D.C. Beard, Jack of All Trades (1921)

The Jack of All Trades: New Ideas for American Boys

(1921)

15cm x 20cm x 4cm

LC Call Number TT160 B36

Available in

McPherson Library’s Special Collections

is this 1921 edition of Daniel Carter Beard’s

The Jack of All Trades:

New Ideas for American Boys,

published by Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Introduction

Much of this book's significance is revealed in its title:

The Jack of All Trades: New Ideas for American Boys.

It declares itself a children's text, and inherent to children's literature is an attempt to instruct and to cultivate its readers. The book's form reinforces this educational function: The Jack of All Trades is a manual that, upon its publication, aimed to teach American boys to perform or embody a certain type of “new” masculinity. Therefore, it is not only an important artifact that exemplifies early-twentieth-century ideas about masculinity, but it also provides evidence about how masculinity was actively constructed and disseminated in America during the twentieth century. Furthermore, this book shows us how the American masculinity that it promoted was raced; although

whiteness is too often considered the unraced default,

this text’s exigency stems from its ability to shed light on the ways in which

whiteness was and is constructed in response to other (also constructed) races.

This page follows a thread from this specific copy of The Jack of All Trades: New Ideas for American Boys, to its author, Daniel Carter Beard, to his association with The Boy Scouts of America, and to the racist ideologies that informed that organization at its inception. After situating the text within those networks, this page then circles back to the book itself in order to, in light of Toni Morrison’s theoretical work and Ben Jordan's historical analysis of The Boy Scouts of America, show how a conspicuous element of the text – its overwhelming emphasis on kindness to animals –attempts to implicitly define whiteness and to establish it as superior to other races.

The goal of this project

is not simply to point out the explicit and implicit racism present in The Jack of All Trades; that is not a difficult task when looking at any early-twentieth-century text. Instead, by highlighting the networks at play behind Beard's text, I hope to illuminate the ways in which the book works to construct whiteness. To provide evidence that a largely forgotten children's book from one hundred years ago was

complicit in crafting and perpetuating the narrative of whiteness and its supremacy

is a valuable undertaking; I hope this project encourages readers to do the same critical work with other texts.

(If you are interested in looking at other "forgotten children's books", click here to see another Omeka page on this topic.)

“The belief that books may be used as tools for instilling virtue in the young is an old and honored one. Since ancient times literature … has served as a medium for instructing youth in the manners and morals of society, and for introducing them to the major problems of adult life. The books young people read, therefore, often provide reflections of what society assumes to be valuable, and of the standards it holds” (Nye 60).

The Book

Bookplate inside The Jack of All Trades: New Ideas for American Boys

Back Cover of The Jack of All Trades: New Ideas for American Boys

This Special Collections item contains evidence that

it was once well loved.

In addition to a worn, stained front cover and a gouge in the fabric on the back cover, the front endpaper holds a bookplate that reads:

“This book belongs to Davenport Fithian, Jr.”

Above the bookplate, scribbled in pen, is the name

“Dan Bryant. ”

