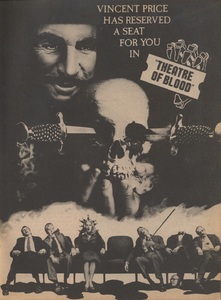

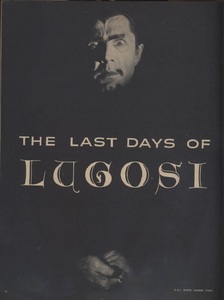

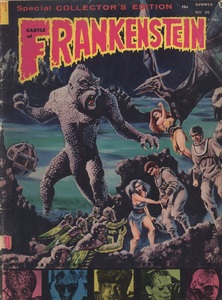

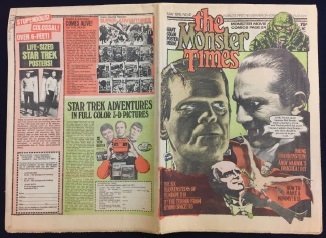

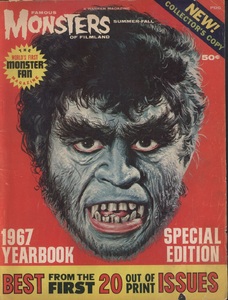

Stephen King, as noted at the beginning of this exhibit, labelled Castle of Frankenstein a "monster mag" (142). This designation applied to a few magazines in the twentieth century, such as Famous Monsters of Filmland, The Monster Times, and Fangoria—a magazine which began its publication in 1979 and continues to the present day. Although there seemingly exists no official definition of a "monster mag", these magazines are characteristically focused on the idea of the "monster," which can take many forms. For example, a monster may be the blood-sucking vampire Dracula, the distorted face of Professor Nolter (as seen in Fig. 24) in The Mutations (1974), the members of the cannibalistic family in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, or the Pale Man from Guillermo Del Toro's Pan's Labyrinth (2006). These monsters are labelled as such for their appearance, actions, or both.

The monster is what gives CoF not only its content, but its allure. As Noel Carroll, in "Why horror?", states:

Monsters … are repelling because they violate standing categories. But for the self-same reason, they are also compelling of our attention. They are attractive, in the sense that they elicit interest, and they are the cause of, for many, irresistible attention, again, just because they violate standing categories. They are curiosities. They can rivet attention and thrill for the self-same reason that they disturb, distress, and disgust. (39)

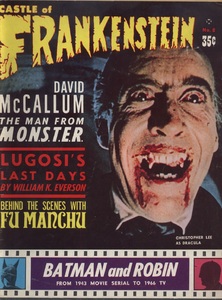

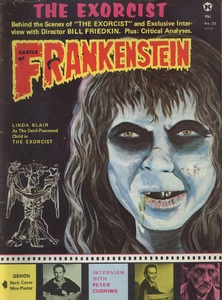

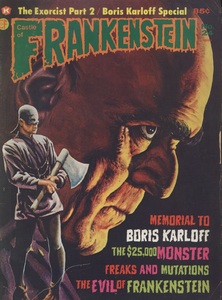

This attractiveness is what draws readers to the majority of the subject matter in CoF, and it's something CoF is aware of. In Fig. 25 it is noted how CoF consciously chooses to put the villains on the front cover. Although this remark was made in regards to CoF's Batman issue, time and time again CoF flaunts the villain on their front cover. Examples of this can be seen in the gallery below. This illustrates how CoF believes, or perhaps knows, that there is such attractiveness to the villain that they are able to sell magazines by spotlighting the villain's image. In addition to featuring the villain on the covers of their issues, CoF also designates much of their inside content to highlighting details about villains, monsters, and the "bad guys" of horror films. However paradoxical it is, CoF finds much of its success in their audience's love of villainy or evil.

AUDIENCE

Who was reading Castle of Frankenstein?

Fig. 26: Letter from Jerry Tillotson.

Fig. 27

Fig. 28: Letter from Steve and Erwin Vertlieb.

Fig. 29: Letter from Thomas Scofield.

