Heresies Magazine (1977-1993)

Front Cover of the first issue of Heresies from January 1977.

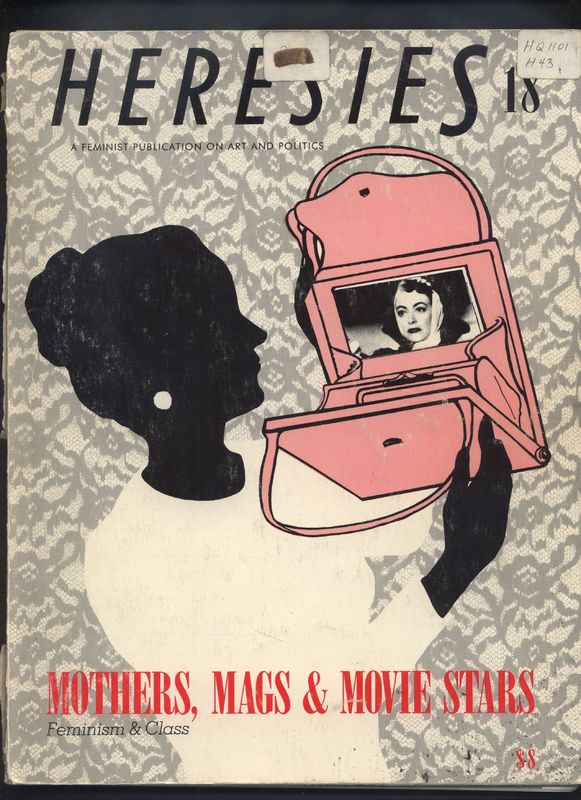

Cover of January 1986's Heresies.

Cover of Winter 1978's Heresies.

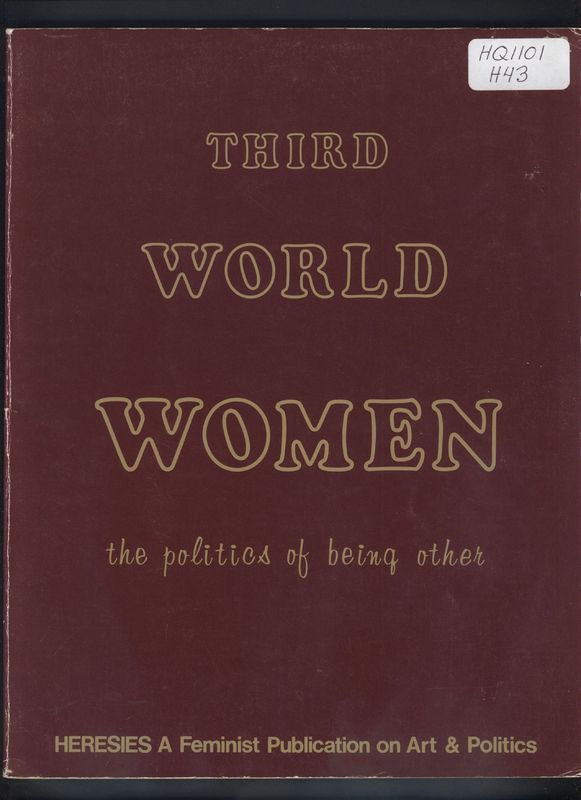

Cover of 1979's Heresies.

Front Cover of June 1982's Heresies.

The Heresies Collective

Heresies magazine exemplifies feminist ideology. The New York-based magazine focused on feminism in art and politics. Running from 1977 to 1993, they published 27 issues in total, each addressing a different topic related to women's lives and interests. As of December 2017, the University of Victoria's Special Collections has 21 of the 27 issues. A Mother Collective decided on a topic and recruited an issue-specific collective that could properly address that topic. This approach accounts for the vast differences in style, formatting, layout and tone throughout the magazine, but also reflects their ideology overall. Feminists embraced collectives for their equality and their rejection of patriarchy. Their philosophy on collaboration suggests that no voice is more important than any other voice; everyone matters and deserves to be heard. The fact that they chose to have each issue compiled by a different collective repeats this notion that all voices should be heard, as well as allowing for traditionally marginalized voices to be privileged, like in their "Lesbian Arts and Artists" issue from Fall 1977 or their "Racism is the Issue" issue from 1982. By having different issues specific to different topics, Heresies diversified their contributors.

