Wilkie Collins - The Woman in White. Serialized in All the Year Round, Edited by Charles Dickens. (1859-60)

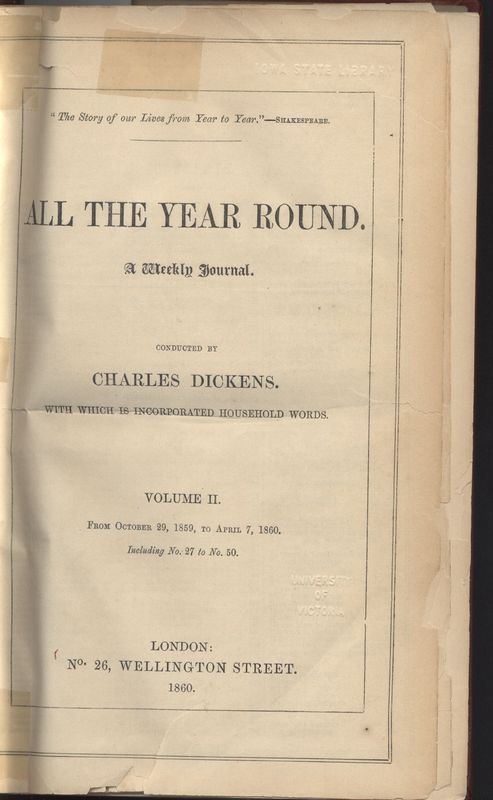

Here is the cover and spine of UVIC's Special Collections copy of Volume II of the collected All the Year Round, published in 1890, collecting issues 27 to 50, from October 29, 1859 to April 7, 1860. The Woman in White premiered in the November 25 issue. These collections of "family magazines" were very popular in the second half of the 1800s--binding the weekly magazine issues, with the advertisements stripped out.

The origins of the UVIC Special Collections copy, scanned here, are unknown, but the first page does have "University of Iowa," in blind embossing, on it--presumably where the volume was purchased from.

Images of the Title Page of Volume II of the collected and bound anthology edition of All the Year Round and the Table of Contents, which is on the back end-page of the volume. Here Wilkie Collins is credited as author of The Woman in White, due to the increase already in his fame, and the non-fiction articles are listed by subject with the serials given place of priority.

Of special interest is the the last listing, for the The Haunted House, which is from the Christmas 1859 Special Edition and is a portmanteau novella of interconnected ghost stories--ghost stories being typical of Dickens' Christmas work. While all unsigned, Dickens wrote "The Mortals in the House," "The Ghost in Master B's Room," and "The Ghost in the Corner Room" and Collins wrote "The Ghost in the Cupboard Room" with Elizabeth Gaskell, Adelaide Anne Procter, George Sala and Hesba Stretton writing the rest.

Charles Dickens and the Family Magazine

In 1850s England, Charles Dickens helped to pioneer a new style of periodical, the “family magazine,” with the weekly, Household Words, which he helped create and edit, starting in 1850. As Dickens wrote in the first issue's "A Preliminary Word": the goal of a family magazine was “to live in the Household affections, and to be numbered among the Household thoughts, of our readers. We hope to be the comrade and friend of many thousands of people, of both sexes, and of all ages and conditions, on whose faces we may never look. We seek to bring to innumerable homes, from the stirring world around us, the knowledge of many social wonders, good and evil, that are not calculated to render any of us less ardently persevering in ourselves, less faithful in the progress of mankind, less thankful for the privilege of living in this summer-dawn of time” (qtd. in Wynne, Sensation Novel 23).

Squarely targeting the middle-class, and at the affordable cost of just a tuppence an issue, these weeklies would come out on Saturdays when most people only worked a half day, and then be shared by the entire family, with a variety of articles, fiction and poetry aimed at every member of the household—and were meant to offer a middle-class, respectable alternative to the scandalous cheap weeklies and penny dreadfuls aimed at the working class. Household Words primarily published short fiction, but its serialized works, including Dickens’ own Hard Times (serialized from April to August 1854) and Elizabeth Gaskell’s North and South (serialized from September 1854 to January 1855), purposefully carried a social agenda (Wynne 25).

