BLAST: review of the great English vortex. Volume 2: The War Number (1915)

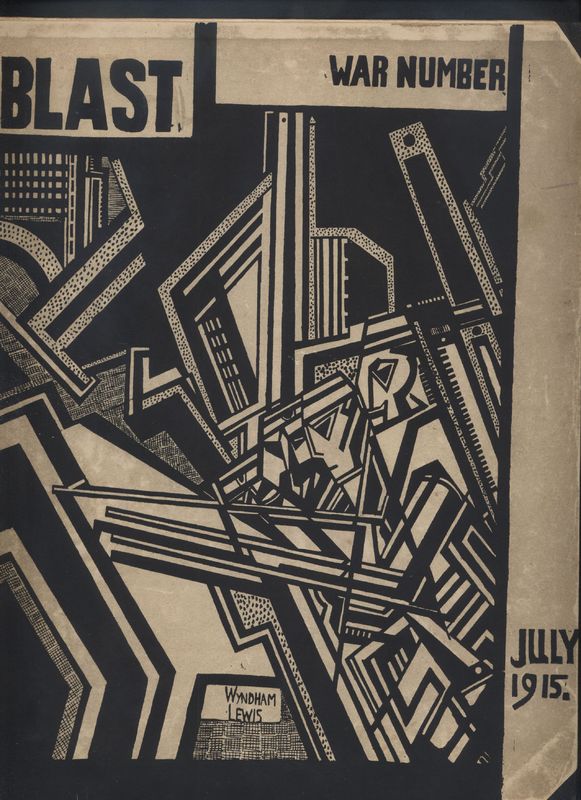

Cover of the War Number volume of BLAST: Review of the great English vortex.

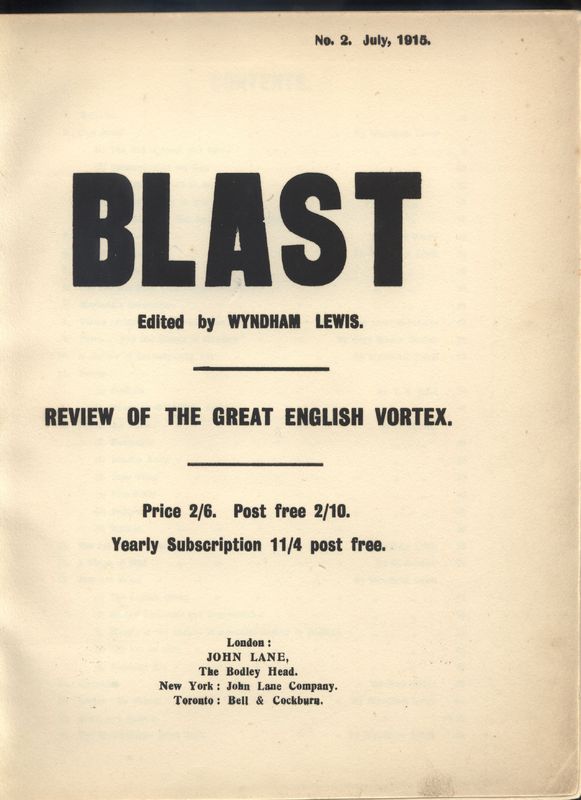

Frontispiece featuring a yearly subscription fee. BLAST was originally billed as a quarterly publication.

Progress and Absence: the Poverties of War

BLASTing into the Great War

BLAST is a publication of ambition, a material form of antagonism, and a manifesto of energy; BLAST is the magazine of Vorticism. BLAST 1 had flung Vorticism on the map as a burgeoning artistic movement, set on BLASTing the "Victorian Vampire" of the old world and BLESSing the "restless machines" of the modern world (Lewis 1). Editor Wyndham Lewis packed entire plays and chapters of books into a big pink magazine and waited for the crowds to cheer for another volume. Then, less than a month after the first volume of BLAST was published in July of 1914, the Austro-Hungarian Empire declared war on Serbia, and within six days most of Europe and the United Kingdom were locked into a deathmatch known as The Great War.

