R. M. Ballantyne's The Cannibal Islands: Captain Cook's Adventures in the South Seas (1869)

Robert Michael Ballantyne

“Identified in the minds of his young followers with the bravest deeds performed by the manly characters in the fictional tales he wrote” - Eric Quayle

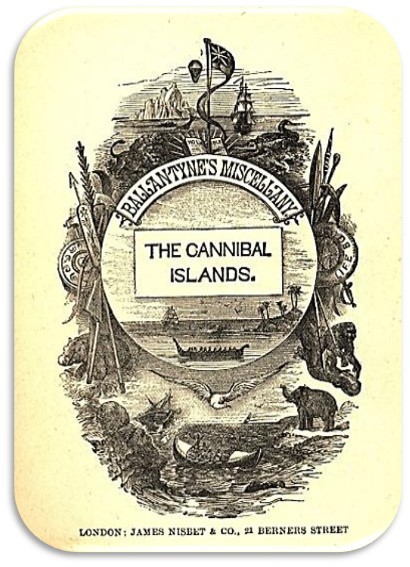

In 1869, Robert Michael Ballantyne, the beloved author of numerous boy's adventure stories, published ten books of his series Ballantyne's Miscellany. Capitalizing on the popularity of his previous books, Ballantyne intended these volumes to have an even more didactic slant than works of fiction like his most famous book, The Coral Island (1858). Volume IX of Ballantyne's Miscellany, entitled The Cannibal Islands, or, Captain Cook's Adventures in the South Seas, recounts the famed explorer's more intriguing encounters with the native islanders of Fiji, Tahiti, New Zealand, and Hawaii. Ballantyne uses a creative non-fiction style that reproduces the most sensational aspects of Cook's voyages, lending Cook's account a fictionalized perspective nearly a century after the ill-fated captain jotted his experiences in journals. Referencing these journals and those of the various naturalists, scientists, and missionaries who kept similar journals in the early days of South Pacific exploration, Ballantyne's book praises the British colonial regime, lauds the superiority of European technology and science, and expresses the necessity of impressing Christian morals upon the “heathens” of those barbaric islands. For a book intended to educate, The Cannibal Islands presents an extremely narrow view of these different Polynesian peoples, tarring them all with the same brush instead of depicting them as culturally distinct in their own right; in the first chapter, Ballantyne writes, “[these] savage races [are] so thoroughly addicted to the terrible practice of eating human flesh, that we have thought fit to adopt the other, and not less appropriate name of the Cannibal Isles” (12), setting a discriminatory and moralizing tone that bombards the reader from the first page to the last. Curiously, this racist and bloody text was considered appropriate reading for Victorian children; nestled discretely between such Miscellany titles as Saved By the Lifeboat; A Tale of Wreck and Rescue (1869) and Digging for Gold; Adventures in California (1869), The Cannibal Islands' explicitly gory scenarios are juxtaposed with the observations of disgusted British adventurers and are heavily embroidered with Christian moralizing. This essay seeks to closely examine a surviving copy of Ballantyne's book from the University of Victoria's Special Collections, and to demonstrate the connection between the book's history, religious instruction, and the Victorian fascination with civilizing “the naked savage . . . that poor creature” (44).

Ballantyne embodied the very attributes he gave the heroes of his myriad tales of adventure; he was handsome, adventurous, and spirited, with a sense of patriotic duty and a solid Protestant background. According to biographer Eric Quayle, the author “gained the distinction of being identified in the minds of his young followers with the bravest deeds performed by the manly characters in the fictional tales he wrote” (Ballantyne the Brave, 1). Born in 1825, he grew up in Edinburgh, the ninth of ten children in a financially unstable but otherwise happy household (2). At the young age of sixteen, Ballantyne became employed as a clerk for the Hudson's Bay Company and spent six years working in the Canadian wilderness; his first book, entitled Hudson's Bay, was an autobiographical account of his experiences, first published in 1848 (Quayle, First Editions, 15). As noted in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, it wasn't until 1856 that he published his first of over one hundred “books for boys,” Snowflakes and Sunbeams; or, The Young Fur Traders, thus “establishing a pattern for his career as author of boys' adventures set in authentic backgrounds” (Rennie). His works were influenced by many of his own travels and even after his wife Jeanie had six children, he travelled abroad with his family until they settled permanently in London in 1883. Although he never did venture to the exotic South Pacific, the site of several of his works, he drew from travel accounts and journals; however, he preferred to have first-hand knowledge of the situations he depicted, and “many of his later books were indeed based on personal research, which took him 12 miles off the Scottish coast to the Bell Rock for The Lighthouse (1865) and to the bottom of the Thames in a diving suit for Under the Waves (1876)” (Rennie). His heart failed while on vacation in Italy in 1894 (Rennie). In life, Ballantyne was himself an example of the adventurous, stalwart masculinity that he inscribed onto the protagonists of his numerous tales.

