Stephen Crane, War is Kind (1899)

curious little book

It was somewhat by accident that I discovered the first edition of Stephen Crane’s War is Kind. While killing time in the library I requested everything Special Collections had by and about Crane. Before long the librarian trotted out a healthy stack: Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, George’s Mother, Active Service, and others, all books I have never managed to stumble over at my favourite bookstore in any edition or condition. At first I flipped through them politely, the way you do when a professor passes a book around the classroom. Then I saw this curious little book.

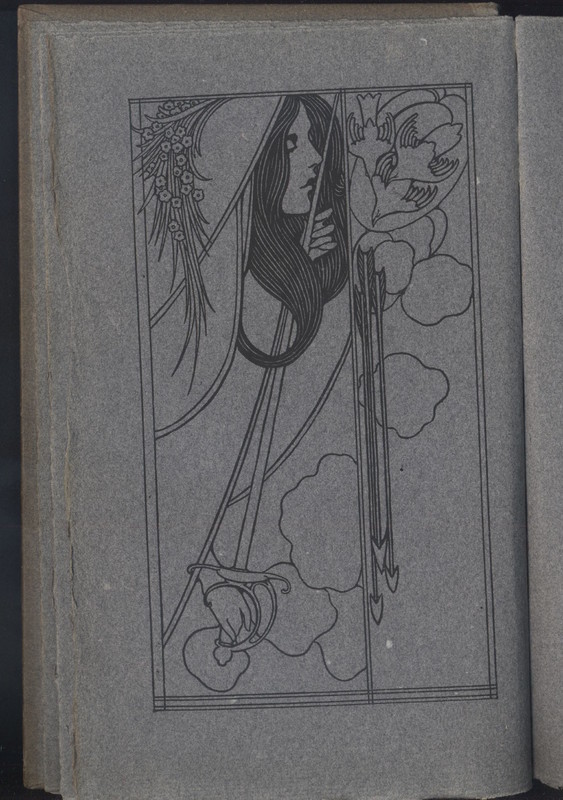

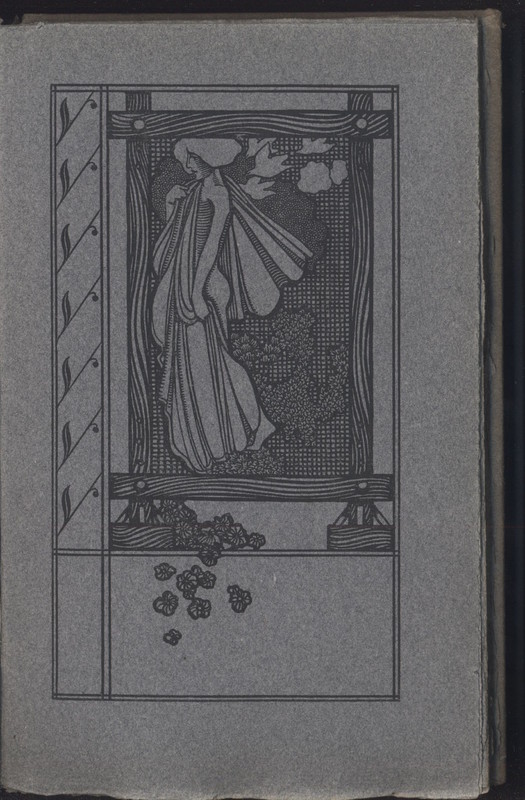

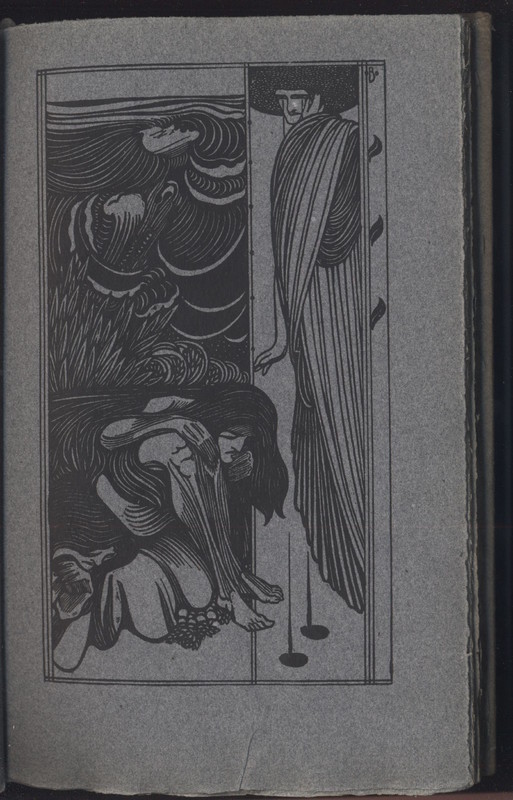

The cover and all of the proceeding illustrations are the work of one William H. Bradley, a pioneer of the art nouveau movement and, according to Wikipedia, the highest paid artist of the twentieth century, though I have yet to find anything to substantiate that claim. Nonetheless, scathing reviews of Crane’s collection also bear distaste for Bradley’s work: “The less said of Mr. Bradley’s drawings the better” (Stallman 141); “[Bradley’s role as illustrator] is perhaps worse than Mr. Crane’s being purely imitative” (141). R.W. Stallman’s Stephen Crane: A Critical Bibliography does not contain a single positive review of either the poems or the illustrations. People seemed to hate Crane and his book with a particular fervour. I have never been taught a poem or a story by Stephen Crane. In fact, I am absolutely positive that no professor of mine has ever mentioned his name. And yet here I am, 119 years after the fact, writing about War Is Kind.

books, publishing, and the goal of this exhibit

Books are not the product of writing or writers. Writers fill notepads, fiddle with manuscripts, and wear out the floorboards of studio apartments. A book is the product of a distinct network that connects publishers, printers, agents, authors, and illustrators. Of course publishers often “buy” books from authors before the author has a word on paper. The network survives by anticipating the market for a book and in doing so sets the production of that book in motion. Unlike the weather, the climate of the market is, like all human networks, a level two chaotic system. Changing the network is inherent to the process of making predictions and capitalizing on them. Uncovering how Stephen Crane and War Is Kind fit into this complex network and what that says about the network itself is the goal of this exhibit.