The Mother Collective was, unfortunately, overwhelmingly white, a problem that some women of colour pointed out to them. The "Third World Women" issue, published in 1979, foregrounded the lack of racial diversity within the Mother Collective: "That [Third World Women's issue] was apparently a very difficult issue and the word that got back to me [Sue Heinemann] from Black feminists was the Heresies Collective is a group of racist white women" (Editorial Statement, "Racism is the Issue" inside cover). This predominance of white women in the Mother Collective persisted despite the Editorial Collective from the "Third World Women" issue drawing attention to this lack of diversity. The unfortunate truth was "that in 1979 (and for the most of the periodical's life) the mother collective was comprised exclusively of white women" (Meagher n.p.). Though they attempted to address the issue of race in their "Racism is the Issue" magazine issue three years later, this lack of racially diverse representation within the Mother Collective remains a regrettable oversight that at times undermines Heresies' claims of valuing all women and seeking universal equality. Later generations critique mainstream Second Wave Feminism for its failure to advocate for women of colour, and Heresies regrettably falls into this category, but at least it acknowledges that.

I position Heresies as being a part of Second Wave feminism and what Trysh Travis identifies as the Women in Print Movement, which she defines thus:

"Women in Print Movement, a group of late-twentieth-century 'book women' whose labor in the realm of print production was intimately connected to their analysis of how gender and power shaped 'the little world of the book.' A product of Second Wave feminism, the Women in Print Movement was an attempt by a group of allied practitioners to create an alternative communications circuit—a woman-centered network of readers and writers, editors, printers, publishers, distributors, and retailers through which ideas, objects, and practices flowed in a continuous and dynamic loop. The movement's largest goals were nothing short of revolutionary: it aimed to capture women's experiences and insights in durable—even beautiful—printed forms through a communications network free from patriarchal and capitalist control. By doing so, participants believed they would not only create a space of freedom for women, but would also and ultimately change the dominant world outside that space." (276)

These women attempted to break away from masculine methods and structures, carving a place for themselves that reflected their feminist values. Heresies and the "Women's Pages" issue illustrates the various methods of formatting and style that the women in this movement valorized. I use the Oxford English Dictionary's definition of format as "a style or manner of arrangement or presentation; a mode of procedure" ("format, n."). I use it broadly to think about how the page looks overall, including placement of photos, choice of medium and style of layout. Through their reuse of traditionally feminine techniques of collage and pastiche, their empowering use of humour and satire, their valuing of collectivity as well as multi-vocal inclusivity, Heresies communicates its departure from the mainstream into "new linguistic spaces for women" (Davidson 16).

The "Women's Pages" issue in UVic's Special Collections

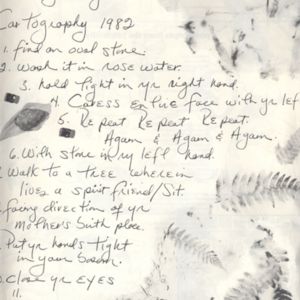

This page focuses primarily on the fourteenth issue, published in June of 1982, referred to as "The Women's Pages," which is dedicated to publishing page art by women who never before had been published in previous Heresies issues. They define page art as "a work of art made for a specific page and specific context, ideally to communicate a specific idea" (Heresies Collective "The Women's Pages" 2). I was drawn to this issue in particular for a couple reasons. Firstly, I found it to be the most intriguing because of the various media used to make this page art. Further, the copy in the University of Victoria's Special Collections had marginalia on the top of the cover. I knew this marginalia meant that this copy was unique and it showed proof of the readers' reactions to it, giving me a little more insight into its reception.

"Each of us worked on every page of this magazine."