Frontispiece found in each book in Ballantyne's Miscellany

Over the Rocky Mountains cover (from the series Ballantyne's Miscellany)

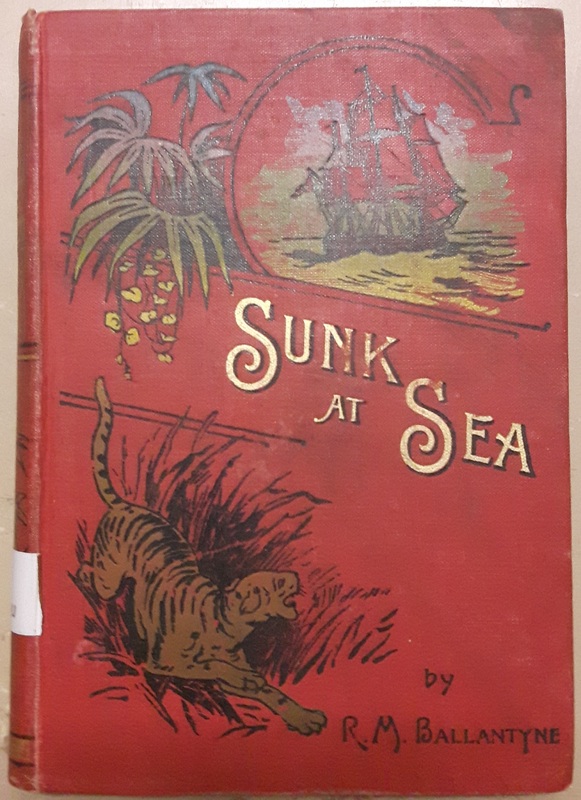

Sunk at Sea cover (from the series Ballantyne's Miscellany)

On Ballantyne's Miscellany

"Knowledge being cunningly imparted without the unsuspecting reader being aware of the educational benefit he was receiving" - Eric Quayle

A devout Presbyterian, Ballantyne's work reflected his commitment to his faith; at just twenty-four years old, the “regular church-goer” was elected to be “an elder of the Free Church of Scotland, his firm faith pervading his writing as well as his life” (Rennie). In 1863 he made an important alliance at a literary dinner, where he chanced to sit next to James Watson, the proprietor of James Nisbet & Company Publishing. This company was founded by James Nisbet, who also founded the Sunday School Union, which responded to the call for affordable moral texts for the Sunday school pupil (Ballantyne the Brave 161). Indeed, besides the books for boys Ballantyne and Watson published together until the author's death in 1894, James Nisbet & Company published mainly religious texts; one ad in the Times from 1870 shows Ballantyne's Miscellany sandwiched between such titles as “A Cheap Edition of the Shepherd and His Flock” and “Christ is the Word. by the Rev. Whitfield” (“Board and Residence”). Together they conceived the idea for a series of small, affordable books called Ballantyne's Miscellany. As Quayle elucidates,

The author visualized using these little volumes as a medium for instructing the poorer and less educated members of the community in what he considered to be religious truths, at the same time teaching them something of history, geography and science, but with the whole twisted into the thread of an adventure tale, the knowledge being cunningly imparted without the unsuspecting reader being aware of the educational benefit he was receiving. (161)