War Is Kind does not have a Wikipedia page, which made researching this book all the more exciting. Once I read the reviews, I decided to let the poems remain mysterious and not think too critically about them until I knew just about everything there was to know about how they came to be. I wanted the book as an object to be pure in a way that would not be possible if I brought a critical eye to the text. Not that I tend to agree with a lot of nineteenth-century book reviewers, but I was worried that, even if I liked the poems, the mysterious, elegiac quality of this object would be neutralized.

our copy

The only thing that seems particularly interesting about our copy of War Is Kind is that it was a gift. The inscription on the flyleaf says

Merry Xmas =

Happy New Year

From your brother

Harry.

Harry and his brother or sister remain unknown to me. Due to the poor reviews and sales, bookshops likely had stacks of War Is Kind marked down to sell. Perhaps Harry liked the cover. Or maybe it was the deckle pages and the dark paper. Judging by the condition of the interior pages—rigid and nowhere bent, creased or curved—l believe it has never before been read cover-to-cover, which would make me the first, and that would really make our copy something of a microcosm for the history of this book.

effect of a cover

Bradley's cover for War Is Kind is essentially a collage of the illustrations that follow. Divided into frames are a longhaired woman carrying a sheathed sword and a number of objects, like a lamp, a potted plant, and some sort of stringed instrument. The design is reminiscent of Japanese woodblock printing but with a vaguely Grecian influence that seems to situate the poems in an epic context. All of the figures appear to be women and, aside from the swords, the objects depicted are exclusively domestic—mostly potted plants, flowers, and candles. The women have a mythological quality, framed in heroic and valiant poses. Without having read a word, Bradley's contribution guides interpretation toward an alternative to masculine archetypes of heroism in war. Having read Crane's The Red Badge of Courage (1895) just this past summer, I could not decide whether the juxtaposition Crane as a kind of pre-Hemingway and this flamboyant artwork was a total absurdity or a brilliant strategy on the part of the publisher.