By 1859, however, Dickens had had a falling out with his publishers due to wanting more control over his magazine, and Household Words folded. Ever on the ball, Dickens launched his own weekly, All The Year Round, on the last week of April, 1859, a month before the final issue of Household Words. However, Dickens had sensed a shift in what middle class readers wanted to read, particularly when it came to fiction. All the Year Round placed its main focus on serializing long novels, giving each installment the opening pages of each weekly issue. Dickens also sensed a shift in the content that readers wanted, and focused less on the social issues that Household Words's fiction emphasized. All The Year Round premiered with the first installment of his own A Tale of Two Cities.

Despite its historical subject matter of the French Revolution, in A Tale of Two Cities, Dickens knew that he had to grab an audience who now wanted more visceral entertainment. Focusing on "sensations," Dickens made sure that each weekly installment was filled with violent incident and shocking events, leaving the reader anxious to read the next week's installment. The novel, and the magazine, were an instant hit (Wynne 45).

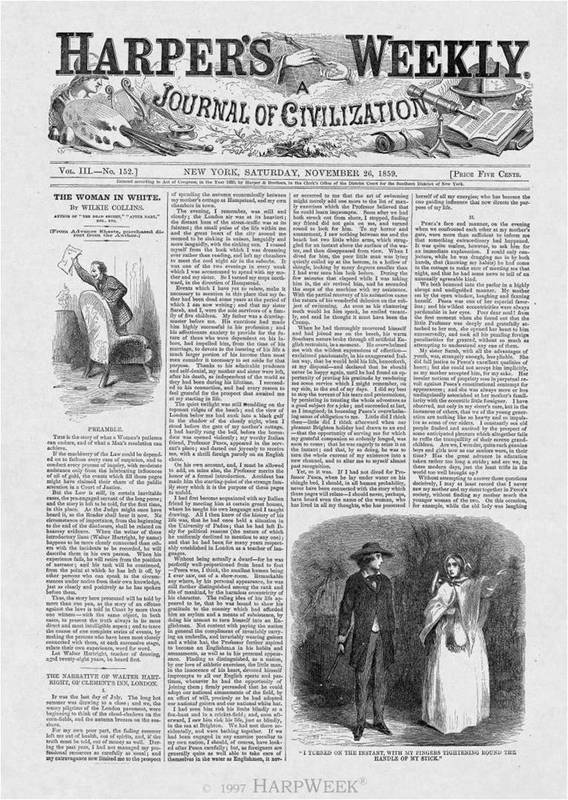

A few months later, in August, Dickens asked his friend Wilkie Collins, who had already had some limited success including writing for Household Words, to write the serial that would follow A Tale of Two Cities, emphasizing that it should also be a novel carefully focusing on exciting, weekly installments. Collins’ The Woman in White’s first installment appeared in the November 26, 1859 issue of All The Year Round, the same issue as Two Cities’ conclusion, a common technique to hook the reader on the new serial just as they were finishing the previous one.