The first three volumes (Fighting the Whales, Away in the Wilderness, and Fast in the Ice) were published together in December of 1863. Although the books cost only a shilling apiece and The Coral Island had made Ballantyne a beloved household name, they were not immediately successful. Their target audience was not young boys as with his other works, but as Quayle suggests, “the Victorian working man,” whose desire to purchase such books might have been dampened by reviews like that of the Dean of Carlisle: “The writer appears to have attained the peculiar and rare excellence of so inter-weaving sound religious instruction with his narratives, as not to burden them with prosy observations, and yet never to lose sight of the manifest object which pervades the whole, to save souls” (Ballantyne the Brave 163). Ballantyne had sent out a holograph letter to “hundreds of church dignitaries, parish priests and curates, throughout the length of the British Isles,” requesting that they promote his works to poor adults, and hopeful that they might be suitable for the young as well (162). However, this avenue of promotion to the clergy and the poor, coupled with the drab exterior appearance of the cheap little books, excluded those who would be most apt to spend money on such a work: the middle classes and especially their children. Thus, the books were re-branded without references to the working class, with more colourful covers and a new introduction that “toned down [Ballantyne's] remarks about the Almighty, lest and intending purchaser should think that the religious bias was too strong” (165). Eventually, Ballantyne's Miscellany, with its religious and moral instruction, would grow to include eighteen volumes, often sold as a set that would be reprinted right up until the First World War (165). Although the volumes sold for only a shilling apiece, this series became one of Ballantyne's “most lucrative literary efforts” (165).

The Book Itself

Complications, Revelations, and Illustrations

The publishing history of the particular copy of The Cannibal Islands in UVIC's Special Collections is something of a mystery; as Quayle remarks, “Unravelling the bibliographical details and first edition dates of this series has been a long and complicated task, and without access to the author's letters and personal records it is doubtful if the problem could have been resolved with any degree of certainty” (First Editions 103).[1] Given Quayle's description of the appearance of the first edition (“Device on spine is a bow and quiver and crossed spears” (108)), it appears that the UVIC copy is not a first edition, but an even more obscurely documented later edition. There is an absence of information within the book itself: no suggestion as to the edition number, no date of publication, and no reference to either an editor or an illustrator.[2] However, the many advertisements in the back of the book mention all eighteen volumes of Ballantyne's Miscellany; as the final volume of the series was first published in 1886, it appears that this particular edition was produced thereafter. Moreover, it advertises the last book for boys published before Ballantyne's death, The Walrus Hunters (1893), which again suggests that the book was published following this date. However, the extensive advertisements (sixteen pages of ads!) make no mention of the posthumously published Ruben's Luck (1896), so it may be that this particular edition was produced sometime in the three year interval between these two books. No mention of the printers is made until the final page of Ballantyne's story: the line “Printed by T. And A. CONSTABLE, Printers to Her Majesty, at the Edinburgh University Press” (Ballantyne 120) serves as a nice reminder that the book is written and produced from a firmly British perspective.

The book itself is slightly smaller than a standard novel size, and with only 120 pages of text plus advertisements and endpapers, it is not very heavy; notably, these dimensions would make it easy for a boy to slip the book into his satchel and set out on an adventure of his own, unhindered by the book's size or weight. Bound in a vivid crimson cloth, the cover is very attractive. With coloured inks it depicts a ship at sea and some hanging tropical plants in blues and greens, and a ferocious tiger and some bamboo fronds on the spine in a burnt orange hue.[3] The cover's title is embossed in gold, as it is on the ornate spine, and on the back cover the printer's logo is embossed in black and encircled with flowers. The exotic look of the cover suggests that it is one of the editions that benefited from Ballantyne's re-branding, making it a more attractive purchase for the middle-class boy with a shilling to spend. The paper inside the book has yellowed with age and is not particularly noteworthy; it is of average thickness and, given the inexpensive price point of the book itself, it was probably cheap to print on. The typeface and layout of the book are clear and concise. The typeface is uncramped and of decent size, and the margins are wide, making the book easy to read. There is a frontispiece, an introduction, a table of contents, and eleven titled chapters. The chapters are followed by the sixteen pages of advertisements with favourable blurbs from various publications like The Times, The Athenaeum, and The Guardian. Interestingly, it seems that the first eight pages of ads were accidentally reprinted again, as the following eight pages are identical.