BLAST was originally billed as a quarterly publication, but with the the outbreak of war, editor Wyndham Lewis was in no position to push out a second volume for the Fall of 1914. Instead, it wasn't until July of 1915 that BLAST 2 was finally published. The issues leading to the publication were complex, as we'll see a little further down this page.

Glancing at the second volume of BLAST next to the first, the most striking difference is an absence: a lack of pink and a lack of paper. The writers and artists of Vorticism had been productive, and Wyndham Lewis was certainly enthusiastic about the magazine, but by July of 1915, a year saturated with industrial total war had taken its toll. There were ink shortages, a deficit of personnel, and dwindling capital (Leveridge 4). The Vorticists simply couldn't push out the material heft they had before. Instead of the pink monster of the previous year, BLAST's subscribers received a half-sized stack of papers, with a new paper and ink design depicting soldiers marching across the cover. On the upper-right hand corner of the cover were two words tolling the times: WAR NUMBER.

Make no mistake: the aggressive, interventionist spirit of BLAST marches proudly on through the War Number volume! In other ways, though, things had changed.

-------------------------------------

This page is focused on BLAST 2. For coverage of the pre-war landscape in the arts, BLAST 1, and Vorticist philosophy, visit last year's page here.

Wyndham Lewis's editorial introducing the War Number and its discontents.

This note to the public outlines promises for subsequent volumes of BLAST.

Mini-manifesto declaring the role of artists in the war.

Glaring at the Front: a New (Pre)Occupation

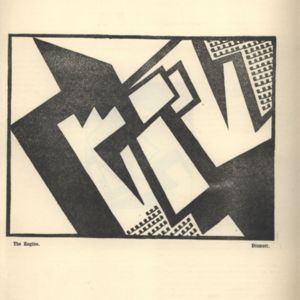

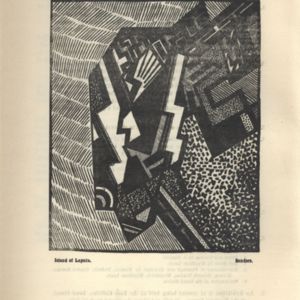

With the dawn of war a new subject matter for art was clearly on the horizon, and the Vorticists fixed their gaze on the Western front. Featured designs still contained all of the heavy ink and intense angularity of the first volume, and some of the ambiguity of the figures being represented, but the War Number focused everything on war. Gone were the full-length plays and stories of the first volume. Instead, the War Number throws biting criticisms of the world at-large next to fiery poems praising the grand machinery of it all.

Where Blast 1 places Italy (in lieu of F.T. Marinetti and the Futurist artists) in the crosshairs of critique, BLAST 2's editorial epitomizes the shift in critical gaze from Italy to Germany. Lewis writes, "the essential German will get to Paris, to the Cafe de la Paix, at all costs" (Lewis 2 p. 6). Lewis proclaimed himself cognizant of a German obsession with conflict and dominance that he himself embodies. Lewis admitted that Vorticism has intellectually inherited much of the German work in abstraction and machinery as subject in the arts. In this way, Vorticism seeks to pull back from the boundless nationalism of the time, while retaining the notion that as a movement it is uniquely English. Lewis always situated himself somewhere in the middle of conflict. His editorial starts with the claim: "BLAST finds itself surrounded by a multitude of other blasts of all sizes and descriptions" (Lewis 2 p. 5). It's as though Lewis placed his magazine on an even playing field with the bombs and bullets that actually ended lives and mangled bodies. It's as though Lewis saw his own activities as an artist as equally important to the activities of soldiers. More precisely, he saw himself as a soldier in an art-war.

As far the physical war goes, he promised in a "Notice to the Public" that the third issue of BLAST will feature notes of his own from the front. While he did eventually serve as a gunner in the Royal Artillery and as a commissioned war artist for the Canadian army, Lewis was one of the last Vorticists to sign up, and he never published those notes from the front in another issue of BLAST (Meyers 79). As a matter of fact, no third issue was ever published. The war would see many promises abandoned.