Bhob Stewart’s Flickhead interview explains the vision he had for the intended audience of CoF:

Jim Warren gave a magazine interview in which he stated flatly that his Famous Monsters of Filmland [CoF’s main competitor] was cleverly calculated to hit a nine- to twelve-year-old market. When I read this I quite consciously began slanting CoF toward a nine- to sixty-five-year-old market on the theory there are more people!

Stewart’s idea of CoF’s readership being nonspecific is for good reason—he wanted CoF to be accessible to all readers regardless of age. Furthermore, there is the assumption that Stewart (and Beck) didn’t want to limit CoF’s readership to specific genders or economic classes. However, CoF did have limitations which changed their demographic, as Calvin Beck notes when he speaks of Stewart’s contributions to CoF in his Flickhead interview:

Bhob Stewart was ahead of his time in many literary and graphic areas, but his approach tended to be more esoteric than practical. He gravitated toward underground comics and newspapers, and other limited circulation publications that were popular in large cities but not in the middle America hinterlands and boondocks where most of CoF was sold. Our intellectual tastes were therefore hyped up on some occasions, while my commercial sense would evaporate, and we’d see the result in lower sales.

Although CoF did not purposely limit their audience, the fact that its distribution was more likely to reach areas with smaller, perhaps more rural, populations meant that CoF was limited to a specific readership, which arguably effected which economic classes were reading CoF even if the content within CoF was not purposely imposing these limitations. Overall though, if fans could access CoF, they could engage with it no matter their background.

What’s important, however, is that CoF was still targeted towards fans of specific genres. And horror, specifically, often breeds a certain type of fan, and within this group of fans, there is a supposed hierarchy. Mark Kermode argues that:

The horror fan … is … not only able but positively compelled to "read" rather than merely "watch" such movies. The novice, however, sees only the dismembered bodies, hears only the screams and groans, reacts only with revulsion or contempt. Being unable to differentiate between the real and the surreal, they consistently misinterpret horror fans’ interaction with texts that mean nothing to them. (qtd. in Hills 74)

Mark Voger, in his book Monster Mash: The Creepy Kooky Monster Craze in America, 1957-1972, states that CoF “played to an aficionado sensibility” (138). This style often catered to the "intellectual" film buff—those fans who consider themselves "true" horror fans—as illustrated above by Kermode. Evidence of this is seen in Fig. 28 in a letter from Steve and Erwin Verlieb. They compliment CoF for knowing the difference between good and bad horror productions, and for representing the belief that true horror is art. They even go as far to say that CoF is their “bible.” Therefore, Stewart wasn’t necessarily wrong to appeal to the intellectual sides of their readers with his “intellectual tastes,” despite the fact that Beck claimed it resulted in lower sales. Bhob Stewart mentioned in his interview with Flickhead that CoF was seen as an inspiration because of its serious and knowledgeable tone:

I have occasionally met young filmmakers, artists and writers who grew up on CoF. Apparently, as well as I can ascertain, the zine picked up many first-time readers with 11. I get a great satisfaction out of hearing how these people were ‘educated’ by CoF when they were in their early teens … These young people who are former CoF readers who are now involved in various creative pursuits make me feel I succeeded in getting this point across.

Stewart correctly touches on not only the creative value of CoF, but the educational value. This educational value was also noted by reader Jerry Tillotson, as shown in Fig. 26, who explains how CoF had found its way into academic circles. This is, arguably, reflective of how Kendall R. Phillips states: “[by the mid-1960s,] [b]eginning in France and slowly spreading to America, films were increasingly embraced as their own form of literature” (92). If film could be interpreted as literature, it was necessary for literature about film to become commonplace, and perhaps even popularized and mainstream—even literature which presented itself within the pop culture market. Phillips acknowledges that “[p]rior to the 1950s and 1960s, films were largely conceived as low culture, but on both sides of the Atlantic, individuals were beginning to champion the medium of film” (92). Arguably, horror was considered even more "low brow" than other genres, so it was vital to horror's success to have bridges which connected horror to academia and other standards of acceptability. CoF, and its readers, helped build this bridge.