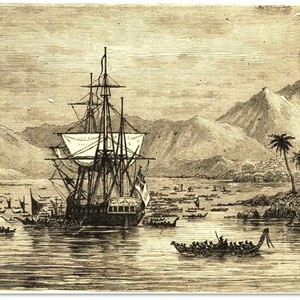

There are only three illustrations and a frontispiece in The Cannibal Islands, and there no maps, timelines, glossaries, or dedications. Again, this is probably due to Ballantyne's insistence that the books be sold very cheaply, thus saving on ink and paper. According to Bamber Gascoigne's How to Identify Prints, the closely ruled lines of the illustrations, “about five lines to the millimetre,” suggests a steel engraving (55g). He notes that “the more reliable sign of steel is in the lightness and delicacy of pale lines. . . steel engraved lines therefore retain clarity and firmness while being thinner and fainter than their counterparts in copper” (55h). Given this evidence, it appears that the three illustrations are likely steel engravings, and that the less minutely wrought but still high detailed frontispiece might have been done in copper. Each of the illustrations depicts a scenario at sea. The first is a distant image of Cook's ship Endeavour being met offshore by a war canoe full of indistinct islanders, and is entitled “New Zealand Canoe” (Ballantyne ii). The second, “Lagoon Island” appears later the book and is set at a similar distance, illustrating the whole of a ring-shaped island at sunset, with barely discernible people in canoes (36). “Cook Leaving Tahiti” is the third and final image, set at the same distance again, and depicts Cook's ship surrounded by tiny canoes, set against the hills and palm trees of the Polynesian island (92). The Ballantyne's Miscellany frontispiece is intriguing; it is shaped like a badge, with the book's title in the center, and made up of details that allude to other titles in the series, like a hot air balloon (Up in the Clouds), a life-preserver and oar (The Lifeboat), a pickaxe (Digging for Gold), an iceberg (Fast in the Ice), and a number of exotic animals. Of greatest interest to this essay are the open bible and Union Jack significantly emblazoned at the top of the badge, and the native canoe full of dark, indistinct figures in the turbulent sea at the bottom (Ballantyne iii). It is interesting to consider that for a book whose text so graphically juxtaposes the fantastic details of “heathen” life with the civilizing nature of British influence, the illustrator[4] has chosen to avoid any close depictions of the natives themselves or their interactions with the sailors, choosing instead to illustrate from a distance that renders the islanders minute black dots in canoes.

[1]Michael Sadleir also remarks on the difficulties of ascertaining information about this particular series (Sadleir 23-24). He lists four different editions, the last being in 1886. Sadly, none of the physical descriptions of his four editions match the UVIC copy and, as I will show, the book had to have been printed after 1893. The series does not appear at all in Robert Lee Wolff's Nineteenth-century Fiction: A Bibliographical Catalogued Based on the Collection Formed by Robert Lee Wolff.

[2]I had hoped that once I found the date of publication I might be able to track down who the editor and illustrator were, but alas, the details of my particular copy are extremely obscure, if not non-existent. Worldcat OCLC lists editions printed in 1869, 1874, 1881, 1883, 1886, 1893, and 1910, but also various stabs in the dark like “1880-1920?”. My book neither fits the description of the 1893 or 1910 editions, and as I will show, the others are irrelevant. I checked with the Toronto Public Library's Osborne Collection; it lists four copies, of which the 1898 edition could be a match given its date, but my correspondence with librarian Mary Bissell proved that this is not so (Bissell).

[3]I was struck by the tiger on the front of the cover, knowing that tigers have never lived in Polynesia. It seemed like a gimmick to entice young readers, until a few Google Image searches for Ballantyne's Miscellany revealed that the other books in the series from this edition have the same cover, but with differently coloured of cloth bindings. I clicked on every copy I could find that might give ANY information about this edition, but this tactic proved fruitless as well.

[4]There are no initials or signatures on any of the illustrations to indicate the name of the illustrator/s.