("Feminism, Art, and Politics" 3)

Collectivity

The emphasis on collectivity plays a key role in Heresies' feminist approach. With Second Wave feminism and the Women in Print Movement, collectives appeared as a response to "widespread criticism of hierarchical organizations and their role in reproducing a patriarchal system" (Farrell 40). Collectives functioned as egalitarian, democratic systems that countered any implicit suggestions that some voices are more important than others, as hierarchies do. By modelling a new structure for working together, Heresies established “organizational cultures that would provide women with real alternatives to patriarchal structures based in hierarchy and domination" (Meagher n.p.). The Heresies Collective attempted to reflect their desire for equality through their collective approach to publishing as well as the magazine's content. Feminist publications like Heresies "helped shape those [feminist] ideologies and issues of the growing movement" (Flannery 29). Magazines allowed women to share and spread their thinking, and this means of communicating feminist ideology propelled the feminist movement. Heresies and other similar magazines allowed for feminists to develop their political beliefs, both as writers and as readers. Since the Heresies Collective would find contributors through posting ads throughout the country, the magazine was able to bring together women from all over to produce a magazine together, as described in Joan Braderman's 2009 documentary interviewing members of the Mother Collective (The Heretics). They forefront their focus on collaboration throughout their seventeen years of publishing.

Right from the editorial statement of the first issue, the Heresies Collective asserts its focus on collaborations, claiming, "Each of us worked on every page of this magazine" ("Feminism, Art, and Politics" 3). Members of the Heresies Collective emphasize how the collaborative work affirmed their hope in the feminism. Lucy Lippard claims, "Working with Heresies has solidified my beliefs in the whole women's movement. It's a collective of 20 people and it works beautifully so far" (qtd. in Meager n. p.). This publication of these magazines proved that women could work together and create something great without the need for male involvement or validation. Members of the collective see even this as a minor victory for women. Miriam Schapiro celebrates the collaborative process, saying, "There's an openness, a trust, there's an understanding that we can do it, that we are doing it, that we'll succeed in our relationships" (qtd. in Meager n. p.). Schapiro highlights the interpersonal experiences as key.

The experience of producing something together was just as important as the final product, which is why "the space reserved for editorial commentary was used by contributors to reflect upon the experience of producing the issue" (Meagher n.p.). This choice for the editorial space reflects the importance of the process of working together and learning from one another. The focus on the act of compiling the magazine over the finished product perhaps explains why the issues were rarely published on time. While subscription forms from the first issue promised four issues a year for $10, never in its seventeen years did the Heresies Collective actually achieve this goal (Meagher n. p.). Publishing an issue for the sake of fulfilling their original expectation did not warrant publishing an issue that did not fulfill their vision. They chose to perfect the issue rather than hastily finish it in order to publish it in time. In this way, Heresies rejected capitalist structures that demand consistent fulfillment of quotas reflecting Trysh Travis's description of the Women in Print movement as being "free from patriarchal or capitalist control" (276). This magazine was clearly not interested in turning a profit; instead it aimed to forge bonds between women and to share ideas and art.

The Handmade: Collage, Pastiche, and Rough-and-Ready

Collage reflects the collaborative editorial process through its aim of bringing together images or text from various different origins to make a cohesive piece of art. This method reflects Heresies' own organizational structure. The editors of the "Mothers, Mags and Movie Stars" issue write, "Our editorial process was like a collaged memoir...These discussions were somewhere between a sewing circle and a study group" (Heresies Collective 3). This comparison to sewing circles draws attention to collage's perceived feminine, unprofessional history. One does not need specialty tools or artistic education to partake in collage and for this reason collage has often been a feminine mode practiced as a hobby for women. Heresies' own Melissa Meyer and Miriam Shapiro coin the term "femmage" in the "Traditional Arts" issue, defining it as "a word invented by us to include all the above activities [collage, assemblage, découpage, photomontage] as they were practiced by women using traditional women's techniques to achieve their art -- sewing, piecing, hooking, cutting, appliquéing, cooking and the like -- activities also engaged in by men but assigned in history to women" (67). Meyer and Shapiro highlighted the double standard of collage's history as a women's art going unnoticed until Picasso and Braque "are credited with inventing it" in the early 20th Century (67). Feminist zines reclaim collage's origin as a feminine art. Heresies' "Women's Pages" issue from 1979 abounds with collage and pastiche, reflecting their aim to create a feminist style. The Collective attempt to find an art form to appropriately express their experiences: "women are finding ways to unbind their voices, rejecting patriarchal restrictive modes of writing in favor of the freedom of autobiographical, bricolage style writing and creating” (Davidson 15). Collage and pastiche allow free, unrestricted expression, accessible to all women.