There is, however, a danger to the hierarchy of horror fans, as Matt Hills notes in The Pleasure of Horror, in response to Mark Kermode: the “discursive problem” with the “Romantic-intensity-turned-to-cool-knowledgeability” origin story of most horror fans “is that while knowledge and ‘literacy’ can be used to distinguish and revalue the adult, ‘tortured’ horror fan—the reader of horror’s niche magazines and participant in fan cultural activities—such discourses cannot logically or readily account for why horror so affected or inspired the proto-fan in the first place” (77). It is hard to account for why horror inspires the “proto-fan”, although a conclusion could be drawn from the earlier conversation about the appeal of the villain. What is important, however, is how CoF fostered an environment where the “proto-fan” could exist beside the 'true' horror fan. CoF primarily provides materials for the film buff—TV Movieguide, in-depth articles with directors and actors, features on specialists in production teams (such as that which is shown in Fig. 27)—but they also present material for the “proto-fan” who is looking for a gateway into the world of horror, such as nine year old Thomas, who wrote to CoF to express his affection for a particular reoccurring feature (Fig. 29). Arguably, even fans who read CoF for the science fiction or fantasy content would be exposed to their horror content as well, or hybrids of the genres such as horror-science fiction, and could therefore be fans in the making, waiting for the right window of opportunity into the world of horror.

Calvin Beck was not entirely against the romanticism of being a ‘true’ horror fan either. In his Flickhead interview, he argued:

I think that all film categories and genres should be studied. I’d evince a predilection for the b’s and z’s because this is where one finds the filmmaking DNA code. Because of their limited capital, the b’s and z’s involve a certain self-discipline and structure that is, more often than not, sincere and direct. I feel that an interesting and successful a-film may only be a b-film on a bigger budget.

Note: The "b's" and "z's" Beck speaks of are

B-Films and Z-Films—films which are low-budget;

allegedly, the lower you go down the alphabet,

the "lower" the quality of film.

The attitude which believes in the value of b- and z-films mirrors Stephen King’s romantic notion of genuine horror fans:

If you’re a genuine horror fan, you develop the same sort of sophistication that a follower of the ballet develops; you get a feeling for the depth and texture of the genre. Your ear develops with your eye, and the sound of quality always comes through to the keen ear. There is fine Waterford crystal, which rings delicately when struck, no matter how thick and chunky it may look; and then there are the Flintstone jelly glasses. You can drink your Dom Perignon out of either one, but friends, there is a difference. (142)

Let's do the time warp

Curious about what an avid film buff, horror fanatic, and/or reader of CoF would actually look like?

Travel back to the 1960s and find out!

In its early days, Castle of Frankenstein would post photos of their readers alongside their letters.

Examples from issue 2 can be seen here, here, and here.

Distribution and readership

As noted above on numerous occasions, CoF often had problems with distribution. This problem was also noted in other sources. For example, Cotter's study complains that “the most maddening thing about CoF[,] even if you were an ardent fan, [was that] you never knew when the next issue was coming out[,] [which] was mostly due to the caprices and finances of its editor, Calvin T. Beck” (59). Voger expresses a similar sentiment: “A downside [of CoF] was [their] erratic publishing schedule” (138).

Aside from the financial problems CoF frequently faced, Beck offered further insight, in his interview with Flickhead, into CoF’s irregular releases:

Magazine publishing is, by its very nature, a commercial, not artistic, business. Although I’ve some insight in marketing, I’ve never been a very commercial type of person. And it’s terribly difficult trying to wear two hats at one time without getting a little schizoid — that is, trying to be in business and creative simultaneously … One’s creative well being is strained trying to maintain regular schedules which conform to the establishment’s theory of productivity. This may explain why most minor magazines are infinitely superior and why most mass market mags are [s***] … In a nutshell, good wine takes time. CoF’s twenty-seven editions—including Journal of Frankenstein and the 1967 Fearbook—include some disappointing editions. But as a whole, CoF couldn’t have made a lasting impression if it had taken a purely commercial route. In the long run, it established certain principles that may have helped inspire others to do likewise or better.