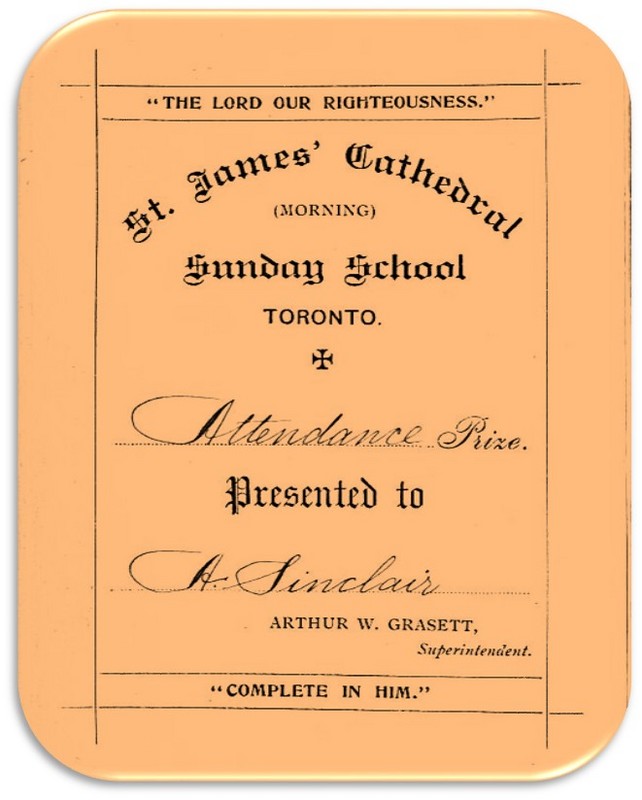

A. Sinclair's Award For Attendance

Implementing "A System of sound universal Education on Christian principles, imbued with a spirit of affectionate loyalty to the Throne and attachment to the unity of the Empire" - H. J. Grasett

UVic's copy of The Cannibal Islands is in nearly pristine condition. There is a bit of wear on the corners of the cover, which seems to be usual wear from being tightly packed into a bookcase for approximately 120 years. There is a slight tear on page twenty-four and the cloth on the cover has bubbled in one spot, perhaps due to moisture; otherwise, the book is perfectly preserved. However, it is not without signs of ownership. The blank pages at the beginning have discoloured around rectangular shapes, as though someone kept photographs or postcards hidden within. The book falls open naturally from to the ninth chapter, “Touches on Cannibalism,” and the pages here have separated from the previous chapter and the spine, which suggests the bloodiest chapter was referenced more frequently than the rest of the book. Furthermore, a bookplate adorned with the words “The Lord Our Righteousness” on the inside cover shows that this book was a prize for a young person at Toronto's St. James' Cathedral Sunday School. According to Journal of Education, Province of Ontario in 1876, the books in the Ballantyne's Miscellany collection were suitable “Books for School Libraries and Prizes” (“Books”). The gender neutral name A. Sinclair[1] is inscribed in flowing handwriting on the “Presented to” line, the same handwriting that indicates that the award is one for “Attendance”; the handwriting belonged to “A.W. Grasett, Superintendent.”[2] Some digging into the church's history and this man's past reveals interesting details. Arthur Wanton Grasett, born 1853[3], was the youngest son of Henry James Grasett, who was the first Rector and Dean of St. James' Cathedral (Mallett). H.J. Grasett was also heavily committed to improving education standards in Canada; the Dictionary of Canadian Biography notes that he sat on the Board of Education for Upper Canada from 1846-1875, under which the establishment of a regulated school system flourished (Turner). His biographer remarks, “Throughout, Grasett said, 'it has been our aim to devise and develop a System of sound universal Education on Christian principles, imbued with a spirit of affectionate loyalty to the Throne and attachment to the unity of the Empire'” (Turner). Arthur's own son, Arthur Edward Grasett, would become a highly decorated military officer, who commanded troops in both World Wars and worked for the British army until his retirement (Palmer). The fact that the men of this family were involved in leadership roles in both the military and the church is intriguing; leadership, missionary work, and a military mentality are some of the main themes of Ballantyne's book. Therefore, although it seems inappropriate subject matter to the modern reader, for A. W. Grasett, a book detailing the civilizing effects of the British and Christian influences in the “heathen” South Pacific must have seemed a logical choice for a child at Sunday School.