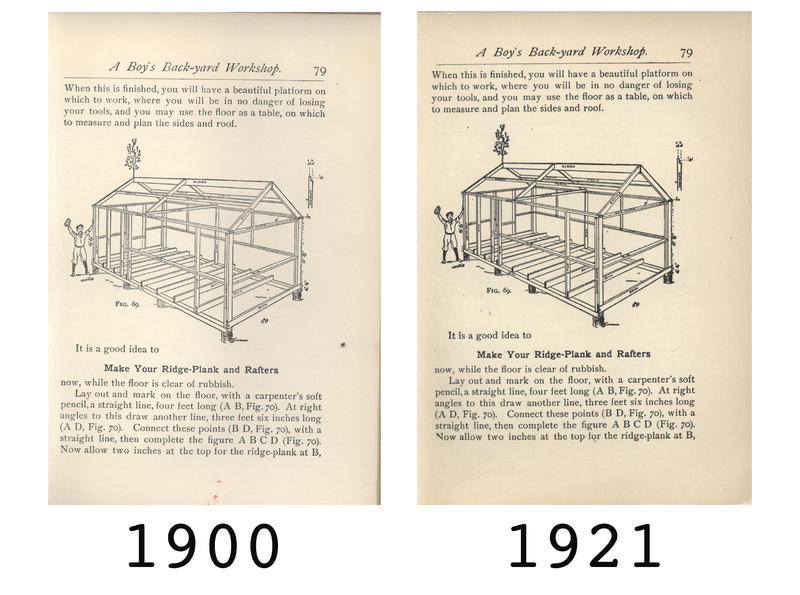

A comparison between the 1900 edition (left) and 1921 edition (right) reveals a decline in print quality after the first printing.

This comparison between the McPherson Library's 1921 edition and a 1900 (first) edition of The Jack of All Trades shows the

difference in print quality

in subsequent printings.

The later edition is comprised of lower quality paper and the print is smudged. Illustrations were printed on thicker paper than the pages with text in the 1900 edition, but the paper remains consistent throughout the 1921 edition.

This page from the 1900 edition of The Jack of All Trades shows the book's price upon its publication.

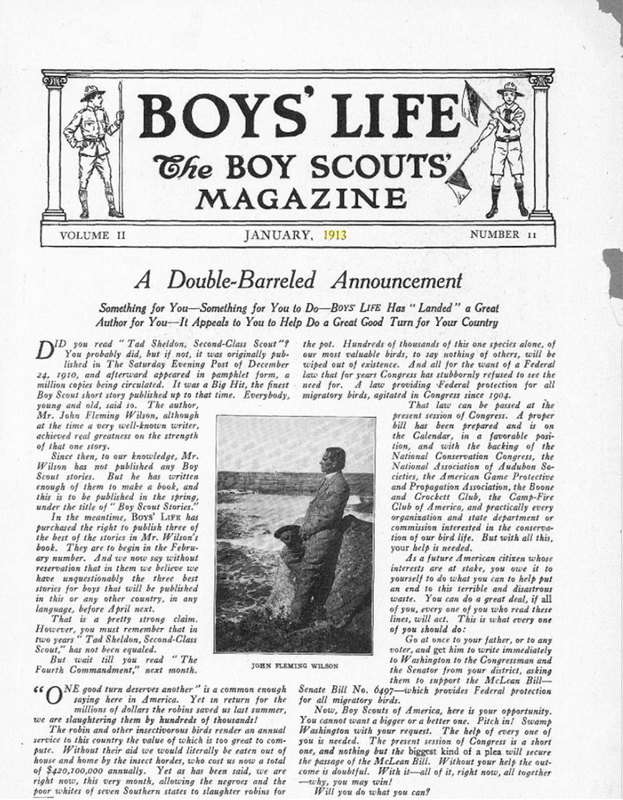

Here we see that "Boys' Life," a periodical that contained similar content by Beard, sold for twenty cents per issue.

Special Collections' 1921 edition of The Jack of All Trades is missing its first few pages.

The intact 1900 edition, however, displays

the book's original price:

two dollars.

This 1921 edition of "Boys' Life: The Boy Scouts' Magazine" —at just twenty cents per issue—reveals the price difference between the book and the magazine.

Daniel Carter Beard, the author of The Jack of All Trades, was also the editor of and a regular contributor to "Boys' Life," which contained similar content to that of The Jack of All Trades.

Further comparison between "Boys' Life" periodicals and The Jack of All Trades highlights the

peculiarity of the book's form.

The periodical's layout is more complex; as with most magazines, multiple articles appear on the same page and then continue near the back of the magazine. Text appears cluttered, uneven, and is often interrupted by illustrations.