CoF’s distribution problems were also noted in issues of the magazine. In issue 20, CoF addresses the problem head-on in their editorial (see Fig. 30):

Last issue we revealed some of the problems our publications had for a long time getting proper distribution in various areas around the country. Quite a large number of you reacted magnificently, it seems, and CoF is now being seen to better advantage. And we’re all quite ecstatic over this beautiful display of loyalty.

The conclusion one can draw from this is that CoF predominately relied on its readership—the people who shared their value of creative endeavor over mass marketability—to extend its distribution rather than funding from more established publishers and distributors. Beck also acknowledges in the excerpt that better distribution is not just for the sake of CoF reaching more people, but about readers having access to publications they want. Beck acknowledges a very important problem: limited access, or perhaps zero access, to certain publications or other forms of media is a form of censorship. As a member of the community of journalism, CoF is against such ideas and the dangers they impose, and they believe that their community of readers are similarly against censorship. What’s also important is that they explicitly invited their readers to “share” in the victory of battle should they succeed, and are therefore making their relationship with their readers more personal. They have extended an invitation of comradery in battle and have similarly expressed a division of the treasure should they succeed.

MISE-EN-SCÈNE/MISE-EN-PAGE

How did Castle of Frankenstein's layout cater to its readers?

Mise-en-scène, as defined by the OED, means:

"The setting, surroundings, or background of any event or action."

In regards to film, this means the visual design of the film—

the arrangement of a scene involving props, characters, setting, etc.

Mise-en-page, as defined by the OED, means:

"The design of printed pages, including the layout of text

and illustrations; (also) the composition or layout of a picture."

CoF's relationship with, and accountability to, its readers meant that they did have to please their audience, albeit while remaining true to their own vision of CoF. CoF’s relationship with their readers, beyond the conversations mentioned above, also spawned a creative collaboration which helped determine layout design.

As mentioned above, covers were an important part of CoF, and CoF had made a commitment to put villains on their covers. However, there were other aspects of the cover art that readers didn’t always agree with. For example, in Fig. 31, reader Jeff Day indicates how he favours artwork—paintings and illustrations, predominately—over photographs on the cover (for examples of covers with illustrations, see the below gallery). He also notes that he enjoys the covers when there is a fullness or crowdedness to them. This idea of crowdedness is contrasted by Ron Peterson’s letter, in Fig. 32, who states that he does not find the covers of CoF very artistic—the filmstrip is disruptive and the lettering of the title is poor and doesn’t draw the eye of onlookers. In his reply to Peterson, Beck says that “[they’ve] really been concerned about [their] layouts for a long time” (4). Beck continues, stating: “They are, perhaps, indicative of our personality: harried, hassled but ‘dedicated.’ It’s possible we’ve been so concerned—maybe too much—over the quality of written rather than visual content, we may have developed a blind spot” (4). However, Beck continues to state that the filmstrip has become a trademark detail of CoF (4). After this acknowledgment of Peterson’s concerns, Beck turns the question of cover layout to all the readers, asking them to write to CoF about “anything [they’d] like altered or

improved inside CoF” (4).

Examples

of CoF

covers

with

illustrations

or paintings

Fig. 34: An illustration featuring a simplified title of "Letters," which came after "Ghostal Mail," but before "Castle Mail Box".

Fig. 36: As seen in issue 24, CoF added a watermark to their letters section, which arguably made it harder to read the print.

Another aspect of CoF's layout which drew criticism, as reader Ron Peterson (Fig. 32) stated, was their supposedly “corny” department illustrations (illustrations which accompany the titles of the various sections of the magazine.) This sentiment was mirrored by reader Bill Warren (Fig. 39), who stated that sections such as “Ghostal Mail” and “Noosereel” were “juvenile”.

Eventually CoF would change some of their quirks to cater to their readership's criticisms and suggestions. "Ghostal Mail" (Fig. 33) eventually became "The Castle Mail Box" (Fig. 35) and "Noosereel" (Fig. 37) seemingly became "Frankenstein at Large" (Fig. 38).