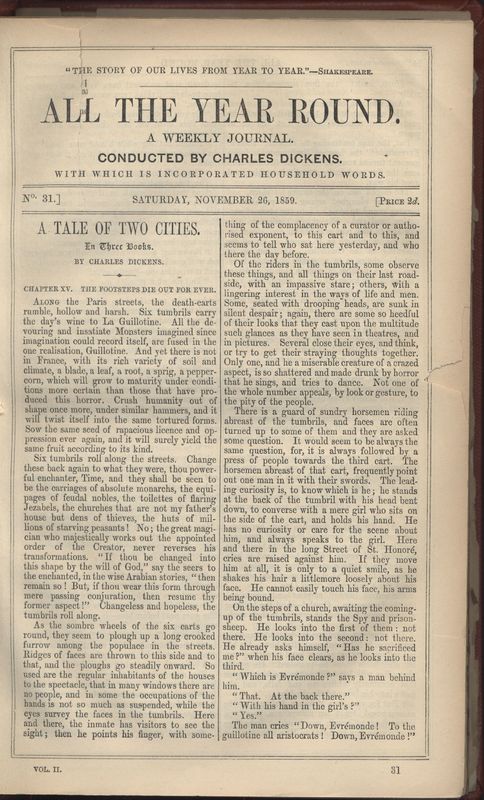

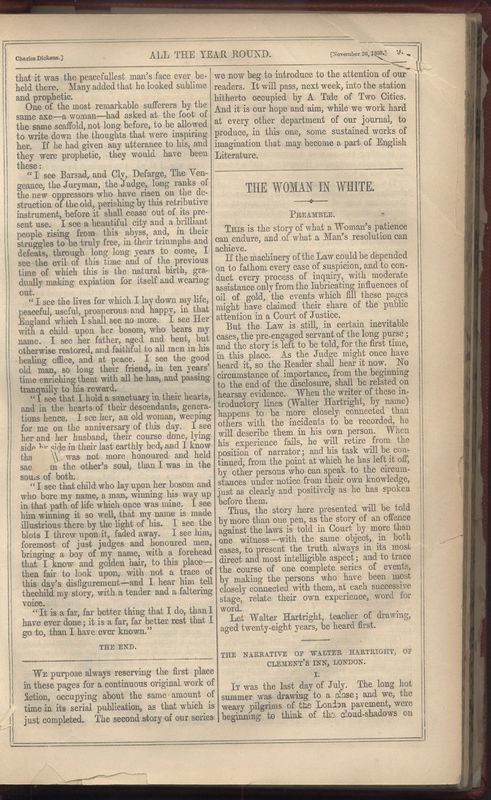

The first page of the November 26, 1859 issue of All the Year Round. This issue contains the last installment of Dickens' A Tale of Two Cities and the first installment of Collins' The Woman in White.

The start of the first installment of The Woman in White. The issue gives priority placement to the conclusion of A Tale of Two Cities--future issues would open with each new installment of The Woman in White.

The first installment of the serialization of The Woman in White immediately followed the end of the final installment of A Tale of Two Cities. Dickens' format for All The Year Round was similar to a newspaper, with no illustrations, text presented in columns, and each story or feature immediately following the previous one. As was common with Dickens' previous periodicals, the only author to get credit was Dickens himself--so The Woman in White is presented without a signature.

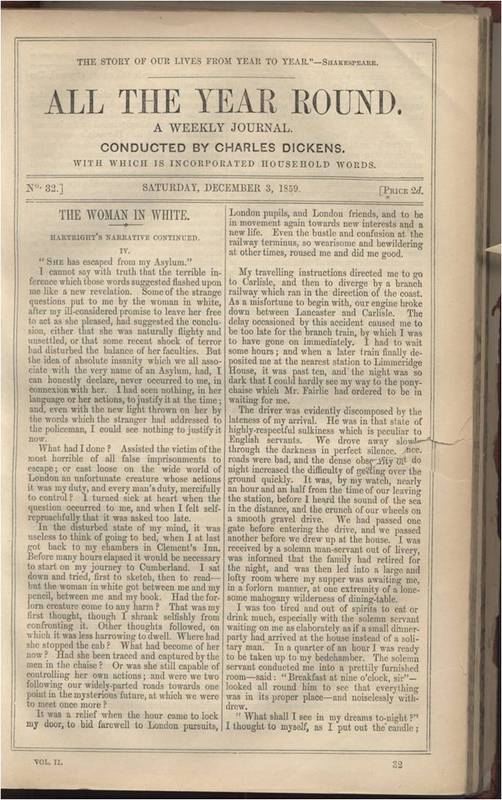

All the Year Round Dec. 3, 1859 Issue

The second installment of The Woman in White

and the first time it was featured on the front page.

The First Sensation Serial

The sensation serial fiction craze is generally credited as starting in 1860, with the final installment and subsequent book publication of Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White, and essentially coming to a close by the end of the decade. However, it is not quite that simple in reality. As Patrick Brantlinger points out, sensation novels did not come out of a vacuum, being a “unique mixture of domestic realism with elements of the Gothic romance, the Newgate novel of criminal ‘low life’, and the ‘silver fork’ novel of scandalous and sometimes criminal ‘high life’” (1). In other words, this was a mixture of popular and high culture forms—the realism movement then held in high regard in Victorian literature being appropriated, some might say corrupted, by low culture.