[1]I emailed Nancy Mallett, the Archivist and Museum Curator for The Cathedral Church of St. James. She wrote “I cannot find the name A. Sinclair. The Sunday School was very large and in 1879 [for example] it enrolled 1,311 children, 'being the largest Sunday School in the Dominion.'” She was able to verify that both boys and girls attended the school, so A. Sinclair could have been either (Mallett).

[2]Interestingly, Mallett was unable to find any reference to A. W. Grasett being a Superintendent at the church, and has asked me to scan her a copy of the bookplate for their records. On his daughter's baptism record, his occupation is listed as “Gentleman” (Mallett).

[3]Mallett found records that show that A. W. Grasett died March 16, 1934, which of course means that the book could not have been published after this date (Mallett).

Official portrait of Captain James Cook

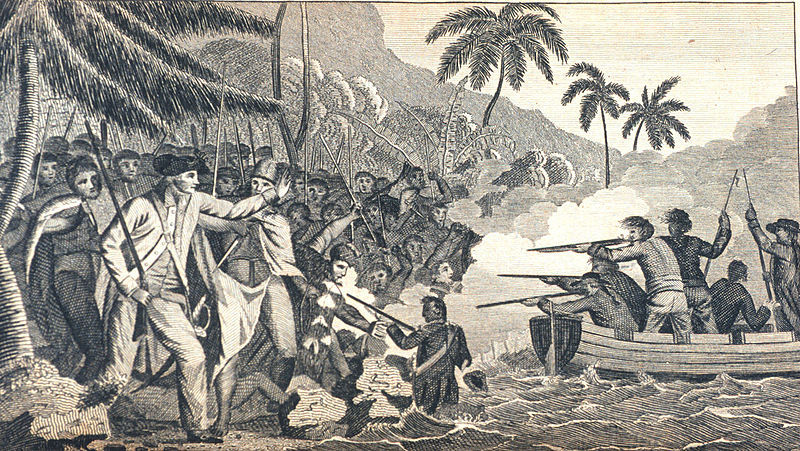

The Death of Captain James Cook at Kealakekua Bay, Hawaii (1790)

Captain James Cook in Polynesia

"'Cannibal Islands' some of them still are, without doubt, but a large proportion of them have been saved from heathen darkness by the light of God's Truth" - R. M. Ballantyne

The Cannibal Islands' introduction begins by enigmatically declaring that “Truth is stranger than fiction, but fiction is a valuable assistant in the development of truth. Both, therefore, shall be included in these volumes” (Ballantyne vii), thereby allowing Ballantyne the freedom to sensationalize certain aspects of Polynesian life. His narrative blends historical fact with genres like romantic adventure, travel writing, and a scientific encyclopedic style to produce what can be classified as creative non-fiction. In “Of Queens and Cannibals: Visions of Leadership in R. M. Ballantyne's Pacific Works,” Jennifer Fuller calls the book “a retelling that transforms the Captain Cook story into a poetic and dashing quasi-biography, with Cook himself a “hero” whose journeys offer life lessons to the young sons of empire” (70). She notes that the emphasis placed on violent native warfare and cannibalism, which in fact appear only rarely in Cook's journals, makes the text more exciting to readers familiar with adventure fiction (71). Indeed, even the chapters illuminating daily island life take fictional liberties intended to grip the reader; in his description of a fruit central to the islanders' diet, the author remarks that it is “about the size of a child's head” (Ballantyne 69). Ballantyne employs a third-person omniscient point of view to follow Cook and the various naturalists and scientists on his team, and he often uses a direct address to speak to the reader. The narrative begins with a description of Cook's humble beginnings in England, establishing what a fine example of British manhood the captain was. This tone of British infallibility builds over the next few chapters, as Ballantyne describes the marvellous advances in technology and science which he eventually champions over the natives' own simplistic technologies. One such chapter describes a naturalist “seeking new sorts of plants which no botanists had ever heard of. . . exploring a country that has never been trodden by the foot of a civilized man since the world began” (Ballantyne 25), thereby marginalizing the considerable knowledge the natives possessed about their own lands. In “The Representation of the Cannibal in Ballantyne's 'The Coral Island'” Martine Hennard Dutheil observes,

the customs, rituals, and religious beliefs of the islanders are accordingly presented as objective, empirical facts. But the self-proclaimed authority of the narrative becomes suspect as it blurs the boundary between imaginative literature and ethnographic document. The representation of the savage thus becomes symptomatic of the interested confusions taking place in the production of 'scientific knowledge' in Victorian texts. (109)