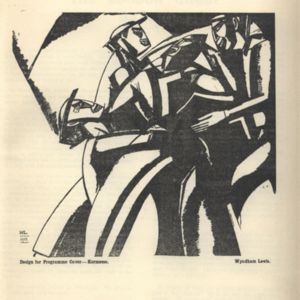

Below are four illustrations of war scenes, all but the last done in the classic Vorticist style of hard lines carving aggressive scenes into abstraction. The first two are ink illustrations by Lewis, which were studies for paintings that were already exhibited to the public. So, why do studies for paintings appear in BLAST after the finished paintings were already released? Would the magazine not be more appealing (and Vorticist in principle) if it only featured new illustrations?

There are two important factors here. Lewis was struggling to get the War Number finished and published. The volume of artworks that he had to select from was dwindling as an increasing number of Vorticists shipped out to the front. He may just not have had the option to feature new work.

The other reason, however, is the idea that the appearance of studies in the magazine may have enticed the public to actually visit the galleries in London where the paintings were being exhibited. Putting ink sketches of a painting in your magazine is a way of getting free advertising for the actual paintings. It's an economic strategy, a perfect solution for an art movement that was starving in war.

Table of contents featuring Wyndham Lewis, Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, Ford Madox Heuffer, J. Dismore, H. Sanders.

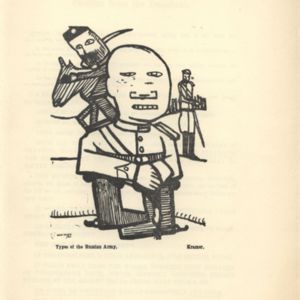

List of designs and designers featuring Dismorr, Etchells, Gaudier-Brzeska, Kramer, Nevinson, Roberts, Sanders, Shakespeare, Wadsworth, and Wyndham Lewis.

Squad of Theseus: a Changing Cast of Characters

With the mobilization of a nation at war, people of all backgrounds were called on to set aside their peacetime occupations and repurpose their production potential for the war effort. Many of the artists and writers who appeared in the first volume of BLAST were either sent to the front lines in France or otherwise affected by mass mobilization. Several contributing artists and writers from the first issue of BLAST are therefore absent from the War Issue, and several new hands took their places. Painter Spencer Gore had died from pneumonia before the first volume was released. Sculptor Jacob Epstein was drifting away from the Vorticists. Increasingly open anti-semitism on Lewis and especially Pound's part may have had a less than gentle hand in this. Illustrator Cuthbert Hamilton had been conscripted into the army as a Special Constable. The war dispersed the artists, but it also raised questions as to whether or not movements like Vorticism were complicit in starting the war in the first place. There is reason to believe that other London artists may have contributed to BLAST 2, but that they may have been apprehensive about the reputation that such an association would have attached to them. Therefore, BLAST 2 included the work of a much smaller group of people, but some of them, finally, were women.