Wilkie Collins followed the formula of ensuring that each weekly installment would have a moment of suspense, but tweaked the formula. Drawing from the various genres already listed by Brantlinger, but perhaps most especially from the Gothic, Collins formulated a novel that featured such outlandish elements as doppelgangers, false incarcerations, foreign villains, corrupt noblemen, illegitimate children, and even the hint of the supernatural with dream premonitions. However, to make all of these elements compelling, yet feel believable, he carefully set them in a finely detailed, contemporary setting—one that contemporary English readers, particularly those in London, would completely recognize as their own.

A recognizable, contemporary setting was Collins’ true innovation with The Woman in White, and that would become a key trait of the sensation novel in general. As Henry James wrote in 1865,

[The Woman in White], with its diaries and letters, was a kind of nineteenth century version of “Clarissa Harlowe.” Mind, we say a nineteenth century version. To Mr. Collins belongs the credit of having introduced into fiction those most mysterious of mysteries, the mysteries which are at our own doors. This innovation gives a new impetus to the literature of horrors. It was fatal to the authority of [the Gothic author] Mrs. Radcliffe and her everlasting castle in the Apennines. What are the Apennines to us, or we to the Apennines? Instead of the terrors of “Udolpho”, we were treated to the terrors of the cheerful country-house and the busy London lodgings. And there is no doubt that these were infinitely the more terrible. Mrs. Radcliffe’s mysteries were romances pure and simple; while those of Mr. Wilkie Collins were stern reality. The supernatural, which Mrs. Radcliffe constantly implies, though she general saves her conscious, at the eleventh hour, by explaining it away, requires a powerful imagination in order to be as exciting as the natural, as Mr. Collins and [fellow sensation novelist] Miss Braddon, without any imagination at all, know how to manage it . . . Less deliberately terrible, perhaps, than the vagaries of departed spirits, but to the full as interesting, as the modern novel reader understands, are the numberless possible forms of human malignity. The nearer the criminal and the detective are brought home to the reader, the more lively his “sensation.” They are brought home to the reader by a happy choice of probable circumstances; and it is through their skill in the choice of these circumstances—their thorough-going realism—that Mr. Collins and Miss Braddon have become famous. (110-11)

An example of how Dickens carefully chose articles for each issue of his magazine that would relate or support elements of The Woman in White. "Italian Distrust" relates thematically to the Italian element of the serial.

The Magazine Supports the Story

A key element to support the realistic framework for its unrealistic sensations in The Woman in White, and indeed in sensation novels throughout the decade, was that it was serialized in a weekly periodical. Readers followed along with these characters and their story in installments which, while the narrative did not follow the actual week to week time-frame, nonetheless the readers lived with the narrative on a week to week basis for a year, or however long the novel would take to be serialized, at a time. To keep readers coming back week after week, each installment would generally end with a cliff-hanger. Even the sensation elements of Collins’ novel reflect contemporary Victorian England. Collins’ narration obsesses with details of time and date, relies on relatively recent innovations such as the British railway and postal systems, and plays on fears of how these innovations, that so many rely on, can fail, as in the many tampered letters in the novel. While the novel uses the Gothic trope of false imprisonment, Collins transforms this into false incarceration in a mental asylum, which was a contemporary fear. As editor-in-chief (or “conductor” as he titled himself), Dickens sought to reinforce this sense of reality in the magazine itself, filling each issue with articles, and even sometimes advertisements, that would intertextually comment on aspects of each installment of The Woman in White. For example, Dickens ran a series of articles about “Convict Capitalists” which specifically mentioned forgers, “emphasizing the connection between Glyde and these gentlemen forgers” (Wynne, Sensation Novel 53). Similarly, “’The Breath of Life’, detailing the dangers of typhus fever, appeared in the same issue as the episode . . . where Marian displays the same symptoms” of this disease (46). Dickens’ target for All the Year Round was, as implied by his categorizing it as a family magazine, the entire family. Sold for the cheap price of a tuppence an issue, and released on Saturdays when the Victorian middle class would only work half-days and were expected to spend the remainder of the day doing family activities, the magazine was intended to then become a part of the household for that week, where various family members could pick it up and peruse it at leisure, or, as was reportedly common with its serial installments, read it out loud together. This meant that the magazine, and the characters and stories of its continuing serialized novel, would become a weekly constant in the household, a source of entertainment that could be taken for granted. It also helped encourage middle-class society to discuss what had happened in each installment, and question what future lay ahead for their favourite characters.