However, it's possible these changes weren't as monumentally successful as they had hoped since distribution and sales did not increase and CoF ended shortly after.

FIN.

The end of Castle of Frankenstein

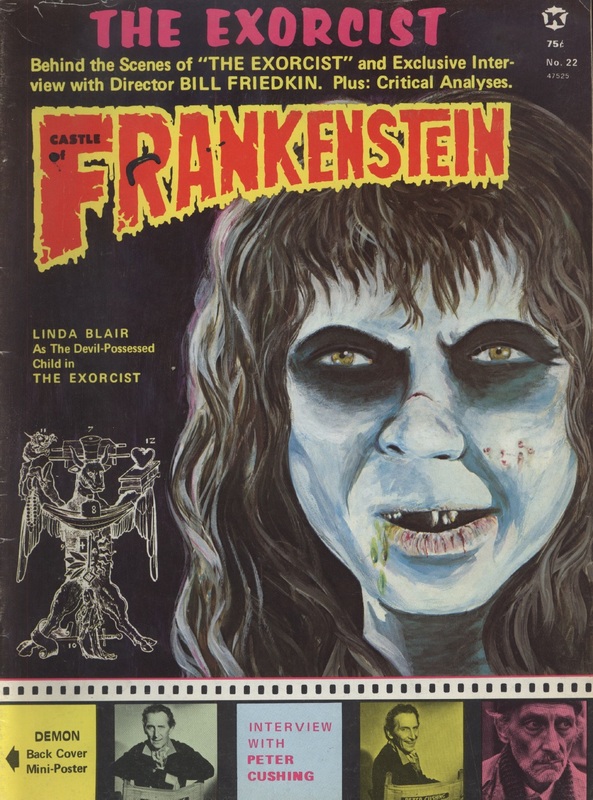

The last issue of Castle of Frankenstein was released in 1975—a year after what Phillips refers to as “the pinnacle year in the history of the American horror film[,]” as it saw the success of two iconic films: The Exorcist and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (101). CoF gave immense attention to The Exorcist over the course of two issues—issues 22 and 24, both of which are in Special Collections. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was given a three-page spread in their last issue, 25. The Exorcist, in particular, “provided an unprecedented ‘visceral visual onslaught.' The technical skill and excellent pacing of the film attracted not only enormous popularity but also unprecedented critical acclaim for a horror film” (Phillips 105). Similarly, “Texas Chainsaw took the familiar tale of the psychotic killer and simultaneously distorted and amplified it. As Carol Clover notes, Hooper’s film provided a crucial bridge between Hitchcock’s Psycho—the insane killer, the remote location, and the confusing issues of gender and sexuality—and the slasher films of the 1980s, films such as Halloween and Friday the Thirteenth” (Phillips 106).

These remarks in regards to the climate of the horror film industry indicate that CoF had an exceptional amount of material to work with as well as bright hopes for the future of horror to ride alongside. However, CoF still ended its thirteen-year run. In the closing of his interview with Raymond Young, Calvin Beck shed some light on the demise of CoF:

We began running into serious distribution problems in the mid-1970s with CoF 24, the next-to-last issue. I had a good printer named Andre Lemieux, who knew about the problems and offered to back me with his million-dollar printing establishment. We talked about launching other ventures along with CoF ...

I was also acquainted with a fine and sensitive friend at Kable News, the vice-president who heard and understood all my woes. He’d just been appointed for a short time. He was a freak in the business world: friendly, warm and intelligent. It was a liaison I’d always wanted but never could find until now. My sales shot up like magic.

But then awful, terrible things began to happen, enough to fill the plot of a James Bond movie. Amrep, the parent holding company controlling Kable, had been under federal investigation for selling allegedly worthless land in New Mexico and elsewhere … A number of Kable’s best people, including my VP friend, resigned in a matter of weeks. Mismanagement and demoralization became rife …

Tragically, my friend Andre soon died from a massive heart attack. So passed away one of the nicest people I’d ever known. And after that, everything went downhill. CoF sales dropped as quickly as they shot up. Quite frankly, I’d had enough and wasn’t about to undergo the same painful perseverance I’d endured in the 1960s. I could have shopped around for another, perhaps even healthier distribution climate, but what I’d already experienced left a bitter taste.