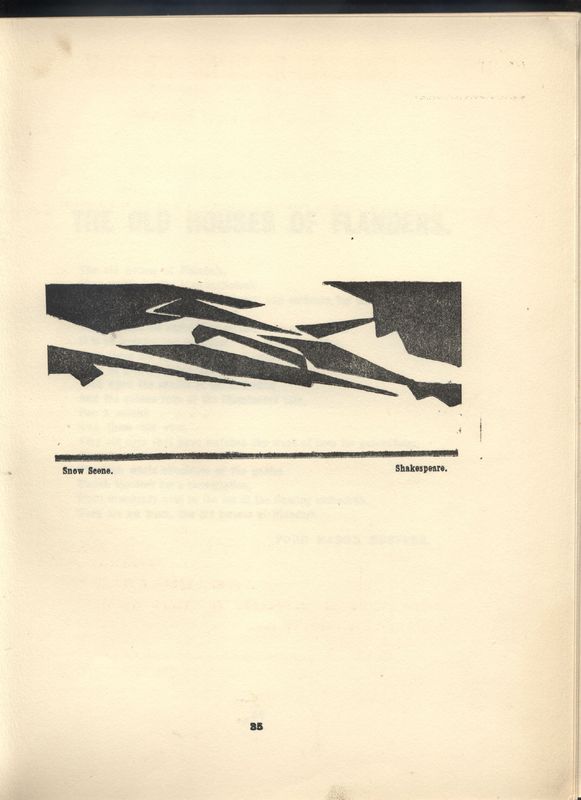

Misogyny is a glaring undercurrent of Vorticistm. The first issue's letter "To Suffragettes" patronizes women, instructing them to "leave works of art alone. You might some day destroy a good picture by accident" (Lewis vol. 1 p. 151). Despite the problematic masculine tone of BLAST, the War Number definitely saw the rise of women in Vorticism. Like many spheres of homefront production, women rose to take the roles men left vacant when they shipped out to France. Jessica Dismorr and Helen Sanders were signatories to the first BLAST's manifesto (an essay outlining the charges and aims of Vorticism), but in the War Issue, these women marched into contributing roles as both artists and writers. In this way, Dismorr and Sanders were like reserve artistic forces who assumed active duty roles when the previous artist-soldiers could not fulfill their duties to the front of artistic production. They waited behind the front line for their compatriots to become inactive, then took their places with new fervor. The War Number issue also contains the first appearance of art by Dorothy Shakespeare, Ezra Pound's wife. Her "Snow Scene" is further discussed in the "Sex and Death" section below.

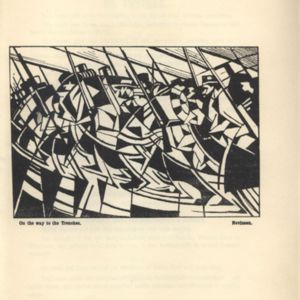

Featured directly below is "On the way to the Trenches," a cleverly named charcoal study for Nevinson's painting "Back to the Trenches," which premiered in London in 1914. Note the juxtaposition of long thin lines with thick black shapes set on top of glaring white space, which come together to form hard, swift, angular figures. The bearded soldier on the right is evidence that it is a French unit depicted, as the English were made to shave their faces to fit uniform. The aesthetics of Vorticism bear a strong debt to those of Futurism. Why wouldn't the Vorticists just call themselves Futurists and meld together as part of a larger movement? Well, the difference between the movements was chiefly political. Wyndham Lewis saw Vorticism as a uniquely English response to Cubism, untied to Marinetti's Futurism. Nevinson, however, continued to solidify his relationship with Marinetti, which led Nevinson and Lewis to break ties, leaving the Vorticist group with only a final illustration (below).

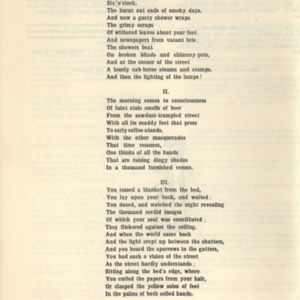

Another change in contributing staff for BLAST 2 came in the form of midWestern American poet who had newly arrived in London to begin his literary career. That contributing member was Thomas Stearns Eliot, and his poignant "Preludes" and "Rhapsody on a Windy Night" are featured in the gallery.

If most of the contributing members of a movement-magazine are absent from a subsequent volume of the magazine, is it still the same magazine? Lewis certainly thought so. In his 1939 memoir, Blasting and Bombardiering, Lewis explicitly states that Vorticism is and always was, at the end of the day, whatever he felt like it was on that particular day of week (Blasting and Bombardiering 34).