Collins’ serial brought the circulation of All the Year Round to over 100,000, nearly double that of its closest rival week, Once a Week (Wynne, Sensation Novel 25). However, with The Woman in White’s enormous success and influence, both on future serialized novels for All the Year Round and in rival family magazines, society grew increasingly alarmed about the actual sensation contents of these novels and the very fact that they were rather innocuously hidden away in weekly magazines that had become such an accepted part of middle-class households. Just as the sensation genre disrupted a realistic depiction of contemporary Victorian England with sensational elements, so too did the serialized novels themselves disrupt the seemingly wholesome family magazine, and the middle class household itself.

For the price of £1000, Dickens allowed Harper's Weekly to publish All the Year Round's serials concurrently with their UK publication. This was done by shipping stereotype plates of the text overseas, one week in advance. Harper's, being a higher-end weekly than All the Year Round, illustrated, by artist John McLenan, each installment of their serials.

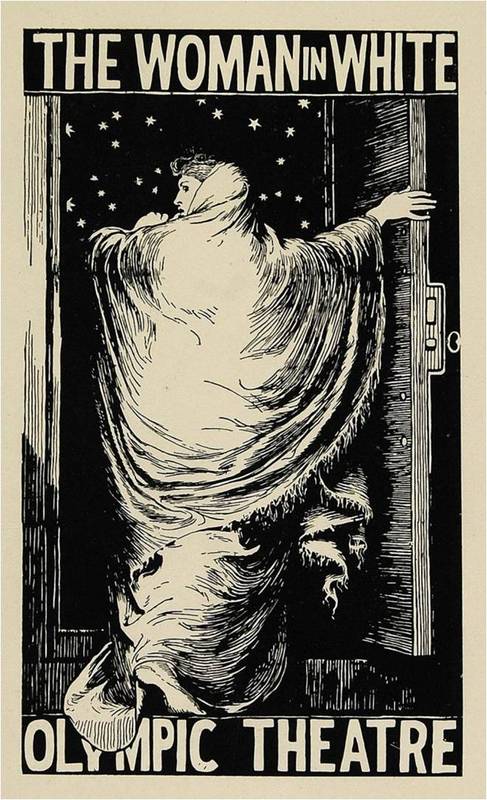

Poster for Collins' own 1871 stage adaptation, one of several stage versions. Illustration by Freederick Walker.

The 1860s Sensation Craze

Collins’ serial was not just a pop cultural phenomenon—with everything from perfumes, cloaks and bonnets, to popular music and dance crazes, based on it—but was also a critical success, with even the less glowing reviews praising its ingenuous construction. This praise continued throughout the 1860s. Margaret Oliphant in her review of Charles Dickens’ later All the Year Round serial, Great Expectations, compared Dickens’ work unfavourably to that of Collins. Identifying Great Expectations as a follow-up sensation serial to The Woman in White, Oliphant found Dickens’ attempts at sensation elements, particularly with the character of Mrs. Havisham, as “fancy run mad,” in contrast to the clever ways Collins incorporates the sensation (“Novels” 259). This is especially noteworthy because, soon after, Oliphant would become one of the most vocal in the backlash against sensation serials, which quickly became seen as at best, a cheap product that was churned out and took away from the popularity of genuine literature, and at worst, an actually dangerous moral influence on the middle classes, in particular on the female and the young. As sensation serials became more prolific in the 1860s, the worry about their influence on the reader grew. Margaret Oliphant, while praising The Woman in White, despaired that,