And thus ended

Castle of Frankenstein

However, through the issues in the University of Victoria’s Special Collections, Castle of Frankenstein lives on. These illustrate how a magazine/fanzine is an example of its circumstances, an adapting force to a changing environment, and an illustration of an unique relationship with its readership. Castle of Frankenstein has left an undeniable mark on the world of horror, and through Special Collections readers can continue to revisit its cultural and scholarly effect.

GENRE

Further reading for fans of Castle of Frankenstein, horror, and film

1) The Monster Times

Horror film fan magazine from the 1970s

UVic's Special Collections, PN1995.9 M6M652

2) Famous Monsters of Filmland

Horror/monster movie magazine

which CoF is often compared to.

UVic's Special Collections, PN1995.9 H6F3

3) Photoplay

Attributed as being one of America's first fan

magazines; used above for comparison

UVic's Special Collections, PN1993 P47

Other late twentieth century magazines in Movable Type:

1) Heresies Magazine (1977-1993)

2) Kick It Over (1982-1994)

Digital images of Castle of Frankenstein issues:

Issue 1, 2, 3, 4, 15, 17,

and Fearbook (1967) - a summary of CoF's year

Works Cited

Beck, Calvin T. Interviewed by Raymond Young. Flickhead, 2014, 21ca.com/flickhead/2_14_Beck_Interview.html.

Accessed 27 Nov. 2017.

Beck, Calvin T. Reply to Ron Peterson. Castle of Frankenstein, vol. 5, no. 4, 1973, p. 4.

Beck, Calvin T. Reply to Gary Kimber. Castle of Frankenstein, vol. 5, no. 4, 1973, p. 52.

Carroll, Noel. "Why horror?" Horror: The Film Reader, edited by Mark Jancovich, Routledge, 2002, pp. 33-45.

Castle of Frankenstein. Edited by Calvin T. Beck. Gothic Castle Publishing Co, 1964, 1966, 1973-1975. University of Victoria

Libraries Special Collections, PN1995.9 H6C3.

Cotter, Robert Michael. The Great Monster Magazines: A Critical Study of the Black and White Publications of the 1950s, 1960s

and 1970s. McFarland, 2008.

Hills, Matt. The Pleasures of Horror. Continuum, 2005.

Kimber, Gary. Letter. Castle of Frankenstein, vol. 5, no. 4, 1973, pp. 52.

King, Stephen. Danse Macabre. Everest House, 1981.

"mise-en-page, n." OED Online, Oxford University Press. Accessed 5

Feb. 2018.

"mise-en-scène, n.2." OED Online, Oxford University Press. Accessed 5

Feb. 2018.

Monaco, Paul. History of American Cinema: The Sixties. Edited by Charles Harpole, vol. 8, Charles Scribner's Sons, 2001.

Phillips, Kendall R. Projected Fears: Horror Films and American Culture. Praeger Publishers, 2005.

Photoplay. Edited by James R. Quirk. Photoplay Publishing Co., 1924. University of Victoria Libraries Special Collections,

PN1993 P47.

Slide, Anthony. Inside the Hollywood Fan Magazine: A History of Star Makers, Fabricators, and Gossip Mongers. University

Press of Mississippi, 2010.

Stewart, Bhob. Interview by Raymond Young. Flickhead, 2014, 21ca.com/flickhead/2_14_Bhob_Interview.html.

Accessed 27 November 2017.

Voger, Mark. Monster Mash: The Creepy, Kooky Monster Craze in America 1957-1972. TwoMorrows Publishing, 2015.

Waller, Gregory A. "Introduction to American Horrors (extract)." The Horror Reader, edited by Ken Gelder, Routledge, 2000, pp.

256-64.

Wertham, Fredric. The World of Fanzines. Southern Illinois University Press, 1973.

CC/Fall 2017