Any news that came to Britain from Polynesia was considered factual; as Patrick Brantlinger notes in his book Dark Vanishings, “Much of what Ballantyne had to say about “the savages” is taken directly from missionary sources,” and further explains that “the evangelical missionaries of the 1790s and early 1800s interpreted savage customs as sins or, at any rate, as the outcomes of sin and superstition” (145, 142). Thus Ballantyne, with an eye towards representing “true facts, truthful impressions” (Ballantyne vii), relies on texts like the missionary William Ellis' prejudiced amateur ethnography of Polynesians, Polynesian Researches, to inform books that he would market to the young men of the British empire like A. Sinclair, this book's church-going recipient.

Ballantyne spends the first eight chapters of The Cannibal Islands detailing British superiority over the islanders; in chapter nine he finally delivers his title's promise of barbaric gore. He writes, “Some of our readers may, perhaps, think we might have passed over the sickening details in silence, but we feel strongly that it is better that truth should be known than that the feelings of the sensitive should be spared” (81). He references Ellis and embarks on an elaborate description of Polynesian cannibalism and treatment of the dead, eventually arriving at the chapter's concluding scene: “Without going further into the disgusting details, it may be sufficient to add that the three bodies were cut up by the priest and cooked in an oven heated by means of hot stones, after which they were devoured as a great treat, and with infinite relish, by the king and his chief men” (88). The reader is left to wonder what “further disgusting details” the author has omitted. Brantlinger writes

Ballantyne echoes the trope of “unspeakable” horror that ran through missionary discourse before it became endlessly recycled in imperialist fiction, from The Coral Island down to Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness (1899) and beyond. Given the graphic accounts of savage warfare, cannibalism, torture of captives, infanticide, strangling of widows, burial alive of the infirm and aged, and treacherous murder of political rivals both in Ballantyne and in missionary journals and letters, one wonders what exactly remained “unspeakable”? (148)

While there is some mention of cannibalism in Cook's journals, there is certainly not enough description to warrant the chapter-long bloodbath that Ballantyne sees fit to describe (Fuller 71). The depictions of debauched cannibalism fascinate and ultimately serve Ballantyne's purpose of proving the admirable transformative influence of the Christian missionaries. In his closing statement, Ballantyne exclaims, “'Cannibal Islands' some of them still are, without doubt, but a large proportion of them have been saved from heathen darkness by the light of God's Truth as revealed in the Holy Bible, and many thousands of islanders. . . are now, through God's mercy, clothed and in their right mind” (120). Overall, Ballantyne's use of gory detail facilitates the “othering” of Polynesian society, establishing British culture and morality as superior and illustrating the civilizing effects of Christian influence. This book effectively sensationalizes the most morbid details of Cook's journals and Ellis' missionary texts to entice young male readers, in order to impart a heavy dose of Christian morals and stoke British imperial pride.

Roughly one hundred years ago, A. Sinclair (who could have been a girl, but was likely a boy given Ballantyne's usual audience) received his copy of The Cannibal Islands for his exemplary attendance at St. James' Cathedral Sunday School. We might therefore speculate that his family was devout, perhaps even rigidly so; it stands to reason that the book in UVIC's Special Collections was extremely well preserved because Sinclair's parents considered it inappropriately bloody for a young boy and kept it from him. Alternatively, he may have hidden the book from them; the rectangular shadows of old pictures or postcards may indicate that the book was a secret hiding place for precious tidbits, and the excellent condition proof that he treasured it dearly. However, it may be that A. Sinclair was purely uninterested in what was written between the crimson covers of the little book, thus ensuring its preservation for a time. Certainly, this could not have been said of the Victorian public, who relished the glorified, “inconceivably horrible and disgusting” (Ballantyne 81) tales from Polynesia, which strangely bolstered a feeling of national pride; as Dutheil remarks, “the function of the cannibal is to nurture belief in British racial, cultural, and moral superiority” (106). The grotesque horrors of the Polynesian isles may seem a curious platform for these ideals, but the author knew the tastes of his audience well. Quayle states, “Ballantyne gave them all the action they desired, making blood stream down the pages of his books, but not forgetting to slip in a sermon or two” (Ballantyne the Brave, 130-1). Just as Captain Cook was “anxious to do as little harm as possible” when he opened fire on the native islanders “to establish his superiority” (Ballantyne 49), so too was Ballantyne anxious that his book should be both exciting and morally instructive when he chose to bombard his readers with embellished atrocities, perpetuating dangerous cultural stereotypes to the God-fearing boys of the mighty British empire.