The layout of The Jack of All Trades appears much cleaner, which offers a more streamlined reading experience than the periodical can provide. Sturdy and compact,

the physical book seems to present itself as a tool

that readers could take with them on the adventures that it promotes: to a tree-top clubhouse, a backyard workshop, or a homemade "Daniel Boone cabin."

Although the entire book mimics the layout of a manual, only parts of it provide instructions for readers. As this example from the text showcases, a large portion of the text is narrative, with some words

(seemingly arbitrarily)

printed in bold in order to give the illusion that the entire text acts as a manual.

The Author

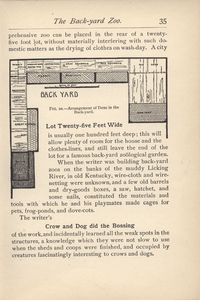

The Jack of All Trades gains significance when we consider its author. Daniel Carter Beard founded an organization for boys called “The Sons of Daniel Boone,” which merged in 1910 with Ernest Thompson Seton’s similar organization “Woodcraft Indians.”

Together, they became The Boy Scouts of America.

The purpose of The Boy Scouts of America was to "utilize the boy’s leisure time under competent and sympathetic leadership, to popularize a large number of outdoor games and occupations of various sorts in which each boy [could] have a full share, and to provide incentive that [would] attract and hold the boys by means of a compact, well-organized national body” (Anderson 708). The Jack of All Trades was first published just ten years before Seton and Beard officially formed The Boy Scouts of America, and

Beard's text explicitly promotes an ideology similar to that of the organization.

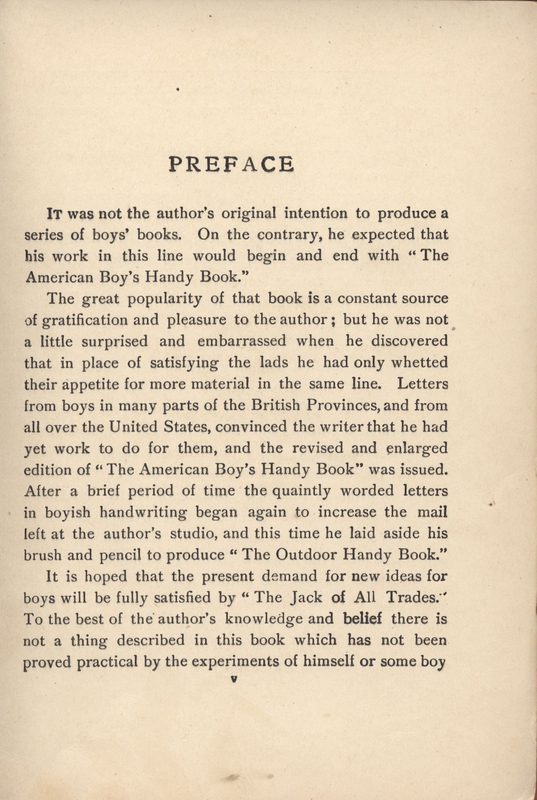

As you can see below in the "Preface" to The Jack of All Trades, the book, like the Boy Scouts organization, aimed to cultivate in boys a

specific brand of American masculinity:

one that privileged "outdoor skills (but not formal athletic games as such), woodcraft skills, and, increasingly, ... skills that derived from growing technology" (Anderson 708). This masculinity pushed for a resourcefulness and self-reliance in men "in a nation that was rapidly coming of age" (708).

The Ideology

The following excerpt from Beard's "Preface" to The Jack of All Trades states the book's ideology and purpose explicitly, and reiterates the values that both the book and The Boys Scouts of America promote. Beard creates a narrative thread in the "Preface" in which play and resourcefulness training in youth lead to both mental and physical strength and vitality, which in turn offers the opportunity to cultivate optimal masculine character in adulthood. Beard often offers quintessential American historical leaders —in this case, Abraham Lincoln— as examples and he elucidates that this "strong manly character" (vi) not only rejects femininity, but it also

defines itself in part by whiteness.