Middle-class morals are in danger of being eroded by the violent stimulant of sensation fiction serial publication—of WEEKLY publication with its necessity for frequent and rapid recurrence of piquant situation and startling incident. It’s the thing of all others most likely to develop the germ, and bring it to fuller and darker bearing. What Mr. Wilkie Collins has done with delicate care and laborious reticence, his followers will attempt without any such discretion. (“Sensation Novels” 568)

Indeed, even more hysterical concerns over their effects followed:

There is no accounting for tastes, blubber for the Eskimo, half-hatched eggs for the Chinese, and Sensation novels for the English. Just as in the Middle Ages people were afflicted with the Dancing Mania and Lycanthropy, sometimes barking like dogs, and sometimes mewing like cats, so now we have a Sensational Mania. Just, too, as those diseases always occurred in seasons of dearth and poverty, and attacked primarily the poor, so does the Sensational Mania in Literature burst out in times of mental poverty, and afflict the most poverty-stricken minds. (“Belles Lettres” 269-70)

Such editorials about the dangers of sensation novels were not uncommon since sensation novels were viewed as a negative influence on their readers. Aspects, such as bigamy, that had been tolerated in penny fiction—serials that were aimed at the lower classes—were now seen as a threat to middle-class homes. One of the main targets were the sensation serials of Mary Elizabeth Braddon, an author who wrote that Collins was her “literary father” and that she owed her work to The Woman in White. A former writer of penny fiction, Braddon found a striking success with Lady Audley’s Secret. Taking elements from Collins, such as a character with a secret past, that would keep readers excited for each installment, Braddon added the element of bigamy. The heroine of her novel, Lucy Audley, will do anything to keep her status as a noble woman—including throwing her first husband down a well, just to preserve her position. The reader is meant to identify with Lady Audley, which is the cause of much of the criticism of the novel, and of sensation fiction, as critics suspected women readers may be influenced by her actions. Braddon was particularly targeted by critics not just due to the content of her serials, but also due to it being connected by critics to her own unconventional living situation—she bore the publisher John Maxwell six children while his wife was institutionalized and only married him after the wife’s death in 1868—and due to her immense output. “From 1862 until the end of the decade, in addition to continued anonymous work, Braddon had at least two serials running each year in a wide range of periodicals” (Pykett, “Braddon” 125). The majority of these novels repeated the sensation formula which she had helped create with Lady Audley, “deploying variations on the same stock ingredients: bigamy, murder, disguise or impersonation, madness, blackmail, fraud, theft, kidnapping or incarceration and inheritance plots” (126). Oliphant, writing in 1867, condemned Braddon for leading a genre that focuses on,

"Women driven wild with love for the man who leads on to desperation before he accords that word of encouragement which carries them into the seventh heaven; women who marry their grooms in fits of sensual passion; women who pray their lovers to carry them off from husbands and homes they hate; women who give and receive burning kisses and frantic embraces either waiting for or brooding over the inevitable lover; women who wait now for flesh and muscles, for strong arms that seize her, and warm breath that thrills her through, and a host of other physical attractions which she indicates to the world with a charming frankness. It is painful to inquire where it is that all these stories of bigamy and seduction come from. They have taken, as it would seem, permanent possession of all the lower strata of middle-class light literature" (“Novels” 258-59).

Braddon sought to fight back against the backlash to sensation serials in some of her later works, such as The Doctor’s Wife in 1864, an unauthorized adaptation of Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, in which, through the title character, Braddon “seeks to demonstrate that ‘dangerous reading’ is a particular practice of reading rather than a matter of content or genre,” but such moments of self-reflection about her genre, in her serials, seems to have gone without notice until modern re-evaluation (Pykett, “Braddon” 127).