Works Cited

Ballantyne, Robert Michael. The Cannibal Islands, or, Captain Cook's Adventures in the South Seas. London: James Nisbet & Co. 1-120. Print.

"Board and Residence, 7, Montague-street,." Times: London, England. 10 Jan. 1870: 12. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 25 Mar. 2015.

"Books For School Libraries and Prizes." Journal of Education, Province of Ontario.1 Dec. 1876. Empire. Web. 20 Mar. 2015.

Bissell, Mary. "Re: Cannibal Islands 1898." Message to Renee Gaudet. 27 Mar. 2015. E-mail.

Brantlinger, Patrick. Dark Vanishings: Discourse on the Extinction of Primitive Races, 1800-1930. Ithaca and London: Cornell UP, 2003. 1-248. Print.

Chadwick, Edward Marion. "Ontarian Families: Geneologies of United-empire-loyalists and Other Pioneers...(Volume 2)." Mocavo. Rolph. Smith & Co., 11 Feb. 2012. Web. 15 Mar. 2015.

Dutheil, Martine Hennard. "The Representation of the Cannibal in Ballantyne's 'The Coral Island.' Colonial Anxieties in Victorian Popular Fiction." College Literature Vol. 28.No. 1 (2001): 10522. JSTOR. Web. 23 Feb. 2015.

Ellis, William. Polynesian Researches, during a Residence of Nearly Eight Years in the Society and Sandwich Islands. 1st ed. Vol. 1. New York: J. & J. Harper, 1833. Print.

Fuller, Jennifer. "Of Queens and Cannibals: Visions of Leadership in R. M. Ballantyne's Pacific Works." Victorians Institute Journal. 41 (2013): 63-85. Print.

Gascoigne, Bamber. How to Identify Prints. 2nd ed. New York: Thames and Hudson Inc., 2004. Print.

"History and Architecture." The Cathedral Church of St. James: Diocese of Toronto, Anglican Church of Canada. Web. 15 Mar. 2015.

Mallett, Nancy. "Re: My Project." Message to Renee Gaudet. 25 Mar. 2015. E-mail.

Palmer, Robert. "A Concise Biography of Lieutenant General Sir Arthur E. GRASETT." British Military History. 6 Feb. 2014. Web. 15 Mar. 2015.

Quayle, Eric. Ballantyne the Brave: A Victorian Writer and His Family. London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1967. 1-316. Print.

Quayle, Eric. R. M. Ballantyne: A Bibliography of First Editions. London: Dawsons of Pall Mall, 1968. 1-128. Print.

Rennie, Neil. ‘Ballantyne, Robert Michael (1825–1894)’. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004. Web. 22 Mar. 2015.

Sadleir, Michael. Sadleir's XIX Century Fiction: A Bibliographical Record Based on His Own Collection. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1951. 22-23. Print.

Turner, H. E. "Grasett, Henry James." Dictionary of Canadian Biography. University of Toronto/Universite Laval, 2003. Web. 15 Mar. 2015.

Wolff, Robert Lee. Nineteenth-century Fiction: A Bibliographical Catalogued Based on the Collection Formed by Robert Lee Wolff. Vol. 1. New York: Garland Pub., 1981. Print.

RG/Fall 2016

![[Untitled] [Untitled]](../../../../files/square_thumbnails/4334535e92f5c699acafd5bf77ceaefa.jpg)

![[Untitled] [Untitled]](../../../../files/square_thumbnails/e4a8f142cdf797d4a48bd0f56927a611.jpg)

![[Untitled] [Untitled]](../../../../files/fullsize/11ccc228375784fa47d5467dbb88ef33.jpg)