Emily Carr's Hundreds and Thousands

Source Material

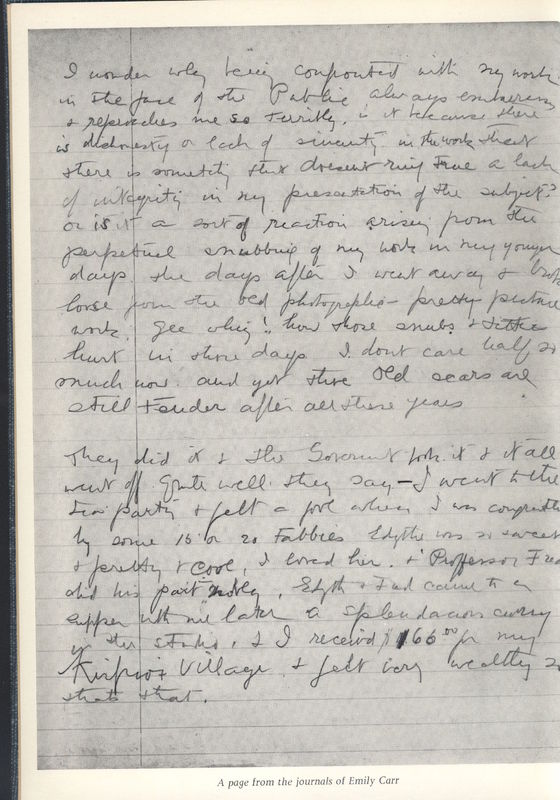

"Wherever she went, she took along a notebook and pencil with which to capture the mood and artistic beauty of a scene before she began to sketch it."

"All of this material formed part of the journals she kept faithfully."

This is the first publication of Emily Carr’s journals, which she began writing in 1927. Through these journals, we are given an account of her life up until 1941. Carr documents her experience as an artist, as a writer, and her connection with nature. Although we can now recognize Emily Carr as a Canadian icon, these journals present her as a self conscious individual that was struggling with honing her craft, and her place in the world as a First Nations person.

Despite devoting many years of her life to writing in her journal, the publication of these journals is significant because it is posthumous. By the time her journals were published in 1966, Emily Carr was already a Canadian icon.

In this limited edition publication of Emily Carr’s journals, Carr is presented as a Canadian legacy. Much respect was given to her rememberance.

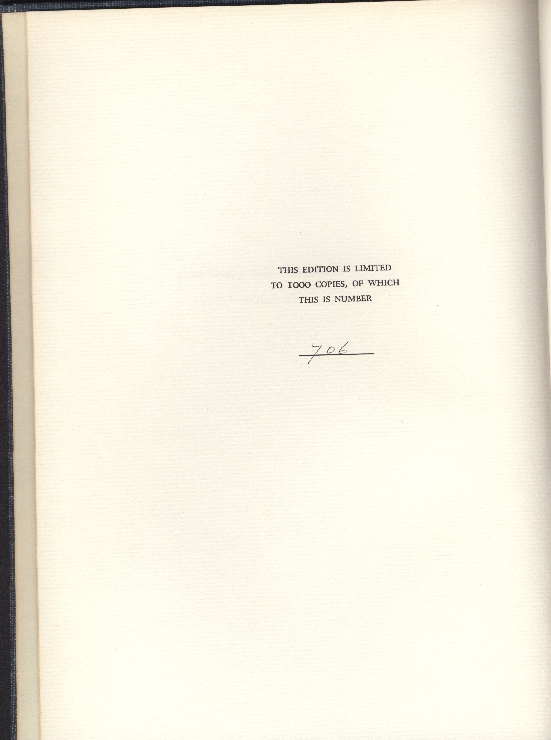

There are only 1000 of these limited edition copies circulating, which makes this book a collectors item. Scholars of book collecting have indicated that publishing in limited edition format indicates a desire to preserve the item. Specifically, John Carter states: "the publisher considers that the book will sell better if a scarcity value is created from the start; the publisher estimates that the potential sale of the book is x hundred (or thousand) copies, and decides, when printing so many and no more, to make a virtue of necessity by adding a formal limitation notice" (143). This holds true for Emily Carr's book because the publishers of this particular book cleary wanted Emily Carr's painting and writing to be preserved.