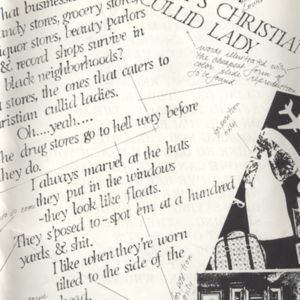

Another way that Heresies emphasized the importance of individual voices was through their publishing of art that appeared handmade or D.I.Y. Often these intersect with collage and pastiche, which frequently look as though they are handmade. Trysh Travis identifies the abundance of "rough-and-ready publications" produced by the Women in Print Movement (278). The women involved in this movement re-imagined what a finished product looks like. For example, on page 7 of the "Women's Pages" issue, Faith Ringgold's "I Love My Mother" writing retains Michelle Wallace's editorial notes. Through this choice to keep the notes rather than re-writing it, integrating the changes, Ringgold provides insight into the process of creation and collaboration, giving credit to her editor and drawing attention to how her writing evolves. Similarly, Janet Olivia Henry's "Coming Soon, Daisy's Christian Cullid Lady" looks as though it is still a work in progress with its handwritten "photo to come" comments in the background. Like "I Love My Mother," it draws attention to the process of producing artworks and magazines themselves, but also hints that the work itself is ongoing. Since Henry's work tackles the subject of racism and poverty in black neighbourhoods, the incompletion of the work presents this issue as yet to be resolved. Like "Coming Soon, Daisy's Christian Cullid Lady" itself, to combat systemic racial inequality there remains extensive work to be done.

The D.I.Y., unprofessional style of art featured in Heresies challenged the hegemonic expectations of magazines and art: “D.I.Y is also a form of progressive culture. Progressive culture, according to Walter Benjamin, is that which has the ability to transform the bourgeois properties and means of culture production” (Davidson 40). Walter Benjamin was a cultural critic and philosopher active in the early 20th Century, who critiqued the effects of mechanical reproduction on art in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Heresies understood the value of the handmade and Walter Benjamin's disdain for machine reproduction. They quote The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction right before their collective statement in the "Women's Pages" issue: "When the age of mechanical reproduction separated art from its basis in cult, the semblance of its autonomy disappeared forever" (qtd. in Heresies Collective 2). In valorizing D.I.Y., Heresies aligns itself with a counter-cultural movement that questions what our society deems valuable. Instead of focusing on a sleek finished product, D.I.Y. draws attention to the artist's process of the work of art.

D.I.Y. and handmade art emphasizes the individual who created the art and gives a voice to those who might have been traditionally disenfranchised. D.I.Y. does not require extensive training or money, so anyone can participate. The act of publishing the unpolished or inexperienced artists responds "to a society which marginalizes and silences a vast majority of young women that are not white, straight, able bodied or have a limited range of pop culture interests" (Davidson 42). In publishing this work as is, Heresies and the artists who publish such work "reject the authority of hegemonic culture which deems their lives unimportant" (42). They challenge the idea that white men's work deserves recognition above work by women, especially women of colour. The women who society and the media taught were not worthy of publishing and celebrating were given a chance in Heresies to tell their story: "Women are radicalizing this traditional form of writing by making them public, deeming their ordinary, everyday lives interesting and valid. Publishing diary-style writing is radical in that it extols the every person in a world saturated with celebrities, levelling the hierarchy of the importance of the mundane" (40). The publication of intimate, or even unfinished-looking art is a political act, suggesting the importance of every person's story and the equality of all. This interest in individuals' voices mirrors Consciousness Raising groups, popular in the 1970s. The Heresies Collective valued CR groups as a way for women to share their thoughts and experiences (The Heretics). The magazine's focus on women telling their own stories reflects these CR groups, which provided a space for "sharing and exploring each other's everyday realities" (Davidson 40). Heresies places women who the media usually overlook at the forefront of their magazine, asserting their opposition to mainstream culture's erasure of traditionally marginalized voices.

Since Heresies strayed away from appealing to mainstream ideas and popular culture, it was not a money-maker. Heresies relied on funding and grants from the government and arts councils to keep their magazine running (The Heretics). This lack of money could also explain the sometimes un-polished look of the magazine, as most "chronically underfunded" feminist periodicals like Heresies ran "without the expertise of paid permanent staff and relied upon volunteers (Meager n.p.). A polished, expensive look was less important than thought-provoking, intelligent dialogue and art. At the same time however, Heresies' reliance on funding and grants suggests that the magazine was perhaps too progressive for the general public. Most people were not ready for Heresies' radical ideas. The marginalia calling Heresies a "dike magazine" proves that, for some, women seeking independence and equality was threatening and discomforting.