He writes that "there can be little doubt that the rude schooling and hard knocks of a pioneer’s life rejuvenated our race and developed those qualities in the characters of Americans" (vi). Scholar Ben Jordan points out that the ""closing of the frontier," rapid urbanization, corporate bureaucratization, the "New Woman," the "New Negro," and "new immigrants" from southern and eastern Europe challenged native-born white men's authority at the turn of the twentieth century" (616), and these shifts surely provoked white insecurities and contributed to the nation's call for a new masculinity that intended to advance white men. Jordan notes the tendency of The Boy Scouts of America to honour figures such as "Washington, Lincoln, Daniel Boone, and Davy Crockett as pioneer Scout ancestors" and to "point to [these figures] as evidence of the triumphant evolution of white American men and their nation-state" (619).

Excerpt from the "Preface" to The Jack of All Trades:

"It is now a generally accepted truth that the so-called skill of the hand is in reality the skill of a trained mind. The necessity, in work or play, of constantly overcoming new obstacles and solving new problems, develops a strong and normal mind and body. There can be little doubt that the rude schooling and hard knocks of a pioneer’s life rejuvenated our race and developed those qualities in the characters of Americans, without which Washington would have been but a country gentleman and Lincoln a village store-keeper. Had little Abe Lincoln been reared under the care of a foreign woman with cap and ribbons (i.e. a French nurse), his strong manly character would never have been developed and our country would have lost one of its grandest patriots and history its most unique figure.

Aside from these vitally important facts, art demands that our youth should be encouraged to do things for themselves, to produce things by their own labour. The most finished product of the machine cannot appeal to the heart of a real artist as does some useful and homely object which still bears the marks of its maker’s hands.

For these reasons the author hopes that parents will allow their boys to be boyish boys; and in order to keep them out of mischief they will cater to the lads’ natural and healthy desire for entertainment by encouraging them in all rational projects and supplying them with tools and materials, so that the boys may all become juvenile Jacks of All Trades" (vi).

Explicit Racism

We need not look far to find racism in the networks —both of people and of systems— that surround The Jack of All Trades. In Building Character in the American Boy: The Boy Scouts, YMCA, and Their Forerunners, 1870-1920, David Macleod presents the racist ideology of The Boys Scouts organization very explicitly.

An excerpt from his text:

"The first American Boy Scout handbook included [Robert] Baden-Powell's mnemonic device for "N" in Morse code, a cartoon of a "Nimble Nig" (the dot) chased by a crocodile (the dash). Although seldom as blatantly nasty as Baden-Powell's joke—indeed generally fairly mild by standards of the early twentieth century, when vicious racism pervaded much of white American culture— heedless bigotry was commonplace among character builders" (212) such as Scout leaders.

In his work Macleod also compiles recruitment and enrollment data for The Boy Scouts, and he concludes that members "were disproportionately middle class" because "enrollment patterns ... had historical roots in decisions— made before 1900 and sustained thereafter— to favor middle-class boys and guard them from lower-class contamination" (212). Macleod also writes that black boys may have been excluded from the organization because many still lived in rural areas, but that "their neglect also reflected the casual racism which permeated contemporary ... American culture" (212). He narrows in on

Daniel Carter Beard's ideology

specifically, when he writes:

"Although the degree of selectivity in Boy Scout recruitment was not immediately apparent, Beard for one had the impression that Scouts belonged 'to the better class' of boys. 'They were a fine lot of lads,' [Beard] said, 'but apparently they were a fine lot of lads before they joined'" (218).

This is important,

not only because it reveals the racist underpinnings of The Boy Scouts of America and the culture from which it, as well as Beard's text, comes, but also, more significantly,

because it provides evidence that suggests that whiteness is directly cultivated by a response to non-whiteness.