Special Collections of the University of Victoria currently owns two of them: this particular copy (numbered 706) and one other (numbered 99).

The text indicates multiple times that this final product is drawn from a collection of Emily Carr's hand written journals. The limited edition makes this clear by including a fascimilie of the journals. This is something that makes the limited edition unique.

Emily Carr was aware that her handwriting was not good. In one of her letters to Ira Dilworth, Emily Carr stated: "I can't read my own writing" (Morra 1). Readers are not given a page number leading to the editorial interpretation of her handwriting.

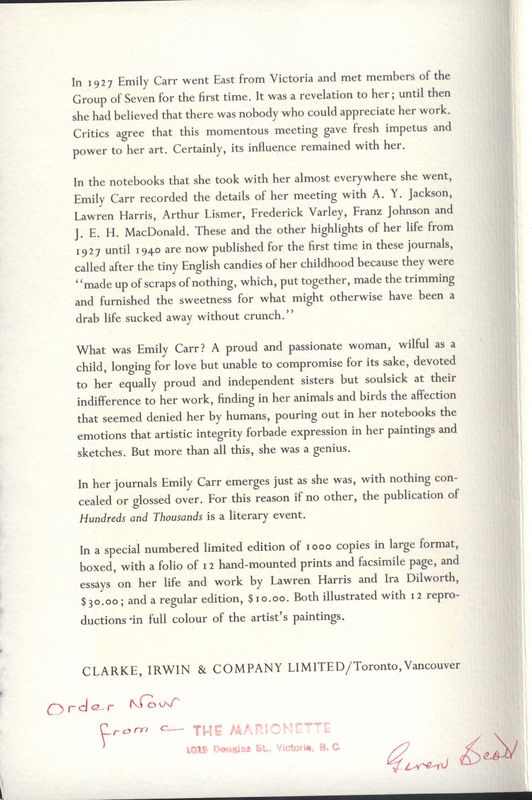

Advertisement for limited edition

This limited edition first publication of Emily Carr's journals is available with a pamphet which can be viewed as paratext to the book. In their introduction to Paratext, Genette, Gérard, and Marie Maclean state: “One does not always know if one should consider that they belong to the text or not, but in any case they surround it and prolong it, precisely in order to present it” (261). Without the pamphlet, many readers may not be fully aware of the woman behind the journals. Indeed, the text does ask: "What was Emily Carr?". This positions Emily Carr as more of an entity than a person. This continues in the line: "she was a genius". Such statements indicate that this advertisement is also catered to people who are unfamiliar with Emily Carr’s work. Additionally, this pamphlet identifies Emily Carr as a commodified person. It advertises regular copies of the journals for $10.00 and limited editions for $30.00

Ultimately, the pamphlet announces the publication of Emily Carr's journals as a literary event, which means that readers are meant to pay attention to aspects of publication.

The pamphlet introduces Emily Carr in relation to two people who were personally familiar with Emily Carr: Ira Dilworth and Lawren Harris. This limited edition includes essays on her life and work by them.

Ira Dilworth

Ira Dilworth was responsible for transcribing Emily Carr’s writing. He is remembered for serving the arts in British Columbia, and for working as an administrator for the CBC.

He helped her establish her reputation as a writer by broadcasting her stories on CBC Radio. He then negotiated with Oxford University Press in Toronto on Carr’s behalf to publish both Kylee Wyck and Book of Small. (Tippett 256).

Ira Dilworth and Emily Carr were very close friends also, especially in the time frame that these journals were written. Within the span of 5 years, Carr and Dilworth wrote to each other almost every day. These letters reveal the intensity of their friendship. On August 31 1941 Ira Dilworth wrote to Emily Carr stating: "Our friendship is one of those great things in life which seem too great and wonderful to be true. I keep expecting to wake up and find that I have been dreaming"(Morra 3). He wrote this before he began to edit her manuscripts and influence her writing career, which strengthened their relationship in both a professional and personal way.