reading into the network

Finding these dark gray deckle pages so late in the nineteenth century suggests that the publisher, Frederic A. Stokes Co., was marketing the collection as a status symbol. The emergence of clean edges and cheap paper led to multiple first editions of many books, one for the general reader and one for wealthy people to place nonchalantly in their foyers. That Stokes chose to commission an artist like Bradley corroborates the status-symbol theory. Bradley’s “drawings” would have been considered somewhat edgy in 1899, which is evident from the vitriol that spilled over in the reviews. Nonetheless, he was a well-known and financially successful artist by the time Stokes contracted him for the illustrations, and Stokes was first and foremost a businessman. His firm “leaned toward the popular and maintained a large list of children’s books” (The Crane Log, Wertheim & Sorrentino xlvi). So, it seems that Stokes Co. may not have been all that confident in the young writer. Why not hedge their bets by putting a relatively popular avant-garde artist on the cover?

Obviously, that plan backfired, but doubts about Crane’s ability to sell a book of poetry were not unfounded. I took to reading his correspondence with Frederick A. Stokes Co. and Stokes’ personal letters to Crane. From what I can surmise, Crane was shifty and broke and always asking for advances, which is more or less consistent with stereotypes about writers. Two letters from Stokes (dated September 5, 1899, and September 23, 1899, respectively) capture the gist of their publishing relationship.

Dear Mr. Crane:—

We have just received your cablegram asking us to regard the cabled word “accepted” as now withdrawn […] The contract, as it stands, is as binding on both of us as if it were in the most careful legal phraseology. We refer you to our very clear and careful letter of August 15th, and to your acceptance of this. As we read your recent cablegram we thought that our reply was one giving you an acceptable answer to it, as your question was, “Will you cable money?” (The Correspondence of Stephen Crane, Wetheim & Sorrentino 513)

And 18 days later:

Dear Mr. Crane:—

Of course, you understand clearly that we really did not care for this volume of short stories in itself at all, and feel that we shall lose money in its publication. […] We note your reference to our distrustfulness. This is hardly just. The agreement is favorable, […] more so in the opinion of one of the writer’s associates than is justified by the demand for your work. […] You do not quite seem to appreciate, also, the fact that we have no easy task before us in trying to rehabilitate the commercial standing of your work in book form. […] [T]he leading houses in the trade throughout the country have a strong prejudice against you and your work. […] We do not care to discuss the reasons for this prejudice, and whether it is just or unjust, except that it is probably due to the comparative failure of your books since “The Red Badge of Courage.” […] As we had already cabled you £50, we trust that it will not occasion you any inconvenience to wait until copy is in our hands before we send the remainder.

Sincerely yours,

Frederick A. Stokes Company

Frederick A. Stokes

President

(Ibid 521 – 523)

the language of the network

War Is Kind was published four months before Stokes composed these letters, which concern a collection of stories that apparently never materialized. Clearly, the publishing relationship had degenerated from when they first published Crane's work. Stokes' correspondence with Crane speaks directly to his chief concern as a publisher. Of course, the language of this network is essentially the language of capitalism. From "...you understand that we really did not care for this volume of short stories at all..." to phrases like "the demand for your work" and "you do not seem to appreciate that we have no easy task before us in trying to rehabilitate the commercial standing of your work," Stokes is trying to orient Crane within the network to which the author seems so oblivious. What is happening here really demonstrates the complexity of the publishing landscape: Crane made a deal with Stokes that meant they would publish the unpopular poetry and stories he enjoyed writing in exchange for the right to publish the more popular historical fiction that he wrote exclusively for money. Cranes mounting financial problems seem to have corrupted his output to the point that even the books he was supposed to be writing for himself became a burden and were rushed out for publication and payment. Though correspondence regarding the publication of War is Kind is few and far between, it seems to have been a smooth affair, comparatively.

My Dear Crane:—

Stokes is publishing shortly your book of verses “WAR IS KIND” which has been made up by him in a very attractive shape by Bradley. He is sending some copies to Heinemann to have him copyright it. […] You will remember that I wrote to Heinemann about the book a number of months back and he replied that he would not pay any advance but that he would publish the book on a royalty basis. Of course if you can do better with someone else, why I suppose you will do it.