"Telling one's own story has a feminist legacy."

(Davidson 40)

Valuing Individual Voices

Pages two and three of the first issue, "Feminism, Art, and Politics" from January 1977, provide a space where each woman in the Heresies Collective can write her own editorial statement revealing her own vision for the magazine and her perspective on feminism. They are not forced to distil their ideas to what they can all agree on; instead, this format celebrates individuality and disagreement. The women from the Heresies Collective remember the process of producing Heresies as being at times rife with conflict. Moira Roth recalls how often editorial collectives led to "rifts, anger, and profound disagreements" (84). The dissent between members, however, was encouraged; the Collective did "not expect one another to exist in one uniform category... this desire to imagine "feminism" as infinitely diverse was fundamental to Heresies" (Meagher n.p.). Members of the Collective remember these disagreements as positive, though. While they often had arguments that went long into the night and at times got heated, they remember that no one ever walked out (The Heretics). The Collective was committed to productive dialogue and the women would try not to take disagreements personally, understanding and respecting the importance of communication. By committing space in the magazine for the women to express their individuality, the women in the Heresies Collective communicate their ideology. These individual statements come after a collective statement on the inside cover. This layout reflects Heresies’ values: unity is ideal, but should not come at the cost of silencing voices.

Humour and satire

The "Women's Pages" cover borrows from the conventionally masculine newspaper format, which I would argue was chosen to satirize masculine format. This cover presents an alternative to newspapers that ignore women's issues. In using the masculine format, Heresies encourages readers to imagine a different culture that actually values women's experiences and news stories that feature women. They also sneak in humorous comments addressing the current climate for women, like in a weather report near the title, promising "no silver lining" tomorrow.

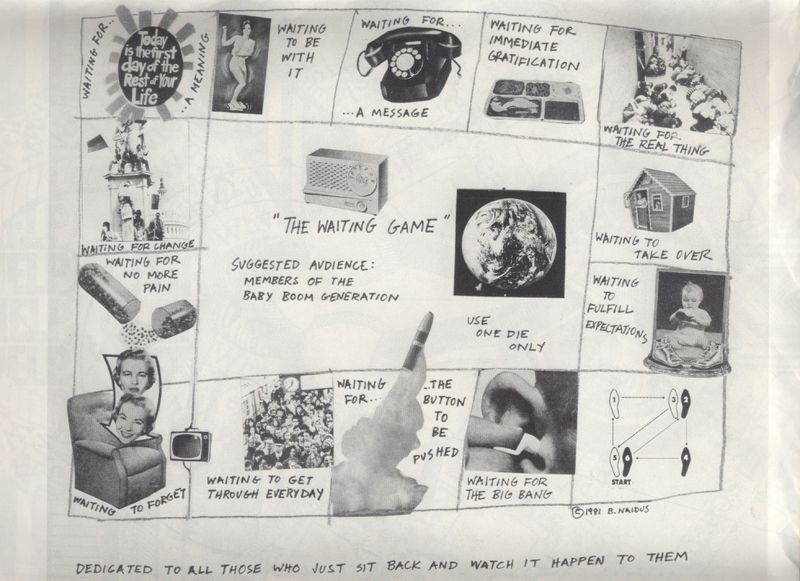

Beverly Naidus's "The Waiting Game" illustrates how humour can be used to communicate political disdain. Her mock board game targets members of the Baby Boomer generation that "just sit back and watch it happen to them" (23). Naidus draws attention to those who fail to make an effort to create change through her use of humour and satire to convey her message.

Tonya Davidson argues that humour in feminist zines works in a few ways. Firstly, the use of humour "attacks the humourless feminist motif" (56). Feminism can be light-hearted and fun. Further, Davidson suggests that in our society "men are controlling what is funny" (53). Women are often considered to be unfunny because men are the ones who decide what is funny and what is not. However, in feminist publications, "men's laughter is not required as validation" (54). Humour actually empowers women.