Once their relationship developed, Emily Carr felt confident to ask Dilworth to take charge of her short story collection entitled "The Book of Small". Dilworth was delighted with the offer, which lead Carr to designate him "legal guardian of Small" (Morra 13).

After Carr's death, Ira Dilworth was named literary executor of her writing. He edited and arranged publication for her remaining texts, including Pause: A Sketchbook, a memoir of the time Carr spent in an English sanatorium; House of All Sorts, recollections of her colourful tenants at Hill House; and Growing Pains, her autobiography.

Lawren Harris

When I returned from the East in 1927, Lawren Harris and I exchanged a few letters about work. They were the first real exchanges of thought in regard to work I had ever experienced. He helped wonderfully. He made many things clear, and the unaccustomed putting down of my own thoughts in black and white helped me to clarify them and to find out my own aims and beliefs

(Hundreds and Thousands, pp. 20-21).

Ah, little book, I owe you an apology. I've got to like you despite how silly you seemed to me when Lawren suggested I start you. You help me sort and formulate thoughts and you amuse me, which is more than housecleaning does, and that is what I have been doing for the week

(Hundreds and Thousands, p. 102)

An influential person for Emily Carr's paintings was Lawren Harris. He was a member of the Group of Seven. It is believed that her connection with the Group of Seven lead to her recognition as a modern artist. Their mission was to "depict the stark landscapes of central Canada's near northern reaches realistically rather than through European based artistic conventions" (Thacke 182).Another source defines them as “the eastern Canadian painters who from 1911 developed images of wilderness landscape that were seen as the expression of a modern Canadian national identity” (Gaze 351). Emily Carr met the Group of Seven in 1927 while exhibiting her work in the exhibition West Coast Art: Native and Modern. In a discussion on the discovery of Emily Carr, Maria Tippett states: "Travelling East for the opening of the exhibition she met the Group of Seven and established a long relationship with one of its members - Lawren Harris. Revived in spirit through contact with the Group she returned West, picked up her long-idle brushes, and began the most intense and prolific period of her career" (30).

Lawren Harris told Carr, who had felt unappreciated as an artist, "you are one of us." This acceptance re-energized her career.

In relation to the Group of Seven in general, Ian M. Thom states: "The Group of Seven's approach to the Canadian landscape resonated with Carr and helped her focus on her own spiritual and visual journey. Immediately upon her return to British Columbia, Carr began painting again" (9).

This collection of journals begins with an entry entitled "Group of Seven".

Authorial Intervention

The preface to "Hundreds and Thousands" is effective at the beginning of the text because it indicates that Emily Carr was anticipating for her work to be published. From the outset, she refers to her journals as a "manuscript" which is defined as both a handwritten text or document, and a text that is to be published. She asks:

"Why call this manuscript Hundreds and Thousands?"

"Because it is made up of scrps of nothing which, put togetherm nade the trimming and furnished the sweetness for what might othewise habe been a drag life sucked away without crunch. Hundreds and Thousands are minute candies made in England- round sweetness, alll colours and so small that seperately they are not worth eating."

Unfortunately Emily Carr was not able to finish the project she started because she died in 1945.

Emily Carr left her manuscript to Ira Dilworth. The publishers foreward indicates that transcribing Emily Carr’s journals was no easy task, as it states, “He began the monumental task of transcribing the notebook’s from the artists handwriting”.

Prior to her death, Carr had expressed much of her anxieties about writing to Dilworth in her letters of correspondance. Throughout her writing process, Carr struggled with either being "too formal" in her approach or "too personal". In one of his letters, he stated, "how you hate the idea of "wearing your heart on your sleeve for every daw to pick at" (Morra 17). Inded, at this point in her life, Carr was recognizable as a Canadian figure; therefore, she was aware that her writing would be available for public consumption.