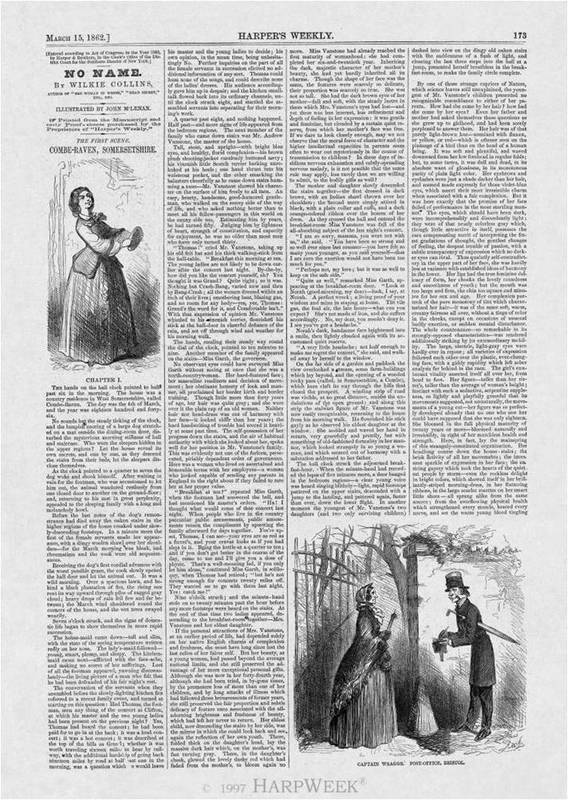

The first installment of Collins' No Name in Harper's Weekly, 1862. Illustrated by John McLenan.

The first installment of Collins' The Moonstone in Harper's Weekly, 1868. Illustrated by John McLenan.

Sensation Backlash

Aside from Collins, the major authors of sensation novelists were female, with Braddon heading up the list but with Ellen Wood’s hugely successful East Lynne, from 1861, and its story of a woman who tries to reclaim her rights as a wife after being disfigured, while being involved in an extramarital affair, by returning to her family in secret as a governess, also significantly shaped the public view of sensation serials. Because so many of these authors were women, this further caused critics to associate the genre with females. Since these serials were published in family magazines, they were easily read by every member of the family. As Deborah Wynne writes, “The morally uplifting realist novels of writers such as Walter Scott, Jane Austen, William Thackeray and George Eliot had, by the 1860s, contributed to the acceptance of the novel as a literary form capable of the heights of the drama and poetry” (“Critical Responses” 392).

This new generation of sensation writers, Collins, but especially Braddon and Wood, were seen then to be corrupting the realist agenda and tarnishing it with their own morals. H. L. Mansel, the Professor of Moral and Metaphysical Philosophy at Oxford, wrote in the conservative Quarterly Review, in 1863, that sensation novels attacked the values of “English Literature,” and, unlike the long-standing penny fiction aimed at the working class, the danger was that they were infiltrating the respectable literary marketplace. This was aggravated by the feeling that sensation novels, like penny fiction, felt like a constantly churned out product, one that was ephemeral compared to “English Literature,” and cranked out to fill an insatiable appetite. Mansel went on to say that the serialized nature of sensation, and its “preaching to the nerves” (482) stimulated readers until they resembled “dram drinkers” in the “grip of perpetual craving” (485). Of course the implied audience who would be most harmed by this were the female readers, with Henry Chorley in a review of “New Novels” in the Athenaeum in 1886 claimed that contemporary women were “unstable and particularly susceptible to new trends . . . and that their ideas on point of morals and ethics seem in a state of transition and confusion” which these novels played into (qtd. in Wynne, “Critical Response” 391). Combining these critiques, the fear was that the “overly-lively” heroines of working-class melodrama and penny fiction had been imported into the respectable middle-class home via sensation fiction (Oliphant “Novels” 258).

While the sensation craze died after the 1860s—Wilkie Collins, who had been called one of the best novelists of his times became derided in the press as “simply” a sensation writer by the 1870s—sensation elements continued in fiction, including in such literary fiction as that of Thomas Hardy. Is the scene where Tess follows a sleepwalking Angel to a graveyard where he tries to pull her into a coffin with him, any less “sensational” than anything Collins could write? Sensation elements also became common in fin-de-siècle urban Gothic fiction, such as Dracula and The Portrait of Dorian Grey.