Color and Paper: Difference and Materiality

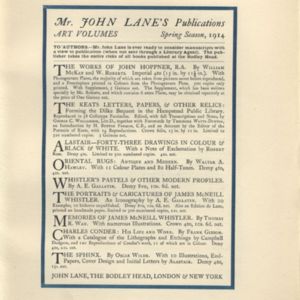

After July of 1914, a plethora of materials were requisitioned, repurposed, or otherwise made unavailable to the public due to the war. This was detrimental for the availability of art materials. In the early 20th century, the majority of England's dyes were imported from Germany (Clapp 133). After an Englishman, William Henry Perkin, invented artificial dyes in 1856, German industry rapidly developed and by 1914, Germany produced four times as much dye as England (134). Once the war was underway, trade embargoes with Germany made English industrial consumers of these dyes hard-pressed for color (134). Materials like fabrics became visually duller as prices of imported dye skyrocketed (134). With Lewis already struggling financially, outrageous dye prices in London made printing the heavy puce-colored cover of BLAST 1 impossible for BLAST 2 (Leveridge 7). Instead, Lewis created the illustration shown at the top of this page for the cover. Also, the publisher's advertisements in BLAST 1 were locked in by a brilliant blue border, but in BLAST 2 the costly blue was abandoned for a cheap black. Thus, poverty of color proves to be yet another way in which art is starved by war.

It wasn't just the colors that were impoverished. The stack of paper itself in BLAST 2 is thin compared to BLAST 1. The sheer number of pages is reduced from 158 in the first issue to 102 in the second, and the weight and size of the book clearly tells this difference. Furthermore, while BLAST 1 only had seven blank pages, BLAST 2 has seventeen. Even the list of blasts and blesses had dropped from seventeen pages total in the first issue to one page of blesses and one of blasts in the second. To make up for the lack of new artwork in the War Issue, essays by Lewis and poems by Pound run across the the bulk of the pages. As much as Lewis wanted and needed to get the second issue, the economic steam behind Vorticism was waning, and all but the most diehard Vorticists were disappearing, one after another.

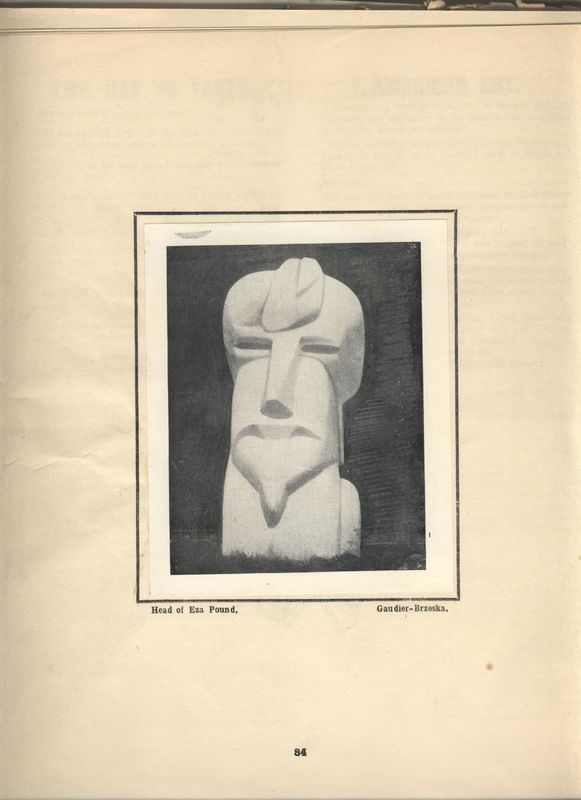

Head of Eza Pound (pasted-in photogravure of Gaudier-Brzeska's sculpture) in two different copies from (likely) the same print run. Note the mispelling of "Ezra" and the sliver of a fingerprint on each copy.

"Vortex (From the Trenches)" by Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. The second page contains the death notice, "MORT POUR LA PATRIE."

Snow Scene by Dorothy Shakespeare.