Nevertheless, Carr held immense faith in Ira Dilworth. He calmed her worries. It was Dilworth that introduced Emily Carr's work to W.H. Clarke. While describing Dilworth's encouragement on behalf of Clarke, Linda Morra states: "By March 1941 he was able to persuade Clarke of the merrits of her work. Dilworth's dicussions with Carr subsequently shifted toward such matters as Clarke's decisions regarding the manuscript and galley proofs, and the deliberations involved in the selection of titles that she wand Dilworth had produced" (15).

Seems to me as you were all over it with Clarke and [,] as you told me of the attention [,] I thought them fine & then Clarke could have gone ahead. Help me out on that dedication and when at it tell me what you'd like me to put in Hundreds and Thousands.

(Emily Carr 1944 Corresponding Influence: Selected Leters of Emily Carr and Ira Dilworth,283)

Subsequently, W.H. Clarke's company entitled Clarke Irwin and Company picked up where Ira Dilworth left off. They did have the support of Dilworth’s niece.

The text indicates that Emily Carr left explicit views on the editing of her writing. Of the upmost importance, was her objection to being polished. She did not want to be influenced by critics. She stated, “I do know my mechanics are poor. I realize that when I read good literature, but I know lots of excellently written stuff says nothing.”

In an attempt to remain true to Emily Carr’s wishes, the publishers have kept the sentences as Emily Carr had written them, claiming to always preserve the eccentricities of her style.

Emily Carr's timeline in relation to Hundreds and Thousands

1927- Meeting with the Group of Seven

"Nineteen twenty-seven was Emily Carr's annis mirabilis, the year she was discovered for Canadian art through the National Gallery's Exhibition of Canadian West Coast Indian Art and simultaneously introduced to the stimulating influence of the Group of Seven." (Tippett 30)

Additionally, Emily Carr gained further recognition when she was discovered by Marius Barbeau. This lead him to create a West Coast art exhibition. Twenty six of her pictures were exhibited (Dilworth 15).

1930- First "one woman show"

After returning to Victoria with renewed vigour from her encounter with the Group of Seven, Emily Carr hosted her own art show in Victoria. This marked the gradual recognition of her work (Dillworth 15).

1937- Hospital

"In 1937, Carr suffered her first heart attack, and her activities as a painter were drastically curtailed. No longer able to sketch from her beloved Elephant, she was forced to rent summer houses and cabins, and increasingly, Carr turned her attention to writing, which she had explored since the early 30's" (Thom 11).

1938-39- The Shadow of War

The Second World War broke out, which made Ira Dilworth "sensitive to the general vulnerability of art" (Morra 18). Similarly, Carr was negatively affected by the war as well. In their letters, "He and Carr discussed at length the effects of war, ranging from its direct impact on their lives to their mutual sense of how it was causing havoc internationally, destroying human life and cultural artefacts, and obscuring the best that humanity had to offer"(18).

1940- First letter from Ira Dilworth to Emily Carr"

“I do think your sketches should be published. We had a great many very interesting comments on them. A great many more, I should say, than we have had on any other talks or readings.

I am so glad you are getting your roots down again. Somehow I feel happier when I think of you being up in the old locality”

[February 29, 1940)

Corresponding Influence: Selected Letters of Emily Carr and Ira Dilworth, p. 26

1941- Publication of Klee Wyck

in July 1940, Ira Dilworh got into contact with W. H. Clarke to persuade him of Carr's literary merits, and to discuss the possibility of publishing her literary sketches (Morra 15).

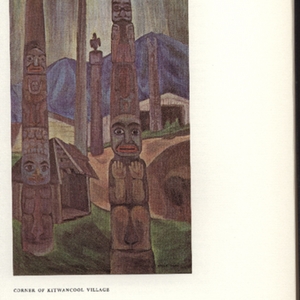

This turned into the publication of her literary sketches entitled Klee Wyck in October 1941. Klee Wyck is an autobiographical text depicting her experience as a First Nations person in British Columbia. This collection was highly acclaimed. She earned a Governer Generals Award for this collection the same year.

1942- Last sketching trip

1943-44- A time for writing

Emily Carr was confined to her bed during this period. This was a time she devoted to her writing. (Dilworth 17).