Wilkie Collins contributed two more popular sensation serials to Dickens' All the Year Round: No Name (March 1862-January 1863) and The Moonstone (January-August 1868). Dickens passed away in 1870, symbolically just as the sensation craze had died. His weekly magazine continued until 1895 under the direction of his son, Charles Dickens, Jr. , but with far less focus on sensation serials, instead publishing more "literary" works by authors such as Anthony Trollope. Collins continued to write until his death in 1889, but, due partly to being associated with the sensation genre, his reputation and success had diminished. The Woman in White, however, has continuously remained in print through to the present day.

Questioning "Authorship"

Authorship of serialized fiction published in Victorian periodicals, due to the control that the editor would have over the magazine contents. As this historical and critical research shows, in the case of The Woman in White and its publication in All the Year Round, the authorship can be seen a number of ways. The serialized novel itself is by Wilkie Collins, however, as it was published in Charles Dickens' magazine--and initially with no signature to anything in the magazine except Dickens' own as "conductor," contemporary readers probably connected it to Dickens. They would buy the magazine because of Dickens', not Collins', name. Or, once hooked on a serial, they would buy the magazine for that serial title itself..

Once The Woman in White did establish Collins' name, and as shown it did so very quickly (including the fact that this collected volume does use his name in the table of contents), the authorship would surely be attributed more to him than to Dickens. However, as also shown, sensation serials quickly became a controversial subject and Collins' reputation eventually became associated with the genre. How much can genre itself be seen as a sort of authorship? If reader's are attracted to a title due primarily to its genre, and not its actual writer, does that take the place of authorship, at least for the reader?

For More...

This online exhibit has pages on two earlier periodicals that Dickens' worked at as editor--Bentley's Miscellany, a monthly he was at in the late 1830s, and the previously mentioned Household Words.

Wilkie Collins' The Woman in White is available online to read, albeit in its slightly revised book form--which eliminates passages of "recap" that would remind a serial reader of what came before, as well as re-structures certain chapters.

Finally, the Wilkie Collins Information page, an independent resource not connected to UVIC, has a full biography and bibliography, as well as details about many of the different editions of The Woman in White in book form.

Works Cited

All the Year Round, vol. 2. London, Charles Dickens, Chapman and Hall, 1860. University of Victoria Special Collections Call # AP 4 A4

"Belles Lettres." Westminster Review, vol. 30, no. 1, 1866, pp. 268-280. British Periodicals, search.proquest.com.ezproxy.library.uvic.ca/docview/8010542?accountid=14846.

Brantlinger, Patrick. "What is ‘Sensational’ about the ‘Sensation Novel’?" Nineteenth-Century Fiction, vol. 37, no. 1, 1982, pp. 1-28. JSTOR, doi:10.2307/3044667.

James, Henry. “Miss Braddon.” First pub. Nation, 1865, reprinted in Notes and Reviews, with a Preface by Pierre de Chaignon la Rose: A Series of Twenty-Five Papers Hitherto Unpublished in Book Form. Dunster House, 1921, pp. 108-116. Internet Archive, archive.org/stream/notesandreviewsw00jameuoft#page/108/mode/1up.

Mansel, H. L. “Sensation Novels.” The Quarterly Review, vol. 113, no. 226, 1863, pp. 481-514.

[Oliphant, Margaret.] "Novels." Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, vol. 102, no. 623, Sept. 1867, pp. 257-280.

---. "Sensation Novels." Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine, vol. 91, no. 559, May 1862, pp. 564-584. British Periodicals, search.proquest.com.ezproxy.library.uvic.ca/docview/6548493?accountid=14846.

Pykett, Lyn. “Mary Elizabeth Braddon.” A Companion to Sensation Fiction, edited by Pamela K. Gilbert. Wiley-Blackwell, 2011, pp. 123-133.

---. “The Sensation Legacy.” The Cambridge Companion to Sensation Fiction, edited by Andrew Mangham. Cambridge UP, 2013, pp. 210-223.

Wynne, Deborah. “Critical Responses to Sensation.” A Companion to Sensation Fiction, edited by Pamela K. Gilbert. Wiley-Blackwell, 2011, pp. 389-400.

---. The Sensation Novel and the Victorian Family Magazine. Palgrave, 2001.

Photos courtesy of UVIC Special Collections and www.wilkie-collins.info (used with permission)

EHG / Fall 2016