The Boy Scouts was not a group that simply —for the most part—excluded non-white members. It was an organization that worked to construct and disseminate a type of masculinity that exclusively advanced its own members, which were overwhelmingly, and not accidentally, young white boys. As previously stated in the section entitled "The Book," The Jack of All Trades physically presents itself as tool. Boys could implement this tool in order to achieve the type of masculinity that both the book and The Boy Scouts organization privileged. That only boys already of a certain class had access to this tool (which cost two dollars at the time of its publication) suggests that this book was not intended to facilitate boys lower on the socioeconomic ladder in an attempt to rise to superior masculinity. Similarly, Boy Scouts membership was largely restricted to white boys because many "lower-class boys found the [program not only] costly [but also] culturally alien" (Macleod 212).

Implicit Racism

“National literatures, like writers, get along the best way they can, and with what they can. Yet they do seem to end up describing and inscribing what is really on the national mind. For the most part, the literature of the United States has taken as its concern the architecture of a new white man” (Morrison 14-15).

In Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination, Toni Morrison writes about the ways in which a conscious or unconscious fear of blackness shapes American literature. She suggests that concerns such as “autonomy, authority, newness and difference, [and] absolute power … not only become the major themes and presumptions of American literature, but that each one is made possible by, shaped by, activated by a complex awareness and employment of a constituted Africanism” (44).

Africanism: “a term for the denotative and connotative blackness that African peoples have come to signify” (Morrison 6).

Morrison focuses her analysis on the ways in which blackness appears at the periphery in Modern American fiction, in the form of seemingly insignificant characters, or of “tropes of darkness, sexuality, or desire” (14). She specifically discusses work by Edgar Allen Poe, Herman Melville, Willa Cather, Henry James, Flannery O’Connor, Gertrude Stein, William Faulkner, and Ernest Hemingway. Morrison argues that while these appearances by a “dark, abiding, signing Africanist presence” seem minor, they in fact may have produced “the major and championed characteristics of [American] national literature— individualism, masculinity, and social engagement"(5). Although Morrison’s theory concentrates on Modern American fiction, it sheds light on Daniel Carter Beard’s The Jack of All Trades: New Ideas for American Boys

as a significant artifact of the Modern era.

Blackness does not appear explicitly in Beard’s text. However, by contextualizing the book within the networks in which it was produced I hope to show that a fear such as the one that Morrison theorizes may have contributed to its formation. Morrison's work urges us to look not just at texts, but also at what sits at the periphery, in the background, and under the surface of them.

What informs a text? What shapes it? To what is it responding?

The following section examines a seemingly innocuous (or positive, even,) aspect of The Jack of All Trades: its push for young boy readers to show kindness to animals. I hope that by looking at Beard's text through the lens of Jordan's work will indicate just how the former was developed in response to something akin to Morrison's "Africanist presence." The material in the next section illuminates how both Beard and The Boy Scouts organization used the idea of being kind to animals to differentiate whiteness from non-whiteness. They promote the tendency to show compassion to animals as an inherently white trait that situates white people in a morally superior position.

“Explicit or implicit, the Africanist presence informs in compelling and inescapable ways the texture of American literature” (Morrison 46).

Kindness to Animals

In an early-twentieth-century text that promotes itself as a boy’s guide to masculinity, we might expect to find sections about hunting, conquering, and killing animals for survival in the wilderness. Instead, Beard encourages, right from his "Preface,” to The Jack of All Trades, kindness toward animals. He writes: “It is the object of the author, in the chapters devoted to animal life, to teach the boys to look upon all animals with the same thoughtful kindness with which they might view their own undeveloped brothers” (vii). This narrative thread runs heavily through the book; in fact, the emphasis on kindness to animals becomes so excessive that it draws attention to itself. In

Chapter II: Hunting Without A Gun,

Beard writes:

“Not long ago I attended a dinner given by the Camp-Fire Club, and there I found ranged around the table an array of veteran hunters. There were men there who had hunted the royal Bengal tiger in the jungles of India, men who had fought with rogue elephants, men who had followed the lions to their dens in Africa, men who had tracked the white bear to its lair in the far frozen North. … That [these men] were real simon-pure sportsmen could be seen at a glance, and yet, when the after-dinner speeches were made, the sentiments which received the most enthusiastic applause were those which DENOUNCED THE KILLING OF MAN OR BEAST. It could readily be seen that these men only used the gun when it was necessary to procure food of in self-defence. They all indorsed the use of the camera for the hunt in place of the murderous gun; as one of them remarked, “With a Kodak every good shot is registered with the click of the shutter, and an album of good shots is a thing of which any man may be proud” (19-20).

This chapter goes on to instruct readers how to identify, safely catch, and care for different animals. Beard’s over-the-top characterizations of rodents as mild, endearing pets seems to be an attempt to elicit compassion for them from readers. He describes flying squirrels as “the most gentle pets” (23), groundhogs as “remarkably gentle” (30), he writes about “gentle, graceful little jumping-mice” (23), and insists that “woodchucks make very gentle and comical pets” (27).

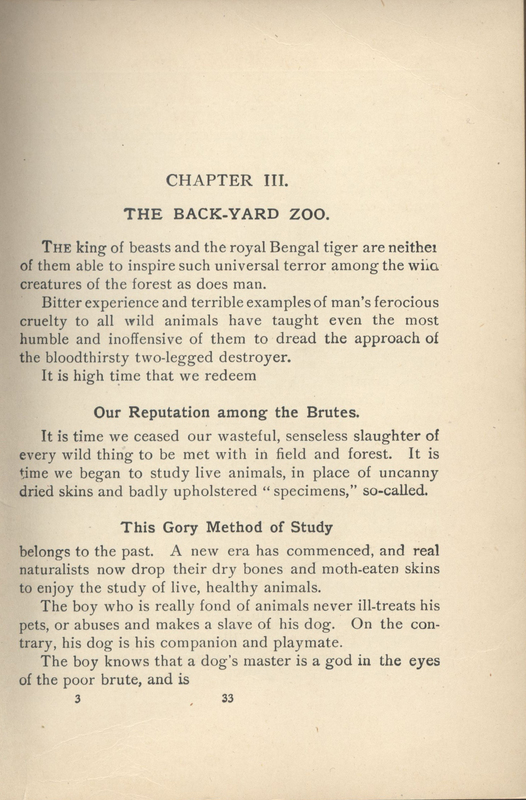

“It is high time that we redeem Our Reputation among the Brutes," Beard writes in Chapter III: Back-yard Zoo

This illustration, captioned "Visiting the Animals," depicts a boy's kindness toward his captives

Chapter IV: Back-yard Fish Pond

Chapter IV's accompanying illustration

In Chapter III, Beard teaches readers how to construct a

“Back-Yard Zoo” (33)

in order to care for their newly-caught pets. He offers instructions “To make a Cage of Galvanized Wire-Netting,” for all different kinds of animals.

This focus continues throughout the next several chapters:

Chapter IV: “A Back-Yard Fish-Pond” (48)

Chapter V: "Pigeon-Lofts and Bantam-Coops” (54)

Chapter VI: “How to make a Back-Yard Aviary” (63)

"National leaders argued that Boy Scouts' ability to conserve natural resources demonstrated their advanced character and justified their authority over black Americans, Native Americans, working-class immigrants, and females-groups characterized in BSA sources as being too primitive, selfish, or sentimental toward nature to conserve it” (Jordan 629).