1944- Publication of "The House of All Sorts"

This text is a collection of stories that reflect on her experience owning an aprtment building which she built in 1913. This was a time before her success when she was trying to make a living

1945- Death of Emily Carr

Emily Carr's legacy as a painter

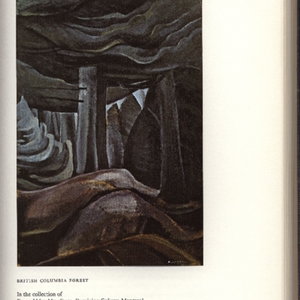

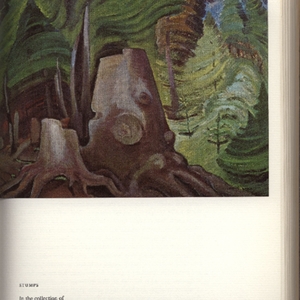

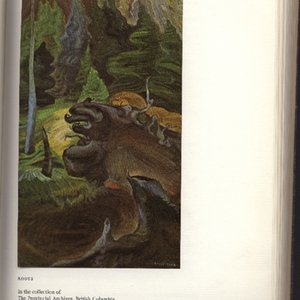

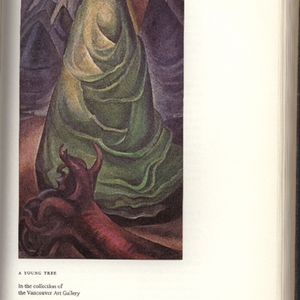

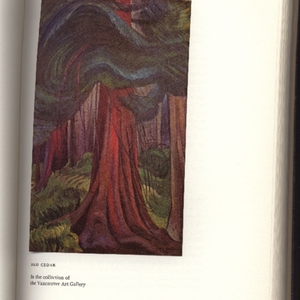

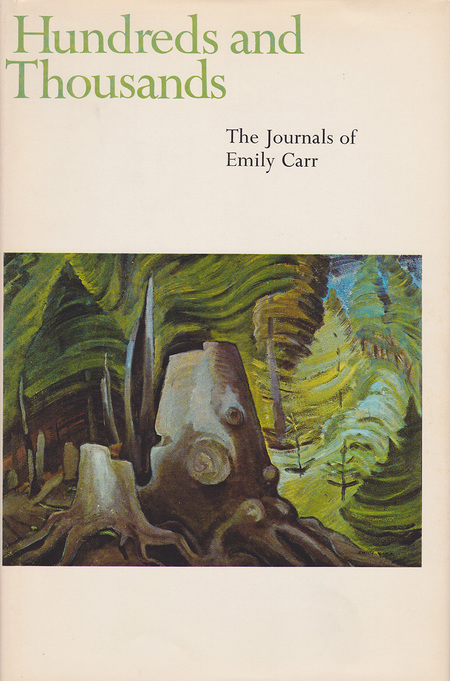

This limited edition of the publication of Emily Carr's journals includes samples of Emily Carr's paintings throughout the text. Indeed, Emily Carr is primarily known as an artist. She is associated with the modernist movement in art. Her primary influence was First Nations people

The paintings are primarily what establishes this edition as unique. They are reproduced from several art collections around Canada and hand mounted on the paper. There is no indication that they correlate at all with the journals.

These paintings are included to credit the art galleries that donated the paintings, which futher explemfies this text as a collaborative project.

Specifically the Vancouver Art Gallery donated the majority of the paintings that are included in this edition. Their website indicates that Carr had planned to hold an exhibit at their gallery prior to her death.

Additionally, the Vancouver Art Gallery has long been a supporter of Emily Carr's work. In 1992, the Vancouver Art Gallery published a booklet as an accompaniment to its art exhibit dedicated to Emily Carr. In this booklet, it is stated: "The Vancouver Art Gallery's collection constitutes the most important group of paintings and drawing's by this artist. Nearly 190 works were given to the Gallery by the artist and her trustees through the Emily Carr Trust" (5).