Sex and Death: Henri Gaudier-Brzeska

In 1910, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska (aged 21) moved from Orléans, France to London to become an artist. Almost immediately, he met Lewis and Pound and became a founding member of the London Group and later Vorticism (Jameson 32). At the advent of war in 1914, Gaudier-Brzeska enlisted with the French army and was sent to the front (35). Before joining his French compatriots in the trenches, however, Henri Gaudier Brzeska was commissioned to sculpt a bust of Ezra Pound (35). The sculpture takes unmistakable influence from Hoa Hakananai'a, the mo'ai sculpture stolen from Rapa Nui (Easter Island). During Gaudier-Brzeska's time in London, Hoa Hakananai'a stood outside the gates of the British Museum, a shining example of British acquisition through empire (Brooker 12). The sculpture also has an obviously phallic quality (especially from the back). This appears to be both a product of Gaudier-Brzeska's desire to "derive emotions solely from the arrangement of surfaces," in accordance with vogue Freudian thought, as well as an attempt to capture the masculinity of the figure of the model and commissioner, Ezra Pound. The image of Guadier-Brzeska's sculpture (photogravure) is the only image that was pasted on rather than printed into each original copy of the War Issue. Each original pasted image bears a little sliver of a thumbprint somewhere on the paper, likely an accidental mark of the printer's inky hand. This one is just to the right of the upper-left hand corner of the image.

Unfortunately, both original and reprinted copies of the magazine feature a misspelled title: "Head of Eza Pound." This overlooked mistake is likely a consequence of Lewis rushing to get the War Issue published.

As he fought for France, Gaudier-Brzeska kept up correspondence with Lewis from the trenches. In his "Vortex (From the Trenches)," Gaudier Brzeska speaks of the war as, "a paltry mechanism, which serves as a purge to over-numerous humanity" (BLAST vol. 2, 45). It was not an uncommon view at the time that European (and English) society was outdated, the population was excessive, and war would bring a more orderly future society by rooting out its weaker members. "Vortex" ends with a notice: "MORT POUR LA PATRIE. After months of fighting and two promotion for gallantry Henri Gaudier-Brzeska was killed at Neuville St. Vaast on June 5, 1915 (BLAST vol. 2, 45). Thus, a high level of unintended irony is achieved by Gaudier-Brzeska writing, "The war is a great remedy."

Gaudier-Brzeska wrote that the war "takes away from the masses numbers upon numbers of unimportant units, whose economic activities become noxious as the recent trade crises have shown us" (BLAST vol. 2, 45). Certain politicians and ideologues might have us believe that an artist, like Gaudier Brzeska, is one of these "unimportant units." It is of paramount importance that we acknowledge, no matter how much an artist may exalt war, that the physical destruction of war ultimately creates a grand absence in art. Only after the vortex of war will something new be allowed to emerge.

Dorothy Shakespeare's illustration, Snow Scene, appears on the page opposite Guadier-Brzeska's death note, giving the reader a visual sense of the stillness of death in the middle of a Vortex.

Want more?

Bless you! The University of Victoria has a plethora of Vorticist books and fronds!

For University of Victoria's original copies of BLAST 2, see: Special Collections, University of Victoria, call number: PR6023 E97Z6129 no. 2

Learn the story of C.J. Fox, the man who donated most of UVic's Lewis materials, including BLAST 2, click here

For a webpage of UVic publications on Lewis in the greater context of Modernism, click here

For UVic Special Collections, click here

ALSO! For more on Wyndham Lewis and the Vorticist movement, take a look at some of the works cited and consulted for this page below.

Works Cited

Clapp, Edwin J. Economic Aspects of War. New Haven. Yale University Press. 1915.

Jameson, Frederic. Fables of Aggression: Wyndham Lewis, the Modernist as Fascist. Berkeley. University of California Press. 1979.

Leveridge, Michael E. "Printing BLAST," Wynham Lewis Annual. Vol. 7. 2000.

Lewis, Wyndham, editor. BLAST: Review of the great English vortex. No. 2. London. John Lane, the Bodley Head. 1915. UVic Special Collections Call Number PR6023 E97Z6129 No. 2.

Lewis, Wyndham, editor. BLAST: Review of the great English vortex. No. 1. London. John Lane, The Bodley Head. 1915. UVic Special Collections Call Number PR6023 E97Z6129 No. 1.

Lewis, Wyndham. Blasting and Bombardiering. London. Arthur Press. 1937.

Meyers, Jeffrey. The Enemy: a Biography of Wyndham Lewis. London. Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd. 1980.

Work Consulted

R.R. Palmer, et al. History of the Modern World. 6th Edition, New York. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. 1983.

TF/Fall 2017