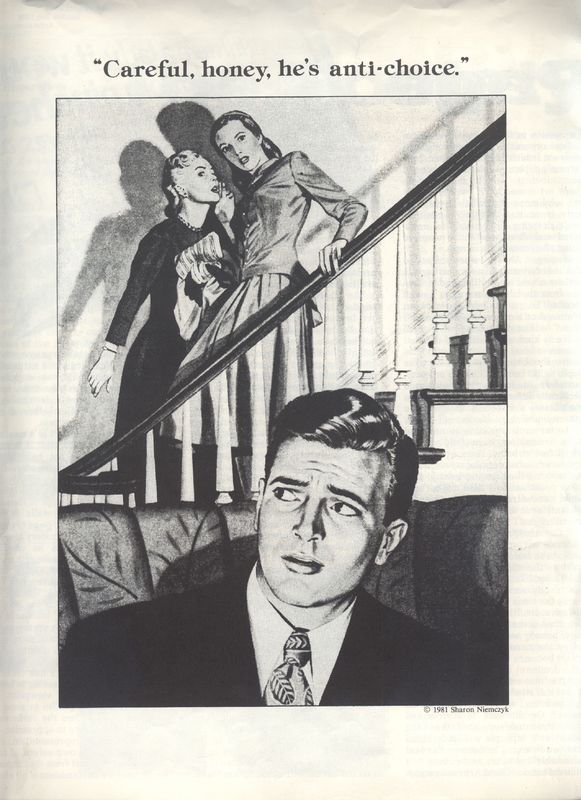

Often, feminist publications and zines repurpose old media to satirize what they see as out-dated ways of thinking. Tonya Davidson identifies zines' use of irony through detournement, which literally means "turning around" (44). Often, detournement alters old advertisements with the aim of "satirizing a consumer culture that constantly targets women" (45). Heresies uses this method through the piece titled "Careful honey, he's anti-choice" by Sharon Niemczyk. Using an illustration from an advertisement for a deodorizing soap that looks like it was probably from the 1950s, Niemczyk added a different caption to change the photograph's meaning. In doing so, Niemczyk aligns anti-abortion politics with old-fashioned, out-dated ideas. This page repurposes patriarchal material for feminist ends, taking the power away from the sexist ideology that produced the original photograph in the first place.

Inviting reader collaboration

The editors of the "Women's Pages" issue left page sixteen completely blank, indicating in the table of contents that this space was left for readers to contribute their own art to the magazine. In the editorial statement, they write, "We've included a blank page in this issue. We had two ideas about it. First, we thought it would be great if women made their own page art on it and sent it to us, both as feedback on the work in the issue and for possible inclusion in future issues... Then we realized it could also serve as a way of literally inserting one's own art into the magazine, seeing one's own work in the media. Once that's been done, every issue of Heresies #14 [the "Women's Pages" issue] ironically becomes a unique item- through the mass-reproductive process" (Heresies Collective 3). Through the inclusion of this blank page, the magazine broadens the collaboration beyond the artists actually printed in the issue. The Heresies Collective welcomes anyone to contribute. This invitation of readers' collaboration reflects Heresies' hope to include all voices, but also seeks to empower readers through "turning readers into writers, consumers into producers" (Davidson 49). Readers who use this blank page for their own art leave the passivity of simply reading the magazine and enter the realm of creation, positioning themselves as active members in the feminist movement.

Marginalia

This invitation to contribute to the magazine recalls the marginalia on the front cover. The copy in UVic's Special Collections had always been at UVic, as proven by the "Received June 3 1982, McPherson Library, University of Victoria" stamp on the cover, so the marginalia was most likely by a UVic student. The first comment says, "DIKE Magazine" above the title. Someone else has then added a response, reading, "PISS OFF! (ANYWAY, DON'T YOU KNOW DYKE IS THE NAME OF A GREEK GODDESS YOU JERK)." The second commenter is almost certainly referring to the goddess of justice, Dike, who frequently appears with Astraea, the goddess of innocence. However, the etymology of the word "dyke" or "dike" is unclear (Spears, "dike"). Regardless of whether the second commenter knew the obscure origin of the work "dyke," she seems to have found the connection to a Greek goddess to be empowering, since she uses it as a way of combatting the negativity of the first commenter's use of the word.