This booklet also includes a letter from Lawren Harris, in which he states that she wanted her art to be exhibited in the Vancouver Art Gallery, because "Mr. Grigsby, who was then Curator of the Gallery, had permitted her work to be exhibited"(12). He then goes on to say that she found it hard to imagine her art being exhibited anywhere else.

Much like her writing, Emily Carr was not confident in her painting. Lawren Harris states, "On one occaision, as we were looking over her canvases, I asked her what she planned to do with her work- what was to become of all these paintings? She replied, 'Give them to the old folks home. I suppose they would put them in the basement, and there they would rot' (Thom 12).

Smaller 1966 non-limited edition copy of Hundreds and Thousands

2006 publication of "Hundreds and Thousands"

Further Publications

The success of this limited edition is best represented through further publications of the text. Within the Special Collections in University of Victoria, there is another copy available of Hundreds and Thousands that is essentially the same; however, it is smaller (24.5cm x 15.5cm) with a book jacket that includes a frontispiece and a print of one of Emily Carr’s paintings. The back cover of the book jacket includes a picture of Emily Carr in Victoria, and a quote from the preface to Hundreds and Thousands. Additionally, the paintings that are included throughout the journals are printed on the paper in a more secure manner rather than loosely pasted on the page as in the limited edition copy

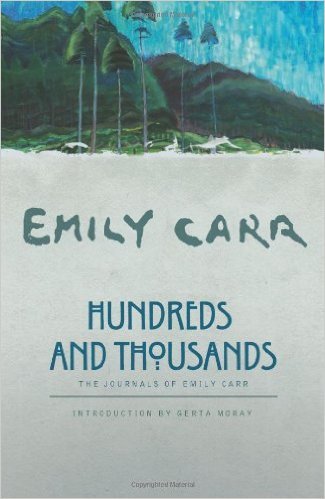

After this first publication of Emily Carr’s journals, another edition was published in 2006 by the publishing company Douglas & McIntye. This edition is clearly meant for mass production. The back cover of the text includes critical acclaim from “Publishers Weekly” and “Robertson Davies.” This edition also places considerable influence on the editor of the text. The back cover states, “Gerta Moray, a noted authority on Carr’s work, provides an informative introduction that sheds light on the person behind the journals.” This indicates that readers are meant to pay attention to the scholarly work done by Gerta in addition to reading the journals. The text also includes a list of the complete works of Emily Carr published by Douglas & McIntye. This presents Emily Carr as a more commercialized person. The text also includes the date at the top of each page, which reflects its scholarly association.

Works Cited

Carr, Emily. Hundreds and Thousands: The Journals of Emily Carr Clarke, Irwin, & Company, 1966.

Carr, Emily. Hundreds and Thousands: The Journals of Emily Carr Ed. Gerta Moray.Douglas & McIntyre, 2006.

Carr, Emily. Klee Wyck, Douglas & McIntyre, 2003.

Carr, Emily, 1871-1945. The House of all Sorts, Oxford University Press, 1944.

Carter, John. ABC for Book Collectors Hart-Davis, 1972.

Dillworth, Ira. Harris, Lawrin. Emily Carr: Her Paintings and Sketches, Oxford University Press, 1945.

Gaze, Delia. Dictionary of Women Artists, Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 1997.

Genette, Gérard, and Marie Maclean. "Introduction to the Paratext." New Literary History, vol. 22, no. 2, 1991., pp. 261-272

Mastai, Judith. “Emily Carr” Vancouver Art Gallery. 1992.

Morra, Linda “Corresponding Influence: Selected Letters of Emily Carr and Ira Dilworth” University of Toronto Press 2006.

M. Thom, Ian. “Emily Carr Collected” Douglas & McIntyre, in association with the Vancouver Art Gallery. 2013.

Tippett, Maria. Emily Carr: A Biography, House of Anansi Press, 2006.

Tippet, Maria. “Who Discovered Emily Carr?” Journal of Canadian Art History vol. 1 no. 2. 1914. pp. 30-34.

Thacker, Robert. "Being on the Northwest Coast: Emily Carr, Cascadian." The Pacific Northwest Quarterly, vol. 90, no. 4, 1999., pp. 182-190.

ES/Fall2016