Ben Jordan’s work shows that this emphasis on kindness to animals served to define and privilege “native born white, middle-class men attempting to maintain dominance over a changing nation” (613). Writing specifically about the principles that governed the Boy Scouts of America in the early twentieth century, he states that a shift from a “the virile yet selfish and primitive values attached to emulating frontier pioneers or Indians” to conserving and caring for natural resources “enabled the predominantly white, middle-class Scout boys and men to stay atop America's urbanization, corporate-driven mass production, scientific management, and progressive government” (613). To teach boys to conserve nature, then, was

an effort to “maintain white male dominance

over American society and its resource” (614). This information sheds light on certain aspects of Beard's prose, which might otherwise remain —at least marginally— veiled. For example, this quote that is displayed in the section above appears on page 33 of The Jack of All Trades:

“It is high time that we redeem Our Reputation among the Brutes. It is time we ceased our wasteful, senseless slaughter of every wild thing to be met with in field and forest.”

And this quote from the following page suggests kindness to animals as an avenue to a position of respected authority:

“A lad who loves his pets will bestow upon the little creatures that affection which shows itself in a sympathy which can understand their wants and necessities. Such a lad can perform wonders; birds will come at his call, the small beasts of the field

will follow at his heels,

and no child will fear him” (34).

Beard even relies upon another yet reference to a quintessential symbol of American masculinity (see above section entitled "The Ideology") in order to correlate kindness to animals with the specific type of masculine American superiority that his work encourages when he tells this story:

“All boys know that Washington loved his country, but few know that he was a bird-fancier. That the father of our country loved the native birds is attested by the fact that they built nests in the wooden wrinkles of his sleeves and in the hollow ends of the roll of parchment which he held in his hand. His favorite bird was the red-headed woodpecker. He had it on the brain, and although each year a brood of little red-headed birds were hatched in his head, the dear old patriot never made a wry face, but with a benign smile he gazed over the roof of the livery stable across the street” (63).

"We are right now, this very month, allowing the negroes and the poor whites of seven Southern states to slaughter the robins for the pot" (Cave 1).

"Officials stated that black Americans and Native Americans, like young children, were too savage and selfish to be capable of deliberate natural resource conservation" (Jordan 616).

Finally, Jordan refers to this article, which appeared in a 1913 issue of "Boy's Life." The article "urged Scouts to get their fathers to write congressmen in support of the McLean Bill for federal protection of migratory birds" (Cave 1). As the image above shows, the article both distinguishes and elevates its middle-class white readership by suggesting an inherent "advanced moral character" (1). The bottom of the page reads:

"we are right now, this very month, allowing the negroes and the poor whites of seven Southern states to slaughter the robins for the pot" (1).

Bibliography

Anderson, David D. "The Boy Scout Books and America in Transition." Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 8, no. 4, 1975, pp. 708-713, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.00223840.1975.00708.x

Beard, D.C. “From Dan Beard’s Duffel Bag.” Boys’ Life: The Boy Scouts’ Magazine June 1915

Beard, D.C. “Some Points on Camping.” Boys’ Life: The Boy Scouts’ Magazine, June 1921, p. 26,https://boyslife.org/wayback/.

Beard, Daniel Carter. The Jack of All Trades: New Ideas for American Boys. Charles Scribner's Sons, 1900.

Beard, Daniel Carter. The Jack of All Trades: New Ideas for American Boys. Charles Scribner's Sons, 1921.

Cave. Edward. “A Double-Barreled Announcement.” Boys’Life: The Boy Scouts’ Magazine, January 1913. 2.11

Jordan, Ben. "Conservation of Boyhood": Boy Scouting's Modest Manliness and Natural Resource Conservation, 1910–1930." Environmental History, vol. 15, no. 4, 2010, pp. 612-642, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25764486

Macleod, David I. Building Character in the American Boy: The Boy Scouts, YMCA, and their Forerunners, 1870-1920. Wisconsin UP, 1983.

Morrison, Toni. Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination. Vintage Books, 1993.

Nye, Russell. The Unembarrassed Muse: The Popular Arts in America. Dial Press, 1970.

D. O. / Fall 2018