Marginalia fits perfectly with a magazine so focused on contribution from readers, the value of the handwritten and the importance of hearing all voices. While the Heresies Collective likely would not have appreciated the divisive, hateful tone of the "DIKE Magazine" comment, based on the ideology communicated by the format, layout and style of Heresies, the women likely would have celebrated the dialogue that the magazine started and the retort from the second commentator: "Piss off! (Anyway, don't you know that dyke is the name of a Greek goddess you jerk!)." The marginalia proves that the format and style of the magazine achieved its goal of inviting handwritten contribution from readers. Heresies successfully created a magazine that reflects feminist values of open dialogue and reader contribution.

Final Thoughts

The women of the Heresies Collective put out their final issue in 1993. They went on to continue the feminist ideology in their paintings, prints, films and writings, as shown in Joan Braderman's documentary honouring the women of Heresies called The Heretics. Heresies magazine provided a space for these women to share ideas, create community and explore their politics. With their focus on overturning capitalist, patriarchal hierarchies, Heresies modelled an organizational structure that centred on collaboration without ever sacrificing individuals' voices and experiences. The format and style they forefront in the "Women's Pages" issue mirrors their values and lives on through the zines that proliferated in the 1990s and continue to this day (Kempson 462). Heresies and other similar publications were key in spreading feminist ideology throughout the latter half of the 20th century and women today owe much gratitude to this generation of women who were not afraid to be heretical.

Want learn more?

Browse the archive of all the Heresies issues.

Joan Braderman made a documentary about the Heresies Collective called The Heretics, available for purchase at the film's website.

Check out other pages on late 20th Century magazines in UVic's Special Collections like Kick it Over and Rites Magazine.

An early 20th Century magazine for young women from a conservative, Evangelical perspective can be found in The Girl's Own Paper.

Examine Woman's World, a proto-feminist magazine edited by Oscar Wilde.

Discover other examples of marginalia in Frieda Hughes's copy of The Bell Jar and Robert Sward's copy of Sartre's Existentialism.

Works Cited

Benjamin, Walter. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. 1936. Translated by J. A. Underwood, Penguin, 2008.

"dike | dyke, n.3." OED Online, Oxford University Press, June 2017, www.oed.com/view/Entry/52709. Accessed 10 December 2017.

Davidson, Tonya Katherine. Feminist Zines : Cutting and Pasting a New Wave. Publisher not identified, 2005, http://hdl.handle.net/1828/795.

Farrell, Amy Erdman. Yours in Sisterhood: Ms. magazine and the promise of popular feminism. The University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

Flannery, Kathryn T. Feminist Literacies, 1968-75. University of Illinois Press, 2005.

"format, n." OED Online, Oxford University Press, June 2017, www.oed.com/view/Entry/73446. Accessed 11 December 2017.

Heresies Collective. "Feminism, Art, and Politics." Heresies, vol. 1, no. 1, 1977.

Heresies Collective. Heresies. Issue no. 1-2, 4-12, 16-18, 20-23, 25-27, 1977-1993. Special Collections, University of Victoria, HQ1101 H43.

Heresies Collective. "Movies, Mags, and Mothers." Heresies, vol. 5, no. 2, 1985.

Heresies Collective. "Third World Women." Heresies, vol 2, no. 4, 1978.

Heresies Collective. "Women's Pages." Heresies, vol. 4, no. 2, 1982.

The Heretics. Directed by Joan Braderman, Women Make Movies, 2009.

Kempson, Michelle. “‘My Version of Feminism’: Subjectivity, DIY and the Feminist Zine.” Social Movement Studies, vol. 14, no. 4, July 2015, pp. 459–72.

Meagher, Michelle. "'Difficult, Messy, Nasty and Sensational': Feminist collaboration on Heresies (1977-1993)." Feminist Media Studies, vol. 14, no. 4, 2014, pp. 578-592.

Meyer, Melissa and Miriam Shapiro. "Waste Not, Want Not: An Inquiry into what Women Saved and Assembled." Heresies, vol. 1, no. 4, 1978.

Naidus, Beverly. "The Waiting Game." Heresies. Published by Heresies Collective. Vol. 4, no. 2, 1982.

Roth, Moira. "The Tangled Skein: On re-reading Heresies." Heresies, vol 6., no. 4. 1989.

Spears, Richard A. “On the Etymology of Dike.” American Speech, vol. 60, no. 4, 1985, pp. 318–327.

Travis, Trysh. "The Women in Print Movement: History and Implications." Book History, vol. 11 no. 1, 2008, pp. 275-300.

T. G./Fall 2017