Yours sincerely,

Paul R. Reynolds

(Ibid 466)

desperation

Paul R. Reynolds founded what is believed to be the first literary agency in the United States (McDowell), a significant contribution to the complexity of the publishing network. Along with Crane, his clients included giants like Joseph Conrad and George Bernard Shaw. From what I can gather in the letters, he had Crane's best interest in mind at every turn, and yet he represents another barrier between Crane and final version of his work. Heinemann, who had previously published Crane’s books in London, secured copyright, but War Is Kind was never published in England (The Correspondence of Stephen Crane, Wertheim & Sorrentino 467), and this was probably due to its poor reception in the United States. The letter above confirms that Crane had no knowledge of the strange presentation of his poems before publication, which is not unusual. Unfortunately, I have been unable to find out what, if anything, Crane thought about Bradley’s work, but it does as though he spent much time at all thinking about his books once they were published and after he had been paid for them. Such was the case with Crane’s brief, tragic, and prolific career—juggling projects, rushing manuscripts, and writing his publishers for more money so he could stay afloat long enough to contract another book and receive another advance. Joseph Katz, editor of The Complete Poems of Stephen Crane (1966), sees money as both the driving and ultimately destructive force behind Crane’s work.

[Crane] was finally pushed to transmute the verse into money […] This is the key to an otherwise troubling volume. [T]he aura surrounding War Is Kind […] is dominated by the careless off-handedness that Crane assumed in closing an affair of purely business interest. Frederick A. Stokes Company […] had made him outright loans, and had guaranteed several of his debts. In what was obviously an attempt to repay his obligation, or at least to stave it off, he collected many of his poems since the publication of The Black Riders, added a few he had on hand, padded with one that had been printed in the first book, and surrendered the agglomeration to Stokes as War Is Kind. (Katz xxxvi)

I find it hard to accept that this beautiful little book could be the product of such heartbreaking desperation, that this object bearing the author's name could be so far removed from the artist and the art.

death and legacy

A short poem from Crane’s first collection, The Black Riders, stands out to me now that I know a little more about his life and publishing career.

In the desert

I saw a creature, naked, bestial,

Who, squatting upon the ground,

Held his heart in his hands,

And ate of it.

I said: “Is it good, friend?”

“It is bitter—bitter,” he answered;

“But I like it

Because it is bitter,

And because it is my heart.” (Crane 5)

This was his tragic image of the artist, naked and vulnerable, forced to consume his own heart to stay alive.

Stephen Crane succumbed to tuberculosis on June 5, 1900, at 3:00 AM at age 28, a little over a year after publication of War Is Kind (The Crane Log, Wertheim & Sorrentino 443). Though roundly rejected by contemporary critics after some brief success afforded by his first novel, he did find lasting success among another, perhaps more important, literary network. Fellow writers admired Crane both personally and as an artist. These writers included Henry James, Joseph Conrad, H.G. Wells, Ford Maddox Ford, and many others.

Works Cited

Crane, Stephen. War is Kind. New York: Frederick A. Stokes. 1899.

Crane, Stephen, and Joseph Katz. Complete Poems. Cornell University Press, 1972.

McDowell, Edwin. “Paul R. Reynolds, Literary Agent For Many Top Writers, Dies at 83.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 11 June 1988, www.nytimes.com/1988/06/11/obituaries/paul-r-reynolds-literary-agent-for-many-top-writers-dies-at-83.html.

Stallman, Robert Wooster. Stephen Crane: A Critical Bibliography. The Iowa State Univ. Press, 1972.

Wertheim, Stanley, and Paul Sorrentino. The Crane Log: a Documentary Life of Stephen Crane, 1871-1900. G.K. Hall & Co., 1995.

Wertheim, Stanley, and Paul Sorrentino, editors. The Correspondence of Stephen Crane. Columbia University Press, 1988.

Wertheim, Stanley, and Paul Sorrentino. The Crane Log: a Documentary Life of Stephen Crane, 1871-1900. G.K. Hall & Co., 1995.

M. T. / Fall 2018